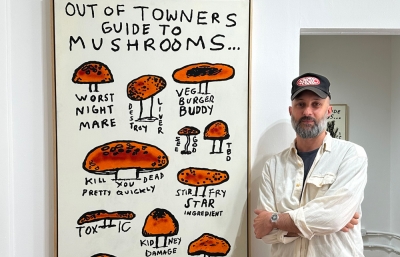

Matt Bollinger

The Realist of Fantasy

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Anne Weber

During such a decade, as we live through the most unreal days, how do you categorize someone as a realist painter? You begin to wonder what it is someone is trying to realistically convey. Before time took new meaning, before daily habits and rituals became nuanced survival mechanisms to combat a new sense of uncertainty, Matt Bollinger was painting and animating a realist fantasy. Our world was, and is, America, but what once appeared to be an era-less, Dust Bowl-to-Recession look at the country now reflects an oeuvre that speaks to the contemporary landscape like few other artists currently exploring the theme.

I came to Bollinger’s work through his animations, subtle, hand-drawn, stop-motion works that were amazingly lonely, funny, articulate, sad and real, all at the same time. Over the past few years, through standout series like Labor Day, Furlough and Collective Conscious, Bollinger has captured an intricate interpretation of a collective malaise, a detailed view of the in-between moments of work and family life reminiscent of Walker Evans or Robert Frank’s mid-twentieth century documentations. America is at a crossroads, and Bollinger is letting the still moments move and the moving images sit still.

I spoke with Bollinger on a cold winter day while he was in the studio in Ithaca, New York, where he, his wife and new daughter have been living for the last few years. He looks forward to solo shows this year with mother’s tankstation in Dublin, Ireland and Zürcher Gallery in NYC. We spoke of flat landscapes, the WPA and how his writing shapes his fine art—but mostly, we just mused about the fantastical realism we are all living through.

Evan Pricco: Let’s start here: what should we call Matt Bollinger?

Matt Bollinger: Yeah, I don't know. I think of myself as a painter, but then I do other things and I make films. I mean, an artist, I guess. Sometimes that feels a little pretentious but what can you do?

I had to ask because you're somebody who takes a moving scene and stops it, but also someone who takes a still moment and moves it, so there's this conversation you're having with both bodies of work at all times.

The way that I think of it, because the two things are formally so different from one another, is that there's a narrative world in the animations, and then these works drop down out of it. It's like a big umbrella because, for a little while, it was confusing, even to me. It was like, "Is the painting coming from the animation or the animation coming from the painting?" And then I realized everything was coming from my drawing and narrative, my writing, the writing part of the studio. I spent a lot of time in my sketchbook doing tiny drawings, and then the images either want to move or they want to be still. And it tends to be whether or not they arrive as a scenario or they arrive as a pictorial framework, like a set of geometry that works within a rectangle or something.

I think in the solo shows you've done, there's a narrative that's moving, even though the images aren't. A story unfolds in the stillness, and when I see your animations, I can see where a solo show will happen from that. And another thing I was thinking about today, would you characterize your works as sad?

I think some of them are sad or maybe melancholy. They're not full blown sad. Melancholy is sad with contemplation thrown in. They're a little reflective. I've done some animations, especially animations that I think are funny, but other people don't necessarily find them to be. I don't know. Maybe I have a sad-looking sense of humor. I made this animation called “Apartment 6F” where the character looks like me, and one of my friends was like, "Oh Matt, are you okay? We need to get you some help. Are you calling out to us?" I thought it was funny, but in some of the paintings, I think that there's something about contemplation and restraint and the stillness of the paintings that tends to look sad.

And in some cases, it's just like, "Oh no, this is just what my face looks like when I'm resting or when I'm not talking or something, and I think that the characters have a little bit of that." I painted someone with a smirk recently. It was a real effort to get it to come off because I think the more active facial expressions that we associate with happiness or other emotions tend to draw attention to the artificiality of how still a canvas is. And when you're just sitting there and you've got no expression, the face is going to rest and gravity just pulls us down a little bit.

