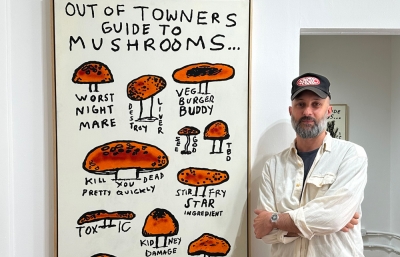

Maria Qamar

The Essence of Hatecopy

Interview by Sarah Hagi // Portrait by Eddie O'Keife

While most of the world has been scrambling to figure out how to take their work digital, Maria Qamar (AKA Hatecopy) has been riding that wave since she first began making art for public consumption in 2015.

After splitting from a copywriting job, Maria created the Instagram account Hatecopy where she began embedding her identity as a Canadian woman of South-Asian descent on recognizable Pop art. Familiar and relatable to brown kids across the diaspora who find themselves straddling two distinct cultures, Hatecopy quickly turned from hobby and stress relieving side-hustle into a passion project, a very popular one.

Five years later, the Toronto based artist has amassed a 200k Instagram following, written a book (a survival guide on dealing with overbearing family members), and been featured in publications like Vogue India, Elle Canada, Toronto Life Magazine, and the New York Times.

As a fellow Torontonian, I long admired Maria as an artist, a bit of a local legend—and over the last few years, as a friend. While visiting her home in September, we sat and talked about what it has been like to carve out a personal digital space in her profession, what it’s like to deal with identity politics in art, and the journey of choosing art as a livelihood.

Sarah Hagi: What has the last year been like for you?

Maria Qamar: So, what month is it already? September? It feels like last month was, like, March, it feels like covid just began. It feels like nothing, like time is just meshing together.

So, what were you doing before? What were your plans before the pandemic hit?

This year was just going to be just focusing on doing more physical shows and painting more and just taking some time to relax from social media. It's funny that, at the end, everything ended up being digital anyway. I ended up having a digital exhibit as opposed to a physical one. And that's probably going to be the norm for a little while, compared to last year, when I had three physical shows.

Where were they?

One of them was in San Francisco, one of them was in New York, and the third was Paris in December. I came back to Toronto, and then a few months later, everything went into lockdown. It’s a weird change from the high energy and big crowds, shaking hands and talking to people and getting to know everybody, to everyone freaking out because of this pandemic that's taking over. And the art world is panicking because nobody has a social media presence. Now everyone's trying to hoard followings.

One thing I found remarkable about your rise to success is how you etched out your own space online. Would you say that has worked to your benefit in a big way now?

I think so, because I didn't have to panic. Because the people that I wanted to talk to, like my friends and family and the people that follow my work, are a very close knit community. Even though it's hundreds of thousands of strangers from across the world, it feels like we're one community and talking to each other about things that concern us. So, in that way, I was kind of already living in my little bubble. It's about time that people stop discounting social media. When we were growing up, people would be making up personalities or like pretending to be somebody else online, but now that’s just who you are in real life.

I think galleries, in particular, and art curators and collectors are looking on Instagram and social media now for artists to have a presence, because, obviously, there's no other way. But I think it's going into a good direction for people that don't have the privilege to go to art school and make those connections and shake hands with people that run galleries.

Describe the trajectory of your career—you, very much your own person in your own space, making art that is so original, but also very familiar to so many people.

It's one of those things where you go, “Oh, right. It makes sense.” It wasn't made to be something that you would look at it in a gallery and tilt your head and go, “I wonder what this means?” It's pretty obvious stuff. What surprises me is people assume that because it's online, it's made to please a mass audience. These are snippets of things that I've experienced. Whenever I make something I don't ever assume that people are gonna like it. I actually assume the opposite. And then when people start commenting like, “Oh my God, this was my childhood,” or whatever, it surprises me. It's like, Oh my God, I can't believe we were all living the same kind of life.

It seems that you have stayed true to yourself and your background, that you see the world without falling into the traps of being marginalized. Was that something you actively fought against?

