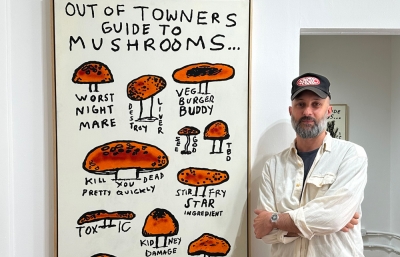

Shyama Golden

Mirrors and Windows

Interview by Kristin Farr // Portrait by Paul Trillo

Shyama Golden is a surrealist storyteller, weaving together a multiplex of references to envision her own lyrical journey of endless rebirth. Los Angeles, Golden’s home, is a primary character in her work, as she merges her internal and external landscapes, mining the mystical to conjure reflections. Allegories abound in her richly detailed paintings. Our story begins with the artist falling down a gopher hole…

Kristin Farr: Tell me about the symbolism and magical realism in your work.

Shyama Golden: I think of my work as building a world that makes visible the reality of how things feel, and that’s where it overlaps with magical realism. I’ve built up a visual language of symbols that can have multiple meanings. Fear of driving serves as a metaphor for the question of free will, fear of taking risks, and a reference to America’s car culture. Cones can be markers of uncertain terrain, as well as unwritten rules. Gopher holes are portals to the unknown and also a visual representation of the ground we walk on growing more and more unstable. I’m drawn to certain images and interpret them as interpreting a dream, drawing connections between the content of the images, the feelings they evoke, and things I’m already thinking about consciously.

Blood Orange Moon, 60"x72", Oil on linen, 2024

Tell me more about your last solo show, In My Mind, Out My Mind.

The show made use of narrative and dream logic, echoing a story of rebirth happening both in my life and the world at large. The paintings depict my discovery of a gopher hole that is a portal to my subconscious world. In that dimension, I get into a car accident with a giant version of myself, injuring and entering my belly through the wound, which, in turn, becomes another portal which leads to my rebirth in the LA River. The theme of rebirth comes up often for me, and in this case, it’s about a rebirth that can happen many times in one lifetime. I go through many transformations, but I must continually be reborn as I keep stumbling and, along with all of humanity, have more to learn. In The Passage, a painting I made during the pandemic, when the blissful ignorance of routine life was disrupted, I foreshadowed this journey by using an egg inside a tree as a symbol for potential for rebirth.

Tell me about The Double and how it relates to Close to Home.

The Double takes place in the subconscious dimension I fell into. It depicts a large-scale masked dancer, which resembles both a Mexican Mojiganga and a Sri Lankan Kolam dancer. There are different meanings for the word Kolam in Tamil, Sinhala, and other South Asian cultures, but I’m referring to a masked dance traditionally used to parody different archetypes of people, which I see as similar to the Mojiganga.

Upon seeing the Mojiganga for the first time in Oaxaca, I felt such joy in looking up at the giant dancers, but was promptly brought back down to earth when my eyes made contact with the stressed-out person inside the belly, struggling to keep it upright and moving. This felt like a manifestation of the human condition in modern times, our own sweaty effort to prop up our identities and make sure the world sees us as we want to be seen, often requiring an effortful performance.

Close to Home is the painting where I crashed into my giant alter ego while driving in the subconscious world. The person inside the figure from The Double is now missing, leaving behind a hollow shell with a glowing red void inside, forming the new portal in the belly of the beast.

The title Close to Home came from the fact that this landscape is one close to my home, where I regularly walk, but also because the idea of death or serious injury in a car accident that is my own fault is a real fear that often feels overwhelming to me—and too embarrassing to talk about.

Close to Home, 60"x72", Oil on linen, 2024

I’m curious about the figures and objects in Daydream of a Nocturne.

In Daydream of a Nocturne, I am making an offering to another alter-ego. In this case, it’s another version of myself wearing a yakka mask. The yakka is an unseen spirit from Sri Lankan folklore that can cause mental and physical ailments in people, but which can also be appeased by an offering given in a special dusk-till-dawn exorcism ritual called Thovil. These rituals involve all-night dancing and drumming that induces a trance-like state in the patient, allowing access to the subconscious so the ritual can work. Dancers costumed as yakkas perform, and towards the end of the ceremony, a healer will eventually get the patient to laugh at a yakka, leading to the catharsis that comes from laughing at one’s own demons.

I wanted to depict a process like this happening in my own mind, where I give form to my own human flaws and give them an offering. The tone is somber but yakkas are attracted to pungent meats like fish and pork, so we share fish with sambol and a classic corn dog. The oil lamps are typical of devotional offerings and the banana leaf is a traditional way of serving special meals.

