Seeing Michael Jang's work for the first time, you might assume he's long been a fixture of the photography world. His work feels like it belongs alongside some of the medium's greats, part of a lineage that includes such icons as Gary Winogrand and Lee Friedlander (both of whom Jang was inspired by while studying at The California Institute of the Arts in the 1970s). For nearly four decades after graduating from CalArts and later SFAI, Jang worked as a successful commercial portrait photographer in San Francisco, all the while amassing an archive of thousands of images, the majority of which nobody ever saw. In 2001, he submitted a portfolio of his work to San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art. The photographs immediately attracted the attention of curator Sandra Phillips and soon found wider art world acclaim. Jang’s work is now the subject of a new monograph from Atelier Éditions, Who Is Michael Jang?, and a major retrospective, “Michael Jang's California,” at The McEvoy Foundation for the Arts.

Success is a tricky concept. You hope that the process is its own reward, that fame and prestige aren't your primary motivations, but who doesn't seek some level of appreciation, acceptance, and recognition? "If you were to have the choice," Michael Jang proposed to me, "of having fame early or putting it off for fifty years, which would you take?" It's an interesting question and one that I've continued to reflect on since visiting Jang in his San Francisco home ahead of his new exhibition. "Maybe fame isn’t the right word," he continues, "because that's not what it's about. It's just enjoying the whole process with your work and being engaged in it for as long as possible."

Alex Nicholson: I really enjoyed the series on your daughter and her friend’s garage bands. I hadn't seen that before looking through your new book.

Michael Jang: The kids that were there and I have been thinking that could have been the very last garage band scene before the Internet took over and kids literally started making music in GarageBand on their computers. It was a time when kids didn't have Internet or social media. You had to do something with your time and that's what we did from the 50s and 60s up to that point. I lucked into it through my daughter and her friends, I really wasn't thinking about doing it as a project. I didn’t see it as a book or show or part of a career because at that point I was done with all that.

I was in my fifties, it was actually kind of odd for me to be hanging out with 15-year-olds but I gained their trust once they found out that I'd photographed the Sex Pistols and The Ramones. Still, I was very careful because my daughter was involved. When they're that age you don't want to screw up. I knew I had a golden opportunity to infiltrate a scene. When you see punk pictures, it's not this young. They can't even go into a bar yet, they have no place to play besides garages. They would try anything, pizza parlors or even grabbing free electricity on the street from a Muni bus stop, just to play. I really felt for them because when you're young, you're very advanced in terms of your knowledge. While I downloaded Elvis, the Beatles and Stones in real time, these kids can actually download forty years of rock and roll in a year or two. Maybe it won't be as deeply felt, but they do get that information. It was their fantasy to have seen the Ramones. I said, “Oh wow, I've got stories to tell you.”

