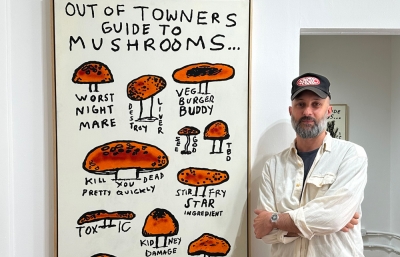

Are you still making a whole painting in one day?

I haven’t for a long time! In my undergrad, I cultivated a very fast method of painting, which is something I still do but apply differently. I thought finishing a painting in a day was the only way to harness that specific energy. As time has gone on, I’ve realized that, actually, to do a painting in a day, I wasn’t making my best work, and I wasn’t making anything properly considered.

How it’s developed over time is that I have that same feeling of urgency, but instead I’ll attack a painting for a couple of hours, and then I’ll come back the next day and I’ll attack it again. It’s better in terms of letting the paint on the palette evolve, to get a skin and all of that, but also to really build it up on the canvas. Practically, I can maintain that high level of energy when I’m working on something in short bursts as opposed to one long shift. I’ll generally work on a few paintings at a time so I can move across them and apply that energy to each one.

Tell me about growing up in Milton Keynes. Were you always drawing?

Contrary to popular UK opinion, l liked growing up in Milton Keynes. I was always drawing, it was just something I did. I used to draw celebrities, and then I would spend lunchtimes copying characters from manga books in the school canteen. As I got older, I would copy paintings by painters I liked, and then I would paint those painters. I remember the first painting I did that was my own, not something for school, was a portrait of Francis Bacon with acrylics. It was just his face really close up, and he had a very pink, hammy quality—I think my dad’s still got it.

Milton Keynes influenced me in lots of ways because it is a very peculiar place. It’s a new town that was built in 1967, and everything is very spaced out, so you’re restricted to where you can get to by bus. One of the main things my friends and I would do on the weekend was go to the cinema and see whatever was on. I saw a real plethora of movies—to this day, I will watch anything, and I do think my interest in film was informed by that.

When you moved to London for art school, how did your perspective shift?

I felt a bit like an alien when I started art school. The first term of my first year, I did photography, and it does make some sense looking back at those works now. I would create these scenes with myself as the lone figure, which referenced the language of film. There wasn’t much painting going on at Goldsmiths at the time, at least that I could see, and it was obvious my heart wasn’t in it with what I was making. I had a really great tutor who eventually took me aside and told me if I wanted to paint, I should just do it. I did, and soon after I stumbled across some small works by Chantal Joffe in a group show. They were small paintings from photographs which were loose and messy, but contemporary, like no paintings I’d seen before.

What are the lighter and heavier topics in your work?

The lighter topics would be looking at characters who are quite pathetic. Figures who don’t help themselves and have childish outbursts. For example, if you look at some of Adam Sandler’s characters, there’s a deep well of sadness that he sort of flops about in. The heavier end would be a darker mental state. An existential kind of a listlessness, a not feeling good enough, which is just the other side of the same coin.

My show Last Dance at Grove in 2023 drew heavily from the film Aftersun by Charlotte Wells. Through that film, I was thinking a lot about specific moments from my own personal history. Painting has always been an outlet for me to interrogate parts of myself I find difficult to reconcile with. It’s challenging because you can pull context from something that is so personal, but it's not something that can necessarily be read. I think because it's such an internal process, you just wonder if any trace of it is left in the work for the viewer.