There's a distinct ping-pong game in your head when you view the work of Sacha Ingber. Initially, you think you know what you're looking at, but immediately, the ambiguity and impracticality of the composition demands an opposite response, challenging the notion of what you presume. This encounter of the familiar and unknown makes Ingber’s sculptural and cast works make a lasting impression that's hard to shake.

The works read as paintings, flat in some cases, hung on the wall in others, yet they achieve a permanent dimensionality akin to architecture or design. Employing various materials such as ceramics, metal, textile, resin and plastics, Ingber’s pieces contrast various textures and surfaces that provoke a different look at the world around us. Some appearing as tableaus, others as crests; but whatever the interpretation, a minute of pause, contemplation and subsequent emotive sensation are Ingber's target.

Sculpting and designing in a unique, problem-solving kind of way, her casts are a landscape of memories, carefully composed with indistinct imagery, symbols, and objects that oscillate with emotional weight. There's a real ah-a moment when you realize that the five foot work in front of you is really an oversized bread clip, something you might handle and use for years but never ruminate on. Through the ordinary and everyday, Ingber is able to weave motifs into a larger conversation, one about the sentimality of objects, how we interact with our surroundings and the ever-so-thin line that separates psychological from physical space. I was lucky enough to sit down with her this past fall to learn more about her motivation and why physicality is inextricably linked to experience, both in her work and in life. Take a look below.

Jessica Ross: You’ve utilized imagery that the average person wouldn't take a second glance at, whether air fresheners, bread clips or towel racks. What about these ordinary objects invites special consideration?

Sacha Ingber: The images that appear in my works often are mundane, but the ones I choose usually echo some sort of memory or personal story. The mundane can be a great starting point. There's something non-presumptive that allows me to throw more meaning at it. For example, the air freshener motif came into my work one day when I was sitting in the back of a taxi. The way this object was dangling, but also blocking the rearview mirror, just stuck in my mind.

I also tend to choose objects that can exist as multiple things in multiple spaces at once; the air freshener can become an actual tree in the work, and I can manipulate it. This sets off a chain reaction of formal play. The particular scent of air freshener I looked at is called “Royal Pine.” I liked how grandiose this name is for such a cheap mass-produced object. In my piece, I turned the air freshener shape into palm leaves and titled the work, Royal Palm. There’s room for wordplay since I changed the reference from a cold climate to warm. The images and objects I like to work with always provide this kind of multifacetedness.

What percentage of your work utilizes found objects? Are they sought out specifically or discovered by happenstance?

Readymades make up a very small percentage of my work. When I do use them, I specifically source them based on the needs of a particular piece. The found objects I use depend on what kind of specificity I’m looking for. Much of the time, I aim for something that appears familiar but is not quite placeable. Other times, I need a real found object to ground the work in reality or scale. By merging the two (readymade and made), I’m trying to pin down the meeting point between real space and psychological space. Using a found object gives me the highest visual resolution of a real thing in the world.

What are some of your earliest memories of sculpting or creating? Are there any objects or tangible things that were seared into your brain as a child? For example, I loved my dad’s shoe-horn. It was smooth and odd, and made no sense to me–yet I adored it.

When I was younger, my mother used to teach ceramics classes in the basement of our house, so I was always observing and doing that. She also once made a mosaic on the bathroom floor by breaking plates we had at home and piecing those together. I also loved sand art. More often than making things, I used to invent my own songs and dances. Many objects I remember being obsessed with as a child were kitchen tools. I was specifically fascinated by this purple ice cream scoop, a flour sifter with trigger action, and a steamer basket. My dad still has all of those in his kitchen today. I also loved those shoe-measuring devices they have at department stores and the beam scales at the doctor’s office.

The visual language in your work is often humorous, sexy, empathetic and political, all at once. How does this happen? Where would you say your work is at right now, conceptually speaking?

Thanks! What a nice grouping of words to see together. I feel that, recently, my work has become more personal than ever, especially the body of work that I am making right now. It might be surprising to hear this, given the playful reading of the work, but I feel that what I’m working on right now has much more to do with my senses, emotion, and freedom, whereas the work I made during the earlier part of my career felt much more rigid. To me, those works were prescribing to very strict rules I would set about an external idea that I would have. What I am working on now is coming from a more internal place. The work is always changing. The thing that never changes is the fact that it’s coming from my brain and my hands. Those themes you mention make their way in and out of the work often and in different combinations. I think, because I’ve always been so interested in multiplicity, I welcome my work being more than one thing at once, the same way that I think a lot about the work reading as images and object all at once. To me, any kind of creative thing – whether it’s music, film, architecture or writing – is the most interesting when it’s complex, falls across genres, or succeeds in making many ideas work together successfully. I really gravitate towards works of art that can reflect the multifacetedness of a real person.

Process is clearly a huge part of your work. Without revealing too much, what are some of your most unexpected favorite parts of your practice?