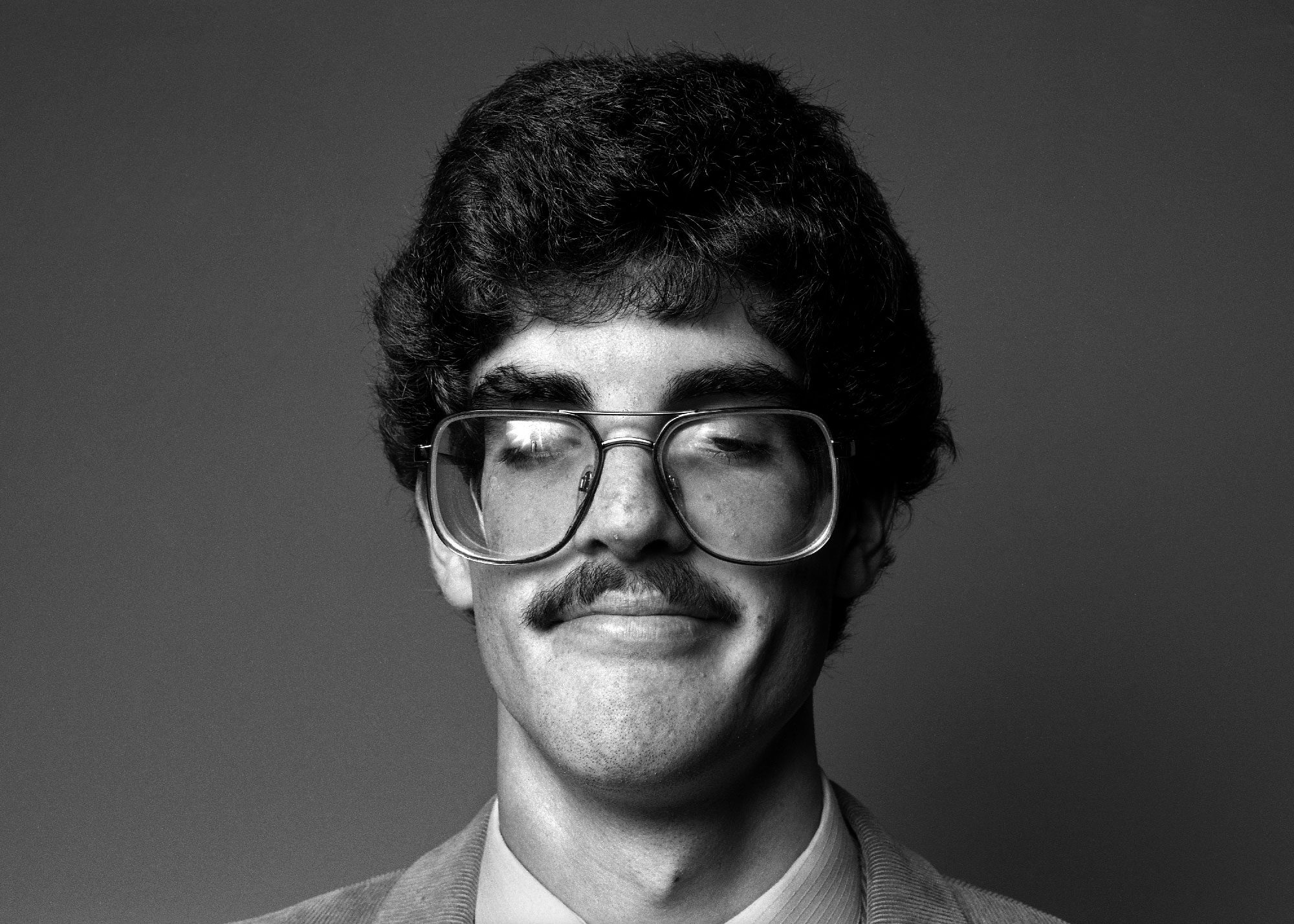

Untitled from "Garage Band," San Francisco, 2001

Do you think you would have approached it in the same way had you been younger and earlier in your career?

It's not so much that I would have photographed it differently, but because of my age and maturity, I saw them in a way they didn't see themselves. When you're that age, you think you’ve got it all together. They didn't realize that I was seeing them in the context of their youth and their energy and how wonderful it would be to capture it so they could see it later. We're trying to get these kids together to come to the exhibition. The ones that have heard about it can't wait and they're going to get it now that they have some distance.

When was it that you started thinking about the pictures you took in terms of time and how they might look in 20, 30, or 50 years?

Always. You know why? When you go to school one of your first classes is the history of photography. You're looking at old stuff, now, in the present day. You automatically make the connection. “Some pictures look old but aren’t interesting to me. Others are just as old, but they're still relevant.” I started thinking about why and how. This was the early seventies and the history of photography wasn't that old. You had some imagery which I had to be taught was good because I didn't see it. Like Walker Evans, It was a bit dry, like real estate photos. But to this day the work still has legs, why? Well, it wasn't terribly artsy. Artsy stuff can go out of fashion. We've been through a lot of things in photography like solarization or cross-processing, infrared, you know, just a number of things that immediately date it. I learned to shoot it straight, basic and with clarity. It ages better because you didn't mess it up. I never felt like an artist. I didn't say, “Well this is what I'm trying to do,” I just did it. Leica didn't make lenses really sharp for you to fuzz them up.

You didn’t intend to study photography when you first enrolled at CalArts.

CalArts was the art school out West at the time. In my hometown in Marysville, California I had been doing psychedelic light shows. I even made it to the Fillmore for Bill Graham’s shows. My parents saw that I was more interested in excelling in visuals than, you know, business and math and all that. So they let me go to CalArts.

