Thom Yorke and Stanley Donwood

The Kid A Mnesia Files

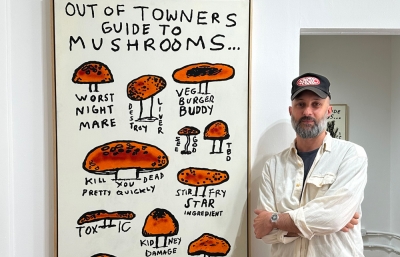

Interview by Doug Gillen and Evan Pricco // Portrait by Doug Gillen

Iconic bands have, one would say, an iconic aesthetic. You can go down the list of popular bands over the last half century or so and sort of connect the dots, visualizing their creative output in pictures. Radiohead has always been an anomaly in that sense; a massive band that was able to navigate the turn of the century at the height of their pop-cultural powers and make, perhaps, one of the greatest creative left turns in music history, which, in turn, led to acclaim and two albums, Kid A and Amnesiac that, to this day, have come to define an apex in popular music.

It has been well-documented for decades, but Radiohead’s frontman Thom Yorke and his art school friend Stanley Donwood have collaborated on the artwork for each of the band’s albums and Yorke’s solo work since The Bends. And yet, as the band approached this particular era as an anniversary, Yorke got what he described as a “bee in his bonnet” to re-approach the massive amount of artwork made during these recording sessions, highlighting them as important documents of their respective careers. The following is an excerpt from a Radio Juxtapoz conversation with the two, just as the Kid A Mnesia box set, 300-page art catalogue, cassettes, and paperback book releases were set to celebrate the anniversary. Reflecting on two decades, both Yorke and Donwood found a manic period of making, an incredibly vast output of artwork that was influenced by David Hockney and a delightful naivety in making art. —Evan Pricco

Doug Gillen: I guess a decent place to start is by revisiting something seminal from the past? The most obvious place to start with this is why.

Thom Yorke: It felt like someone turned a high strength electromagnetic magnet on a while back.

Stanley Donwood: We'd done OK Computer, 20 years on because, basically, we've always made a lot more works than we needed to package a record, and there's been a lot of, not really ephemera, but a kind of world created around what we do for each project, as I call them. We don't use it because, especially with a record company, you can only have 24 pages in a CD booklet and there's a limited number of surfaces on a vinyl package. So, we had so much more.

TY: I had a bee in my bonnet ever since we finished those records (Kid A and Amnesiac). I guess maybe it was a personal thing for me. That was the first time where I'd started to really enjoy being involved in the artwork side and it was like a way out of the weight creatively being put on the music. It was a way to have enough creative outlets with Mr. Donwood in the shed or on the computer.

When we did OK Computer, it was like, "Ah! Do something. Ah! Let's do this. Ah!" It was all done with a scanner, and then suddenly we had this huge, big space and there was this sense of release and excitement.

SD: And time, as well, because the success of OK Computer had made the record company relatively relaxed on how much time we could have and how much freedom we could have essentially with the packaging for the record. I don't think they quite anticipated how far I was going to take that.

TY: There was no deadline, no nothing. We sort of just hit upon a few different things as it was going. We didn't think about it much, which happened to be the way we did the music. There was a lot of scratching around and then it was like preparatory work and things started gelling.

Evan Pricco: But when you guys start with something like this, when you say "Okay, we're going to revisit the artwork for these albums” where is it all? Where do you guys go for these archives? Where did you keep it?

SD: I kept large paintings in a kind of terrible storage unit; it was totally unsecure and uninsured and locked with a combination padlock. It was laughable, but because I'd just moved, I had to arrange everything really quickly and so, it was a lot of happenstance. I had stuff in the attic of a studio.

TY: My office found all my notebooks. I'd lost them, but they'd taken them and protected it all without me knowing. It was a bit like that. Same with the sound files. That was tricky. We found 95% of it in the end but it's been quite a struggle and we found all this video stuff that we'd forgotten existed.

DG: This was such a pivotal moment for you as a collective and a band, and I know particularly for you, Thom, as well. How does it feel revisiting this?

TY: We both had the same problem, but it was just quite alarming discovering our state of mind [from that time], rediscovering our state of mind, barely recognizing the people involved…

But there was this sort of interim period where we're developing the idea of the exhibition and we were rediscovering all the work and it was a bit of a gift, really. I don't think we really noticed what we were doing the first time because it was one of those moments which doesn't always happen. I think, when you look back retrospectively, you understand a little of the context. It was pre-millennium, it was the war in Kosovo, and where we were [at as a band] and you see the work again and it feels sort of… I mean, it feels more significant now than it did then… to me, weirdly.

EP: And are you adding new elements?

SD: No, we didn't. There's no new work. It's like a mantra, no new work. We couldn't adjust anything, we couldn't make anything better.

EP: There wasn’t anything you wanted to adapt or change?

