Lucia Hierro

Fuck Up the Algorithm

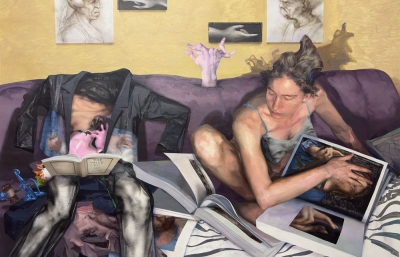

Interview by Kristin Farr // Portrait by Laura June Kirsch

A lone plastic shopping bag, plucked by the breeze, floats gracefully down the street. It is the “muse” of Lucia Hierro, who, although foremost an academic, is also a conceptual artist—a driver of dialogue. Her work does not serve light snacks. It divulges the dark twists of labor and production; the juxtapositions and contradictions of late capitalism.

In developing her latest museum show, Hierro didn’t play it safe—she tried something risky and monumental. In the meantime, she also successfully fucked up the search-term algorithm for postmodern masters of installation art. Subtle references to other artists’ concepts are less revealing than her broader mission to educate by dominating space and leveling up with each of her singular, complex and curious creations.

Kristin Farr: What’s been going on this year?

Lucia Hierro: I did some work for David Klein Gallery in Detroit, and an install for Museo del Barrio’s Triennale, and they both opened the same day last spring.

I was at the Red Bull artist residency in Detroit for three months, and I had friends who introduced me to Detroit in this really beautiful way, and I have a really deep connection to the city. The show at David Klein was the first time some people had seen my kind of work in a gallery; this strange, digital mural-looking thing with sculptures. They had a lot of foot traffic, which was odd, given covid. A lot more people were stepping into the gallery who didn’t feel comfortable doing so before. My big green wall in the back of the gallery drew people in.

Then I had this Museo del Barrio opening, and it’s a really interesting thing to hear people say they’ve never been there, and that the articles surrounding the show have this level of condescension, like they’re patting us on the heads, “Look at the cute Latinos having a little show.” A lot of the artists have been working in obscurity for decades, along with younger artists, and when you have been working that way for so long, you’re not making work that is easily reduced to a headline. I thought the Trienialle was doomed to be seen as something it wasn’t, and Museo del Barrio’s been working so hard to revamp that image. I think they finally scratched the surface of doing the work they were supposed to be doing all these years. So, in that way, that show is an incredible teaching tool.

It’s been interesting to see how the work lives in these different contexts, and now I’m working on my show for the Aldrich Museum; I’m in the throes of finalizing all the little details. Everything is being delivered right now, so I’ve been losing sleep over that! It’s been interesting to work on all these things at once.

And for different audiences. Tell me about The Gates.

The exhibition is called Marginal Costs, and I’m making a new series of sculptures called The Gates. It does draw a tiny connection to Jeanne-Claude and Christo because they did their Gates project in Central Park, all across the city. The debate about it, at the time, was really interesting. They spent so much time working with the city; and, in the documentary, they almost glossed over the conversations of how far into Central Park their Gates should go. And Christo and Jeanne-Claude would say, “What do you mean? The whole park. Everywhere.” And other people would say, “Are you sure? There’s an area where they might not work…” It was the coded language of saying—”I don’t know if you want to put your Gates in El Barrio.”

I remember being in high school, telling a friend I’d love to walk all the way to downtown through the park to see them, and we did this really beautiful tour. I had been wanting to work on my own Gates for years. It was two ex-boyfriends ago when I had the idea, so I reached out to one of them, like, “Hey, remember The Gates? I’m finally making them!”

They’re basically just wrought-iron gates you’d see outside someone’s home. They’re based on photos that I took in the neighborhood, but they’re actually made out of iron and three times the size. They’re seven or eight feet tall. I went to my uncle, who owns a gate business in New Jersey, and decided his company would be the fabricator. At first he said, “No. I’m not doing this.”

Why?

He didn’t understand it and when I told him the museum was in Connecticut, he said he couldn’t make gates outside the state of New Jersey because of insurance purposes and liability. I didn’t have the heart to tell the museum he said no, so I kept it to myself and thought I would convince him.