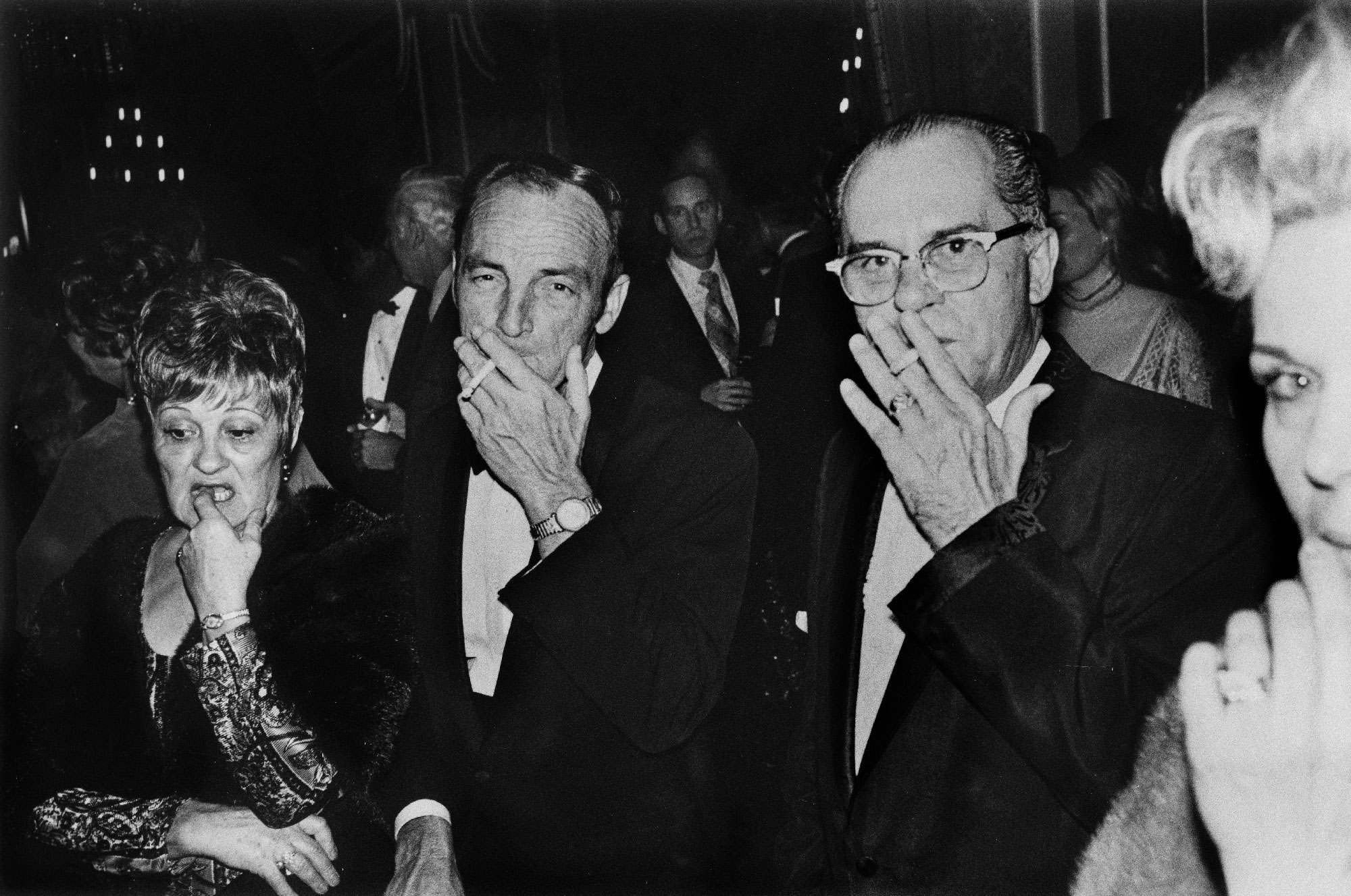

Couple Dancing, The Hilton, 1973

Can you point to a specific day or event where you understood that photography was what you wanted to pursue?

When the teacher showed Friedlander, Winogrand and Arbus. I saw it as a more natural alternative to getting a 4x5 or 8x10 and following in the footsteps of Adams and Weston. And nothing against the f.64 group but I didn't have a camera because I took the course as an elective. They had two Leicas you could check out and every weekend I went to LA. I started out taking pictures in the Beverly Hilton. I often would look in the newspaper for events like Ali MacGraw putting her handprints at Grauman's Chinese Theater. I'm there. You do that and you know you're going to get something, a bang for the buck for your time.

Sometimes if you're just walking the streets, you can go for hours without seeing anything. I thought, as much as I know that's who I'm studying and admiring, that kind of lifestyle is not going to be for me. I always arranged going to events because I knew there was going to be an apex at that event that I would be waiting for. That's kind of what I did even with the garage bands. I know that I'll get something in an hour or two. I'm practical in that sense.

You mentioned kids being able to listen to forty years of music and absorb it in a few months. Do you think it's the same with photography? A new generation of photographers can go online and learn the entire history of photography.

Just because kids have access to stuff doesn't mean they get it or understand it deep enough to learn. In real time it's paced out gradually and you could really absorb each Beatles album every six months instead of getting all of them in a week. You're not gonna know about how Revolver was right before Sergeant Pepper's and how important that shift was. You might know who Winogrand is, but you're only understanding 20% of what he's doing.

I've been telling people for a long time that you work with the tools that you have. Do you think if in 1973 I had a camera that I could also press a button and get video and sound, I wouldn't use it? You can take stills and get a movie and then have a show some day that moves and talks? Come on. I've been catching up the last five or 10 years because I'm back in that world again after being away for a few decades. I'm getting this wonderful opportunity to show my work and I'm going along for the ride and learning. There's so many different aspects to this. It's pretty wonderful to be going through this at my age, which is now almost 70. I kind of feel like I'm at a peak, you know? Go figure. Bill Daniel recently told me, “Michael, you are the master of the long game.”