SD: No, actually, because at that time, I think everyone was, for one reason or another, not in a particularly good place mentally, emotionally. I just sort of didn't want to revisit it early on. With all of the stuff that was going on politically, culturally, we were kind of eating this stuff up and then spitting it out as new work back then.

We have all this material that we'd made as a sort of slightly deranged people, so when we look back, from the perspective of 2019-2020, it was, “Okay, I don't want to be that person anymore,” but what we did is quite impressive when we were those people.

TY: The funny thing was there was this sort of confidence in the multidirectional madness. We were absolutely, totally confident that this would all form together into something that made sense. At no point did we ever stand there and go, "What the living fuck is this supposed to be?" We just did stuff and it was the same musically. There was a very long period where we were like, "We're just going to do stuff. We're not going to worry about it…”

After we'd gone through the initial pains of starting, there's all these different narratives, these different characters, these different ideas. This idea of landscape, this idea of a minotaur. It wasn't like we ever sat down and said, "We're going to pursue the concept of landscape." It just happened.

EP: So, you two have known each other since art school. Did it feel a little bit like that kind of bravura where you thought, “I don't know any better so we're just going to make as much stuff as possible?” Art school kids now have an expectation they're going to have exhibitions and they're going to take over the world, but back in the late 1980s, there wasn't that level of confidence.

SD: No, we had an expectation we were going to have to get a shitty job or go on the dole.

TY: Most of our friends, when we left art school, everyone was really, really struggling. The first thing they tell you at art school is, "Yeah, you're not going to get a job out of this." We had this weird thing, we were talking about this yesterday, but I think we hid behind the fact that it was cover art for a record, so it's not really “art.”

SD: It's commercial.

TY: So, we don't have to take ourselves seriously and we spent an awful lot of time and energy making very, very sure that everything we possibly did, we also tore to pieces artistically within whatever we were writing. Everything sort of had this self-annihilating quality to it, just to make sure that there was no mistake that anyone could possibly assume that we believed in anything we possibly did. [Laughs]

DG: Has that dynamic changed since then?

TY: We got these paintings at Christie's, so maybe?

SD: I think, at the time, I was really against the term “graphic design,” because graphic design used to be known as commercial art. I much prefer how that encompasses all art. All art is commercial because all art… apart from possibly religious iconography, which is made for the glory of whichever deity it's aimed at, is commercial. I wanted to sort of extend that out and sort of prove that all the stuff in the fancy galleries and everywhere is all commercial art. It's all the same.

TY: We did fall out of art college and the thing we absolutely agreed about was that. I mean, we didn't know that we'd end up working together when we left art college.

DG: How did working together come back in?

TY: I signed to EMI Records within four months of leaving college and then was spinning out because they had their way of doing the packaging, which was like, "Do you like this? Okay, good." That's it.

EP: No annihilation, no tearing to shreds, none of that process.

TY: I would try to have a conversation with a very well meaning chap about trying to develop ideas and I was, like, "Well, I'm either going to have to do this myself, and I don't have enough confidence to do that, or I'm going to have to call Stanley because I can't handle this sort of..." I'm too much of an artist to just let someone do this, but I'm not enough of an artist to believe I can do it on my own. And I'm busy anyway. [For the second album, The Bends] I basically said to EMI, "Give me four grand. I'm going to do it with a mate." And they're like, "Okay.”

EP: Did you say, “Don't worry, I went to art school…”?

TY: I'm a fucking professional, you know. I'm fully trained! [Laughs]. I went and bought all this computer stuff, spent three weeks trying to make it work, gave up on the printer completely, but managed to figure out Photoshop and then we were off, really.

DG: What was it then that made you want to use the digital component you started with on Kid A? Why weren't you just painting in a more traditional manner?

TY: That's a good question. I mean, I left art school working on computers and he did printmaking. It did not even vaguely occur to us that we'd actually make real marks for a while, and one of the most exciting things was when we bought a scanner and a tablet to do this! It was like two children who'd just been shown how technology works and we both thought, "Wait a minute."

SD: Super early days of the internet as well. The internet at the time was a blank sketchbook, and you could draw whatever you wanted on it. There were a lot of limitations but also a lot of possibilities.

EP: But, in the end, it still had to be an album cover. Once you did The Bends, you could kind of think, "Okay, we're going to do OK Computer now," and the record company is, like, "Okay,” or are they still kind of like, "What are you guys doing?"

SD: They were okay with OK Computer.

TY: There were some excellent meetings that we had…

SD: About font size.

TY: We'd always go in with a design and have no text on it at all. We'd both be sitting there going, "Really? Come on. Everybody knows it's us. We don't need to put us on it."

DG: Is that because it changed the meaning?

TY: No, because we didn't know what the fuck we were doing.

DG: What was this dynamic then while you were creating the artwork for Kid A and Amnesia?