In the beginning, there were many things that a lot of people would say when talking about my work. They'd be like, “Oh, this South Asian artist…” And it's like, well, I live in Canada, I work from Toronto, I am South Asian, yes. But would you say that about like a white artist? I'm a South Asian artist. I'm an artist who’s making work about my life as a South Asian woman growing up in the West, which is how I describe it.

You’re so well known worldwide now. Do you feel any pressure to fit certain expectations of your own community?

I don't leave my house and I talk to five people, that's how it's always been. I don't have a focus group of people that I run my work by before I put it out there. It's literally just me sitting at home and making stuff and then going, “Okay, well maybe I'll post this today or maybe I'll paint this today.” If a gallery wants to acquire a body of work to do a show, I'll just go, “Okay, well, I have this and this and this.” It might fit the theme of the show, or I’ll come up with a new theme entirely. It's just me sitting at home tinkering away at things until I get what I want.

What I want from a gallery and from the art world is to see some of that seriousness gone. I’d like to be able to walk into a gallery or museum, look at the art, and not feel that tension where it’s like, “Do I have to whisper?” I don't want somebody to walk into one of my exhibits and feel like they can't do something or talk about whatever. I want it to be an experience where you can just come in, laugh if you want, hang out on the ground, or do whatever you want.

I mean, art can be really alienating to some people. How does it feel making yourself accessible through social media? Was it hard to figure out where to draw the line between Maria and Hatecopy?

I thought I wasn’t that private until recently, when I posted a thing about PTSD and getting cheated on, and other personal stuff. I had thousands of women sharing their stories and going, “Oh my God, this is so open and real.” I thought I was always being real and open, but I guess not in this way. Now I realize that I guess I’m not the type who talks about my personal life online. I always thought I did that through my work.

I suppose people don’t realize that your work really draws from your real life.

The aesthetic throws people off because it’s cartoonish and lighthearted. One of the things I think is very interesting is when people come into the gallery, and they go, “Oh, you painted this?” So, I think that's kind of a similar way in which people approach the personality angle of things, like, “I thought this was a curated experience or persona.” But Hatecopy is really who I am!

You managed to do something really difficult for Canadians and that was in becoming an international sensation and finding so much success abroad. What was that experience like for you?

I wasn't even thinking about getting recognized by anybody. Because it was such a slow process. I've been doing this for six or so years. I was always talking to other Desis, and the way I’d put out artwork would be to send it to my brother and somebody who understands me, and if it would make them laugh, then I’d know it was good and I’d put it up.

Would you say you were trying to relate to the people who knew you best?

Yeah, I would send something to my brother and he would say, “Yeah that’s something that happened to you, I remember that.” So, it’s like, cool, this made sense and he understood it immediately. WIth something as literal as my artwork, I have to be able to communicate it clearly, and when you’re scrolling on Instagram, you have somebody’s attention for like three seconds before they scroll away and find something else. So it has to be an easy read, a quick pop of colour, easily digestible, and they can scroll away. That was my process, and a very universal insight about people having short attention spans. I’m also not just talking to the Desi diaspora in Toronto, I’m talking to people everywhere.

What has the journey been like for you, from posting art on Instagram for fun, to evolving into someone who has these huge interactive physical pieces?

When I was working in advertising, we used to get briefs with these massive budgets for these big brands. Our job was to create these experiences that were huge parties with DJs and I want to be able to do that, for just myself, and do that in my work.

My career as an artist means making these experiences and having a good time, and as well as a place where we can go and look at art, and talk about some serious topics, both politically and socially, but still be able to feel comfortable and have a good time and laugh about things.

You made it your own way without any connections, so do you think emerging artists are also forgoing traditional routes?

I didn't come from money. My parents left everything behind when we came here. So, for me, I've always had a kind of mentality of, “Okay, how do I get this for myself? How do I make this happen?” Connections are one of those things that I didn't understand. I'm pretty antisocial— I can't schmooze. They can't put me in a room and have me shake hands with everyone. If people ask where they can see more of my work I just tell them to look on my Instagram.

I don't want to follow a predetermined path for what an artist should be or what a woman should be, or what a South Asian woman should be, or whatever. I think those kinds of rules are literally made to be challenged. So, why not just challenge them?

@hatecopy // This interview was originally published in the Winter 2021 Quarterly.