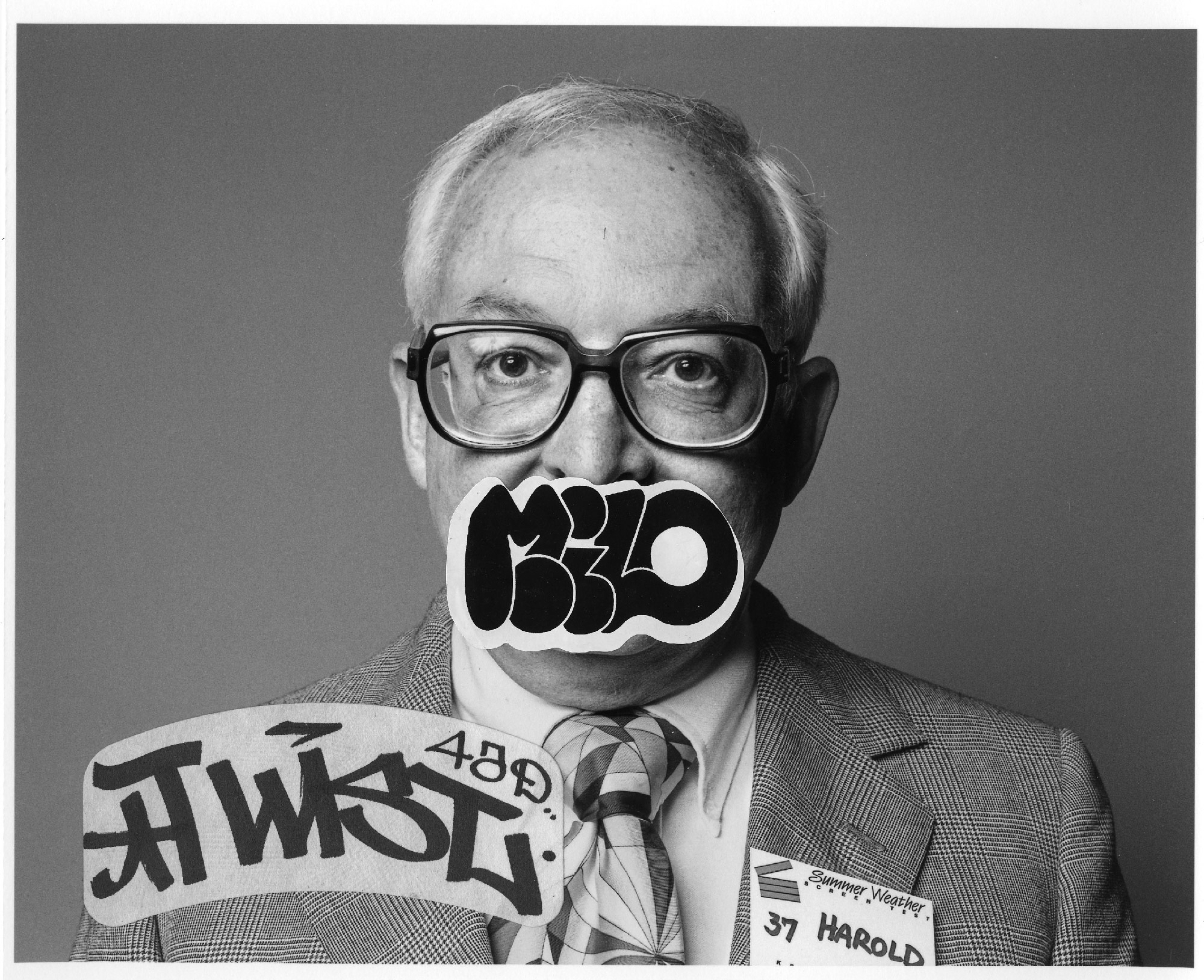

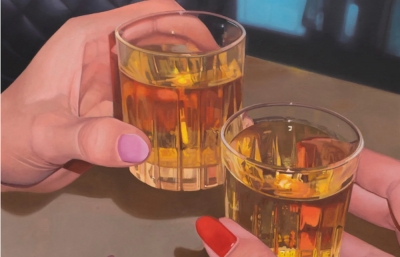

From the series "Summer Weather," San Francisco, 1983

Were you still shooting prior to all this?

Yes, but to make a living. Weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, magazines, editorial. Occasionally, if I was hired to photograph a marathon or something, it would end up being me shooting for myself a lot of the time. Like my series, "Summer Weather," that was a job. I think because I'm still me, the way I see things, is still could be interesting.

And you kept everything?

I've saved some stuff. I’ve also tossed a lot of stuff away. Thirty years later I found the negatives for head shots I did of some weathermen, I showed an assistant and he told me, “Michael, we have to look at this.” And that's how it goes.

Going through your archives, do you find yourself reexamining, not necessarily just the work, but what you've done with your life up until this point?

