Rene Magritte

The Fifth Season at SFMOMA

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait Image by The Artist

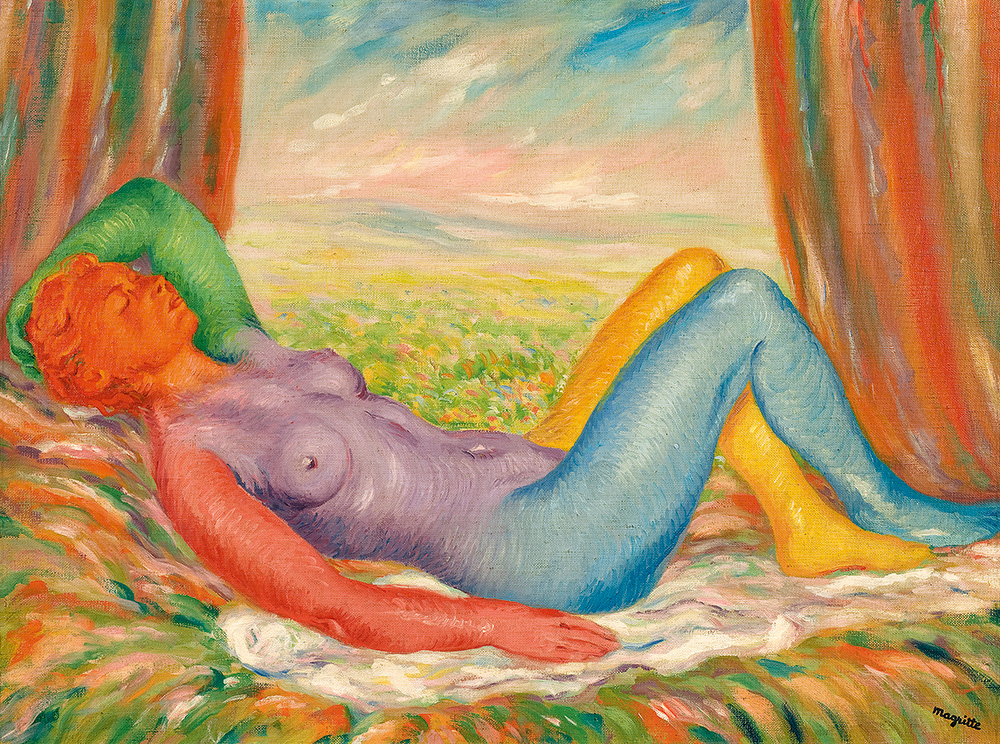

Enigma, so immediately onomatopoetic in association with Rene Magritte, he who made frequent appearances in his own works, mysteriously anonymous in bowler hat and tailored black coat. The precise images for which he’s known are as sharp-edged as the hard “g” in enigma, as in, “something or someone concealing a hidden or known thing under obscure words or forms.” After the war, his paintbrush shocked with color flurries as he sprung Sunlit Surrealism, and the outrage-inducing Vauch period, which open San Francisco MOMA’s big new show. From this startling start, The Fifth Season presents nine installations exploring the provocative painter who pondered, “how we see the world,” whether through a window, immersed in day and night through dark and light, suspended between gliding and gravity, or face-to-face with a giant green apple. I spoke with Caitlin Haskell, Associate Curator of Painting at SFMOMA, where The Fifth Season opens on May 19, 2018.

Gwynned Vitello: André Breton, the Father of Surrealism, dubbed Magritte a Surrealist “in spite of himself.” Your press release states that he rebelled against Surrealist orthodoxy in the ’40s. So, was he or wasn’t he, and either way, how did this shift come about?

Caitlin Haskell: Yes, “Was he or wasn’t he?” If it were possible to be both a Surrealist and not, I think Magritte would have preferred that option. The last big Magritte show in the United States was a wonderful project called The Mystery of the Ordinary, and it looked at the years between 1926 and 1938, which the subtitle called the “essential Surrealist years.” And, yes, during that period, Magritte was active in Brussels, Paris, and London, and he was clearly part of the Surrealist group. But he was also at the fringes, and as Breton indicates, by appearing to be so bourgeois and looking so normative, he went against the Surrealist grain. Some of that was for show and some, I suspect, was genuinely his temperament.

Of course, I have the image of Salvador Dalí with a giant waxed moustache!

