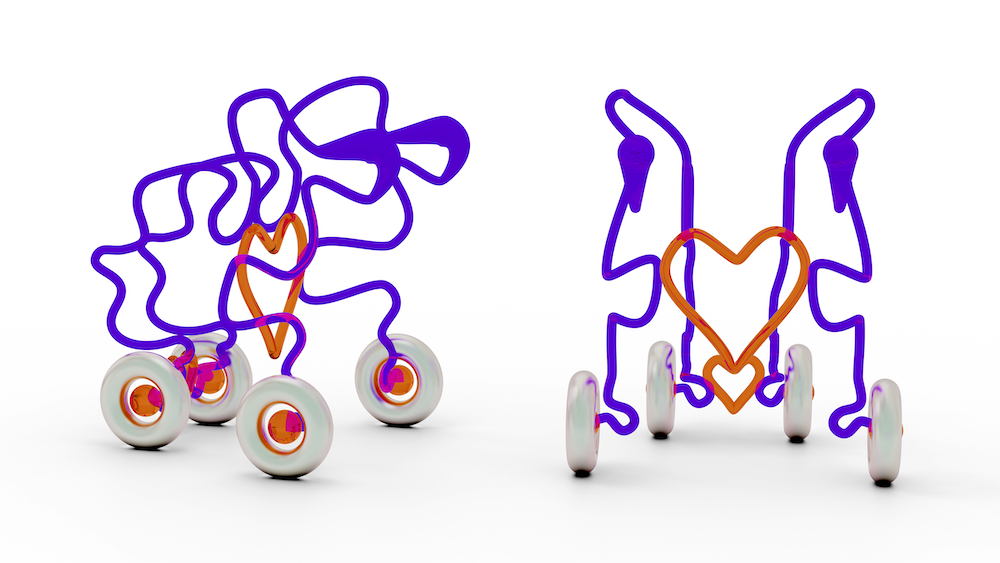

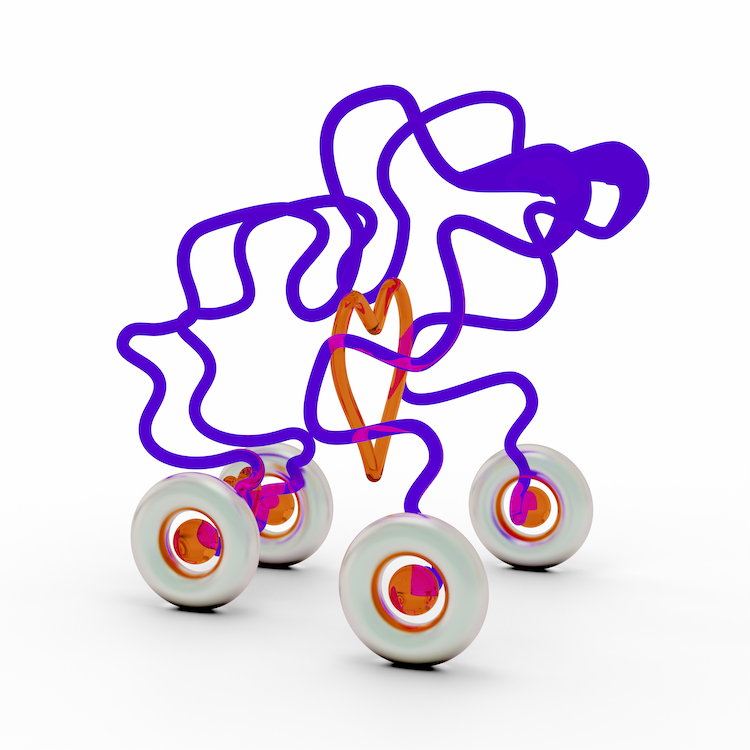

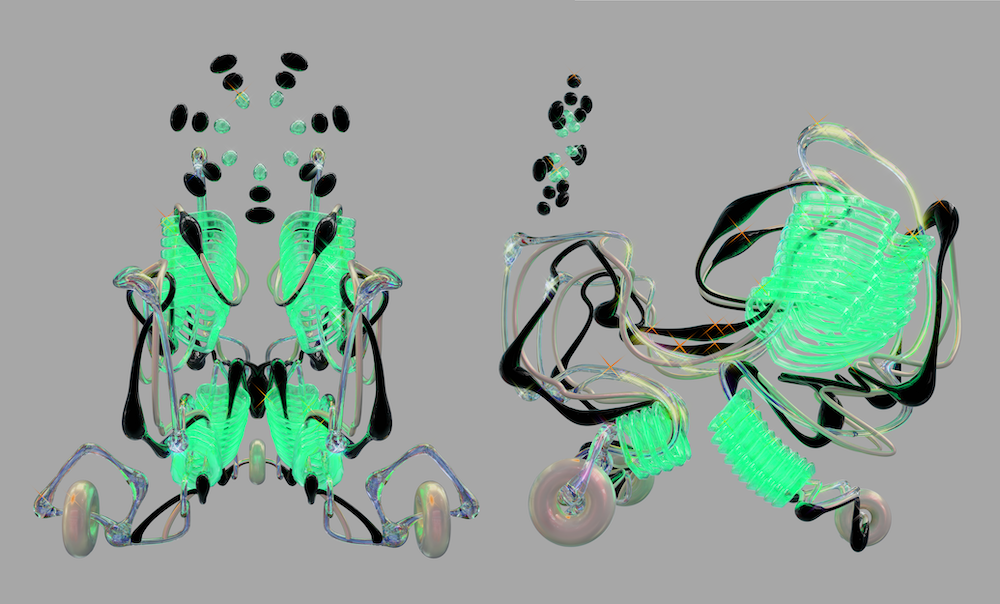

Ableism abounds in a world built for those who move normatively, but a wizard like Natalee Decker is rare—one who actively redesigns ideas about movement and access, mobilizing activism through artful fantasy. Their work tessellates beyond our spare reality and galvanizes the uniqueness of being. Reimagining everyday objects with more bodily harmony, the artist’s creations are painterly and seemingly sci-fi, radiating an essence of worldbuilding ideals.

Kristin Farr: Why did you start imagining these fantastical, sinewy designs?

Natalee Decker: I’ve been making the fantasy mobility devices as both personal therapeutic exercise, and to counter perspectives of disability that are rooted in ableism and hetero-normativity. I avoid getting into my disability origin story because disabled people deserve privacy and trust, and I equally try to avoid contributing to any pity or inspirational dual narrative that narrows public perceptions. But I will say that my life was abruptly and dramatically impacted by an acquired disability.