I think my ultimate goal with the paintings is that they feel like they're there with you. They're in the present tense, and so, that's why having someone smile at you seems really strange because we don't just sit there smiling for 40 years or however long the painting is going to hang on a wall. What’s aspirational on my part is that the paintings will hang on a wall for decades, so that's what I want.

I think America feels sadness at the moment, and the paintings have this reflection of what the collective mood may be. I think the Labor Day and Furlough series especially capture that state of mind. America does feel like this, really beaten down, no matter where you are.

I feel that personally very much, and I think that's definitely a focus of the work. I mean, just the depressing political climate and the anxiety that comes from that. And also, the separateness that has only been made so much worse by Covid was already happening, kind of fueled by the internet echo chambers that certainly fed Trump's election. That's something I definitely see with the conservative side of my family, the people who still are in the Midwest, and it tends to fall along gender lines. The men in my family, as well as my partner's, tend to skew pretty far Republican and then everybody's mom is on the other side, though our siblings are split too. It's impossible to come together right now, where every emotion just gets exacerbated. That's fed all of my work for the last few years.

It's interesting because you could also place the work in the pantheon of great social realist painters as a movement of this working class representation. When I look at your work, I really start to see a sense of the WPA movement, or even Dust Bowl-era photography.

I love that moment in art history. Also, just that period globally, not just the social realist stuff, which I like, but the American Ashcan School movement, modernism and also the new realism in Germany and abstraction. The way that all gets tangled up is really interesting to me. But in retrospect, looking at a lot of that social realist and Ashcan stuff and things like that, it's so sincere. There is a singular purpose. The belief behind the work, the earnestness, is something that I feel might not be possible for me right now because of the complication surrounding the confusion of labor and conservatism. There's been some interesting writing about why working class people vote against seemingly their own interests in so many ways, so I feel that ambiguity and complexity. I don't feel like I can make a celebratory painting. That would be wrong.

Your comments about sincerity make me want to talk about the animations. Was narrative animation something you always wanted to do, or did you find something in your paintings and drawings that led to that being a possibility?

I made videos, not just animation, but other video works when I was in college. Back in undergrad, someone showed me some William Kentridge. I was, like, "Oh, this is really cool. I can understand how you would do this." I had a VHS camcorder that had a single frame button, which dates me a little bit. I did some charcoal animations with it, and I thought, "Oh, this is cool." And then you just have the tape. I didn't edit it. What I shot would just be... and I would show this cassette tape, or this VHS tape to my class, but nobody in the painting department when I was in undergrad was doing anything similar. The feedback would be like, "Oh, this is cool," and that would be it. I should have, in retrospect, brought it to somebody who actually knew about video.

I think it's better you kept learning it yourself, creating a more authentic, real vision. What you said earlier about Ashcan movement work, there’s that sort of earnestness.

All of my weird side routes have led me here. There are no shortcuts. In grad school, I did videos, but not animations. I made puppets and also made costumes and built sets. I used to work from photographs, so I would stage everything. There'd be a script for a series of paintings, basically. That was always there. Then, after school, I went through a long process of, not de-skilling, but re-skilling. I stopped oil painting. I stopped doing everything that I did when I was in school and started just drawing a lot and working more from my imagination and memories. Around 2010, I recorded an interview with my dad about a dramatic event in his life where someone tried to murder him. He was stabbed in the heart and nearly died.

Wow, okay, damn. And where was this?

Kansas City, Missouri. It was a big deal when I was growing up because he had massive scars all over his body and he'd had two open heart surgeries. Anyway, he was just always being operated on. He was 20 when it happened, so it was like, "Whoa, this is something I want to document." He was driving this brand new 1970 Z28 Camaro at the time of the stabbing, so that car keeps appearing in my work. Anyway, I recorded this interview and it became a superstructure, this narrative that my work was filling out. I made a 17-foot drawing of the setting and there was a sculpture with sound that played with the drawing. So, it was a talking drawing or something, actually anticipating how the animation would work, in a way.

