The mundane or everyday moments of our lives are often overlooked until they are lost. Whether it’s an abrupt clean break from a previous way or life or something gradual and unnoticed, there is grief in losing something we experienced habitually—cooking, folding laundry, taking a walk as only a few examples. Often, it isn’t until it’s gone that this thing that was previously framed as tedious is now something to cherish, to hold dear.

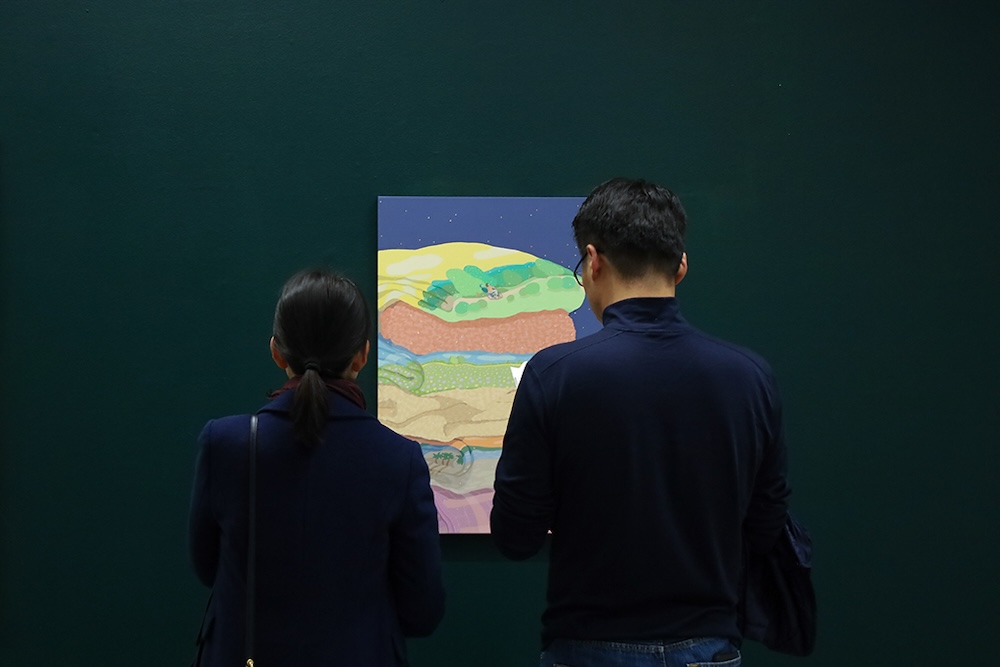

The magic of the everyday isn’t lost on Seoul-based painter Danym Kwon. Her pastel-colored paintings depict serene scenes of leisure and respite, inspiring us to find gratitude, rest, and happiness inside seemingly mundane or repetitive moments. Prior to the opening of her solo exhibition A Soft Day at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco, Kwon spoke with the gallery’s Katherine Hamilton about what she finds inspiring and how she stays optimistic even in moments of isolation.

Katherine Hamilton: A large influence on your paintings and decision to work in a “softer” style was your cancer diagnosis and your road trip around the United States. Can you describe the very first types of works you painted and how your style has evolved since then?

Danym Kwon: Rather than a methodological change, I would say the subjects I deal with have shifted. In my twenties, I tried to reflect our society through my art by painting images found in the latest news or by visiting someone's home and painting the objects I found there.

When I returned to painting after a long hiatus, there was a significant change in my identity. I was now a mother of two children, an immigrant, and a cancer survivor. For a period during my cancer treatment, I was unable to care for my little baby. I began to miss and cherish the time I had taken for granted—I longed for daily chores like pushing a stroller for my baby or preparing meals for the kids. The beautiful nature and pastoral landscapes I saw while living in America brought me much comfort. Particularly, the small, modest houses set in vast fields or nestled in the mountains reminded me of my family. The vibrant trees and flowers I saw on my walks gave me great comfort and strength. These life changes and experiences naturally became the new subjects of my paintings.

How did you land on your unique, illustrative style?

In my teens during the 90s, the motion graphics introducing the MTV channel really captured my attention. This influenced me to study both visual design and fine arts in college, where my artwork style evolved. The simple background space and surrealistic expressions in my work are influenced by traditional Korean painting. In the art high school I attended, each student had their own major, and I chose to study Korean painting. Traditional Korean folk paintings and Chaekgado (Korean still-life paintings) often feature objects like vases or books alongside landscapes from entirely different dimensions. The empty backgrounds in Korean paintings can extend into infinite dimensional spaces.

