If you’ve seen it, you haven’t forgotten it: Action Bronson hurtling across the desert on a Harley, high on acid, bare chest adorned with tats that shout anarchy beneath the open military jacket, his face contorted in agony and ecstasy. This psychedelic vision made “Easy Rider” one of the most memorable rap videos in recent history—a credit to the Queens demigod, of course—but also to the director responsible for the mind-bending LSD trip, Tom Gould.

The New York-based photographer and filmmaker has always held a curiosity for outlaw figures. Since finding himself drawn to the furtive shadows of graffiti as a teenager in his hometown of Auckland, NZ, Gould has been pulled into the orbit of clandestine figures. He seeks them out, fully explores their character, and finally dimensionalizes the story on film.

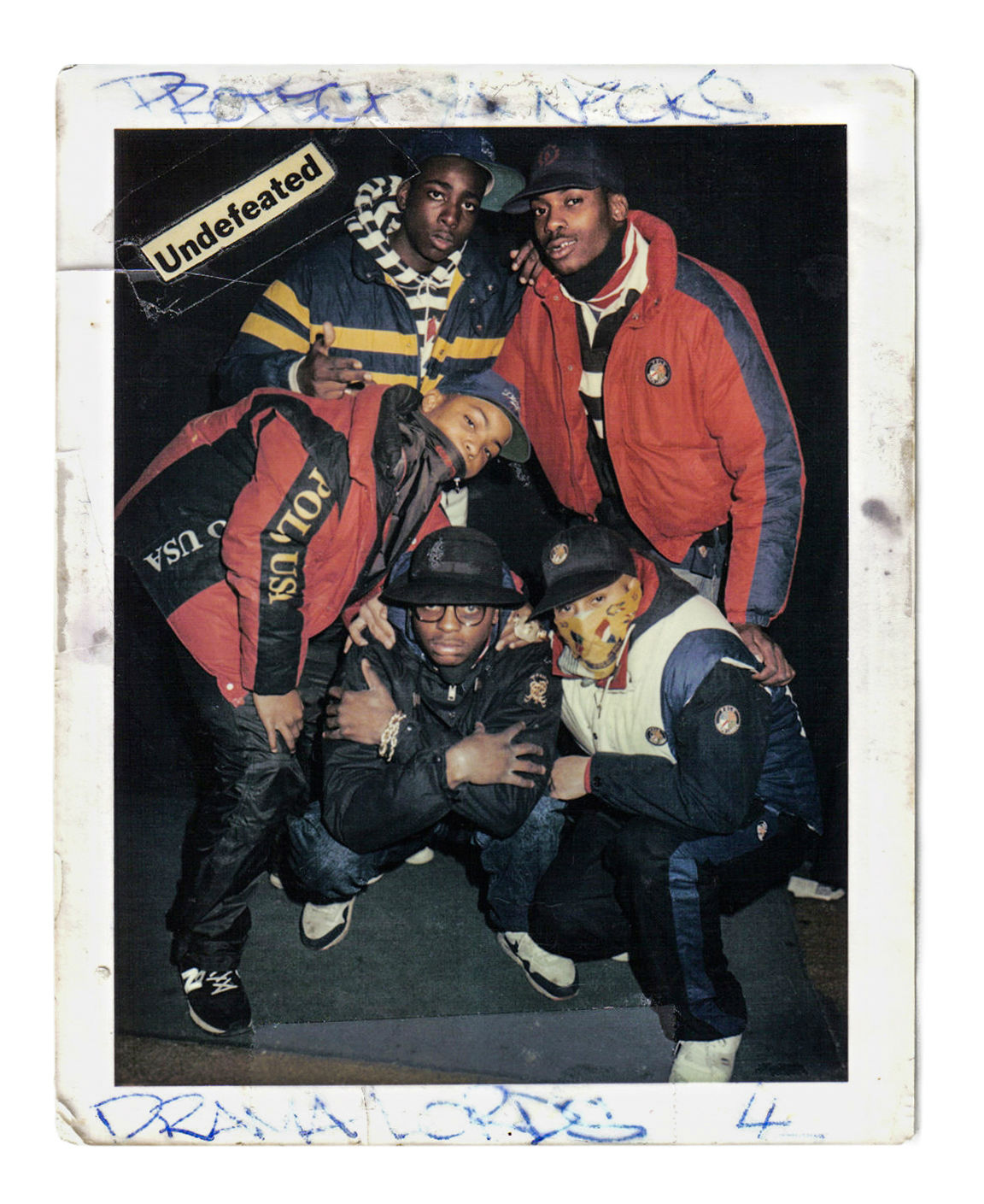

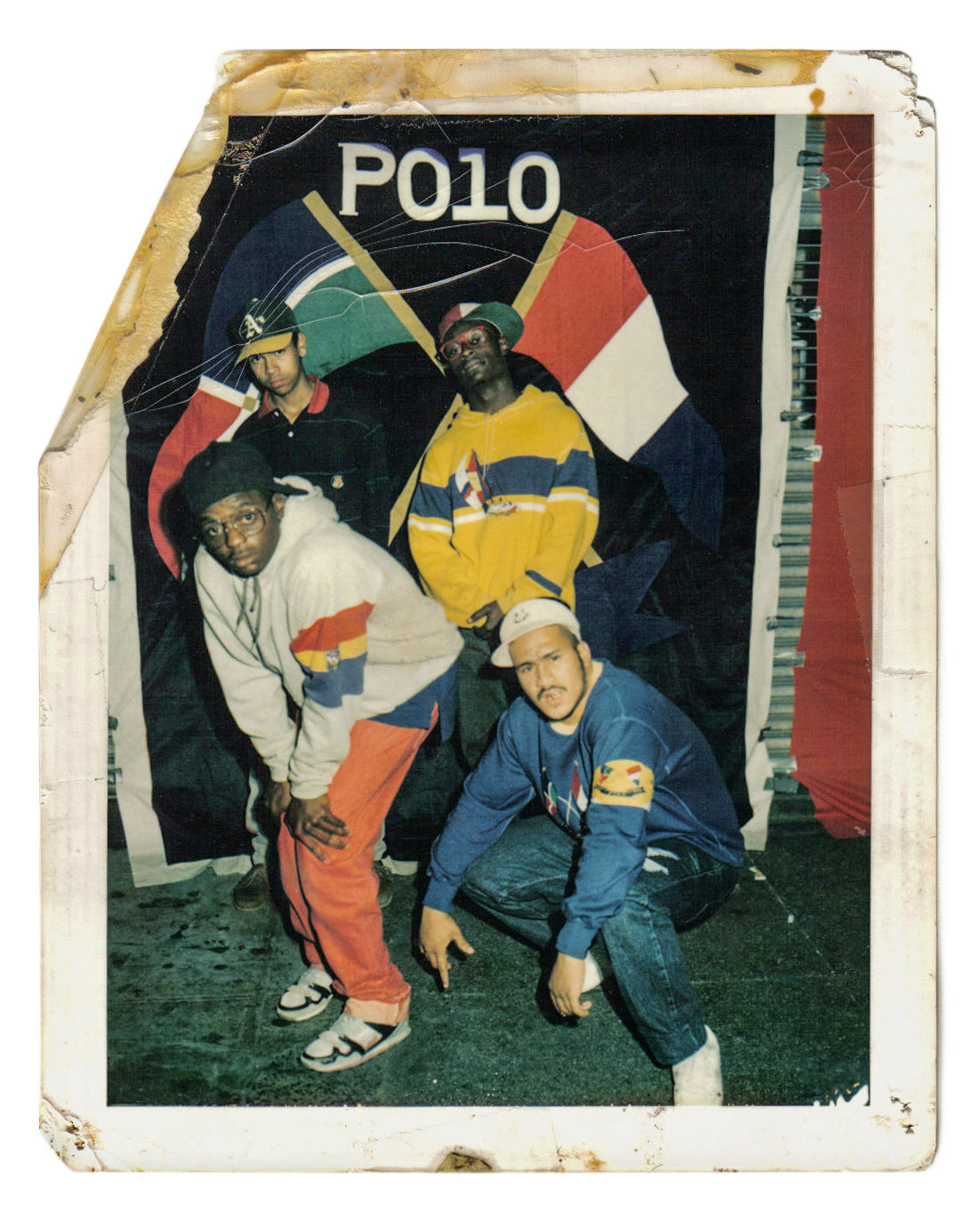

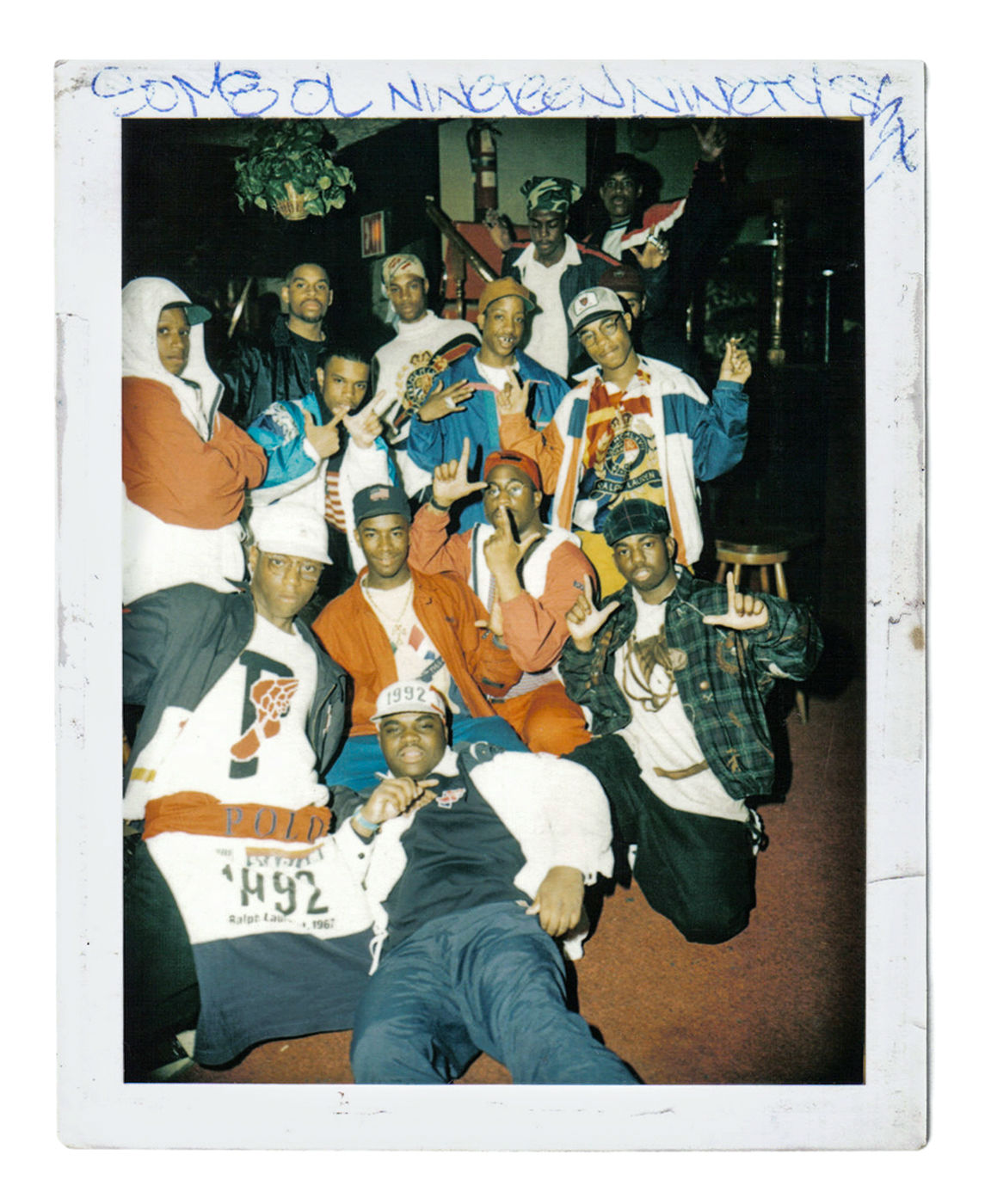

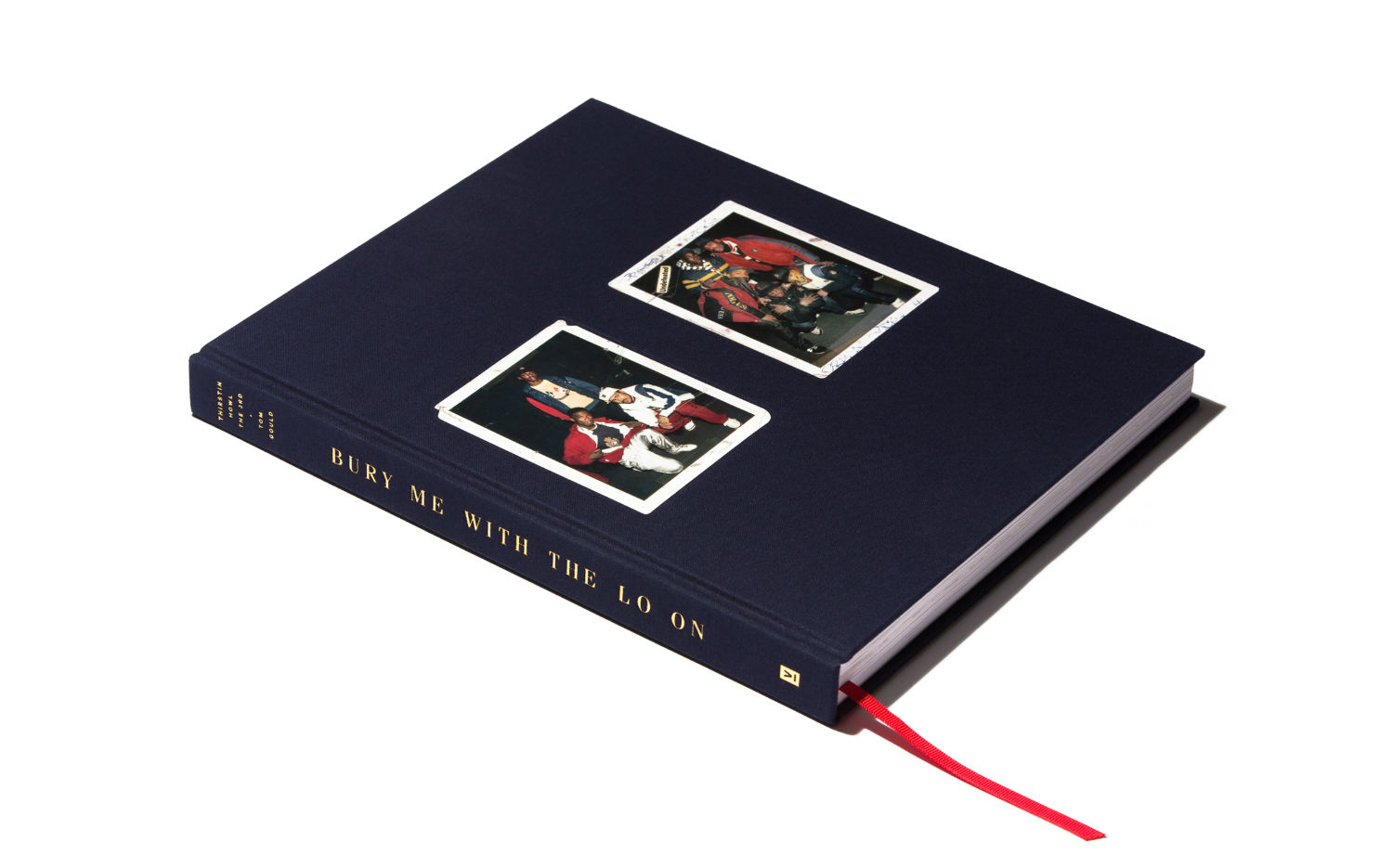

Gould continues to explore often misunderstood individuals in his latest project, Bury Me With The Lo On. The exquisite 264-page book documents a curious subculture that can be traced back to late-’80’s Brooklyn and the formation of a gang known as Lo Lifes. Perceived by some as thugs and by others as heroes, these teenagers aspired to a life the world presumed was beyond their reach and took something that wasn’t meant for them, Polo Ralph Lauren, and made it their own.

Co-authored alongside Lo Life founder Thirstin Howl the 3rd and published by Victory Editions, Bury Me With The Lo On has been meticulously assembled by the pair over the past five years. They carefully unfold the many layers to the Lo Lifes story, with oral histories from key members and never-seen-before archival imagery alongside new portraits.

Grotesk sat with Gould to learn how a young kid from New Zealand ended piecing together the first-ever comprehensive history of Lo Lifes and the subculture they inspired. —Marisa Aveling

Grotesk: Could you explain what this subculture and movement is about and when it started?