I remember Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Umbrellas in California when I was a kid. The Gates were like an East Coast counterpart, a decade later, so the regional context is notable.

The visual aspect of mine won’t be anything like Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s, but I think the title would make anyone in the art world think of them. It’s the same way I did the chip racks—I talked about Judd in a lot of interviews when my chip racks came up.

I read that, and was surprised at the connection, until I thought of his stacks.

My friends were googling to pull images for lectures, and they said I would come up when they searched Judd. They said I fucked up the algorithm for Judd, and I was like, “Oh shit, I should do that more. I should title my pieces in a way that will get into other artists’ algorithms. I called these new pieces The Gates because of that. There are three of them, and I’m testing out an idea on this museum show. Most people will want to show their signature hits, but I wanted to do something completely different and see how that works out.

There will still be the usual suspect artworks, because they’re borrowing from collectors, so I’ll have a lot of my grocery bags, and I made a few new ones. There will be a really large mural on a 30-foot wall, and it’s going to have a bit of the neighborhood in it. There’s an interesting full-circle thing, thinking about the outdoor space and architectural vernacular of a neighborhood.

Once covid hit, I feel like it all took a slight pivot, and that I started to understand the show differently. I was looking at The Gates and thought, oh man, there’s definitely an odd spiritual connotation, like heaven’s gates. It’s also funny with the placement of where they’ll be in the gallery, like the white side of the museum versus the mural side, which made me think about ideas of gatekeeping.

There will be these fabric mailers stuffed through the gates. Around here, people run around with those little coupon books called circulars. They roll them up and stuff them in fences, and they just turn yellow and get soggy outside. No one really cares about these circulars, but I always look at them; it’s an interesting way to think about our shopping and the passage of time.

Also, in so many of these homes, in the middle of Fort Greene in Brooklyn, no one cares that Land O’ Lakes is a few cents less this week. They’re just gonna go get their freakin’ Land O’ Lakes. I was thinking of the luxury of not having to count your pennies, and how everything about covid heightened the things I was already looking at in the work. It made everything a little bit more pressing to get out there.

So, I’m excited about The Gates, and my uncle came around. When he put extra bars in one of the gates, I said, “No, follow my drawing.” And I had to explain how it’s not supposed to be functional, and he objected, “But a person could fit through there!”

Finally, this one guy, a very Dominican dude, goes, “Oh, sí, es un simulacra.” And there’s a word you only hear in art school. It was really great. I said, “Yes, what he said! It’s a simulacrum. It’s acting as the thing, it’s just larger-scale.” So they finally did it and it was really nice to work with them.

Amanda Uribe from Latchkey Gallery is part of the reason I got this show, and she was blown away by the size of The Gates. We were talking about how my family’s involved in making them. The people I work with in my studio are all specifically chosen collaborators. From my printers, to the guy who does some upholstery for some of my sculptures, they’re all collaborators in the work that I make, so it also functions like this little economy.

We have this Dominican group of people that my uncle brought over to work with him. He got a job making gates in the early ’80s, and he learned Italian first, and English second, because the guys who owned the shop were Italian. Later, when he opened his own place, he named it Luigi’s Iron Works. His name is Luis. So, you know… people know Italians to be really good at doing this masonry work, so he was smart and hustled. Nobody wants Dominicans making their gates. And that’s the type of hacking we’ve been known for.

This show title, Marginal Costs refers to the economics term. It’s not so much taking it out of context, but actually speaking to the politics behind economic jargon, which is a way to hide the real meaning: there are marginal costs—to people. There are people behind this. Everything you do has an effect on someone else, and I’m showing in Ridgefield, Connecticut, which happens to be where many of the people who work in these finance industries have their big old homes behind their big old gates.

I really wanted to focus on what the work is about. I feel that there’s a lot of skirting around it, like it’s about the culture, but I’m always, like, no—it’s about economies. That’s really what it’s about: The way we live our lives in this sea of uncertainty and debt, where we continue to talk about our individual identities, when, in fact, these larger systems and structures are talked about theoretically—but never in terms of their direct impact on us, or the fact that so much of our culture is manufactured and branded.

