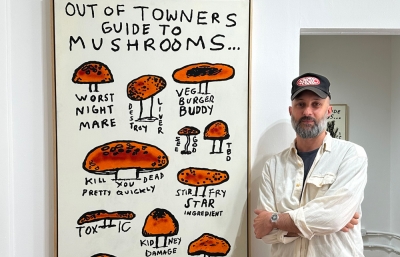

Few artists we've covered in our 25 years have affirmed such an evolutionary flow quite like Los Angeles-based, Tim Biskup. There is integrity in this growth, as he sets new challenges, constantly mining for new influences and methods of creating. Biskup turned 50 in 2017, and even looking back at past features and his 2004 cover story, there remains a youthful energy in everything he does. From personal works, to opening his own gallery, workshop and project space, Face Guts, to his brand new monograph and autobiography, Tree of Life, being released this fall, it feels like Biskup lives a personal renaissance in constant motion. On the eve of his book release, Tim sat down with actress and friend Patricia Arquette to talk about a life and practice resulting in a most legendary career. —Evan Pricco

Patricia Arquette: What did art mean to you when you were a little boy, and what place did it serve?

Tim Biskup: I remember drawing pictures of my monster models. I would try and capture what they were for me, not just in the way that they looked. I didn't think of it this way back then, but I would do an abstraction of Frankenstein: a green block with eyes and bolts on the neck. It felt like this ethereal, magical realm where I wanted to exist, Disneyland and Star Wars, monsters and all that stuff. It was simultaneously terrifying and inspiring. Everything's like that for me.

Your monsters seem gentle.

Maybe that's me wanting to ease into feelings. Helper was goofy and cute when I first started drawing it. Over time, I started to apply new meanings and change the way I drew it. I started to look at freemasonry, American history and the symbolism of the single eye. It took on a whole other meaning. I started to think of this cute guy as a symbol of myopic, white male energy. This cyclops is what man becomes when he believes he knows the will of God. As soon as you put yourself in that position, you lose the ability to see things in perspective and you become a monster. You become Donald Trump.

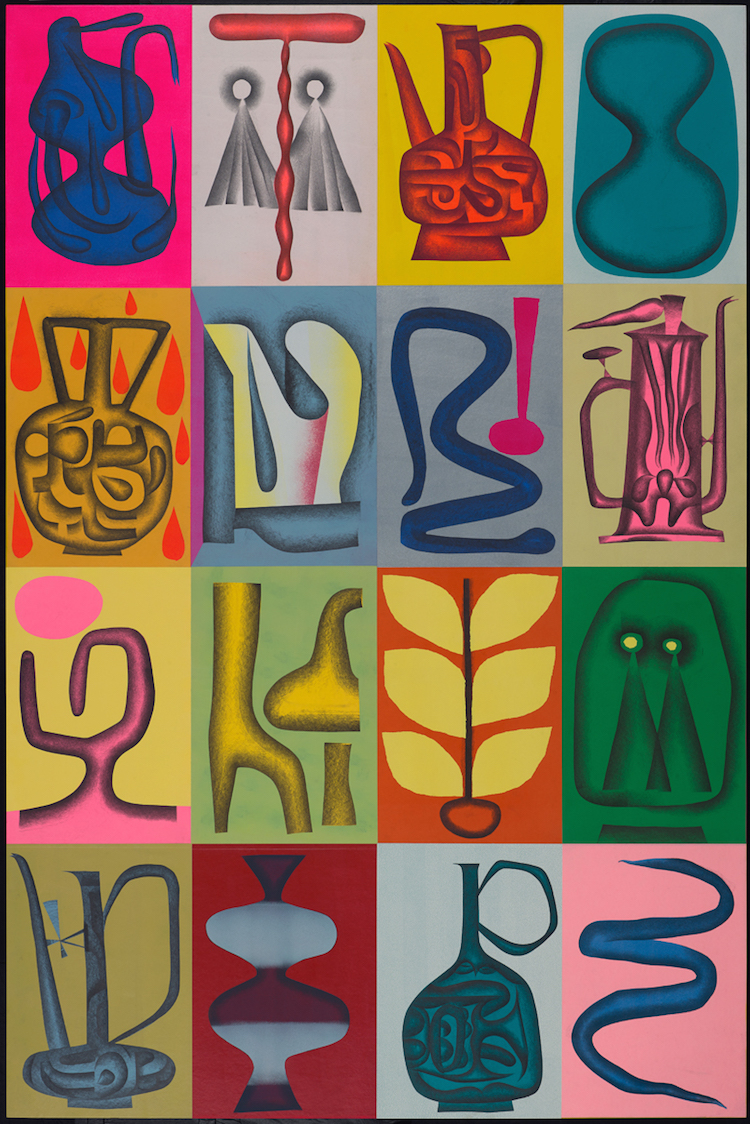

A lot of your other shapes feel tribal in a way. Where did that come from?