Tom Gould: The Lo Lifes were a group of teenagers from neighboring areas of Brooklyn who came together in 1988 to form a boosting (shoplifting) crew with the common goal of accumulating as much Polo Ralph Lauren as possible, by any means possible. The word Lo was taken from the second syllable of Polo. When people think of gangs, they normally associate the fashion to be flashes of red or blue, or leather motorcycle club patches, but what made Lo Lifes different was that they dressed in the finest garments stolen from every upper-class department store in the tri-state area, while living a reality that was the complete opposite of what Ralph Lauren represented. Over the past 30 years, the stories of the Lo Lifes and this particular fashion has spread throughout the world, birthing a subculture of collectors of vintage Ralph Lauren garments.

Growing up on the other side of the world, how did you first hear about the Lo Lifes?

We were pretty isolated from the rest of the world and what was going on within hip-hop in New York, but that just made us more intrigued and eager to see more, and that made it special. We were always paying close attention to the fashion coming out in the latest music videos and album covers and, of course, trying to get our hands on the newest music coming out of the States.

A couple of the older graffiti crews in Auckland were wearing Ralph Lauren in the late ’90s, and as a younger kid coming up, I was influenced by their style and loved the look of Polo.

Around 2001, the tales of the Lo Lifes had spread to Auckland, as Thirstin Howl the 3rd’s album, Skillionaire, was out. After hearing stories about them from the older crews and then listening to the music, it all made sense. Once I started seeing images of Lo Lifes appearing in magazines and on the internet, my fascination grew.

