It almost feels like a crime to call Sarah Sitkin a “designer.” Her sculptural work combines so many elements of fine art, set and costume design, not to mention just plain old “Oh my God, how did she do that?” art that doesn’t succumb to labels. From solo shows at Superchief Gallery in Los Angeles, where we first caught her work in person, to new sculptural works for the SyFy channel’s excellent series, Channel Zero, Sitkin is redefining that narrow margin between fine art design, traditional special effects and production design. A childhood growing up around her family’s hobby store in the heart of the film industry has led Sarah to create her own cinematic vision, where explorations into silicone, clay, plaster, resin and latex have made her current body of work one of the most fascinating in Los Angeles today.

Evan Pricco: I guess you would consider yourself a sculpturist, but it goes so much beyond that with elements of set design in your recent works. What, at this point in your career, do you call yourself?

Sarah Sitkin: I have always had a hard time describing my work in general terms. It does incorporate set design, also costuming and sculpture. I would just call myself an artist. I try not to limit my creative ideas to one field or title.

It seems that, especially in Los Angeles, the role of the costume or set designer leads one to Hollywood, and in that, perhaps a lot of training and schooling to get there. Did you have formal training?

I never even got a high school diploma. I was a classic bad kid, in and out of different school programs until I was old enough to permanently ditch class forever. Everything I wanted to know, I could just search on the internet instantly, from anywhere in the world, for free. I tried taking some community college art courses, but didn’t last more than a few weeks before I was over it. I worked all through my teens and early twenties at my family’s hobby shop. Kit Kraft introduced me to everything. The shop was located in a magic place in time—right in the heart of the Los Angeles special effects industry in the late 1990s and early ’00s. The shop carried all kinds of specialty items to cater to the talented sculptors, painters, and model builders and the studios they worked for.

I was making crude castings with dental alginate in my bedroom in my teens, and pouring polyester resin in the garage. My parents let me turn my room into a giant installation piece where I would staple fabrics to the ceiling, glue found objects to the walls, and weave wires and cords between the bars of my bed frame. My dad would bring me home the damaged merchandise from the shop and I would build costumes and sculptures with half-dried clay, broken model kits and exploded tubes of acrylic paint.

I started getting portrait photography work around the time I was 23, and was able to get just enough commission work to support myself in a tiny apartment in downtown LA. From there, I was able to gradually move into a studio space where I would started constructing sets for my portrait photographs. I wanted to incorporate what I learned while working at the hobby shop (making molds, sculpting, model building, painting) into my photography, so I started taking molds of the portrait subjects and building those elements into the pictures. The work naturally evolved into sculpture from the heavy costuming and set building I was doing for my photographs.

Did you consider that work to be more set design or fine art?

My lack of academic credentials and reluctance to follow the standard art world protocol has me feeling like an art-world outsider. I get so much love and support from the general public, however, that I feel my work has value and importance regardless of being accepted in elite circles.

Do you think the lack of formal, classical art training has allowed you to be a little bit more free in what you do? It’s like you learned from just being around the film industry.

While people were in school learning to make artwork that was tailored to integrate into the gallery system, I was making work to integrate into my own social media channels. Presenting my work was just as important as the work itself. Lighting, set design, and ephemeral elements all became part of the artwork in order to present it as a documentation of the physical objects I was making. But because of this platform, the documentation became more important than the physical pieces, which were discarded or cut up and turned into new objects to be documented. This approach has completely informed the artistic decisions I’ve made. Both the potential and limitations of the social media outlets I was using were integral parts in the process.

I assume the Channel Zero project came up through social media? Was this your first time working for a formal TV production?

Nick Acosta, the showrunner for Channel Zero, approached me about being a creative auteur for his TV show. I had never worked on a show, but they promised freedom to create my own concepts, so I jumped for it and I absolutely loved working on it. I learned so much. I would love to work on another film project, and in fact, I would love to direct a film project someday.

Was there a big change in the way you worked when it came to a TV production?

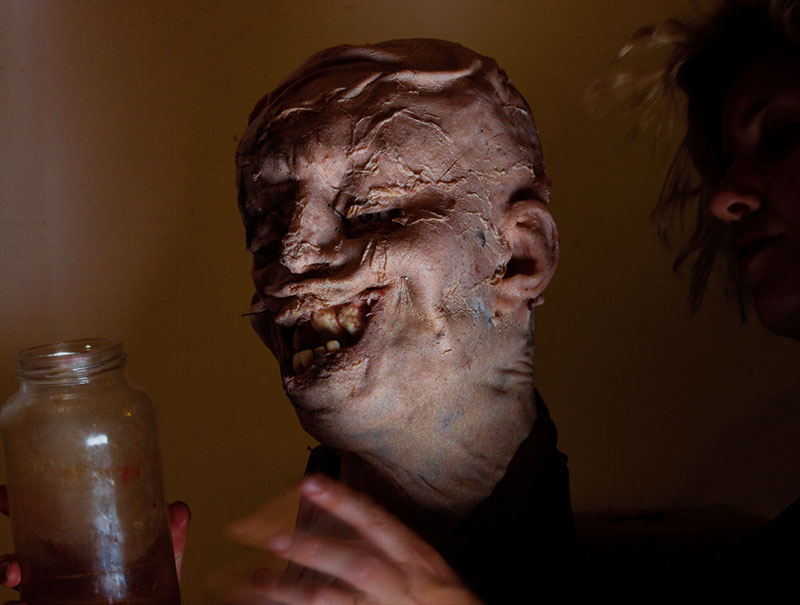

The biggest change was working with assistants and money. It was wonderful! I had people picking up my supplies, filing my receipts, organizing my materials for me and cleaning the shop every night. I still got to make the work myself, but my crew were the extra hands I wished I had all my life. The hardest part was surrendering control over how my work was lit and the angles it was shot from. Outside of working on Channel Zero, it’s pretty much me working alone to make everything— from the molds, to the structural work, to the final hairs punched into a piece. I do it all myself.