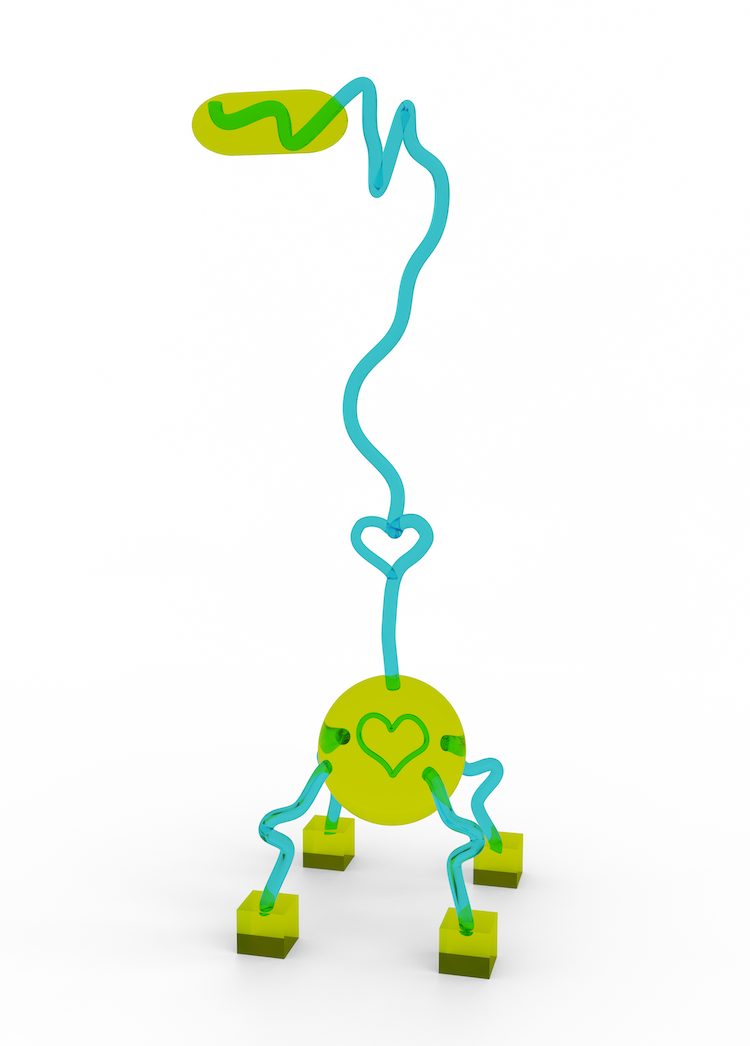

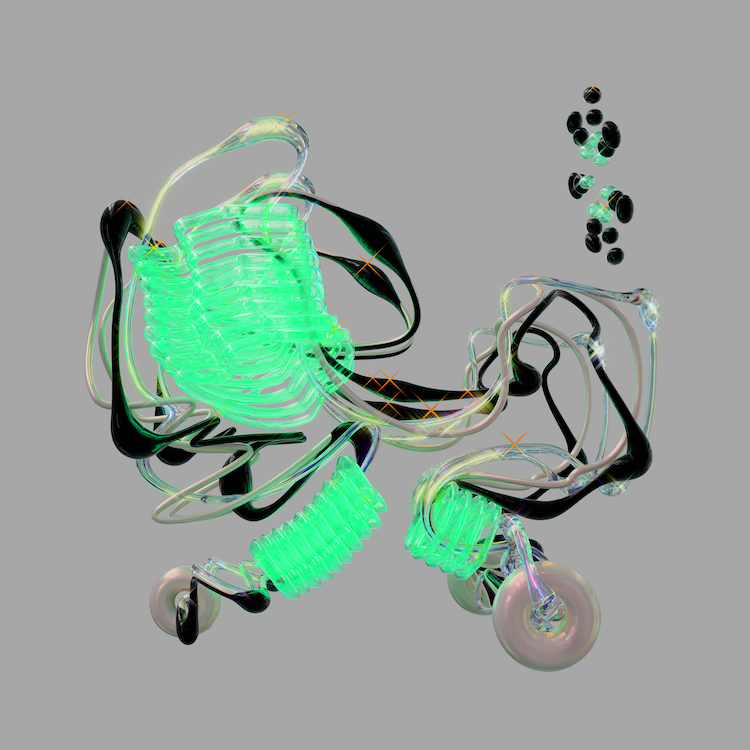

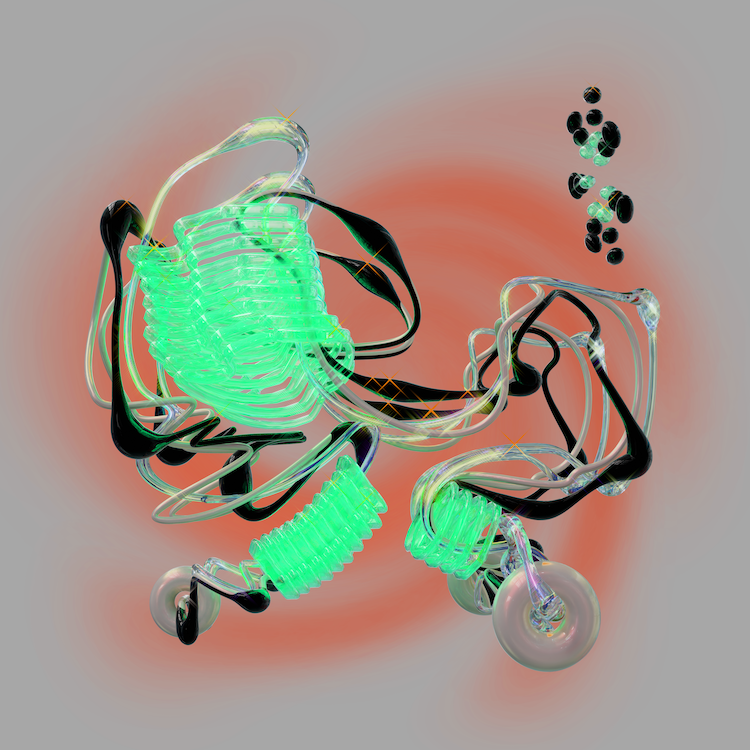

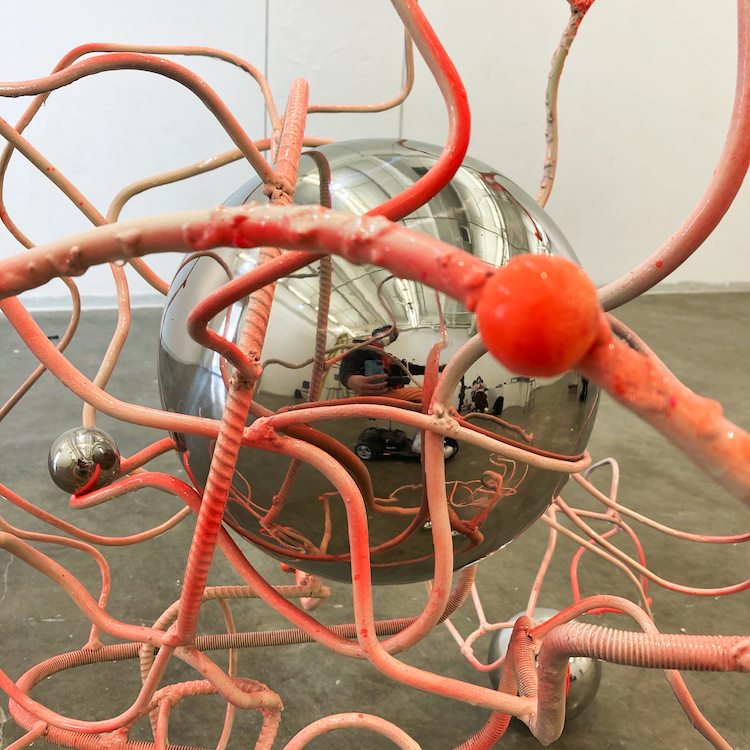

As much as surgery, medications and medical devices saved my life, my art makes me want to survive. It's become this vital medium to process loss and trauma that happens at once and chronically. The designs are a response to the real world devices—canes, scooters, wheelchairs, walkers—I use each day, antagonizing the sterile, medical, and stigma-laden auras which surround the objects. I intentionally re-imagine them as a sort of