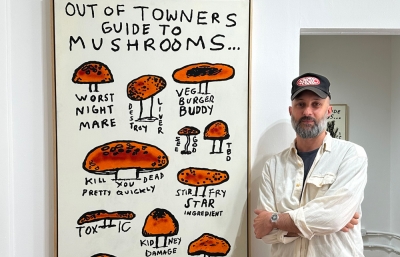

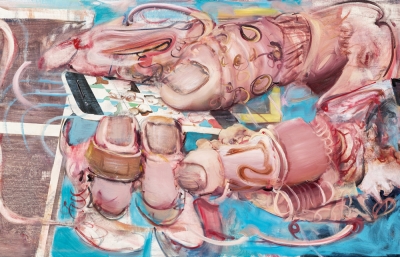

Playfulness isn’t typically associated with danger, especially in the graffiti scene. But for artist GATS (Graffiti Against the System), play and a bit of whimsy have become integral parts to staying honest—to staying dangerous. Their newest solo exhibition with Harman Projects, Midnight, GATS recontextualizes the familiar masked face with a sense of play and irreverence,leaning into the freedom of being a masked figure themselves.

Before the exhibition opened, GATS caught wind of a few queries from Harman Projects. Below, the artist discusses a new sense of play, lessons they’ve learned over twenty years of artmaking, and how Halloween and graffiti aren’t so different.

Harman Projects: There’s a sense of play in this new body of work—the mask figure themself even seems to be having a bit of fun. We had spoken about this sense of play emerging from a desire to be free from the desires of others.

GATS: The world has been really heavy as of late, and I feel a deep need to find relief through playfulness and humor. There is a lot of risk taking in the graffiti art world I exist in and that often, and unfortunately, leads to a lot of loss within our community. This new body of work is both a way to honor the lives of our friends that we have lost, and an offering to those that follow my work as a reminder to find ways to appreciate life in the wake of such intensity.

Graffiti and street art have their own life cycle. You completely put yourself into it and it often disappears the next morning. For every piece of my graffiti that you see, there were a bunch more that no one ever saw. That makes it hard to stay motivated and it often comes up in conversation with other artists working in the street. What constantly comes to mind is a conversation I had with N.O. Bonzo. When asked why we do this, they said, “It’s self defense for the soul.” This reinforces why I’m striving for playfulness and humor within the work. It’s self defense for the soul. Little acts of resistance against the doom and gloom of the world.

Well, that and I’m trying to take myself less seriously. I’m trying to distance myself from the work in the sense that it’s something channeled through me but ultimately isn’t me. This way I’m able to continue on when the work is criticized, or physically destroyed, as is the nature of work on the street. If you take it as a personal attack your mind will cave in on itself. It’s also necessary for the work to evolve. If you are worried about people liking you, you will become aesthetically stagnant, afraid of taking the risks necessary to evolve. Allowing yourself to be silly is often seen as a vulnerability in the hyper masculine graffiti world. Everyone wants to appear tuff so that they feel safe, but good art isn’t safe. To be honest, being yourself or being different isn’t safe. But I don’t know, fuck it, lets get dangerously silly.

When we last spoke, you mentioned that you had wanted to do a Halloween-themed exhibition for some time now as you felt the spirit of Halloween bears similarities to the spirit of graffiti: running around after dark, learning that there is power in being something on the fringes of society—something deemed not “good.” Can you say more about these parallels?

Halloween definitely got me hooked on the excitement of anonymity and late night pranks. As a kid it was the one night you had power. That neighbor who yelled at you for waxing the red curb… he’s getting egged tonight. I’d plan out a whole mission, mapping out streets, what spots yielded the best treats and who your crew was going to be that night. It was this kind of role playing as a villain, trickster or ghoul that empowered me to express myself in the form of a character that I could construct and build upon myself. It was a lesson in self agency.

When I started tagging around sixth grade it was first with that temporary spray hair dye from the Halloween store. I didn’t have any context of graffiti, I was just like hey, we can write our nicknames on walls with this.