The museum looks quite posh and also like a dream space to show.

I was worried about my sculptures being too heavy and tall, and they assured me, “No, you’re good. We’ve had KAWS sculptures and huge Frank Stellas in here.” Half the museum opens up so you can bring in giant sculptures.

Like, “Don’t worry. Men have dragged bigger things inside.”

I always wanted to stay away from metal and hard sculptures because I felt for so long that, in order to become a very successful female artist, you had to use the forms that men were very successful at using. If men work with giant metal-bending sculptures, and you’re a woman who happens to do that now, that’s very cool. If you’re making soft sculptural objects and whatnot, people are like, “Oh, OK, like Faith Ringgold.” And you know how she was treated.

I attended a lecture where she talked about being pigeonholed as a crafter.

I always had a hand in this industry for the love of it, and moving the conversation forward in any way I can, which is why I was an academic first and an artist second. I knew the work was a vehicle to drive certain conversations that move things forward. I was never interested in status, or making pretty paintings of Dominican people. I see the function of that, politically, as a tool, but I didn’t feel that would be enough for me. That song-and-dance could also come back to bite you.

When you use a material that’s familiar but not used in a familiar way, what does that do to the viewer? A lot of people don’t know my works are made of fabric because that’s not a reference people know—photo-based objects in a large scale throw them off enough that they’re interested in the object as is, and then they start getting into the process of how it was made. Pop Art is really interesting in that way, because the reference point is so close that everybody feels an ownership over it. As a maker, I sort of disappear in that. I notice people can feel like that object just always existed in that way, because it exists in real life, and you see it every day; but, in fact, it took me a lot of engineering to make that stupid chip rack and get it to function .

Your sculpture, Can I Borrow a Cup of Sugar, a giant Domino sugar bag, references a friendly neighborly trope, but also about the shady production loop of the industry. Is it a burden to have to explain the deeper layers of meaning?

You noticed something that a lot of folks didn’t, but I think folks who follow the work see the ways in which it is tilting. People who equate my work to a conceptual practice will understand that every aspect is a choice.

That piece was collected by the Perez Art Museum, and before they collect things, they ask a lot of questions. They asked me, “How do you see this piece in the context of Kara Walker’s work?” And one, I would never compare a bag full of packing peanuts to her work at all, because the labor and everything behind that… it could be a slap in the face to the production itself. Kara’s work is mesmerizing and, in a way, can take away from the actual way we will continue to use the thing. If I had a nickel for every Goya can that I saw in somebody’s bodega bag, even though Goya came out in support of every racist agenda with Trump, we'll still buy it. I’ll admit it, I still bought it! Damn, I needed those black beans. What the fuck is wrong with me?

It’s like that joke, “Oh, you’re an Atheist? What day is it?” We’re a little more Christian than we think. I love that we’re so entrenched in things. When people talk about my work as Dominican—yes, that’s my lived experience, and I can only see things through this body, but there’s no answer to what really makes a Dominican. My father’s a musician and composer, and his friends are ethnomusicologists, and we understand that appropriation can only really go back to people like Elvis, and power-stealing music from people. In reality, Spaniards own the sixth string on the guitar. They invented that. But only the sixth string. The rest of it has a longer history.

Growing up in a house where you understand that, globally, this music has had a life, and that’s why rhythm is what it is, it’s hard to say, “This is very Dominican,” because that’s not how the world works. We don’t live in a vacuum. We’re all connected.

Now is definitely the time to talk about economies and late capitalism in general. Through talking about our lived experiences with a friend, I learned that his family’s in Miami, near Little Haiti, and that’s the sugar they use—Domino sugar. It’s so wild how they completely understand their own history and the ongoing slavery with the Dominican Republic when it comes to manufacturing all this stuff, but they’re still a Haitian family in Miami, and that’s what they buy. That’s what they know. I’m fascinated with that relationship and I want to continue to sort of capture that awkward rub.

Lucia Hierro’s exhibition, Marginal Costs, at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, will be on view June 7, 2021–January 2, 2022.