extension of my body, with fluid impractical forms, vivid celebratory colors, and questions about desirability. The devices allow for some sort of mobility of ideas and feelings, as an exercise in imagining a more liberated disabled existence. The sinewy-ness has a direct relationship to the organization of the nervous system, organic meeting industrial rigidity, and the fluidity of the body. The curves dull some of the sharpness of certain memories or my regular collision with the sharp edges of the infrastructures of ableism.

How do you describe your work?

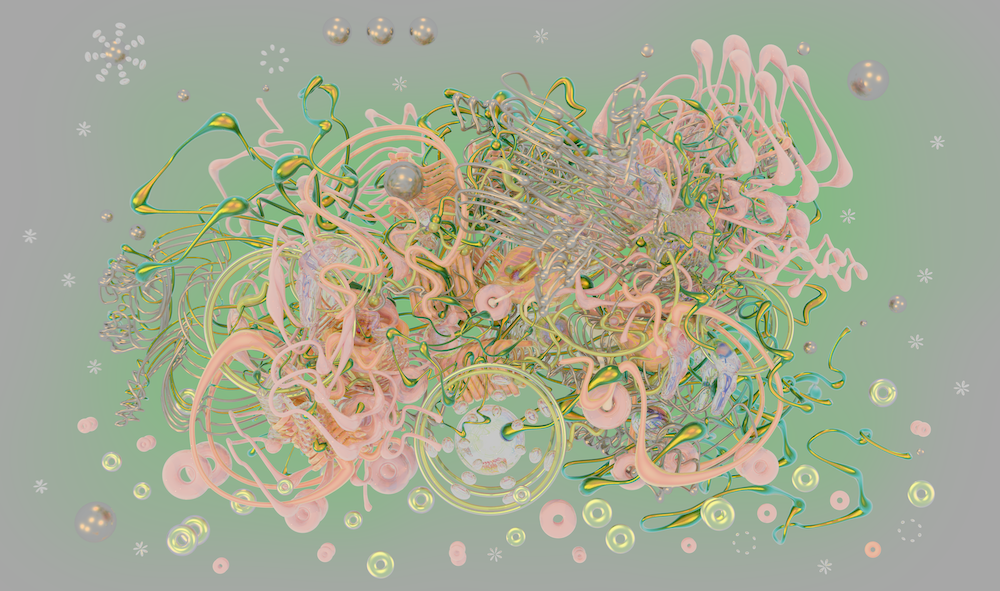

I’m committed to making work that is deeply personal and it all connects to my obsession with figuring out my own experience. I’m probably trying to expose myself so I feel less lonely, since being disabled can be such an utterly isolating experience. I share myself and seek connection in return. I’ve employed a variety of mediums including 3D CG, animation, sculpture, painting, photography, and music to parse out things like disability aesthetics, technology, crip fantasy, memories and queerness. I love computers. I’m a nerd. I should work on going outside more, but I really love making work.

