“Precipice Don’t lose your footing The wall might be a floor”

I type this list into my Notes app as I visit Lily Wong’s studio. In her work, she plays with the tenses and outlines of narrative. There is a flexibility here. A reliable narrator is not to be found. The older you get, the less sure you are of your fixed personhood. How open can you leave a story? One piece in particular, Moonflower, contends with all of this. The main figure is not simply mirrored but divided into three. Scale is thrown into question by the small (?) figure in the distance, holding the stem of a giant (?) flower, the bloom of which enters the room along with the main figure. Her foot is entangled in another stem, and she seems to be taking a step forward without solid grounding.

Lily’s studio is neat. Large sheets of paper are pinned to the walls, methodically layered with thin strokes of acrylic paint over weeks and months. Remnants of wiping off her brush or testing a color/mark surround the pieces like Seurat frames. These colors have become more complex than previous works. Much more interconnected, surprising colors often reflect onto other portions of the paintings.

References abound. A woodprint, Suzaku Gate Moon, from Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s 100 Aspects of the Moon; A small, oddball George Tooker, The Groping Hand; Bosch’s The Pedlar; stills from a Patty Chang performance video. These are images that are potent, Lily has kept these taped to her studio wall for years, or in spreads ready to be poured over in her library of art books, ruminating on them and allowing them to seep into her work and transform.