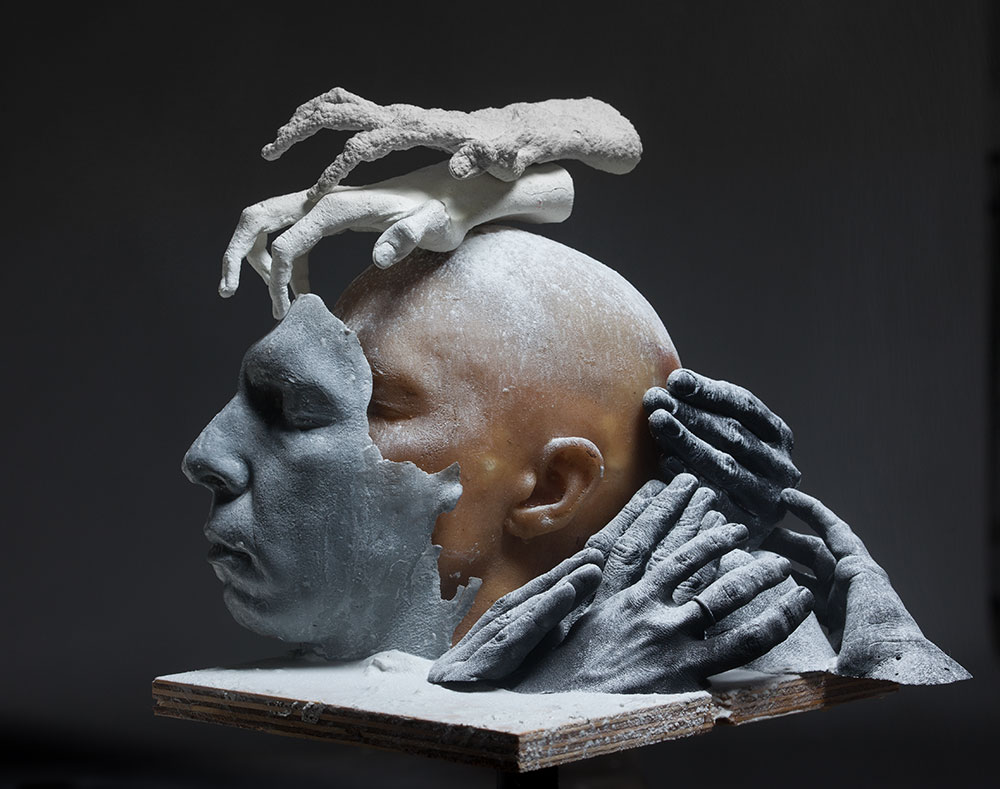

There is obviously this element of horror and the grotesque in your work, but there is also just the sheer skill of presenting almost hyperreal, alternative realities. How do you balance these two elements?

Experience as a human being is horrifying to me, and that is reflected onto the things I make. Honestly, most of the time, I don’t even realize something is creepy until people give me feedback. I usually think I’m creating intense visual metaphors or transcribing my experience.

So, I just gave you feedback? In that vein, what is the best thing someone has said about your work when they have walked into one of your gallery shows or commented on your social media feeds?

This girl who made a hand-knitted version of one of my masks brought it to my art show last year and gave it to me. She’s a dentist by profession, and I have always wanted to be a dental technician. We stay in touch and send pictures to each other of surgical tools and interesting medical devices. I am just as fascinated with her work as she seems to be with mine. I’m excited by how artwork tends to be a magnet drawing together people with similar interests. I love that my work has attracted all these people into my life and weaved us together with a common thread, even though often we do completely different things.

(sarah sitkin in her studio)

Sarah as a 10-year-old: what was your favorite movie, TV show, and book?

Honestly my life didn’t even start until I hit puberty. At 10, I was probably into whatever my parents wanted me to be into.

Okay, Sarah Sitkin now: what are the things that are influencing you?

The natural world has my attention. I was really into technology, engineering and digital realities for most of my adult life, but in this past year, I have really been interested in what is tangible, and how it came to be that way. I love understanding how changing environments brought different biology and behaviors. I am also fascinated by human psychology, behavioral patterns and coping mechanisms. Learning is the biggest catalyst for creativity in my life. I love researching.

What are you working on next?

I am working on a solo art show, Insecurity Blanket, which is focused on wearable pieces. I’m making skin suits, prosthetics, and non-invasive body modification pieces. The context of the skin suits is the concept of the art carrying the "burden" of the bodies. For example, some, not all of the wearable pieces, will be made with the intention that they are interactive and show the participant what it feels like to be in that particular body, and the stresses of it.

This article was originally published in the print edition of Juxtapoz Winter 2018 Quarterly

@sarahsitkin