(Editor's note: This editorial was written for the Summer 2020 issue, in the midst of the early stages of the pandemic and the incredible quietness of the streets of major cities across America and the world. That silence is now the noise of real democracy and communal strength, where public spaces are now being taken back by the people, those quiet places are now the epicenter of real public action. The sounds are back, the streets are alive; and in at the time of this essay, the quiet was so apparent. As a magazine that champions public art, street art, protest, interacation on the streets and ownership of public space, we continue to support the protests. And yet this essay we hope provides a time capsule of that quick moment of deafening pause. But we are alive again.)

“It is in the thick of calamity that one gets hardened to the truth—in other words, to silence.” —Albert Camus, The Plague

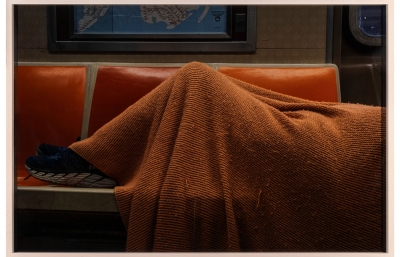

How will we remember this pandemic? Will it be in the portraits of individual suffering, the bedlam of hospitals, prisons and other institutions overrun with disease and death, the visage of our health care workers and first responders battling and sacrificing against all odds, or those of many politicians too clueless and selfish to comprehend, let alone fix this situation? Tragedy offers endless drama for art, and death is by any pictorial measure somehow iconic, but when it comes to mark and remember these days of grief and confusion, many of us will likely take away from them a terrible silence and profound sense of isolation. Bryan Derballa has taken the pictures of this time that are not so much those that we will remember, but those we will never forget.

Plague has long played an invisible hand in the shaping of our culture, from the ancient Greeks for whom it was a cruelty of the Gods brought upon the people through the folly and hubris of their leaders (which seems as contemporary as myth can get) to centuries of Western Art where the traditions of Allegory and History Painting distilled it as some sublime conversation between grace and destiny, with masterworks from the likes of Bruegel, Caravaggio, Poussin and Titian. These are the stories that history tells us, memories of mortality where hardened truths are somehow lost over centuries. In Boccaccio’s The Decameron from the mid-fourteenth century, ten people hiding out in a secluded villa to escape the Bubonic Plague tell one another 100 stories, myths and fables, perhaps not so unlike the movies we now stream to fill the void, diversions and amusements to help explain the world. What will be the stories we tell? Will we have words for the unspeakable, pictures for what is largely described as an invisible enemy?

Stark and unrelenting as a barricade or vacant street, I like the solitude of Derballa’s vision, and the quiet, a desperate still that moves only out of necessity, crippled and benumbed as if in trauma but agitated by all that uncertainty, anxiety and ennui. Quotidian and yet utterly fantastic, this will be how most of us experience the new age of quarantine, especially we urbanites for whom the great cities of today have represented a level of density, interconnectivity and possibility as never before. This is what it looks like when the world shuts down, the society of the spectacle unwinds and we are forced into an equivalent of the most diabolical torture humanity has invented, solitary confinement. It has no face, for like the plague doctors whose masks are still worn for carnival in Venice, our identities are subsumed by the new habits of protection. Rather, it moves like furtive shapes in a theater of abandonment, no less than six feet apart, never touching, alone together. If photographs are but a sliver of time, when time stands still, they are timeless. —Carlo McCormick