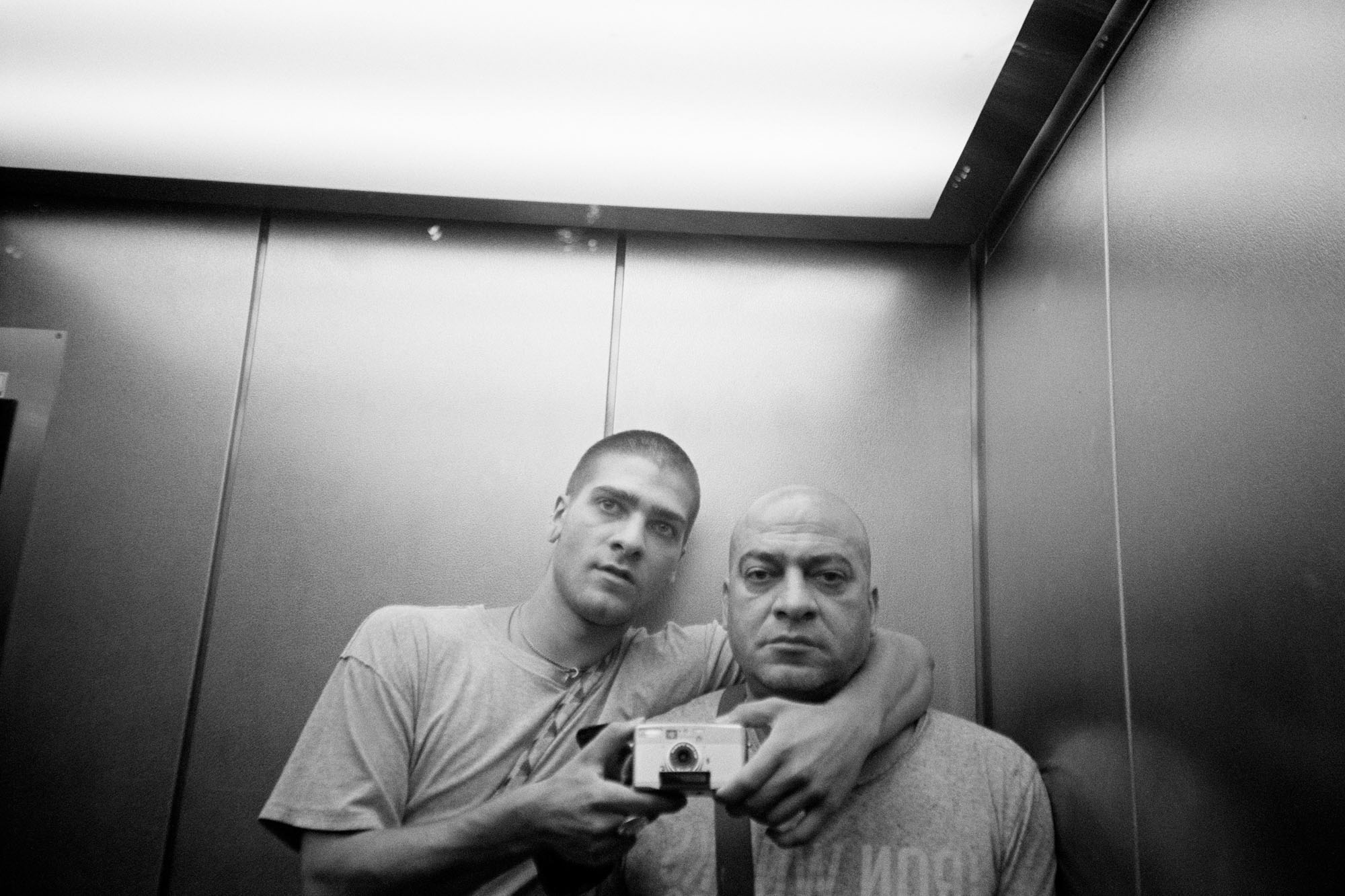

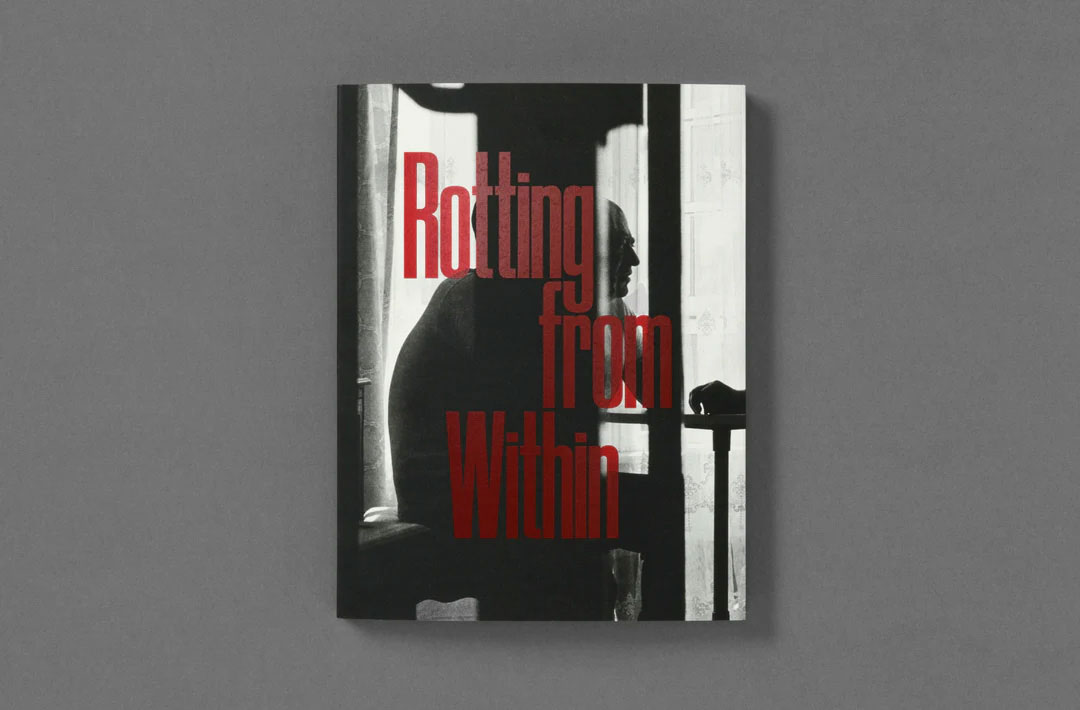

This summer, Abdulhamid Kircher will publish a book of photographs with Loose Joints entitled Rotting From Within that encompasses his entire life. They will also encompass lifetimes. The camera is a peculiar instrument. It can be an invitation to cultivate connection and also pretext to remain forever meters away. It can be a portal into other worlds and a reflection of one’s own, a guise for concealment, or a revelation in itself. As a teenager entranced by photography and hungry for experience, Kircher was compelled to capture the present and unwittingly found his way into the past.

