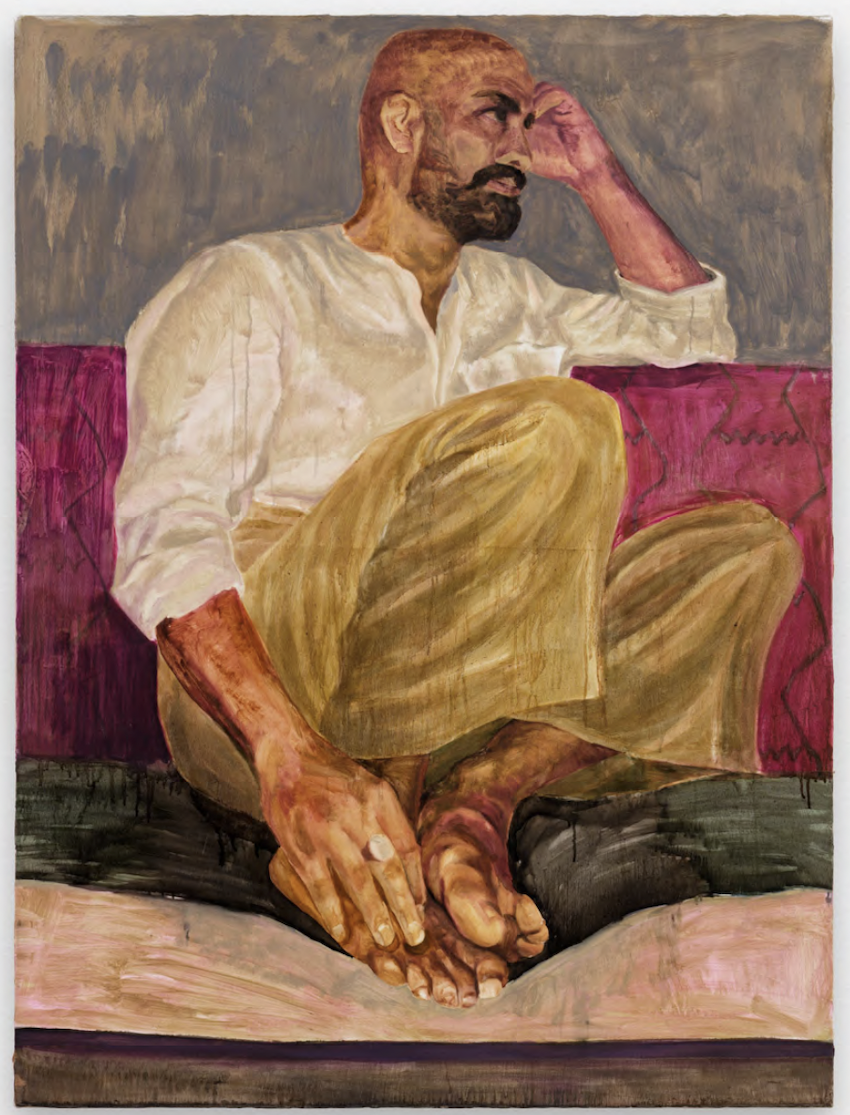

There’s something queer about Fiza Khatri’s latest paintings, and it’s not the people in them. While the artist in their work to date has already established a reputation for seemingly casual yet carefully executed portraits of friends and others in their social circle—many indeed gender non-normative—there has been a noticeable and growing de-emphasis on people. Indeed, what’s striking in the latest paintings is their focus, not on people, but on plants.

Paintings featuring plants in and of themselves are not unusual. Plenty of examples can be found in the history of art: flowers and fruits abound in still lives, while of course foliage can be found in landscapes, history paintings, and other scenes set in nature. In fact, in the French tradition, plants have been routinely deployed as part of painters’ compositional arsenal stretching from at least Poussin to Cézanne. In the latter’s Grandes Baigneuses (1906), for instance, the presence of the tall trees at either edge of the painting has the effect of keeping the eye on the motif of the female bathers. Known as repoussoir (from the French repousser, to push back), the term itself suggests the way that plants had become a convenient foil for framing and highlighting human subjects. In scenes in which both people and humans are present, the plants typically are thus of secondary interest. This pictorial order of things was in keeping with art’s traditional academic hierarchies, in which history painting, the representation of human activities, was deemed the highest art form, above still life and landscapes, and also the philosophical placement of the human subject at the center of the universe.

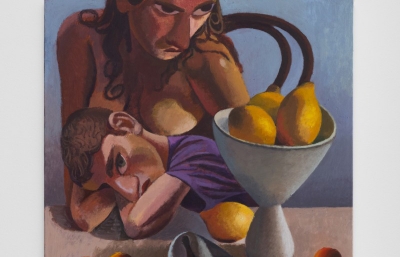

In Khatri’s works, however, the flora is no backdrop for the fauna; rather the opposite. These paintings work against the hierarchy visible in the tradition sketched above, and the roles that plants have played in art, and in human society—as decoration, as resource.1 Both Raag Multani and Duck Duck Cat, for instance, present houseplants prominently, alongside or even in front of the humans in them. At Other’s Edge pushes this strategy to an extreme, so that the pothos, aloe, monstera, and other green lifeforms form a jungle-like wall that must be visually navigated in order to reach the cat and two individuals visible in the distance.

In addition to being shunted off to the background, the individuals in At Other’s Edge also reveal little of themselves, as they seem to be asleep, or at the least in repose. Without exception in this group, the people, though the putative subjects of the paintings, have their attention occupied or otherwise engaged. This could be in listening to music, as the title of Raag Multani2 would suggest, or otherwise engaged or looking away. Turning Towards, Becoming a Room, or To Be Carried: the titles hint at states of being that are less about activity and consciousness. The net effect of the foregrounding of the plants and the deemphasis on the humans who are present is to heighten the plants as characters, as beings.

The redistribution of attention that Khatri’s paintings perform take as its point of departure the fundamental reevaluation of plant life that has been taking place in the last few decades, shifting away from perceptions of them as the most elementary of lifeforms, mainly capable of growth and decay. In contrast, researchers such as Suzanne Simard have unearthed compelling evidence demonstrating plants as possessed of sentience, or some kind of consciousness, and the ability to react to and interact with, their surroundings and the beings around them.3 In doing so, they reflect a broader shift in thinking to decenter human subjects, recontextualizing human presence as part of a larger, or more than human, world.

Khatri has noted elsewhere that for them, figurative painting is “not tasked with objective representation.”4 A simple way to understand the expression is that their practice is not a straightforward matter of painting from life; there is always a degree of invention, of “fiction and coding.” But invention, fiction, and coding are also aspects of world-making, of envisioning possibilities otherwise. In painting scenes in which the plants and mammalian life (both human and animal) co-exist as equals, Khatri’s work helps viewers to be able to see the more than human worlds in which we all exist. —John Tain

Fiza Khatri "The Beauty You Beheld" is on view at Semiose, Paris from January 11—March 15, 2025