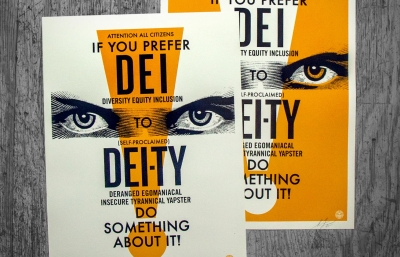

When Martyn Reed of the renowned Nuart Festival set the theme for this past Spring’s Nuart Aberdeen, “A Revolution of the Ordinary,” I had feelings of both elation and defeat. And to be honest, I wrote a rather ranting, mildly-disappointed-in-the-21st-Century-and-all-its-social-revolution-mechanisms essay about what I thought was supposed to be our controlled destiny of how we communicate with each other. Our ordinary lives were going to become extraordinary through new platforms of communication, public art, and the democratization of gatekeeper culture.

During the lead-up to Nuart Aberdeen, I found myself wondering just what is ordinary. I mean, hell, for the past 15 years or so, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have elevated each of us to extraordinary status such that “ordinary” is vaguely insulting. How dare you call my life or my experiences ordinary? I had brunch this morning on an antique wooden table, for crying out loud, and shared it with 51 strangers! But Nuart was clever, placing the word ordinary in the context of hyper-sensitive, perhaps over-educated, art history critics who have excluded nearly 99% of all people from enjoying what really is an incredible moment in art. There are so many good things happening! And not just Banksy, or Nuart, or JR. I’m talking about Kerry James Marshall, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Jonas Wood, Yoshitomo Nara, and Laura Owens, to name a few. Museums and galleries have such great shows right now, but many people have felt unwelcome because the culture was only made for those who read the right books, go to the right schools, and eat at the right restaurants, inferring that these gatekeepers are right, and the average people are wrong. So, ordinary isn’t so simple. It’s just everyday life. It’s waking up and going to work at 6:30 a.m. It’s eating your lunch on park bench. It’s going home at night knowing that perhaps you only have a few hours in your weekend to see the Walker Evans show at your local museum. “Ordinary” is finding ways to bring art into your life that is not dictated by the cultural elite.

The reason why the theme, “A Revolution of the Ordinary,” struck so closely, why I wanted to revisit it for this letter, is that I look at our cover story on OSGEMEOS and see how incredible their career has been, how original and on their terms. Anything but ordinary, it is entirely of their own doing, and outside of normal art structures. From the streets of São Paulo, with interests in graffiti and hip hop, they became some of the most famous and celebrated artists of this generation. Consider the burgeoning careers of Jeffrey Cheung, Oli Epp and KOAK, or the extraordinary stories of Fulton Washington and Know Hope, both completely different artists but employing unique voices in powerful, community-based ways. Even Rammellzee created a personal universe that has become not only a benchmark of Afrofuturism, but a blueprint for how an eccentric soul can be an art world all unto himself. So, consider ordinary, and realize we are building our own art history, our own narratives, just like 24 years ago when Robert Williams and friends started Juxtapoz. I look at how popular and influential this art generation has become, whether street or skate or politically motivated art, and it’s amazing how inordinately vital ordinary has become. —Evan Pricco