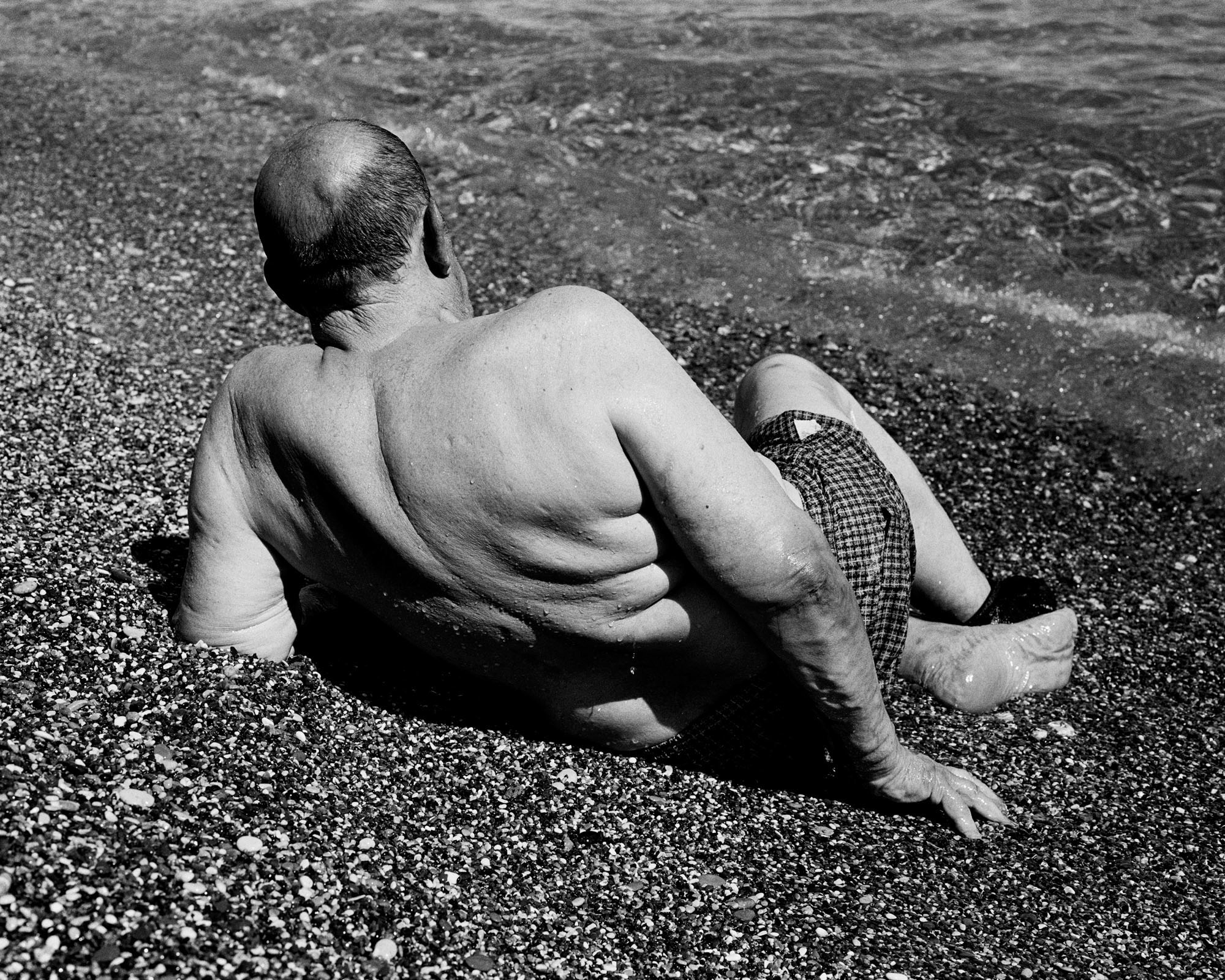

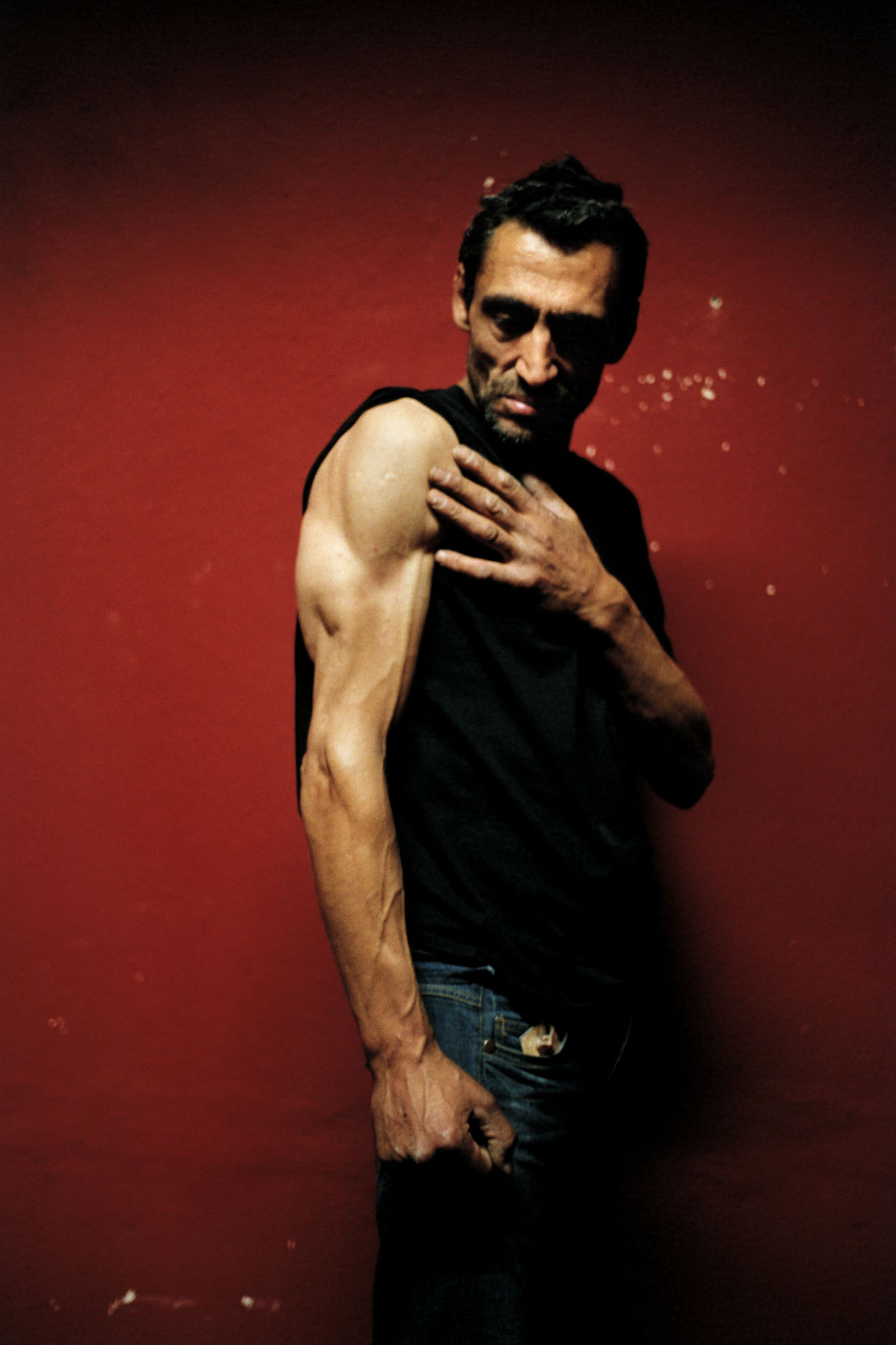

Raised in New York by his mother, he returned to Berlin in 2014 and began spending summers with his father, who had recently been released from prison, as well as extended family in Turkey. Kircher describes the title of this body of work, Rotting from Within, as a reflection of latent feelings in this found relationship with his father, as well as the inherited trauma entrenched within the male figures of his family. The journey of unearthing his own identity amidst legacies passed down is an ever-evolving story of lives folded into one another, of irreversible creases, torn, weathered edges, and ingrained pasts untangled from the potential of an unwritten future. "I can see it as an observer," Kircher tells me, "but can any of us really see something as it happens to us?"

Alex Nicholson: How old were you when you started photographing your dad and his world?