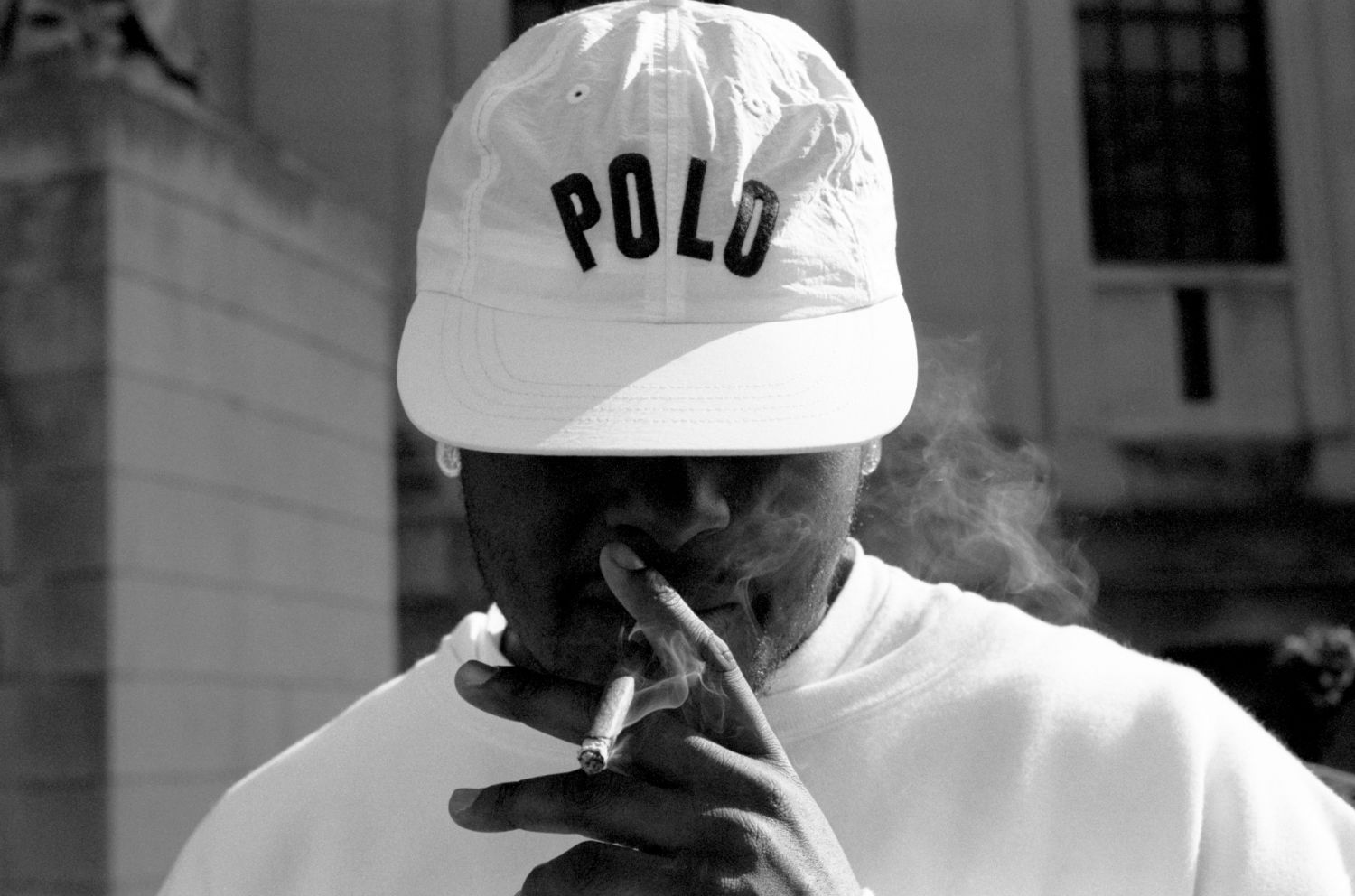

Lo Goose on the Deuce, 42nd Street, Times Square, 2012

Tell me about the title.

Bury Me With The Lo On was originally the name of a song by Thirstin Howl the 3rd from Skillionaire. The song talked about the desire of being buried wearing Polo Ralph Lauren. Sadly, for many Lo Lifes, this was a reality. Many members of the gang were killed or passed away over the years and were buried wearing their favorite Polo outfits along with pictures of themselves and their crew sporting various Polo patches and insignia. The title is a way of respecting those who passed and to shed light on the extent that people went to for this brand. It really meant a lot to people and signified something greater than just clothing.

When did Lo Lifes transition from a New York gang into a fashion movement?

The notoriety of Lo Lifes started in Brooklyn and quickly spread throughout New York via word of mouth, articles in the newspapers, and then by rappers like Jay Z mentioning them in his lyrics. The culture spread to Philadelphia around 1991 through the travels of Lo Life members, and it carried on from there.

Rappers like Grand Puba and Raekwon were wearing Polo in music videos around this time also, which popularized Ralph Lauren within the hip-hop community on an international level. People from all over the world wanted to get their hands on these items of clothing.

Once the music of Thirstin Howl the 3rd came out in 1999 and the tales of the Lo Lifes were immortalized in his songs, people realized the stories that were behind this fashion and it created the beginnings of a worldwide subculture. This culture has only grown as images of Lo Lifes from the late ’80s and ’90s have emerged over the years, showing them dressed head-to-toe in these rare and expensive Ralph Lauren garments. Made in the late ’80s throughout the 1990’s, they have become collectors’ items and highly sought after by people as far away as Japan.

I love how you always seem to gravitate toward obscure subcultures, outlaws and somewhat inaccessible groups of people. Any specific reason why you’re attracted to them?

I think I have been attracted to subcultures and niche subjects because I was involved in them growing up. I was big into graffiti as a teenager and loved the allure of being part of something that was only meant for the other people who understood and appreciated it. That same mentality resonates with a lot of the subjects that I’ve documented and allows me to connect with them. Now, as a photographer and filmmaker, I enjoy exploring these kinds of people and subcultures and opening other people’s eyes to them, showing the beauty in even the heaviest of subjects.

I have always been interested in gang culture. Despite New Zealand’s reputation of being a clean, green country, it has some of the largest numbers of motorcycle gangs and patched street gangs. A lot of these gang members have committed heinous crimes and have a very negative reputation in the media. I made a film called Skin about a member of New Zealand’s largest gang, the Mighty Mongrel Mob, where I aimed to show a more human side of them, one that wasn’t portrayed in the media. Skin himself was a gang member, but also a champion racecar driver and a single father who raised ten beautiful children through welfare and foster care.

This subject matter related to the Lo Life story and made me want to document it. Yes, they were thieves and would steal every piece of Polo from Saks Fifth Avenue, but underneath there was an aspiration to be something greater. They empowered themselves by taking something that wasn’t meant for them and making it their own. They dressed in these high-fashion garments but, in all reality, lived in the projects, in Brownsville and Crown Heights, some of the wildest and poorest neighborhoods of New York. Along with all of the drama, there was also a kind of beauty in that.