There are forms that happen naturally. Carl Jung talks about archetypal symbols that are universal. I don't consciously use them like that, but I know that's what they are. When I'm drawing something that looks like a phallus, there's some essence of maleness to it. When there's something that's vaginal, there's something female to it. I think everything flows back and forth between those two shapes. Something like a vase is both male and female. It's sticking up in the air but contains something. So I think that's why I've been drawing vessels so much. They're a bridge between male and female, beauty and utility. It's a metaphor for everything in life.

You seem to have this really fascinating flow right now where you're examining your art and what it means to you, as well as your spiritual growth and subconscious. There is rigor in the examination of your work. It's not just sitting around drawing or doodling or whatever.

It's life. I remember back in 2008 saying something I'm not sure I completely believed, something like, "My work has become a way of discovering more about myself than about selling work." Now, I think, of course, obviously, that's the way it has to be or else I won't be happy. Self-examination is how you go from the impulse to be an artist to embracing it completely and having it be who you are. I think that you understand these things, as well, because of the way you think about your work. You have to have trust and let it happen in ways that don't feel very comfortable sometimes.

When I was 17, I didn't know if I'd be a good actor, but more than being an actor, what I wanted to be was a brave person. The biggest challenge I had was to act and to be brave all the time 'cause I'd be confronted with failure and rejection constantly. So, I dedicated myself to failing for a year. I'd go on auditions and my agent would get feedback like, "Something is wrong with that girl." I said, "Fuck that. You call them back and tell them that that was a choice. I know you're not used to girls making choices. But that was actually a choice." And so every time I'd get feedback, like, "They didn't think you were right for this part." I would be like, "Fuck, yes. I'm such a badass, brave person that I can keep doing this." I basically tricked myself. I found success that I wouldn't have if I didn't allow myself to fail.

I have an astounding ability to fail. I think my willingness to fail comes from my parents' support. Even though they didn't necessarily feel like what I was doing was the best thing for me, they always said, "You want to try something else? Fine. Do that." I was able to fail without the consequences that everybody else had, so I wasn't afraid of anything. I wasn't afraid to start doing art auctions at bars because, why the fuck not? I've realized that it's not necessarily going to make me the most successful artist in the world but it is going to keep me honest. Doing something like The Dog, a pop-up bar installation I did in Miami during Art Basel 2016, took a big leap of faith because there was no real plan for what I was going to do. I just kept working on it and it came together. Like walking off the cliff and expecting the bridge to be there. I came right home and started working on Face Guts. It made me trust myself more.

When women are giving birth, they say the baby is about to come when the mother says, "I can't do this." But because of this training of fearlessness to some extent, I never thought I couldn't do it. I thought it hurt like hell and I might die, but I never thought I couldn't fucking do it.

Yeah. I have this record in my head of all these moments of fear, like when a car drove through our house when I was small. It seemed like every six months something crazy happened that reminded me of my mortality. I used to think of myself as being a fearful person because I was afraid of everything as a kid. But being able to come back from those moments is the most important lesson of my life. Feeling like you're worthless and then finding value in yourself— it's incredibly difficult, but, like you said, the job is to be brave. That makes so much sense to me. That my job is to overcome those moments of fear, moments when even my life is challenged and I can come out of it by making something beautiful.

So you're not afraid of mistakes and you don't have set in your mind something that you're already planning to make? Are you sort of like, "Let me go and see what I discover?"

Yeah, I'm starting to see how much flexibility I need to have in order to do good work. I have to let myself meander off into an idea that seems relevant because that's the thing that's gonna get me to a more authentic place. When I feel stressed out or angry or something like that, all I have to do is pick up that graphite and start pushing it around, and my mind focuses on that. These drawings happen so fast that I lose myself in them and each stroke turns into memories that appear in the past behind me. It's meditative and therapeutic. I stop thinking constricting thoughts like, what am I going to do with this? Who's going to want it? Why am I doing it? I pared my work down to construction paper and graphite because that pushes everything else out the window. When I go that deep, I feel like I make work that's connected to my soul, the part of myself that I don't think anybody's going to understand until I put it front of them and they look at it and go, “Oh my god.”

It seems like there's kind of a lockdown on the art business. What is acceptable? What is real art? What is of value? So many times artists lose their way because they're giving that power over to other people.