In some ways, he’s the anti-Dalí, totally buttoned up and wanting to be ordinary, anonymous, resisting any kind of outsized artistic personality. Magritte was always very well-mannered, very moderate in his behavior. And when it came to his art, he didn’t want it to be about him, either. He was much more interested in shedding light on ideas that are common, or beliefs that are so second-nature we aren’t aware of them.

The painting that opens our show is a terrific example called Hegel’s Vacation, and it has two elements: a water glass set atop an umbrella. Even though Magritte’s name is on the canvas, and even though he’s conceived of this rebus-like image—which, as he might put it, solves the “problem” of water—it’s not really about Magritte, but rather about us, our unspoken associations with water, which the composition teases out. It’s an absurd picture, but psychologically, it resonates. The glass contains water, the umbrella repels it. Spatially, it also gets you thinking. What’s on top and what's on the bottom? What’s inside and out? He’s creating this provocative, mysterious complex of images that you and I can puzzle over in our own heads. Anyway, that is the type of Surrealist that Magritte is, creating revelations by crashing images off of each other. The viewer is always a participant, a co-conspirator in creating the work. Our show, which looks at the years 1943 to the end of his life in 1967, considers a moment after the Surrealist group had largely disbanded. And it starts in a moment when Magritte was very conflicted, and these images from the Sunlit Surrealist and Vache periods do not look like “Magrittes” at all.

Would an expert looking at the Sunlit Surrealist and Vache pieces recognize them as Magrittes? Were there any elements common to his previous or future works?

People who know Magritte are aware of these periods. But here you have an artist who is so interested in visual similitude, and he is deliberately not looking like himself. He’s saying, “Well, now I’m going to do an Impressionist painting for you. I’m going to do a pantomime of Impressionism. And you’re not going to know how I really feel about this.” To me, they’re very clearly the work of an artist who has been thinking a lot about truth and falsehood in art—the treachery of images. And with Sunlit Surrealism, he’s trying to find a new way forward for what Surrealism might become, during and after the war.

I didn’t know he coined the term, but it’s a perfect description of the work.

He wrote a few manifestoes of “Surrealism in the Sunshine.” Some people call it Sunlit Surrealism, other people call it his Renoir period. If you look at a painting in the show, Harvest, you’ll see that it’s a nude straight out of late Renoir, a beautiful female nude against a spring landscape, very pastoral. But Magritte paints one arm in green, another in red and the torso in purple, and he’s messing with the audience—he’s taking all of the eroticism out of the picture, and you start to think, “Why paint this, what is this for?”

Is it true that this period was a reaction to the war? It also sounds like much more.

Magritte is thinking about what an artist can do in very troubling times. Some of the earliest writing on the paintings in this style points out that Magritte is trying to change the use of painting—trying to use painting to raise questions about what is good and bad in life and art. What good can artists do when the world is falling apart?

And that, in fact, is a question that we pose pretty directly in the exhibition’s first gallery. We considered titling it, “What Good is a Painting?” It looks at the Sunlit paintings and Vache pictures together and tests this idea that some “bad pictures” might be able to do some social good. They should get you thinking about the assumptions that we bring to a beautiful picture. Has the world changed so much that painting shouldn’t be about beauty right now? What is the place of beauty in war? Should art have more critical objectives?

Magritte also maintains that if he had worked in his earlier style, exhibiting something like The Treachery of Images (“This is Not a Pipe”) he would have been censored. So, in a way, this is also about getting past censorship. It may look very banal, but it’s serious work, what Magritte called a counter-offensive, a deliberate mix of menace and charm.

He had a respected reputation and had sold a number of paintings. Weren’t these just too shocking?

Yes, they were shocking, despite not being scandalous in a traditional way. And they were not at all successful. They didn’t sell. They were a recipe for financial and career disaster, but Magritte really stood behind the ideas. He felt that Surrealism should not just be a movement bookended by two wars.

Why were the Vache painting so-called? It couldn't be just straight from word meaning.

Vache, in this sense, does not mean cow. Vacherie is French for behaving badly, being nasty. So don’t think of the Laughing Cow rounds of cheese!

Magritte is a very complex character, and I feel like I’m thinking too much when I look at his paintings.