This is a very long answer, but the work comes about through observation, documentary research and memory. Fiction and drawing, for me, are really linked up, and it becomes a way of adhering together different experiences to make a structure that could then exist in the work.

You mentioned, as a kid, being sent off to your room, where you would draw and create these fantasy worlds with drawing. Do you think you're painting fantasy worlds now?

I think it occupies the same part of my imagination. It's a brain space that composites together lots of different experiences and things are alive in there. It doesn't feel like a memory. That's where the fictionalization process is. It's a catalyst that activates all those different ingredients that get put in there. Yeah, it feels the same. I was always being kind of accused of excessive daydreaming. I think it really annoyed my dad because I would just make some mistake in the real world because it was like I could barely see out of my eyes because I was looking... they were turned around backwards.

I think it's in the Furlough series, which I love, there is a painting of men around the pickup truck. And to me, it's the most real scene, but it's also this beautiful, fuzzy memory of a place. It's such beautiful realism and a fantasy, as well. I love the way you balance that.

I think it's because the paintings get made by me doing a lot of sketching. Then I start them abstractly with just paint, so the process is a little bit like setting an intention before you do some meditation. I know I want to paint that image of a tiny, three inch drawing that I have right before me, but then I have to look into the painting to have that image be kind of revealed to me. So, in that act of painting, I'm always looking deeper and deeper into the painting and I look less and less outside of it.

At the beginning of the process, I'm doing this abstract stuff, but then I start to build the image. I had drawings of the truck and drawings of some of the individual men's faces, as well as drawings of a boot, just so I know what the stuff was; but then I look less and less at that and more and more into the work, which is where it probably starts to take on that slightly fantasy look. It's a parallel world that closely resembles ours.

Are they based on real people?

No. Sometimes they arrive in the same way that fiction might be thought of, as autobiographical fiction bears a resemblance. I'm thinking about so-and-so's dad when I paint this person, but just as often, I start painting, and they start to resemble someone, and they tell me, "Oh, this is like that guy you knew growing up." But I didn't know that until I started working it up in the paint. That's this idea that the painting is a catalyst. It always activates elements of the imagination and memory. I always want to say the term “trigger,” but that word means something different now. I think of it as that feeling of sudden, unexpected, involuntary recall, but without necessarily the traumatic association.

We’re talking about America, and you grew up right in the middle. Are your paintings about Missouri?

Oftentimes, I think of them as being set in Missouri, but then I've come to realize that outside of big cities, a lot of America looks very similar. The topography will be different, like in the northern part of Missouri, which is a particularly depressing landscape. When you're in the Midwestern portion, it really is just flat. I think you have to be from there or an adjacent state to admire it’s bleak beauty. You can see forever.

I think it's the compositing process because I'm always reacting to what's around me and then trying to relate to it in some way. So that's where sometimes Missouri gets glued right onto Upstate New York or whatever. It was more jarring when I lived in Brooklyn because I would see things around me and would think, "Oh, I want to paint that." But then I would feel like I was trying to be cool or something, or like I'm putting tattoos on people, which ends up being, "Oh, but it looks like I'm trying to be cool." It doesn't feel like me. My people are uncool.

I have been thinking about the specificity, though, because I think specificity is really important at the same time. I think you can have a little bit of, you know, both. I can composite it so there’s this specificity, which I think is necessary to arrive at the general. I think things that begin with the general and then attempt to activate the specific don't tend to work as well for me. So I find that when I see work that has elements of very concrete specificity, it opens up my own experience, and suddenly I'm thinking about my version of whatever that was. It may not be—but it does become real in my mind.

You can watch Matt Bollinger’s animations at mattbollinger.com. His solo shows at mother’s tankstation and Zürcher Gallery will open in fall, 2022.