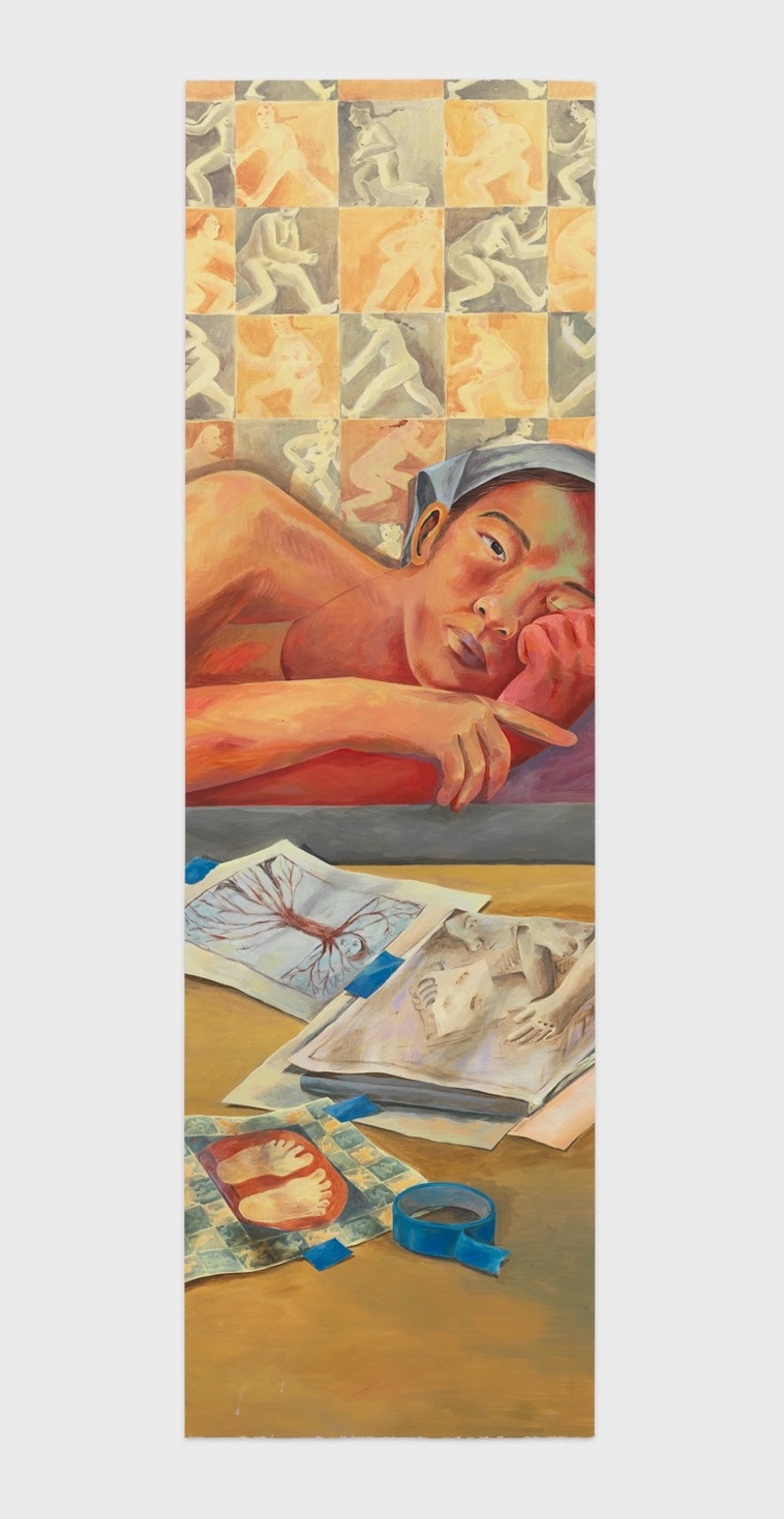

The Source is one of two paintings that not only point to outside artworks but consider that very action of pointing. Before the reclining artist, waiting to be taped to the wall with the recognizable blue artist tape, are prints of a Louise Bourgeois etching, one of Lily’s own works, and an artwork that was in the Met’s recent exhibition, Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet. This last reference is the most interesting as it inspired Wong to make the painting within the painting, on the wall behind the artist. There she renders her own versions of the gridded deities.

Time, as a symptom takes its title from a Joanna Newsom song, the last track on her 2015 album Divers. That particular album is a closed circuit, the last sound/syllable leads into the first, forever in a loop. Time is a dominant theme, both in the ways that it could exist beyond our understanding, spatially and dimensionally, as well as the weight that joy and terror place on our experience of it.

Two types of nostalgia are defined by Svetlana Boym in her 2001 study, “The Future of Nostalgia.” The latter is ‘reflective’ and here is where I believe Wong’s work is situated. Boym explains: “Reflective nostalgia thrives in algia, the longing itself, and delays the homecoming- wistfully, ironically, desperately. … Reflective nostalgia dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity.”

As Boym describes: “Reflective nostalgics see everywhere the imperfect mirror images of home, and try to cohabit with doubles and ghosts.” Sometimes Wong’s figures read as self-portraits, other times variants on a type. They split and haunt each other.

Like the reflective nostalgic, Wong “desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.” Here poses recur. Inside space is cavernous, outside constricted.

I guess cats and dogs exist in an ambivalent space as well: humans change them and they change us, but neither is fully domesticated to the other. There is always a push and a pull, a conflict. In Soliloquy the artist again arranges references, both with physical print-outs and drawings, as well as attending to the glow of her iPhone. She is crouched over in an impossible form (notice the spacial fuckery of her body in relation to the floor boards), with her cat, Louis, perched on her back. He seems to guide her, or at least anchor and ground her.

A dog nips at the figure's leg in Wayfarer, possibly attempting to stop her, either from leaving or from entering. The pose with dog is a reference to depictions of the pedlar figure, in a famous Bosch painting and other imagery of the time.

Ants that once populated Wong’s world return here, crawling at the end of the pedlar’s staff. Like the nostalgic that can never return home, the ants can return but they don’t necessarily mean the same thing. Once entering Wong’s older work to consume the rotting excesses of food, now they seemingly encourage the pedlar forward, even as the scrappy dog tries to prevent that movement. I think of other species’ sense of direction. That there are paths that aren’t comprehensible to us. Our proprioception is found lacking.

A braid suggests patience, and the making of a new form from the thousands of individual strands of hair on a given head.

In front of the extremely long, horizontal Time goes both ways, Wong spoke about the scroll as having a different temporality than other works of art. Not meant to be seen all at once, but rather in smaller sections the viewer would roll and search for, back and forth across the document. Despite showing the entire scene in her piece, Wong allows space and time to be inconsistent across the passage.

I am again reminded of Boym’s ideas of nostalgic imagery. She states: “A cinematic image of nostalgia is a double exposure, or a superimposition of two images-of home and abroad, past and present, dream and everyday life. The moment we try to force it into a single image, it breaks the frame or burns the surface.” I feel like Lily revels in the breaking of the frame. It’s not just a dream space, it’s too coherent for that. Maybe these are memory spaces, each time reconstructed by our mind. Each past altered by the present, each time.

Tooker’s The Groping Hand is reaching for something. The something isn’t legible and isn’t necessary to understand the painting. It’s about the reaching. The artist in Soliloquy is also reaching, across time and across images, trying to tap into a wavelength and transform. The rain clings to the window in pearly drops. Condensation longing to return to a deep body of water.

Iris Dement sings “I think I’ll let the mystery be.” Kate Bush sings “See those trees / Bend in the wind / I feel they've got a lot more sense than me / You see I try to resist… If I could learn to give like a rubberband/ I’d be back on my feet.”

Essay by Anthony Cudahy