No, I didn't know what pictures were good. In school I would bring them into critiques and they would tell me which ones were good or bad and move on to the next assignment. That's why I didn't become a teacher, I couldn't even talk about my own stuff. How was I going to talk about other people's stuff? That's when I said, well, I know how to use the camera, so I'll just try and make a living with it. And that's when I did everything. Head shots, actors, models, rock groups. It was fun, I did it for thirty years until I decided I'd had enough.

Was there a particular reason you decided that?

I had an epiphany in the mid-90s. You hear about people being flooded out or hit by a fire, you know, what would you save? People always say they would save their pictures first. Well, I have a lot of pictures, so which ones? I thought, “Oh my god, this is a no-brainer. All the commercial work, even movie stars, toss it. All the personal stuff, save that.” I realized that what I was doing with my life, the commercial work, it was fine, but a lot of it was photographing celebrities and stuff for magazine covers. That's a dime a dozen. I got a handle on that, a perspective on what was really important. I could take a celebrity, and I did a lot of them, and toss that for a simple picture of a squirrel looking at me in Golden Gate Park with four Mormons in the background. I'll take that, you know what I mean? I don't know what that's about, but it was very clear to me what I would keep if I had to make a choice and run out the door.

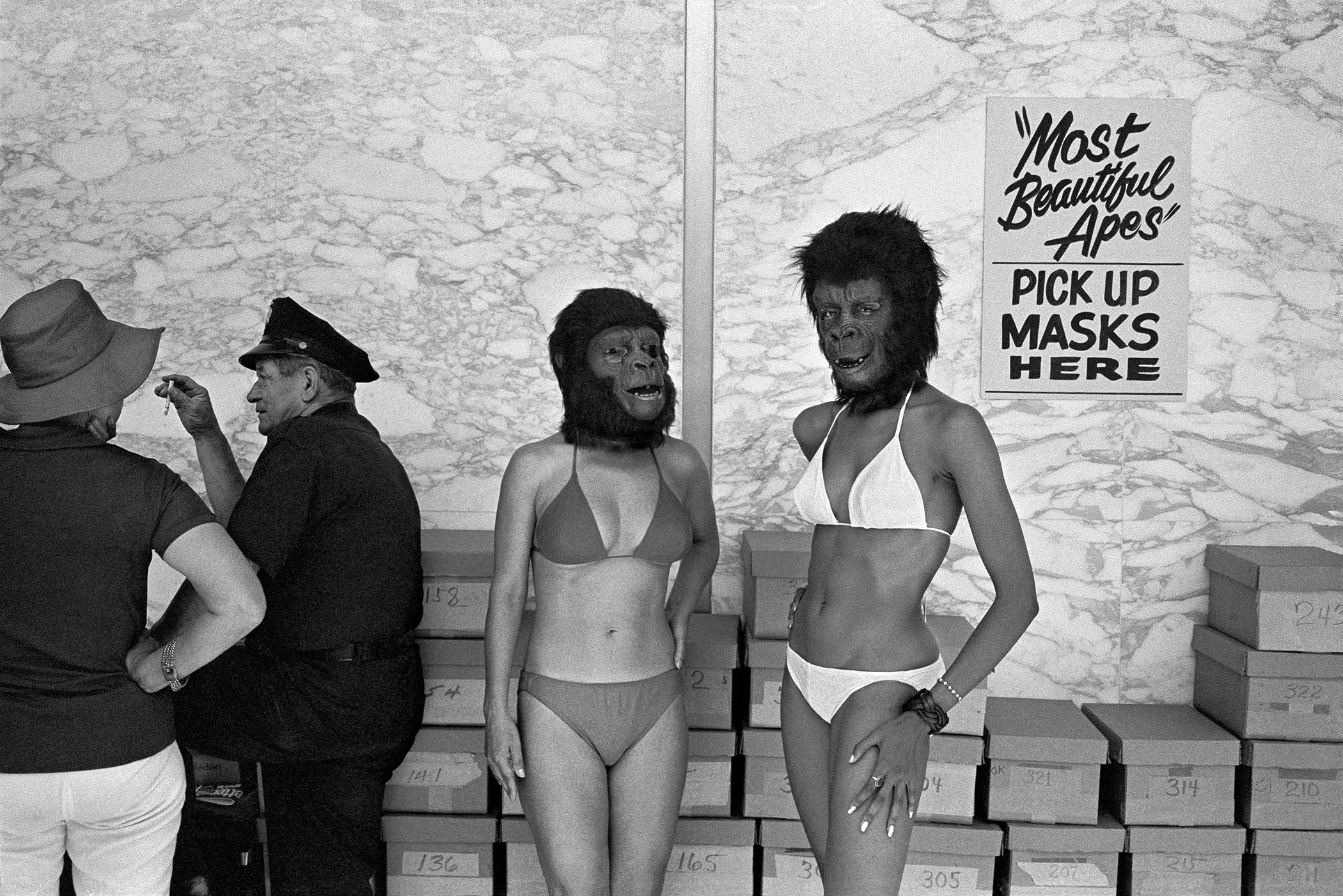

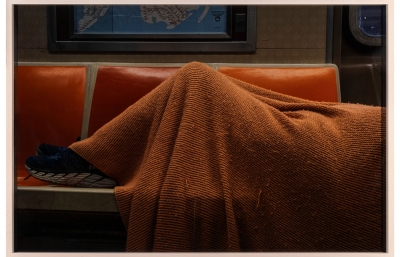

Planet of the Apes Beauty Contest, Century City, 1973

Looking at all your photographs, it seems like having fun is a big part of it, enjoying the process.

What's different is I've been alone for thirty or forty years since art school. You don't get a whole lot done sometimes. I don't think I have the gene to get out and call and make appointments and get it done. Teaming up with people was the key for the exhibition and the book. Teaming up with really great people that you see eye to eye with and who generally love the stuff. When I used to do editorial work, photographing successful people, I would ask them what their secret for success was. They would say, “Hire good people, people that are smarter than you.” I never forgot that. All these people are smarter than me in terms of editing decisions and their knowledge of the history of photography and where my stuff is within that.