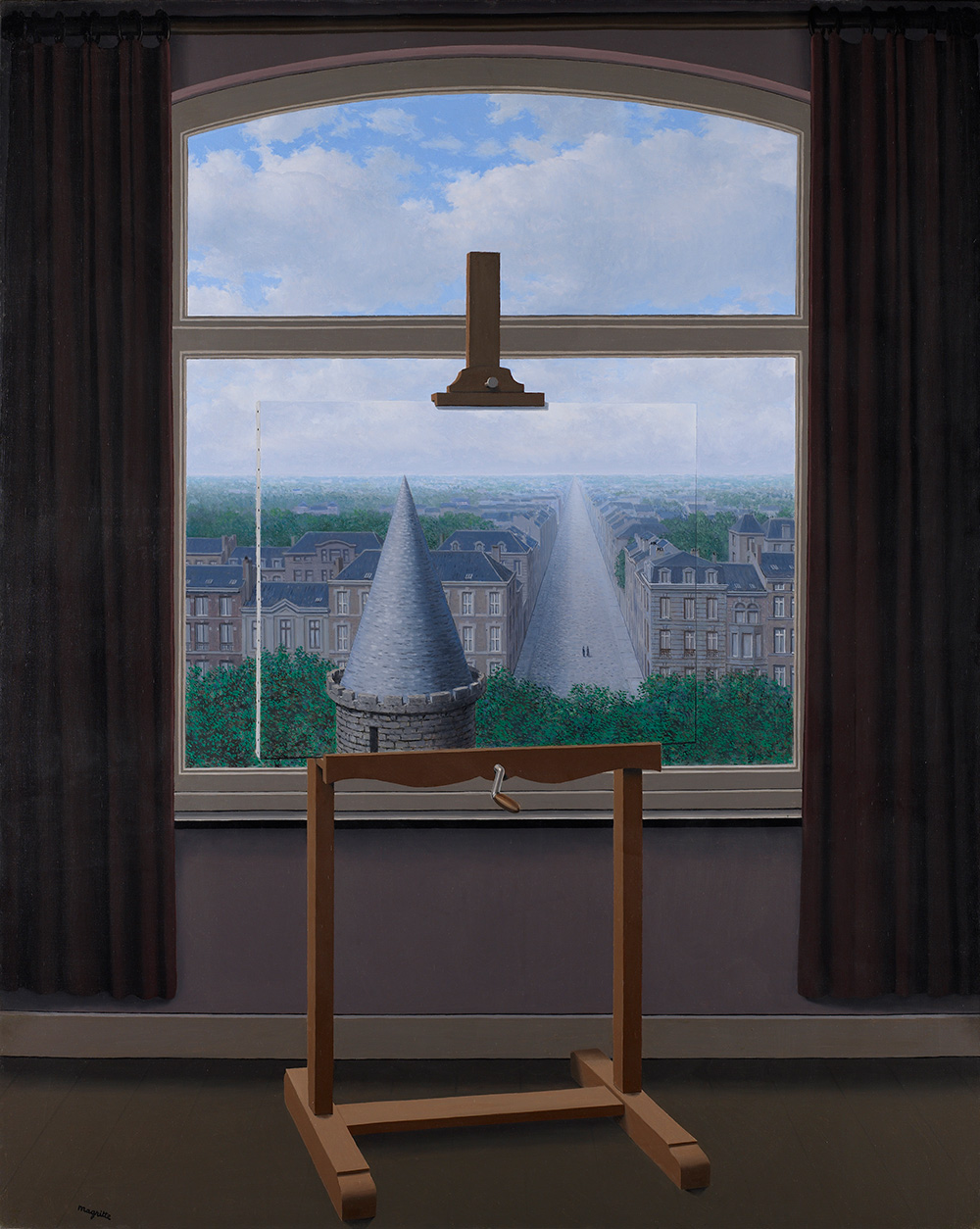

He is a very philosophical painter. In our show, you go from this gallery about faux expressionism into one which is very philosophical and is about what he called “the problem of the window.” He does a series of these sort of self-sufficient images, paintings about paintings. He shows us an easel, for example, unattended but seemingly still in use, with the tacking margin of the canvas going down the edge. And he sets this easel painting in front of a window. And because the scene on the canvas appears to be a perfect representation of what is outside the window, you start to wonder if the landscape you’re looking at is inside or outside the room. Is the tree here, on the easel, or is it over there in the garden? The same brushstrokes represent both things. It’s this very clever play where simply by putting a frame within the picture, Magritte gets you to sort of toggle back and forth. Am I looking at a tree that is natural or artificial? And the really beautiful thing about a painting is that it can be both. It doesn’t have to have just one identity.

He was also a photographer, so he is evidently setting up the picture. I guess that gave him an eye to see through to another dimension.

Yes, it’s almost as though he is setting up a photograph. He’s really a classic picture maker, and he gets a lot of tricks from cinematographers for still and moving images. It just so happens that he carries them out in painting.