Did you ever have a favorite costume as a kid, or do you have a favorite costume now?

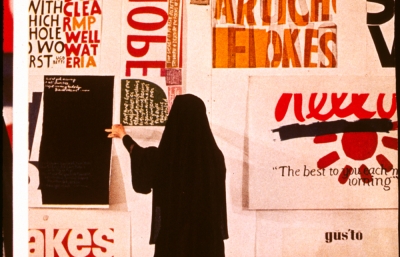

My favorite costume as a kid was Death. This big black hood, my face blacked out by a nylon stocking, and a huge scythe. I suppose I still feel that way wearing a black hoodie, a ski mask and holding an extension pole.

You started writing GATS almost twenty years ago in Los Angeles, where you are now having a solo exhibition in an art gallery. When you started writing GATS, what did you think you would be doing twenty years in the future?

When I started writing GATS I assumed I was likely going to spend a good chunk of my life in prison. This made it difficult to plan for a stable future. I was focused on activism and training to fight instead of taking school seriously. I felt I had nothing to lose and kept diving deeper and deeper into doing graffiti every night. You have to remember that at this point there was no future in graffiti. Keith Haring and Basquiat were popular by then, but I was unaware of them. New York was a foreign country to me until around 2007.

People seem to not understand this, but graffiti was a way to keep me out of trouble. A way to have a voice in the world and subvert power without getting crushed in a head on attack with a superior force. Everyone has a social media profile now, but back then the street poster was the political meme.

The idea of having a large solo exhibition in Los Angeles was something I couldn’t even perceive as being a possibility twenty years ago. I don’t know if it would have been something I wanted twenty years ago. When you’re young, sometimes you resent the people you look up to because you want what they have but it’s so impossible to perceive that it will take 20 years of work to get there.

Any inklings for the next twenty?

I would like to find a more solid way to give back, support young artists and provide a space for community. I think about all the people who kept me alive and encouraged me and I want to become that for other people. Dane Goodman told me, “There are two types of artists. Artists who help other artists and artists who don’t.”

Jon Paul from Political Gridlock used to let me burn screens and print at his shop. He would let me tag along and side bust art shows in LA and Rome… kind of lurk in the background of more significant artists. I learned a lot. I’ve always dreamed of opening a community print shop with a free wall out back. A center point for people to hang out at. I don’t know how to fund this and I don’t know how to mesh it with my anonymity but what I have learned from all successful artists is that no one does it alone.

A connection to nature and our relationship to the environment are running themes through your work. I also saw you mention that you don’t like sharing the locations of your more remote pieces so that folks can accidentally have a nice day in nature looking for them. Do you feel like your practice retains this connection to nature, even if the materials may have shifted?

My process still depends very much on getting out into the world. If I sit in the studio without having first spent time in nature or a new place my creative output screeches to a halt. No input, no output. And my work wouldn’t exist without the context of the outside world. The two go hand in hand.

The pen and ink illustrations I’ve been working on the past couple of years are usually done outdoors in one sitting. I hike out to a beautiful spot and don’t leave until the drawing is finished. This forces me to work in quick concise strokes. It’s very meditative. The mark making is expressive and contains a lot more energy than my more precise line work. While I wait for the ink to dry, I explore the surrounding area looking for interesting sticks to make into handmade dip pens. The uniqueness of each pen lends to a wide variety of line quality. The pens themselves become pieces of art, each containing an origin story contextualizing the object and the illustration. The drawings pick up little splatters of spring water, grits of sand, and other evidence of the adventure further contextualizing the narrative.

My canvas paintings are mostly based on sketches I made while in these outside places. Often, the color pallets I work with are meant to reflect nature. I’ve always been attracted to minerals oxidizing. You can find it happening on natural rocks or rusty fences in the city. It’s one of the things that connects the aesthetics of the two.

Some of the works in this show are framed with wood from signs found in the city. We fill our homes with things that remind us of the outside because we were not meant to live in isolated white cubes. Organic objects all have individual character. A stick is already a priceless piece of art to me and I’m just trying to honor that and share with others how I see the world.