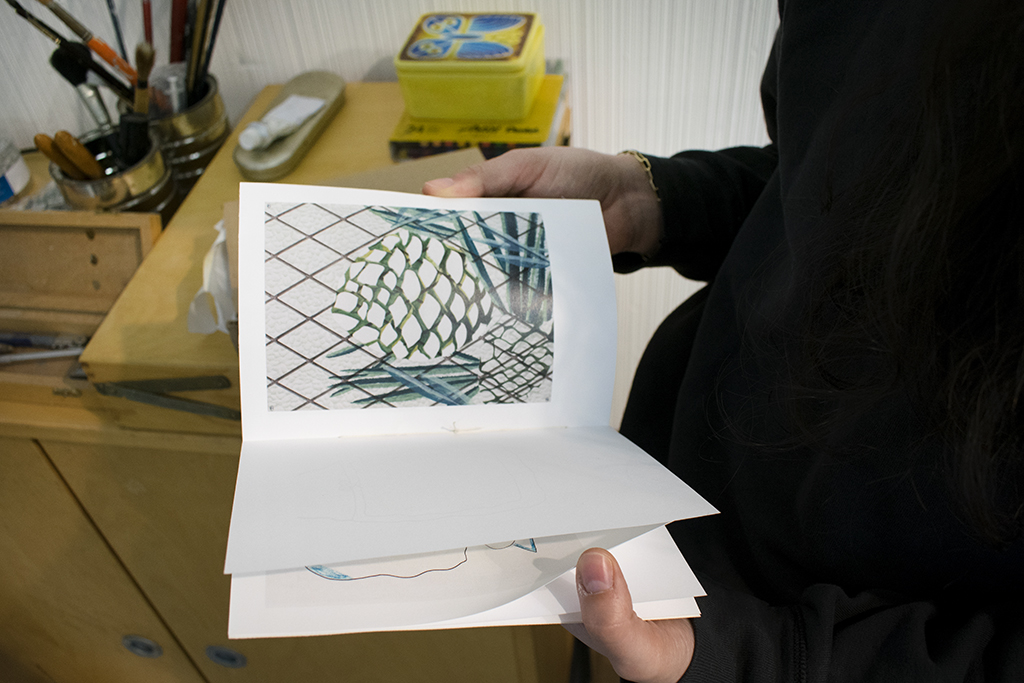

Over the years, I’ve been able to develop a way of working that satisfies a range of my interests materially. I’ve slowly honed a set of tools and materials that I constantly reach for and help do the job that I want my work to do. If we are speaking process-wise, I love the last part of mold-making where I get to see how a work came together, to figure out what might still be missing. Part of casting is not being able to see what something looks like until you remove it from the mold. There’s a shock that comes when you see the result for the first time, and then there’s the tension between how you imagined it in your head and what it actually looks like. That's a stimulating and dramatic moment. Finally, the process of trying to close the gap between these two things is really interesting because I’ve created a problem that I then need to solve.

There is a definite sense of function to your work, yet it does not actually act as a functional object. How important is the distinction between object and sculpture?

This is an important distinction for me because I am so interested in images. Something that has remained a persistent interest of mine in making work, has been to strike a precarious balance between a piece existing as an image and an object at the same time. Sometimes it's transitioning between flatness and volume, flip-flopping in a similar way as the duck-rabbit illusion. Other times, it can be the duplicity of a symbol and an object. The reason I never make the works functional is that I feel this would limit their reading too much within the world of objects. So many of my favorite artists are painters, and I look at painting all the time. I have always been interested in imagism, and this aspect is so important in my work as it exists in harmony with a three-dimensional object.

What sort of architecture did you grow up in, and how has that influenced your work?

I grew up in such a range of styles of architecture. I was born in Rio, and when I was a year old, my parents moved to Washington, D.C. Growing up, I went back to Rio almost every year to visit my family. The Tropical Modernist architecture there definitely left a strong impression on me, as well as the colonial architecture in other parts of the country and at a rural family farmhouse where we would spend. The architecture in D.C. is much colder and harsher. This is the architecture I spent the most time around. The outside of the buildings felt oppressive, but I have so many colorful memories of interiors–like my mother’s eccentric style of arranging things and problem-solving in the house. I grew up around people from all over the world, so stepping inside different family homes was always such a rich experience. Growing up I also spent a lot of time visiting Colorado and the suburbs of Denver because my stepmother’s family is from there. I have memories of sleeping over in her mother’s trailer in her trailer community, and swimming in the pool there. I think all of these memories have made their way into my work in one way or another.

Are you able to act spontaneously with your cast works? How much room is there for improvisation?

Definitely. Since my way of mold making has such a parallel to drawing and printmaking, there's a lot of room for changes and ad hoc decisions. Whenever I begin a work, I know what I want it to do and say, and I’m able to control the color and form of a cast towards that end. Though that casting step in many of the works is done essentially blind, there is room to edit, add, and transform the work during all stages of casting, even during the planning and mold-making phase.

Although clearly contemporary, your work has a definite vintage feel, due, in my opinion, to the craftsmanship and attention to detail. Is this intentional?

I wouldn’t call this aspect of my work “vintage,” but more like “broken-in.” The color palette I use has a lot to do with this, and it is definitely intentional. Many of the colors I use have hints of grey or create the effect of making the work appear almost bleached. My intention is to make the work feel as though it has lived as an autonomous entity, as a whole, with its own history. Because I make my work through a collaging of objects, or bricolage, it’s important to me that these separate objects read as a whole and are convincing in the fact that they belong together and exist together. This feeling that they are not brand new and are not synthetically spliced together, hopefully, helps the work be read in this way. Perhaps also what you are responding to as vintage has to do with the fact that, oftentimes, I use imagery or craft references that I see or remember from architecture or interiors in Brazil. When these kinds of materials come into the work, they carry with them sentimental or personal associations, and this, in and of itself makes us think of objects from the past as opposed to of right now.

You’ve participated in some prestigious residencies, Skowhegan, Sharpe Walentas. What are some of the biggest take-aways from those experiences?

Definitely all of the friends I’ve made. I spent such a long and intimate amount of time working alongside these incredible artists at both of these residencies. Some of the people I met at Skowhegan are like family to me now.

What’s coming up for you in 2020? Where can we see your work?

I have a show opening in February 2020 at Brennan & Griffin. It’ll be my first solo presentation in New York so I’m very excited! See you there?

Photos and interview by Jessica Ross.