He was very prolific, and painted from home, didn’t he?

Yes, he really worked meticulously, and here’s another part of his bourgeois persona: He didn’t paint in a studio, but worked in his house—on carpeted floors—dressed in his suit, keeping very fixed hours. He’d paint in the morning, go into town in the afternoon, play chess or watch a movie, enjoy some conversation.

That’s funny because he was telling us to look at things differently, experience life differently.

He’s sort of doing all of this through the powers of his mind—critical thinking and using his imagination, asking questions. Really, I think he would say, “It’s not that I’m special, it’s that the world is so special.” Once you start looking around the world as this place of true inherent mysteries, you don't need anyone to make it special. You just need to be open to seeing it as such. We’re living in a wondrous mystery, and we’ve sort of trained ourselves, through habit and convention, and through an excessive belief in rationalism, to make the mystery normative.

Who are the writers and painters who influenced him?

He was very aware of the whole history of European painting; plus, he was Belgian, from the place where oil painting originated. He could make beautiful, very technically crafted paintings, like SFMOMA’s Personal Values. On the literary front, he loved Edgar Allan Poe, Stéphane Mallarmé… he also liked a good detective story. Among artists who were his contemporaries, I would say he was not at all tempted to become an Abstract Expressionist. He was vocal about his love of Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings, and had a very famous encounter with a particular painting of his—The Song of Love—that Magritte said set him on the course of becoming a Surrealist painter.