Speaking of your materials, you almost always incorporate found objects into your gallery exhibitions, creating a material history of the places you’ve been and things you’ve given value or attention to. Are there specific found objects in this exhibition you want to highlight? Any with particular sentimentality or just a good story?

Creating the narrative of experiences and places I’ve been to through material and objects is a huge part of my work. It’s almost like a mapping project in some ways in that each piece comes from a different place I’ve been to along the way. In turn they all hold a sense of sentimental value to me. One of the ceramic masks in the show is speckled with volcanic sand from one of the beaches I made ink drawings at. Each piece is related in one way or another, helping to form the greater context and story of the work.

Your style is really unique. Taking the train into the city from Oakland, you see probably hundreds of pieces on water tanks, highway barriers, warehouses. Some of them look like each other, but none of them look like GATS. Can you say who some of your favorite artists are, graffiti and otherwise?

What influences me more than the aesthetics of other artists is our conversations. Ideas, strategies and the love of mediums and processes.

When I was starting, I noticed that artists would get famous for one thing. The giant piece guy, the wheat paste guy, the mosaic guy, the sticker guy, the tagger, the printmaker, the painter. I thought, why would anyone limit themselves when you could use all these tools? That’s why Revs and Cost blew my mind when I found out about them. They were doing rollers, wheat pastes, public journal entries, and sculptures. There was no line between graffiti and innovation. That was the mentality I wanted.

I have to give a huge amount of credit to my crew, PTV. It is an art movement for sure. We didn’t know each other at first, but seeing each other’s work in the streets drew us all together and we have been influencing and supporting each other ever since. That’s what’s unique to the graffiti world versus the larger Western art world. In graffiti, you’re very defensive about people outside your crew copying your style, but within the crew you’re collectively developing a graphic language. This is because you’re invested in the good of the group and friends carrying on a legacy that stretches beyond yourself.

Conversations with Takashi Murakami shifted my work. He recommended I express a wider variety of emotions with my characters. When he asked me to paint a large number of skateboards for an installation at The Vancouver Art Gallery for Juxtapoz x Superflat, within a months deadline, it forced me to really deconstruct, abstract, and experiment with my character because I couldn’t have forty paintings that looked too similar. Working with him and seeing his process made me realize it’s ok and actually necessary to ask people for help.

Afterwards I got a bunch of friends together and built a ten foot tall sculpture. It was simultaneously the most fun and stressful thing I’ve ever done. I would love to do more stuff like that if anyone ever offered me the space and funding.

Something I thought was interesting about this new series of works was an acknowledgement that, in a way, your art and graffiti career has been rooted in a “refusal to grow up.” Not a refusal to mature, but to adopt the homogenous norms of adulthood. But the youth culture of the 80s and 90s also grew up, permeating into professional sports and the fashion industry. How do you see the younger generations pushing against the norms we adults have created now? And how do you continue to engage in refusal?

I can’t so much speak for the younger generation, but I can attempt to sum up some of the things that it means to be young for every generation and how one can carry those values with you later into your life. To be young is to not accept rigid rules of what you’re told the world has to be. Carrying that mentality with you will ensure your ability to believe in possibility. Being young is doing new things without the self-consciousness of not being good at it yet. Often when an artist or musician becomes good, people still just like their early stuff when it was raw, angsty and not concerned with being good.

When you’re young you do things for the love and enjoyment of it without thinking about where it’s headed. You have to be in the moment for things to mean anything in retrospect.

What’s a lesson you wish you had learned earlier in your career?

If I were to teach my younger self a lesson, I would remind younger me that perseverance pays off. It can take years for your career to evolve into what it is today, but it’s important to keep building and to keep planting seeds. I promise that they will grow. Your art will take you to places you could never dream of. Keep going, stay fluid, and be ready to shift and pivot as you go. It can be a struggle at times, but the adventures you’ll have and the community you build through your art will be the biggest and greatest reward.

GATS’s solo exhibition Midnight is on view at Harman Projects Los Angeles at 2754 S La Cienega Blvd. through November 2nd.