TY: We spent a lot of time in the studio. As a band, we went to Copenhagen and Paris and they were both sort of car crashes. Things did come out of them, but it was really, really... It was entirely my fault because I basically said I didn't think we should rehearse anything. So there we were, everybody going, "So what are we doing?" It'll just come, far too long of me sitting behind a bong going, "Look, it's really obvious! Fuck's sake!”

SD: When we were in Paris, we saw this incredible David Hockney show at the Pompidou which was…

TY: Totally blew our minds.

SD: That show was a big influence on what we proceeded to do. Then, in Copenhagen, there's an amazing museum in the middle of this park that had all these trees with little fingers on them. All the artwork in that museum, it was just… I don't know, we were in this very receptive state of mind.

TY: Wasted, you mean.

SD: Well, yeah I don't know if we were smoking that much then.

EP: What was it about the David Hockney show that seemed to open the way for you?

TY: The funny thing is we'd started pissing around with landscapes a bit. For me, that was my way out, but I don't think we thought about it in terms of…

SD: It was a show where he had all of his paintings of the Grand Canyon. He's kind of an amazing artist. But these ones of the Grand Canyon, they were orange straight out of the tube. It was incredible. They were just like, "Whoa!" and then I think, almost straight after that, he started doing the beginnings of the East Yorkshire paintings that again were just like, "Wow!" Kind of like the joy that a child has making a picture with no expectation and no one's going to tell him it's shit, the way that children draw. It was like that. It had that fantastic energy.

TY: Which, for a couple of art students, who were under pressure to now produce new work, it was like carte blanche, you are free. You can go anywhere you like, it's okay. It was a bit like that.

DG: Does that help or hinder the creative process? Because sometimes if you're sitting there and you've got three colors that aren't the right colors, it just forces you into a creative method that's maybe a little different. Then sometimes, when you don't have any limitations, it's actually at the expense of not having something there to guide you.

TY: Our limitation was ourselves. I mean, our biggest problem was, like I said earlier, this self-annihilating, “Everything is shit. Everything we do is shit.”

EP: You guys are your own judge and jury at this point? It's not like the other bandmates are coming in being, like, "Guys, you need to use some more orange here."

TY: Imagine that. It was really nice. The funny thing was that the painting studio, if you wanted to call it that, that we shared with the rats or whatever, had a lovely little wood burning stove in it and people would come in just to get away from listening to the same 18 bars of music for four days. So they'd come and chill. The paintings were a refuge.

EP: Do you get a chance to actually go and see many art exhibitions and appreciate what others are doing?

TY: We're both very similar in a sense, and I do the same in music as well; and nowadays, I watch my son doing it with music and I watch my daughter doing it with film, that thing where if you watch something, or you look at something, and have an emotional reaction to it—then straight after, it's like, "Okay, how do they do it? How do they get to that point?" And the conversations revolve around literally standing in front of a painting going, "Okay, but how did they do that?”

DG: You've previously compared music to mathematics in that it's a series of elements patterned to make you feel that thing. Do you feel that the visual arts have a similar structure to mathematics?

TY: It's slightly different with music because music evolves over time, everything's a division of time. Whereas with art, you're working with a still moment, in theory. Click. Does that make sense? That sort of makes sense. No matter what you do with music, you're working with patterns. It doesn't matter what you do, doesn't matter how. It's a patent of some description, whether it's even just sound waves that are bouncing against each other, they form a pattern as they do that.

Whereas with art, it's a different part of you. Sometimes to me, an emotional response to a piece of art is like being shown something you've wanted to see for the first time. It's like something you'd hoped you'd see and then eventually, someone's done it. I have the same thing with music though. If I listen to a piece of music, it's like, "Thank God, someone's finally done that because that needed to be done."

EP: When you guys met each other in art school, were you like, "I'm going to be this," and, "I'm going to be this… "?

TY: No. I went to art school because it was a strong look. [Laughs]

EP: It seems like every album is a chance to really make a new project every single time you guys do something. Nothing is stale or recycled.

TY: The hardest bit has been it's been impossible for me, personally, the way I'm built, I can't stand the idea of repeating myself. I'm horrified by the idea. I mean, it happens because it's, "Oh shit, that's my voice on the record. Nevermind." There is an element of repetition.

SD: I thought I was deliberately trying to be a different person for each project, and I do think of them as projects because there's quite a lot around just the record. But when I did my monograph, when I spoke to Juxtapoz last, that was the first time I put it all together. It was like, "Oh, ah, it is definitely the same [artist]." There's something, and it is tough, though I’m not sure what.

TY: But the desire to just reinvent everything, every time. It’s hard to do, but that's what keeps us going.

Full conversation available via Radio Juxtapoz podcast. Radiohead’s Kid A Mnesia 21st anniversary box set, book and other releases came out in fall 2021 via XL Recordings and Radiohead.co.uk.