Were you attracted to photography because it can be a solo practice?

While skateboarding and graffiti seemed to have more of a community than photographers, I still would have always liked it because the actual solo act of shooting is why you do it. I just shot. One of the things I learned from both Winogrand and Friedlander in person, when they came in to class and no one else heard it, is that they just shot. They were so far behind in printing and making contact sheets. They just took pictures everyday and I never forgot that. As a student, all my classmates would go out and maybe shoot a few hours a week and then spend the rest of the time developing and printing. Well, guess what? You've shot three hours that whole week. Everybody else at school was working six hours a day painting, ballet dancing, doing scales on a piano...

Have you always been pretty confident in approaching people and taking photos?

I still get nervous too. I think that’s almost universal. You master the art of being invisible so they don't see it coming. That's a whole other thing, how do you become invisible?

What did you discover about yourself by being a photographer?

I didn't know this until later, but I used photography to help be involved in the world. I would have no business going into the garage band scene with kids or crashing Frank Sinatra parties without a camera. I would be home watching TV. I realized that if I was at a wedding or some event, and was taking pictures, I wasn't really there socially because I would be in a strictly observational mode. That's when I started realizing that I need to put the camera down and just be. Rather than observing my family as an artist and photographing them, I need to ask, “How are you doing? What are you up to?” It's hard for me to do that. Photography gives you something to do. It's the way you can interact. It can be a crutch.

When you dive into a project like you did with your family what is it that makes you want to dig deeper?

I didn't dig deeper. It was simply a semester of work. Digging deeper suggests that I knew what I was doing and had intention. I was just like, “Summer's over, I'll see you guys!” I photographed my family occasionally for a few years after that, Thanksgivings and Christmases. It wasn't necessarily enjoyable for family get-togethers, but with the camera I was doing something, you know? Who would've thought all this would be happening with these pictures.