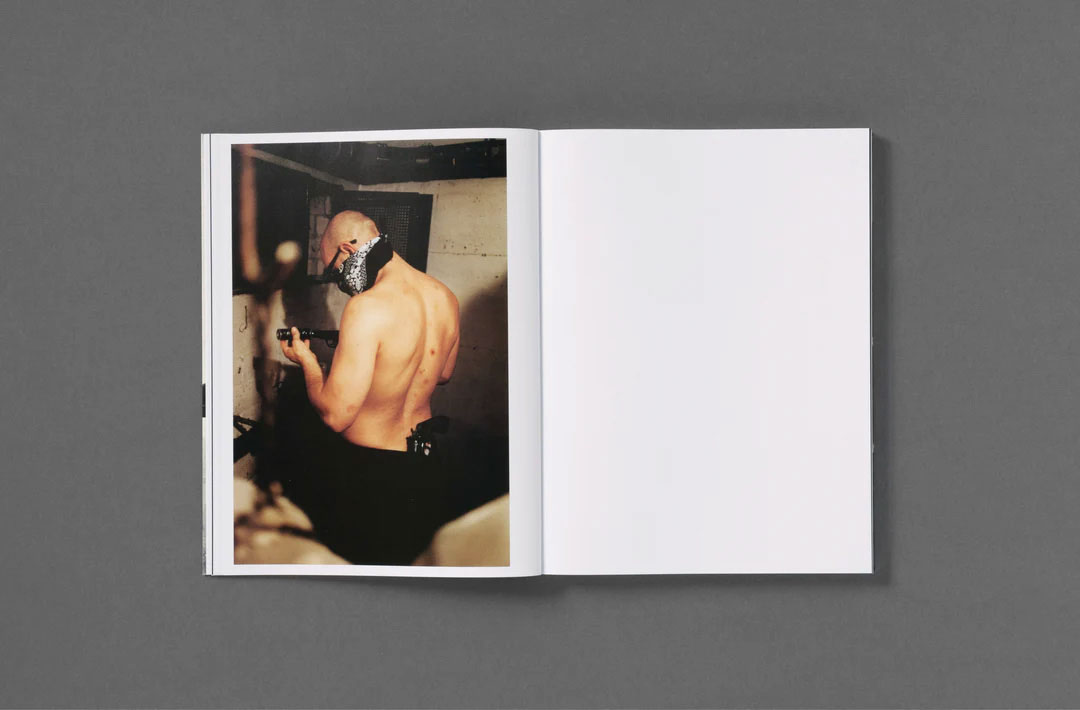

Abdulhamid Kircher: I was so young, probably 16 or 17. I had only just started taking photos and was trying to get access to anything I could; and with my dad being a big drug dealer, it opened up all these doors.

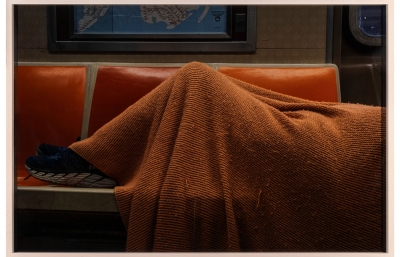

All images © Abdulhamid Kircher 2024 courtesy Loose Joints

All images © Abdulhamid Kircher 2024 courtesy Loose Joints

How did it work? Were you automatically around these things when visiting him?

Yes, it was just his everyday life. All these people surrounding him—his friends, his customers, the places they went and lived—fascinated me in the beginning. For instance, my dad would give me a certain amount of drugs and then send me off with his customers. In exchange for letting me photograph them in their spaces, they would get the drugs my dad gave me. It got really bleak because it would just be me alone in all these bizarre scenarios. Sometimes it doesn't even feel like it was real.

How do you understand it now?

When you're that young and you see a lot of crazy shit, I don’t think your brain is able to comprehend what's happening in front of you. It was too much. Now I can see that maybe, at first, my dad saw it as his way of rebonding and us getting to know each other. He could see how excited I was about photography, and maybe he felt like the only thing he could provide was access to his world, as fucked up as it was.