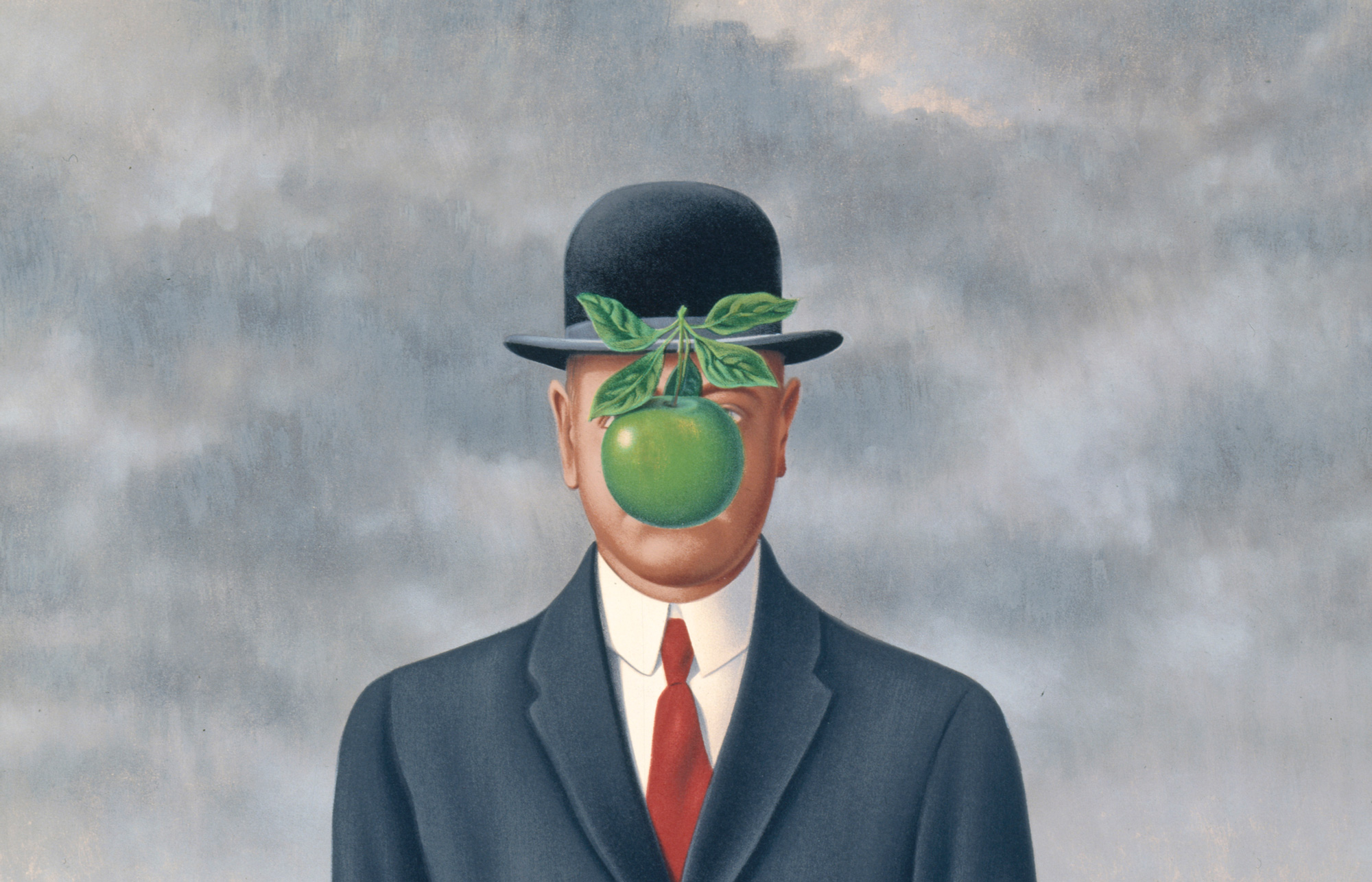

He shared de Chirico’s belief that painting was poetry, right? And Magritte also presented unexpected and seemingly unrelated objects in a painting. This gives me an opportunity to ask if there will be apples in the show, and if it’s a stretch to wonder if they have to do with Eve in the Garden.

Well, he uses very loaded symbols, and you can take it in that direction if you want, but you’re never going to be able to fully resolve the symbolism. However, we do have a lot of great apples in the show, including The Son of Man, of course, which might have prompted you to think of apples in The Garden of Eden.

Since we don't exactly have access to him, we’re using that for his portrait.

That’s a great one, and he identified it as a self-portrait. We also have other apples—two versions of the Listening Room—that will be in the show. There are about 75 works in all.

Tell me a little about how it will be presented.

So, the Magritte experience will start right when you exit the elevator, and you will move through a progression of theatrical curtains. The exhibition itself is thematically organized, and it moves from the 1940s at the start of the show, to the 1960s at the end of the show, but it’s not strictly chronological. We start with the Renoir and Vache pictures, and the Human Condition pictures, as I was saying. Then you move into a gallery of the Hypertrophy pictures—objects that are out of scale with the architecture that contains them.

I didn’t realize until looking it up that the word hypertrophy refers to enlarged growth and is generally connected to physical organs.

It does have a medical definition. In the paintings, there’s a connotation of magnitude but also malignancy, or a type of swelling outside of our control, like you want to stop it, but can’t. There is a sense that these apples are swelling.

Apples again! And we, partly because of their size, find ourselves scrutinizing them.

It’s as if they are under a microscope. We will have the largest presentation of hypertrophy pictures that has ever been brought together. One reason for the show happening now is that 2018 marks 20 years since SFMOMA acquired Personal Values, a major hypertrophy work in Magritte’s late career that holds a prized place in our collection. We wanted to show that painting in a robust context of closely related works.

I’d like to hear about the gallery you're calling “Hidden and Revealed.”

The title is a quote from a radio interview Magritte gave in the mid-1960s where he says, “Everything we see hides another thing,” referring to how you are always seeing only a portion of reality, how you can never get a full picture anywhere. It’s about sight but it’s also about desire and the impossibility of seeing it all. We used this space to look at his gouaches, and it’s a very eclectic grouping. Some are in the Sunlit styles, others in the more classic palette. There are works where you can really see his hand as an artist and his invention.

Of course, there is a gallery of bowler men, and this is where the galleries start to feel more immersive. Then there is a gallery inspired by a 360-degree panorama Magritte worked on in the 1950s, which again, speaks to this idea of what is hidden and revealed. If you make a painting that’s 360 degrees, it’s assumed that it is more comprehensive than any other type of painting. But then again, you cannot see all of it at once because some will always be behind you. It’s a spectacular piece where Magritte took his most famous motifs and put them together in a continuous story that wraps right around you.

He spoke about how one should react to paintings immediately, but that one should be thinking about them. So, am I supposed to think or just react?

I hope there’s a sense that these images hit you right over the head at first, and then there’s something that plays out over a longer period of time. They should stick with you, even when the concept seems very distilled or self-evident.

In the gallery housing the Dominion of Light series, you have daytime skies and nighttime street scenes, and there is a way to understand these paintings as dealing with time. They might be two moments in a single day where morning and evening are disconnected. Or you could think of them as presenting a time lapse, where you see the day start and conclude.