The yakka I reference for this painting is the demon of the graveyard, and the scene takes place among the graves in Hollywood Cemetery which, in real life, is populated by peacocks who are native to Sri lanka and India. I’m interested in how LA is a pastiche of things from around the world that create a backdrop for a certain version of the American dream which then gets exported to the whole world through Hollywood.

The Hollywood Forever Cemetery is legendary among artists. What about it compels you?

What interested me in that particular cemetery was its dual function as a place to honor the dead, as well as being an entertainment venue. I saw American Psycho for the first of many times when it screened there in the early 2000s, and it still holds up, in case anyone’s wondering. The LA artist Nao Bustamante bought a plot at Hollywood Forever and turned it into a “grave gallery” that you can find on Google maps. I was lucky to see her unforgettable performance there last year and was able to take the reference photos for my painting.

Daydream of a Nocturne, Oil on linen, 72"x60", 2023

What are some other LA locations that inspire you?

My neighborhood of Mount Washington probably inspires me the most, partly because I live here, so it’s most familiar to me. It has a lot of quirks in common with other hillside neighborhoods in LA. The slopes make much of it unbuildable, but that preserves some of the green areas and wildness that would have been flattened for more housing on hospitable terrain. We can see the downtown skyline from our neighborhood, yet it feels quiet and removed. There is a lot of wildlife, with coyotes and skunks roaming the streets, and hawks circling above. There are also plenty of abandoned cars, trash, weeds, squirrels and raccoons, reminders that you’re in the city. This tension between city life and wilderness is another theme that often creeps into my work.

Do you consider the paintings self portraits?

I do, though I’m more concerned with my mental landscape than how I capture a likeness. It is definitely convenient to use myself as a model as it removes the political considerations of depicting the “other,” who would be anybody who isn’t me, even if they are of the same race and gender. This is an age-old problem in art, but I ultimately think even when I am depicting the other, it will probably say more about me and my choices in depicting the subject than it does about them. As I am still introducing myself to the world as an artist, it felt important to start with self portraits, and it also gives me more room to try something weird without having to consider how it might affect someone else.

What are some elements of your work that you return to most often?

Themes I often spend time with these days are the isolation of modern life, the construction of identities for both people and places, self-invention, societal decay, and reincarnation. There have been elements of trash represented in many of my recent paintings, and this reflects the reality of my surroundings living in a city, but also ties in with many of the other themes. I also love to make plants and inanimate objects into characters in my work. Anytime I can challenge a hard category such as living and non-living, conscious and unconscious, that’s something I find interesting because it is part of seeing the world as one organism where everything blurs together.

The Double, 30"x36", Oil on linen, 2024

How is it that you started oil painting at 12?

I started oil painting at 12, but I never said they were good oil paintings. I learned from books and made a lot of rookie mistakes, and sometimes my paintings never dried. I don’t recommend oil painting for children unless there’s proper guidance, as I could have burned the place down and probably did breathe a lot of fumes that weren’t good for my brain. Eventually, once I figured out the right formulas, I realized that oils are actually easier for me than acrylics; they give you more time to work and that was a huge blessing.

I’ve gone back and forth between oils and acrylics over the years and each medium has its curses. Oils can darken over time and become transparent, betraying layers and corrections you thought were hidden. You can see this in museums where a horse’s or nobleman’s leg was repositioned and now reveals a ghosted image. Acrylics darken right away as they dry, making it a pain to match colors. There is a smaller learning curve to acrylic painting, as even some very smart dogs can do it, but a lot more skill and decisiveness is needed to make a great painting that way.

How has living in LA influenced your work, and do you have a favorite place you’ve lived?

Many of my paintings depict locations from my neighborhood, familiar places that LA locals will recognize. It’s hard to name a favorite place, as I appreciated each place during the time I lived there. I’m committed to LA for the foreseeable future as there is no perfect place, as so much is lost with every move, and I feel a need to put down roots. LA has easily become a part of my work as I’m drawn to the histories that the trees and plants here hold. Both the transplanted and native elements reflect patterns in the world, like the creation of neo-European landscapes around the world.

Tell me more about your interest in plants.

