JR

The Renowned French Street Artist Speaks

Interview and Photos by Annabel Graham // Artwork Photos by Perrotin Gallery

I’m sitting in the pristine, sweeping office of gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin, staring into the eyes of the elusive-yet-ubiquitous French artist known simply as JR. This would be an ordinary turn of events, except for the well-known fact that this particular artist never removes his sunglasses (it’s even a secondary plotline in Faces Places, the Oscar-nominated documentary he made in 2017 with New Wave legend Agnès Varda). Through our conversation, I find out that JR does occasionally take off his sunglasses. Just not in front of cameras. He is not hiding—rather, the degree of mystery he’s cultivated around his identity serves as a sort of reverse disguise, allowing him to pass under the radar sunglass- and hat-less while he visits countries around the world and creates large-scale, ephemeral (and, for the most part, illegal) art installations in public places.

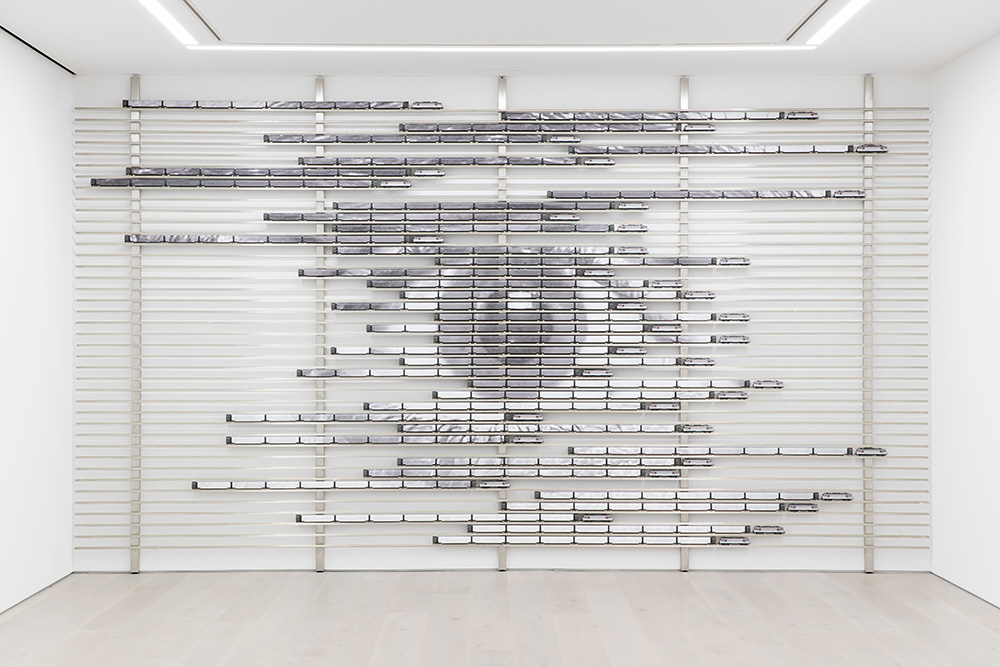

In person, JR is animated, ebullient, and quite funny—unsurprisingly, as there’s a hint of impish playfulness in even his most politically-charged works. Beneath this charm and wit, though, there’s a hyper-focused intensity—a palpable sense of intention, of determination. All of the works showcased in his first New York solo exhibition possess the environmental adaptability and perspective-shifting potential that have become JR’s trademarks—from a short film (narrated by Robert DeNiro) about the immigrant experience at Ellis Island to a mock-up of the container ship emblazoned with a woman’s eyes that sailed in 2014 from Le Havre to Malaysia (the last chapter in the Women Are Heroes project) to the gigantic eye pasted onto the roof of the gallery (on top of which guests stood during a surprise performance by Alicia Keys at the opening afterparty).

During the press preview, JR’s enthusiasm is infectious—he gestures expressively as he details the process of each piece, pulls out his iPhone to show us a video of himself sharing tea with a Border Patrol agent at the giant picnic he organized this past October at the US-Mexico border (on the final day of his Kikito installation, which depicts a larger-than-life Mexican toddler peering curiously over the wall onto Californian soil). The installation—and the picnic—made international news headlines.

To say that the 35-year-old JR wears many hats is an understatement (also a literal fact—sunglass situation aside, he is seldom seen without his signature fedora). He is a photographer, a filmmaker, a guerrilla street artist, and above all an activist fighting for social change through creative, peaceful yet powerful methods. If there’s one thing we learn from his work, it’s the power of context—that the same image pasted in a different setting can have an entirely different meaning, becoming a weapon in one place and a piece of art in another. His immersive, interactive global installations reach far beyond the typical gallery-goer, compelling people around the world not only to engage and connect but also to see things from a new angle.