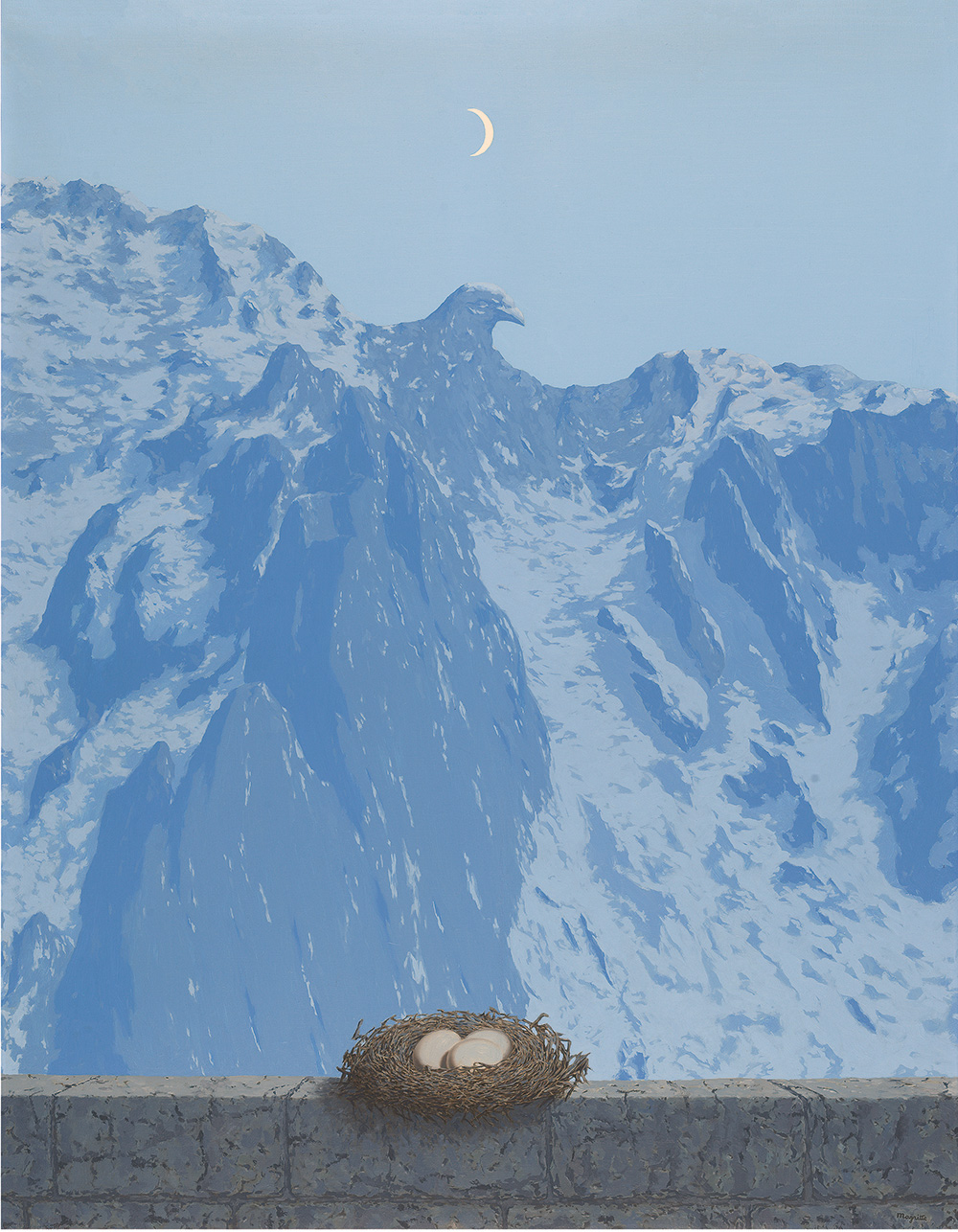

The last theme is about gravity and flight, and we begin with the Domain of Arnheim, a gorgeous piece that Magritte’s wife Georgette lived with during her lifetime. It shows an eagle in the form of a mountain, or vice versa. In either case, you’ve got the animate and the inanimate, the strong and fragile all coming together in the image.

I hope this exhibit introduces more people to the breadth of his work, not to mention the poetry and philosophy of the man in the suit and bowler hat.

That’s my hope, too. For people who don’t yet know Magritte’s work, The Fifth Season will be a great introduction. And for people who do know Magritte and think they’ve seen it all, I can promise there will be new discoveries. We are bringing together a lot of works that have never been seen in the U.S. before, and ensembles of paintings that haven’t been seen together anywhere. It should be exciting.

René Magritte: The Fifth Season is on view May 19 through October 28, 2018 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

sfmoma.org