I’ve learned a lot more about plants, trees and soil since moving to LA from Brooklyn, which is ironic because my parents grow their own food and my dad was a soil scientist before he retired. I still live in a massive city, but in New York I had no place to grow anything outside, and before that, I was more into buildings than plants. I’ve been digging into how the trees that shape the identity of LA ended up getting here. The plants LA is known for, palms, bougainvillea, hibiscus, bird of paradise, cypress, eucalyptus and jacaranda were brought in from around the world, and the entire place has been terraformed by settlers to create the fantasy of a paradise in the west. It was intended to be a haven for white settlers who were replacing Mexican and Indigenous people at a rapid rate after the building of the railroads, but some of these non-native plants do remind me of Sri Lanka, as well. At first it feels comforting to see them, but they have a dark history.

Though it’s not about LA, Amitav Ghosh’s Curse of the Nutmeg has some solid insights on the relationship between trees and colonialism. In the book, he talks about the Neo-Europes that were built all over the world. Originally, before water was re–routed, LA would have been a mix of wetland, shrub, prairie, and oak woodland environments. Most wetland was drained and filled in, then the LA River was paved with concrete. Personally, I appreciate the beauty of all these plants, including the invasive ones, but I also know there are consequences for engineering the land to accommodate so many people living in a place that is prone to fire and earthquakes, and using plants that didn’t evolve for this landscape. The appearance of things and the reality of things are at odds here.

Beyond just LA, I’m interested in many different plants that form the identity of a place. For example, hot chillies are native to Mexico and Central America and were brought to South Asia by Portuguese colonizers. Hot chiles are so vital to the cuisine of the subcontinent that it’s hard to imagine they aren’t native, let alone that they were brought by colonizers. At this point in time, there’s no such thing as a pure nationalist identity, as cultures have been mixing to the point where the origins of even the most iconic things are complicated.

Incarnation, Oil on canvas, 60"x72", 2022

Have you had any surprising reactions to your work?

The most unexpected reaction for me has been how the work was received in Sri Lanka. Even though I’m referencing Thovil practices from my own culture and have educated myself on the histories and meanings behind them, it’s still appropriation because I’m not embedded in the communities that actually practice them. I’m taking liberties with these elements and recontextualizing them and wasn’t sure if they would connect or if it would simply feel too weird to people there. I was both honored and surprised when I was asked to show my work at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Sri Lanka. It also opened my eyes to many great artists from the diaspora.

My work isn’t aiming for representation for those who perform or experience Thovil exorcism rituals because I wouldn’t be the ideal artist to do this. Instead, I use the imagery as a visual language to explore what’s happening in my own mind. This is how I make my emotional reality visible to others. What I’ve noticed is that younger generations, both in Sri Lanka and elsewhere, understand this approach. We’re in an increasingly hybrid world, and the cultural collisions in my paintings resonate with them.

I see the figure of the yakka from both an insider and outsider perspective. They fascinate me because they embody contradictions—humorous yet frightening, cruel but capable of protection. Unlike the one-dimensional demons of modern western culture, Yakkas retain the complexity that existed in pagan daemons before the church flattened them into simple categories of good and evil.

Why are you drawn to juxtaposing folklore with contemporary life?

Folklore is a way of understanding the world, full of symbolism and archetypes, while contemporary life feels fragmented and uncertain. By bringing these two worlds together, I’m hoping to make sense of my own life in the context of mythologies of the past. Folklore also evolves as people reinterpret it; in that way, it is kept alive, just as a culture that never changes is dead. I want to explore how these ancient stories can still speak to the psychological and emotional realities of living today, especially as someone who is straddling multiple cultures and perspectives. We often only see the stories from western tradition reflected in painting in the US, but the folklore of many cultures can relate to our current predicament.

Someplace Like Home, 72" x 60", Oil on linen, 2024

Tell me about your upcoming show in London.

It will be a series that explores my past lives using Sri Lankan Kolam masks to represent other people I have been in my previous births. The ideas for the stories of my literal past lives all come from my metaphorical past lives: living in Texas, working as a commercial artist, living in Sri Lanka, my obsession with plants, etc. It will also have a short film component in partnership with my husband Paul Trillo, who is a brilliant director and artist. This will be our first real collaboration and my first film.

Where do you hope your work will be found in 100 years?

I was last asked this question over a decade ago, and at that time I thought most of my work would be destined for the landfills in 100 years time. If that sounds negative, consider that most art ends up in the dustheap of history and we only get to know about an infinitesimally small percentage of bygone artists.

Daydream of a Nocturne was recently acquired by LACMA and it makes me feel like some of the work will be preserved, and that is something I always hoped for but never expected. Either way, in 100 years, I’ll be long dead, and hopefully reborn as another artist.

Shyama Golden opens a new solo show on May 20, 2025 at PM/AM Gallery in London and will run through July 1, 2025. This interview was originally published in our WINTER 2025 Quarterly