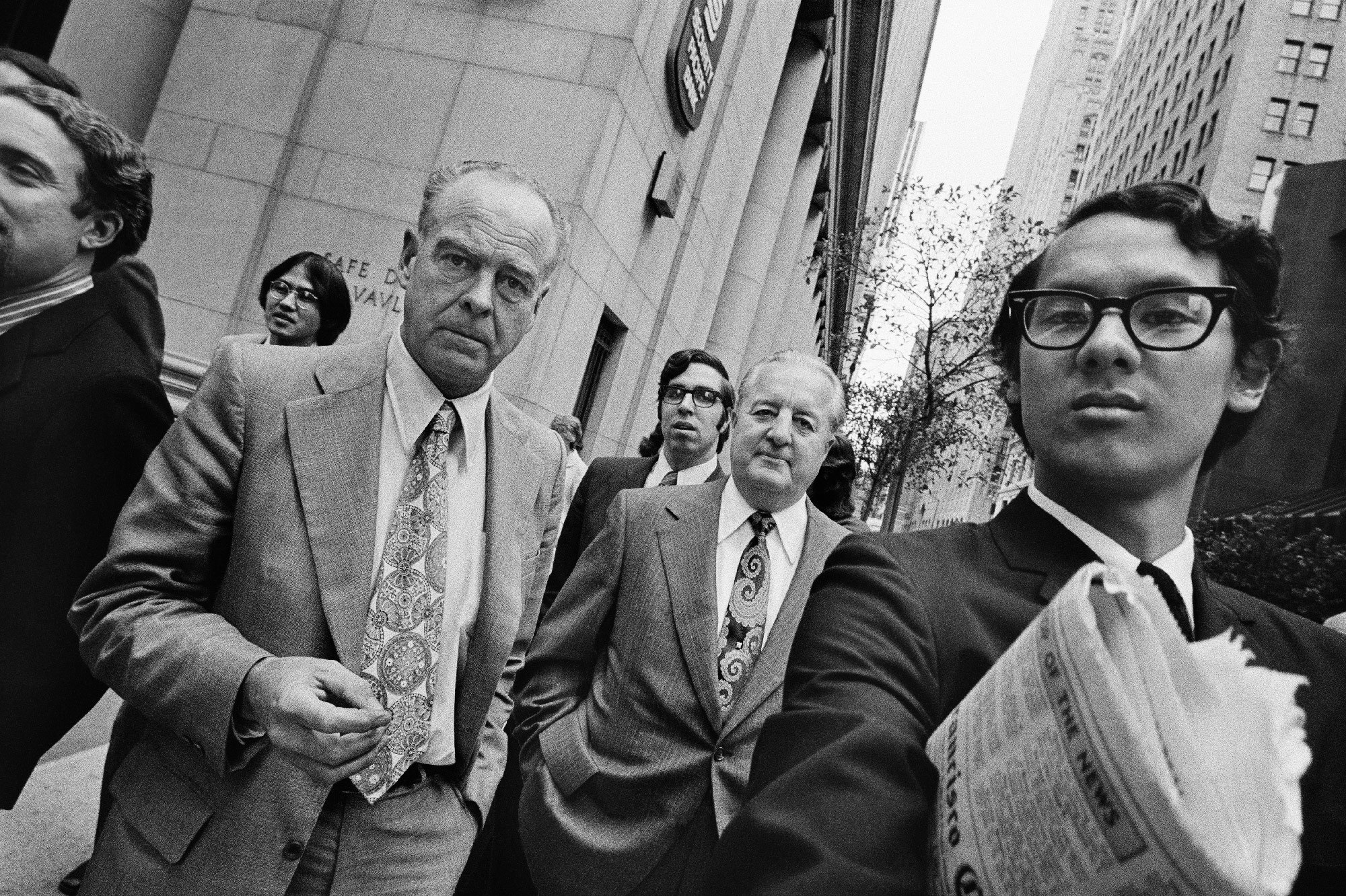

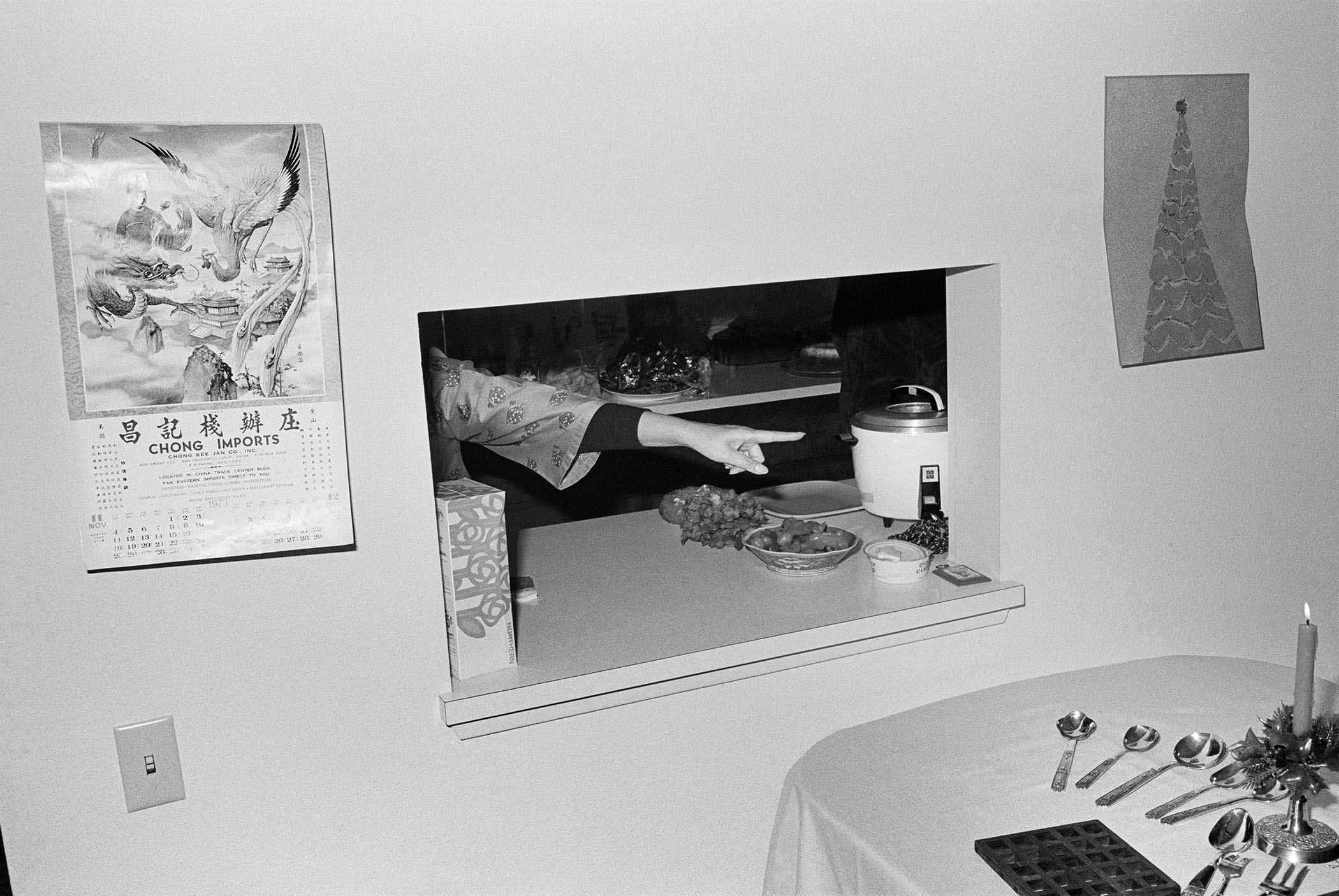

Holiday Preparations, 1973

Were your parents always supportive, even with you photographing the family at home?

There was no choice. I was never Harvard, Stanford or Yale material. CalArts didn't know where to put me. There was no school of mixed media or light shows, but they had music, theater, dance, film and a few other things and something called the design school. So they just stuck me in that and there was a photography elective that I happened to take. That's when it all started.

I remember concern from my dad. How are you going to make a living? He wasn't being critical, just asking a valid question. It was probably every parent's nightmare, their kid going to art school. Who comes out of art school making a living? But that's what makes this a unique story, and my parents are a huge part of it. How many Chinese kids in the 70s went to six years at an art institute and now has something to show for it? But it almost didn't happen. If Sandra Phillips at SFMOMA hadn't seen my photos... She's been coming over here for the last two years, going through everything. That's been a real gift, having her.

Have there been other decisions in your life, taking the chance and dropping your photos off at the SFMOMA, that changed your life in a big way?

I have no regrets and I actually love the way it's worked out. I'm not jaded. Everything is new and fresh and I'm thankful. If you were to have the choice of having fame early or putting it off for like fifty years, which would you take? Think about it. Maybe fame isn't the right word, because that's not what it's about, but it's just enjoying the whole process with your work and being engaged in it for as long as possible.

What's your plan for the exhibition?

We're in a new time and we have different ways of viewing this stuff. There are three rooms. The first will be sort of a reenactment of the 1967 MoMA exhibition New Documents with Friedlander, Winogrand and Arbus. We're going to put them in one room and Sandra Phillips will write a wall description explaining how they influenced me. The second room will be actual prints that I made as a student. The second half of the space will be where pictures get bigger and more fun. I'm showing how pictures have gone from 8x10 silver gelatin prints with a mat and black frame on a white wall to rough wheat pastings or being digested on social media. Room three will be full of more surprises and some collaborations.