Much of his work deals with the borders constructed by society—both physical and metaphysical—and the action of making visible, crossing, and breaking down those borders. It’s a timely, powerful and multilayered topic—one he’s been exploring since his first installation seventeen years ago in the squalid housing projects outside of Paris—and it radiates clearly and poignantly through the prints, films and installation pieces that make up his first New York solo exhibition, Horizontal (at Galerie Perrotin through August 17th).

Annabel Graham: Can you speak a bit about what the notion of a "border" means to you and the ways in which you address that notion in the pieces in this show?

JR: We experience borders in completely different ways depending on where we were born. To me personally, being born in France has helped me—it’s allowed me to be on the Palestinian side and the Israeli side, for example, in the same day. For a lot of people that would be impossible. In my work, I’ve always used the fact that I would only get evicted or arrested, whereas someone from another country might go to jail for years for trying the exact same thing. I use that to go and work in different countries and install artworks in places where the local people can’t. In this show, I go from the most physical, constructed, manmade border on this planet [in Kikito] to the natural border of the ocean [in Women Are Heroes] to the invisible border [in Face 2 Face].

You're best known for your guerilla-style street art, and for displaying your work in public places. While putting together this show in a traditional gallery setting, what were some of the biggest differences you encountered, both negative and positive? How is the experience different for the viewer?

For me, gallery shows always depict the different layers of what goes into the work that is displayed outside, which helps viewers understand how the work is made—but I don’t try to recreate the work from outside inside of the gallery. So what I’ve always shown in galleries has been the different blueprints, the plans and preparatory sketches that I prepare beforehand in the studio, and also the shots I’ve taken of the pieces from specific angles. The exhibition is also to present films, and a lot of the installations with electronics and mechanics are pieces that I’ve created specifically for a space like this. A lot of my work is very visible—people can go and see it at the border and other places, but it’s ephemeral—it’s not even signed, I don’t even write my name on it, there’s no trace of it at all after it’s gone. The only trace that we make of it will be the pieces [in the gallery] that will go to the few collectors that we get. 99% of my work is installed in the streets around the world—it’s free for the people, they can take photographs and print them at home if they want, but there’s only 1% of what I do that finances that entire 99%. Which is the complete opposite of a regular artist’s model—but that’s the model that I found from the beginning, and that I love.

What's your take on the possession or preservation of art versus the act of letting go of it, releasing it into the universe where it will inevitably decay? Do you ever feel attachment or nostalgia for an art piece you've created that has long since disappeared?

Not really, because I’ve presented my work in the street from the very beginning. It was just part of the deal that it could be gone in the next hour, in the same night, in the same week—or sometimes it would stay for years. I’ve never had a sense of possession of my work, I’ve always been fine letting it disappear. For me, the only work that remains will be those photographs, those blueprints—and weirdly, when I go back to places where I pasted, even if the work is not there anymore, I talk to people and they can talk about [the work], looking at it as if it’s still there. Even if the physical scaffolding with the image on it is no longer there, they can still see it. I think that’s the power of the mind. We should not underestimate that power.

So much of your work is about giving a voice to the marginalized—helping people to see things from a new perspective, as well as creating a connection between people. Can you talk about voice, perspective, engagement and human connection in your work?

The image is the excuse for people to actually connect in the physical world. That’s a really important thing to me. It’s a mixture between something that’s very physical—that you can only see by being at that location—but also, to get people there, I have to use social media—so the image travels further, and reaches out to people who might not otherwise come to see it. I think that equation brings what I’m really looking for—which is for people to go and see it by themselves, and make their own judgment of the situation. When you go and see Kikito at the border, suddenly you end up in front of that wall, which you might have never seen. You end up talking with people on the other side, you end up understanding their situation a bit better.

My first installation at 18 years old was in one of the worst projects in Paris where no one would go. When I pasted, I invited people to come and see it. And of course people came, but only a few, because on the invitation it says you have to take the train, then the bus, then walk. So it shows how disconnected that neighborhood was from Paris. Since then I’m still on the exact same road, except that now I use the tools that are at my disposal. When I started, I was at the real beginning of digital photography, which allowed someone like me who couldn’t afford it before to be able to start taking photos. But also in this last decade, photography has become a daily thing that can be used by anybody, which is actually really interesting, and I am willing to use that in my work. What I try to capture in every installation is a combination of hand-pasting photography, getting people to physically move to see the work, and also encouraging people to share it to try to touch other people.