Absolutely. I think that's why I had such a hard time with art school. It was a whole shitload of opinions and prejudices. When they told me, "You're never going to get anywhere doing that!" I was like, "Oh, shit." I wanted to get away from it more than I wanted to operate within it, so I got away. And I really didn't want to be an artist anymore at that point. It crushed my will to hear that over and over again.

You've found a lot of different ways to stand up for your art. How are you so prolific in the face of that rejection?

It's a constant battle. I think it's extremely rare that somebody naturally has the qualities that it takes to make art within the confines of the art world and still be true to themselves. Part of me agrees that I will never be successful because of who I am, that's the prison in the back of my mind. I grew up thinking that I'm faulty because I'm extremely sensitive and emotional, that I can't really be myself because it makes people uncomfortable.

Isn't that the norm for artists?

I think ADD/ADHD is just being an artist.

In school, you almost get in trouble for being the curious person. You're allowed to learn about an explorer who discovered a continent and was very curious and invested years into it, but you'd better not be curious.

You'd better not be looking out the window at a bird while somebody's trying to explain something to you.

Or humming while you're working.

Over and over again I heard, "Tim's so smart, but he doesn't seem to be able to get his work done.” I heard that as, "He's smart but he's completely fucking crazy and he's a big problem for us." Being the big problem has been what I identified with ever since then. So when I was in art school, I was like, "Shit, I'm doing this wrong.”

You were a punk rocker, right? Do you think that gave you better tools for survival?

Yes. Being able to say, "Fuck it, I don't care," is a very healthy thing. I've often said that the most valuable art supply that you have is right here.

That's your middle finger.

Yes. There's so much of punk rock that is based on loose energy. It's not necessarily about doing everything right. It's about capturing the energy of that moment. There's so much punk rock music that is perfect and there's so much of it that just sounds like trash. I think punk rock taught me how easy it is to make shitty music and how easy it is to make great music. The element that makes the difference is a willingness to work hard on the things that you need to work on and to ignore the things that don't matter. That lesson has followed me through everything in my life. There are a lot of times where I'm like, "Oh, shoot. I'm not doing this part right," but it doesn't matter. I cannot do things right if it feels important to not do them right.

You and your brothers are artists, but your parents are not. That's pretty crazy. Why do you think three artists came out of your family? Do you think, in a weird way, it was you kids feeding each other?

Maybe, but both my parents were very creative people who raised us in a culture where being an artist was not considered a good life path. In my mom's photo albums and phone notes, there were always little doodles of birds and flowers floating around the edges.

Now you've got your own space and a book coming out!

The idea behind Face Guts was really for me to put things next to my work that tell people how to see it, like putting the right piece of furniture next to a painting or giving it space. That's kind of the way I approached the book. I want it to teach people how to look at my work in a particular way, not verbally, but by putting the pieces in front of them that, to me, are the finest examples of that moment, and to connect them with the work that came before and after. I worked on the book while Face Guts was being created, so they evolved together, and they both became life-changing projects. I put so much of myself into them. The book became a literal autobiography and made me put my whole life into perspective.

Is there any art you've wanted to make that you thought was too much?

Yes! Oh, my God, yes, so many little visions that I have in my head where I'm like, "What? That's so weird." I can't imagine putting that in front of somebody and saying, "Here you go. This is my art." I'm still learning not to edit everything I do down to what I think people are going to be able to wrap their heads around. More and more, I'm letting myself make work that looks like the shit going on in my head. That's the real art. Those things that confuse even me. That's my soul speaking to me.

So, what about Lowbrow? There were all these different art movements that were doing new things. Have any of them ever been disparaged in the way the Lowbrow art movement was?

I always compare it to punk rock. Punk rock came as a response to the structure of the music world in a lot of ways. It was a lot about politics. It was a lot about class. But if you look from a purely artistic place, it was a reckless, insane thing that people were able to change the way we thought about music. I think there's something in Lowbrow that's very similar. All these people started saying, "I don't have to be in a blue-chip gallery to make art. I don't even have to be in a gallery at all. I can just put it on this skateboard."

"I don't even have to go to art school?"

Yes. None of it. That looseness is kind of like the first phase of punk rock.

Don't you think some day, it will be seen as a value and find its place in history?

I think what happened with punk rock is that it stayed underground until Nirvana came along. Nirvana destroyed the music world because they took this unruly thing and they put a pop sensibility and production and everything that the music audience really wanted into it, and made it palatable for everyone. It had that authentic scream in “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” When that hit the radio, all those fucking bands who were going, "Woohoo!” all of a sudden, sounded fake. The real scream came through. I had this vision of there being a moment in the art world when the “Nirvana” would come along and the artists would be able to wrap their heads around the most authentic parts of themselves, and do it so well that it overwhelms people's prejudices.