Has this whole process of looking back at your archive inspired any new projects?

I can always go back into to my archives and print more stuff and it'll be new to me. Why would I be shooting something now when everybody is shooting everything and doing it better than I ever could. I'm not so great that it would be anything special. What I do have is stuff that you can't go back in time for. And that's my ace in the hole. That's the hand I'm playing.

I watch documentaries on TV. It could be about the Black Panthers or a rock thing and I’ll see something and think, I actually have something on that and I'll go look for it. There will be something and I'll just go, “Oh my God, I forgot about that!” That brings us full circle to Friedlander and Winogrand saying, “Just go out and shoot because that's it.” Do you want to spend your three or four years in school shooting or in the darkroom printing pictures that are probably crappy. These are decisions you have to think through.

My teacher once said, “You pay now or pay later.” If you're in a situation and you chicken out, you're going to pay later when you're looking at the pictures. Suffer now or suffer later. I never forgot that. Fear cripples so many of us. You always have to fight that. You may never get over it but it means that juices are flowing. I've learned that if I'm feeling that, it's a good thing. I like pressure. I like going into a situation where you might be out there for two or three hours, but the opportunity for the shot could be within a few seconds. You gotta be ready for it. Sometimes it’s like, “Oh shit, I got three shots left on this roll. Do I change rolls and maybe miss the shot or do it with only three in the chamber?” That's not a question now with digital, but I don't know if that's a good thing.

Who is Michael Jang? is available via Atelier Éditions. Park Life in San Francisco will be hosting a signing on Friday, Sept 27 from 6-9pm.

Michael Jang's California opens at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts in San Francisco on September 27th, 2019. An opening reception will be held on Saturday, Sep 28th at 5pm.