Though you don’t make art specifically about yourself, it seems to me that there’s a part of you in each of your works, much in the same way that a novelist is present in his or her own works of fiction. Can you speak to the question of identity when it comes to artmaking, and your own decision not to fully reveal yours? How important is the presence of the artist in a work of art? Will you ever show your face to the world?

When I was working in the favelas, I didn’t wear a hat or glasses. There was no press in there, and I was with the people every day. I know it’s hard to understand for a lot of people, because if you only see my work in New York, you’re like, why is he hiding? What’s the point? But my work is not about just one city, or a few cities where I’m actually welcome in galleries and museums—it’s about creating work in different contexts, and unfortunately, this same work is taken as a crime in one place and as a piece of art in another. I came from graffiti, so that’s why I stayed semi-anonymous in the beginning, but I’ve never refused to speak about my work, because I had to do it when I went to places like Liberia—I had to speak to the people in the street who were the actual curators, who decided if I could do my piece. My aim was always to let the work speak for itself. I don’t work with any brands, anything that can help you trace the angle of the work. When I travel I take off my hat and glasses, and I just work on another identity, which helps me to appear in some countries and disappear when I want to. And as this show proves, Kikito was only possible because of that. So, unfortunately, I have to keep that semi-anonymity—but I never hide my eyes from people, except for in front of a camera or in photographs. Till now, it has been a good protection, but who knows for how long.

What is your process like, from initial idea to the creation of a piece? Do you usually develop the idea for a project before you find the "canvas," or vice versa?

Depends. With Kikito, for example, there was a wall, which you cannot paste on. And so I thought of a structure, and then I looked for the land, and then I realized I would have to dig into the land to make it flat. I always let the architecture dictate the work. That’s why [my pieces] fit in the environment like they’ve always been there, like they belong there. The locals wanted to keep Kikito up, but the problem was that we were renting the scaffolding, and because it’s completely self-financed, we couldn’t afford to rent it for more than a month. But I like the idea that the image was there, and now it’s not, but it’s still traveling through people in a way. More people are seeing it today, whether it’s there or not because they are sharing the image.

What’s your favorite part of what you do?

The people that I meet everywhere I go—and the life of travel that I love. I didn’t travel much when I was young, so for me just going from the suburbs to Paris was a journey. I feel like I’m still on that same subway train that was taking me to Paris, and I always want to go further—to the next country, the next country, the next country. And that’s still what I’m doing today.

And your least favorite?

My least favorite part is the fact that before every project, I always have doubt about it. There’s a fear of failure because it’s risky, and we always kind of risk everything. I hate that moment—I try to remind myself that the biggest mountains are within us. That’s why I often just buy the plane ticket because that way I have to go. When I get there, things work out—at least most of the time. In my studio, I have a big engraving that says “It’s going to be all right.” So we have that in front of us every day because most of the time we’re doing stuff that, on paper, isn’t possible. Sometimes it really isn’t possible. But other times you get surprised, and you come back with images like the picnic [at the border], and then you reconsider certain things.

Do you have a dream project that you’d like to create one day?

I don’t over-plan my dreams. It’s not really the way I think, that I have a goal or a dream—it’s more that I’m on a journey. If you look at all of my projects from the beginning, they’re all interconnected. They each respond to each other. They’re the continuation of my research and my journey and my changing techniques—I use the same kind of imagery, but with different context and different forms, in different places. All of this is the continuation of things I started, which is my way of reassuring myself that I’m following one track.

What change would you most like your work to effect?

Just to be able to change people’s perception of a place is a huge success for me. When I see the impact that a movie like Faces Places had, and I hear people say how it affected them, how they changed their perception about this, about that—I guess that’s the power of art. It helps to change the way you see the world—and then, maybe, the actions you take.

When you were a kid, did you want to be an artist?

No, I didn’t even know there was a job for being an artist. I didn’t know about galleries. I wasn’t raised into it, I didn’t have any connection to [the art world]. When I started with graffiti, it was more a way of saying, “I exist.” You live in the suburbs, in the projects, and you want to have your name out there. I was just writing my name, that’s it. But then when I started meeting other graffiti writers and realizing there was a whole community, I kind of discovered a world. They would not call themselves artists—there was no street art, really, at that time, but it was at the moment when [street art] was about to start. People were calling us vandalistes, and then they said street artists, and then artists—and I think “artist” is what I’ve always been, in a way, without knowing. Now that I understand the meaning of it, I feel proud to be able to use that name.

JR: Horizontal is on view at Galerie Perrotin in NYC through August 17th, 2018.