Mentioning MTV and traditional Korean painting together might seem unusual. I guess the uniqueness of my work arises from the combination of these two disparate elements.

Much of your work deals with personal transformation through hardship, and the perspective gained on the other side of it. Do you see your work as a type of therapy that helps you (and others) through difficult times, or more a report of your own emotional transformation after the fact?

My work can be described as a report of precious moments that provided me with comfort or poetic inspiration. However, these scenes are not exclusively personal or unique to me. They include universal experiences like encountering wildflowers on a walk, the afternoon sunlight, trips to somewhere new, and time spent with loved ones on weekends. I believe viewers can find their own stories within my paintings because of the relatability of these moments.

Yes, I revisit and find solace in cherished moments by bringing them out of my memory and onto the canvas.

Often in your work, bowls, vases, piles of laundry, and other things that remind us of home contain external scenes, like a portal to another world. I think about my own experience folding laundry and daydreaming about being somewhere else. Is there an element of escapism or daydreaming in these pastoral scenes, or more about memory?

While based on memories, my art takes on a surrealistic expression as the feelings I experienced in those moments or scenes are added, making it dreamlike. Bowls, vases, or laundry piles can serve as both an escapist gateway, transporting me through these memories, and conversely, become a medium that brings these memories close, allowing me to possess them intimately.

I know you often use these soft colors in your work to inspire viewers to find happiness in everyday moments, but I’m also wondering about “hope” in your work. What does “hope” mean to you, and how do you fold it not only into your paintings but into your artistic practice?

To me, hope means discovering the love that is undoubtedly present in and around me at this moment. Ultimately, it's about conveying a message of love. For example, I've heard the trees and flowers speak to me while on walks, saying things like “It's okay. We're here for you, we love you.” I record these moments in writing or simple drawings and then use them as inspiration.

Speaking of “hope,” what’s a dream project you hope to realize one day in the future?

A project I'd like to try at this moment involves working on a large-scale piece with ample time. Also, the idea of staying at a certain location and creating site-specific works based on the stories I discover there.

Back in 2018, you participated in an exhibition about artist mothers. Artists don’t always acknowledge their parental roles in their practice. If they do, they must also acknowledge it’s a relatively taboo subject (I think of Lenka Clayton and her series of works regarding her relationship to her son as a mother, specifically). What did you learn from being exhibited with other artist-moms?The exhibition Artist Mom wasn't specifically about the theme of motherhood. It was organized by a non-profit organization called Simple Steps that helps women whose careers were interrupted due to immigration. Through the exhibition, I was able to reaffirm my identity as an artist and connect with others in similar situations.

Immigration presents challenges like language barriers and holding on to your identity. For example, when I was in Korea, even when I was not working for a while, I still lived with an awareness of myself as an artist—I was a part of the artistic community and I frequented galleries I had worked with. However, after coming to the United States, it was not easy for me to recognize myself as an artist because those aspects were missing in my new environment. It's not easy to integrate without any connections to American society, even if one has professional experience in a certain field from their past. This sense of exclusion is even more pronounced for parents raising young children.

Your domestic scenes might also be associated with traditional notions of motherhood—taking care of the house through chores and decoration. Would you say motherhood has influenced your artistic practice, or do you keep your work separate from your parental role?

My work is closely connected to these aspects, but I am neither particularly fond of housework and home decoration, nor do I align with the traditional image of motherhood. However, stories about my family and children can be found in many parts of my work, as they are the ones to whom I devote most of my heart. The experiences of spending time with and lovingly observing my loved ones are integrated into my work. My day can be described as swapping my studio apron for a kitchen apron. Everything is mixed and interconnected.

Finally, since your work deals so much with optimism and finding warmth, especially during or after hardships, what’s the most difficult thing about being optimistic? What’s the easiest?

The most difficult thing: Yearning for what I don't have. The easiest thing: Looking at the present moment with affection and fully experiencing it.

A Soft Day is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco through January 27th. Installation photos were taken by Shaun Roberts and opening night photos were taken by Kuan Ya Wu.