For me, art is not just about some sort of monetizable production, but also about the ways we live—about creatively re-imagining how we exist in this world together and solve problems. When I was newly disabled in the hospital, the staff kept assuring me of my citizenship in this very hetero-normative future without actually asking me if that was what I wanted—telling me I would still be able to have children, that I could live totally independently, that I should get into adaptive sports. I needed to create something different for myself, and art has allowed me to envision and create my own crip future. Art is also a potent tool for encouraging other people to consider and care about experiences they have not personally lived, and disabled people desperately need more collective care.

Can your designs be manifested as reality?

I’ve recently started creating the designs as sculpture. I’d love to have some weird fashion mobility aids to use in my day to day. But there is a big difference between these devices existing in real life as functional design objects versus as speculative fiction. I’m interested in the tensions of creating an abstract, functionally practically useless tool which is conventionally supposed to be very rigid and ergonomic as a matter of necessity. It becomes especially ironic within the context in which mobility devices can be incredibly expensive and difficult to access despite their cruciality. I utilize an investigative and experimentational capacity to try and highlight issues of access and disability perceptions.

I would absolutely love for there to be more aestheticized practical mobility devices available in the world. But what is so much more important is that we, as a society, address the unmet basic needs of disabled people: the ways so many of us can’t get into certain buildings no matter what our mobility aids look like, the lack of access to quality healthcare, housing, employment, the disparaging stigmas. A nice looking wheelchair won’t solve these problems and might even distract from them, but I hope that my work can effectively draw attention to this much more urgent work of creating basic social equity for disabled people.

Tell me about your most visited color palette—is it specifically inspired?

I pick colors I feel drawn to intuitively. I want vibrancy and go for a lot of neons and pastels. I love how computer screens can give colors a uniquely bright illuminated quality. And CG software uses complex math and coding to simulate how light interacts with different materials so you can create these really dynamic and emissive colors that might not be able to even exist in reality. It’s amazing how variable light can create such distinct sensations in our body, hold so much varied cultural significance, and combine to create whole new feelings or connotations.

Describe your ideal party.

There have been very few parties in my pandemic and I really miss them. Ideally, I wouldn’t have to think about access first. I so appreciate anyone who is putting in the work to make queer nightlife accessible—hosting events in accessible spaces, putting access info on flyers, etc. Beyond that, I’m always wanting a water baby moment; give me a glass of champagne and someone to talk to in a hot tub, hot spring, under a waterfall, in some blue grotto.

You are a fashion icon to me. Tell me about your personal style.

Thank you! How flattering. Fashion has such an incredible power to make you feel good in your body and that’s especially important when you feel like your body is undesirable. As much as I try to use fashion to celebrate my body, I know I also use it to conceal or compensate as an extension of my own internalized ableism. That is the dark side I am working through, but I feel like it deserves honesty. Mostly, I just try to have fun with fashion, using clothes as another form of creativity, whimsy, and gendered expression. I love to thrift and wear pieces my friends have made or screen printed. I’m still working through the heartbreak that I can no longer functionally wear hot platform shoes, heels, sandals, etc. I had a really hard time getting rid of my old shoes, and I’ve kept a few of my favorite pairs in the back of my closet as these grief objects I need to turn into an art piece or ritualistically discard. I’ve had to get more into really sturdy sneakers and boots, but that’s OK because I’ve been leaning more butch lately anyways.

How do you hope people feel when they interact with your work?

I want disabled people or anyone navigating some kind of marginality to feel seen and assured that they deserve space in this world, in the arts, in dynamics of care. As much as my work is for me, I hope for an impact—that the work can contribute to larger conversations and narratives happening about disability and liberation and justice more generally.

@Crip_Fantasy // This article was originally published in the Summer 2022 Quarterly