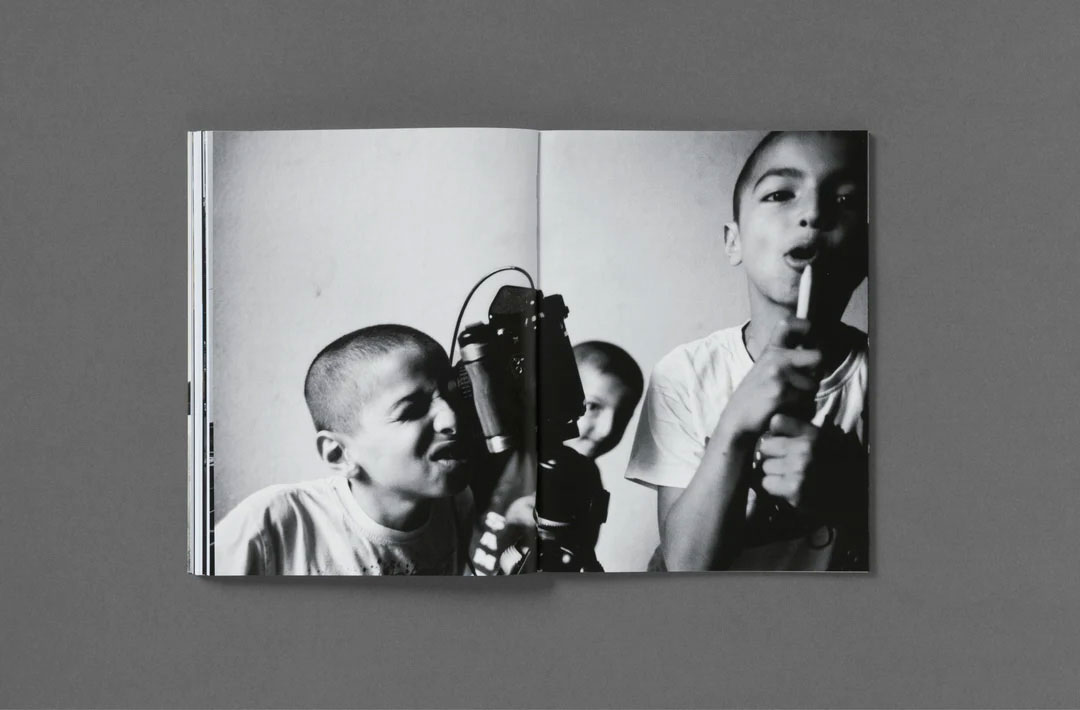

What kind of things did you photograph before this?

I started taking photos of kids in my high school messing around, doing drugs, or whatever. I loved being out in the city, and it gave me a way to get closer to people I found interesting. Then, when I was off from school for the summer, I’d go spend a few months with my dad in Berlin. There were such large breaks in between visits that every time I went back, making this work and the processing of it felt very disconnected. That's why I'm sequencing the book somewhat chronologically; I want it to feel the same as it did for me throughout those years.

How did things change as you got older?

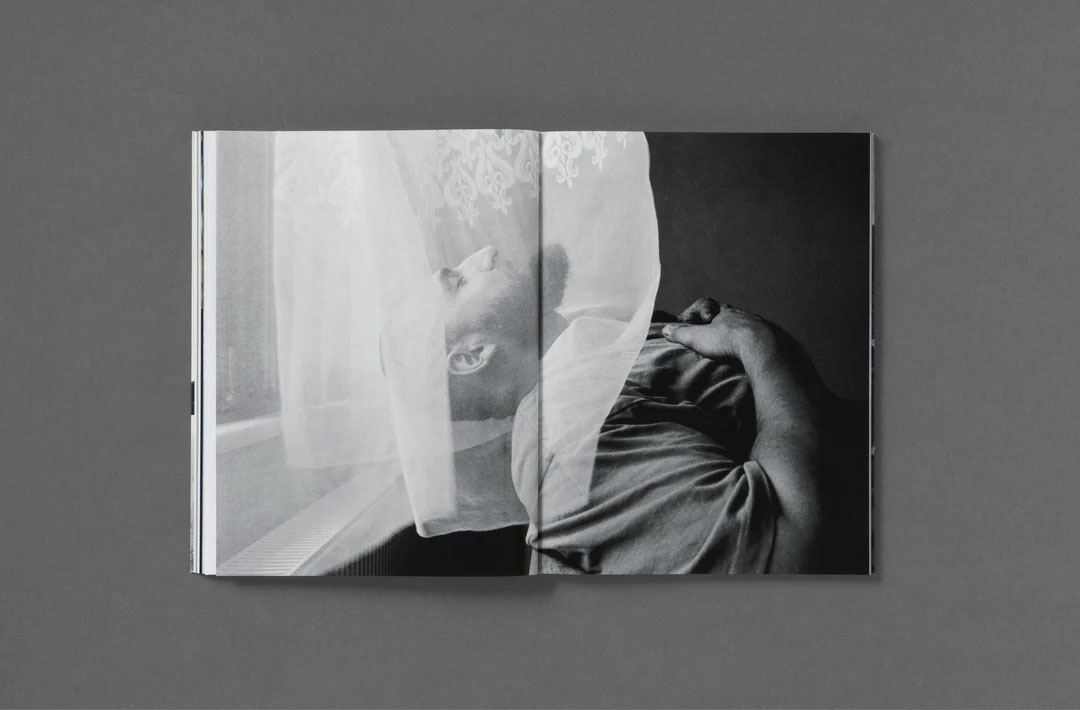

The relationship with my dad started to fray… I began to understand who he really was and his abuse towards me and my mom growing up. I think this rift caused me to focus on where he came from, and the environment in which he grew up. I obviously couldn't go back in time, but I could spend time with the people who raised him in Berlin and Turkey.

I kept a diary the whole time. There were so many feelings and thoughts I was undergoing while these images were being made. It wasn’t until grad school that I began digging through all the diaries and photos, trying to make sense of everything.

Which moments really stand out?

A few years in, I saw my dad beat someone up in front of me. In that moment, I was so focused on taking photos, but then the next day, I woke up crying. The reality of what had happened suddenly hit me. That’s when I’m grateful that I was adamant about keeping a diary because I can look back and know exactly what I was thinking when certain photos were taken.

You had a pretty strong drive for documenting and capturing everything around you from a very young age.

I think I've calmed down now, but there was a point where I was really hard on myself. I became so obsessed with trying to capture every single moment of my life. It took a toll on all my relationships—with my family, my partner, etc. It was bad. If I missed a photo, I would beat myself up for weeks.

Does that obsession feel present as you go back through all the work for the exhibitions and the book?

Every time this body of work is shown, it’s different; my partner and I make the installation on the spot. It’s a mix of photographs that I’ve already printed in the darkroom or the drugstore, but I’ll also bring a physical printer into the space, which allows us to be reflective in real time. I can create something that represents now, rather than trying to pre-write some sort of fixed narrative. A book feels more solid, so that’s been a different challenge. Working on something that will be fixed and exist in one way forever is daunting. But at the end of the day, you can work on an edit for years and years, and that doesn’t mean it’s going to get any better.

How important is the type of camera you shoot with and its impact on the moment captured?

A lot of people say that it doesn't matter what camera you use—that if you're a good photographer, you'll make a good image; but I think the cameras I choose play an important role in how I perceive what's around me. They allow me to process the world at different levels and, in a way, at different speeds or paces. At one point, I started getting a lot of unique cameras, like a macro camera that was used by dentists to photograph teeth or a half frame camera attached to a pair of binoculars. I was interested in how I could perceive a situation differently than from the standpoint of a human’s field of vision.

Has your family seen the work? How have they reacted? How do they see it?

Has your family seen the work? How have they reacted? How do they see it?

I don't think they really understand the scope of what I'm trying to address, especially in the context of generational trauma. They are excited to see family members and photos of themselves, but I don't think they're really thinking about it beyond that. And this is by no means speaking badly about them; it’s just that when you’re inside something, it’s hard to see it objectively. I can see it as an observer, but again, can any of us really see something as it is happening to us?

I'm a bit nervous about the exhibition in Berlin this summer; it will be the first time many of them will see the work in person. They all know what my dad’s up to, but no one talks about this secret that everyone knows about.

What about your dad himself?

He takes no responsibility for anything, and that's the same way his parents are. That's where it all stems from. There's just so much heavy baggage that I don’t think he could ever come to terms with. I think it would destroy him if he actually tried to start.

Do you think all this reflection, this work, this observation, and this sharing of all of it contribute to allowing you to chart a different path?

My dad was abused every day. He was never allowed to show his emotions, never given a hug, or shown any type of love; of course he was going to turn out the way he did. There's no way around it. This story is specific to me, but this narrative is so common in fatherhood. It let me know from an early age how lucky I was to have my mom. She had me when she was 15, and in a way, we grew up together. I'm grateful for the life she created for us in New York and how she was able to survive and create this foundation that my dad and his family didn’t have, and that I stand a chance of writing something different.

Rotting from Within by Abdulhamid Kircher is published by Loose Joints. An exhibition of the same name opens at carlier | gebauer in Berlin on June 29, 2024.

This article was originally published in our SUMMER 2024 Quarterly.