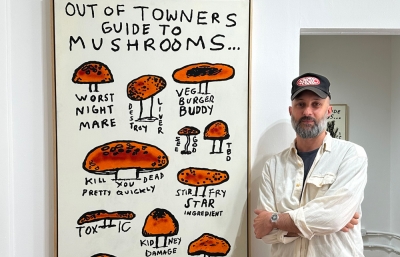

Alvin Armstrong

Rhythm Paintings

Interview by Charles Moore

Alvin Armstrong was all set to become an acupuncturist—then he started painting for 15 hours a day. A powerful work ethic and a love of movement stitch up the sinewy threads that suffuse the artist’s life. Armstong, whose father was in the Navy, spent most of his childhood in San Diego punctuated by vivid recollections of his dad’s deployments in Japan and Hawaii, only to uncover his creative side in college. Enchanted by the live music he heard at Chico State University, the young artist felt compelled to experiment and create. Following an Honorable Discharge from the Coast Guard, a quick visit to New York in early 2013 turned into a permanent transcontinental move: the foundation for a career in painting.

In 2018, half-way through graduate school, Armstrong found firm artistic footing. He had grown disenchanted with the burden of clinical overhead, of establishing clientele as an emerging acupuncturist, and began to reevaluate his lifestyle, including a decision to give up drinking. A trip to the Brooklyn Museum moved Armstrong so greatly that he promptly picked up a set of watercolors and got to work. He still delves into archival imagery on a regular basis, conducting visual research when needed. His series Malcolm Had Feelings Too (2020) featuring 32 portraits of Malcom X mid-speech, embeds a gym-rat, studio-rat approach to routine as he relentlessly pursues technique, theme, and self-improvement.

Today those sunrise-to-sunset workdays happen in Armstrong’s Bushwick studio, where the artist brings to life large-scale scenes full of energy, cropping images so that his subjects extend beyond the border of the canvas, showcasing Black lives in motion. With swathes of vibrant paint and simple, seamless color blocks, he gravitates towards “rhythm paintings,” or those that exude energy right from the canvas. Always, Armstrong is moving—pursuing solo exhibitions, snagging visiting lecturer stints at Rutgers University—and so are his subjects. The visual glimpse into these subjects’ lives palpate with heat and energy.

Charles Moore: Alvin, let's start out by talking about where you're from, and how it was growing up in San Diego. I think you spent part of your life in Hawaii, as well.

Alvin Armstrong: Yes, that’s true. My dad was in the Navy for 22 years. He's originally from the Crenshaw area of LA and my mom is from San Diego, California. Yes, I was born in San Diego and grew up there for the most part. I lived in Japan as a really young kid, and I'm part Japanese, as well. We have family there, too. From Japan, we moved back to California for a little bit, and then Hawaii. Then we returned to California when I was around fourth grade, and we stayed in the San Diego area.

I have fond memories of Japan and Hawaii, but San Diego's really where I grew up. It was wonderful living by the ocean like a water baby. But though I liked a lot of things about that community, I knew that this wasn't really my destination. From an early age, there was just a feeling that I needed to explore more of the world.

What was “more of the world” for you and how did you discover it?

I think, more than anything else, to be honest, it was just getting up from under my dad. My dad was an amazing human in many ways. But with that, he was like an overall umbrella. So I think a lot of it was just getting up from under his grip and discovering my own independence, if you will. So when I graduated high school, I went to college at Chico State, north of Sacramento, California, a place surrounded by farmland.

In that experience, being on my own for the first time, I just began to explore new things as any 18-year-old undergrad would do. The first thing was hearing all this live music. I remember, for the first time, experiencing a live alternative style band, playing their music and just being really impacted. I joined a small college band and learned to play guitar. I started playing my own music and meeting up with other musicians.

I say this just because very quickly, I started to recognize my creative side. Up until then, it was all sports. I didn't have any connection to anything outside of the roots reggae music my dad enjoyed, which was a big part of my life. But I never had a desire to explore my own creativity up until this point.

What prompted your move to New York City?

I moved to New York City in early 2013. I had just been discharged from the Coast Guard, which I had joined out of San Francisco. I really didn't have much desire to live in New York. I had simply gone to visit a friend, and on my third day there, I was offered a job by a friend. I said, yes and I stayed. And so began my New York experience, which was intense.

Speaking of intense, what was it like from that point until you became an artist?

Staying on my friend's couch, I basically was in limbo trying to figure out what I wanted to go into. There was a short transition before I made the decision to go into acupuncture and eastern medicine. It's an intensive four-year graduate program, and it was tough to manage while adjusting to the pace of New York.

I think that's a very interesting transition because it's not like there're a thousand artists who come from the medical field and then become artists—but there are a couple. I can instantly think of Nate Lewis and Henry Taylor.

Nate's a friend of mine—I respect him and his practice very much. Henry's a hero of mine. I was influenced by both those brothers—very much so. When I was halfway through school, I started to understand what it was going to take to be established as an acupuncturist in New York City. I pretty much knew that I probably wasn't going to end up being a clinician. I thought that I could do something else, maybe help on the educational side, or in business communications within practitioners.

At the time, I wasn't involved in fine arts at all, so had no idea that this window was opening. I finished school, but before I began to make professional choices around medicine, I had to take a hard look at my personal life. I decided that I needed to clean up my act and put some old behaviors down. So I stopped drinking completely and began a new course.

And really by that, a lot of things began to change in my life. I found I had so much more time and resources on my hands. I began to try out new things. It was in those early days of exploring my reality that I started going to museums, although I didn't have the capacity to truly appreciate and understand art.

I went to the Brooklyn Museum and was just moved by what was in front of me. Mind you, I still didn't know anything about painting or visual arts, but told myself that I would give it a try. And that's exactly what I went about doing. I began painting and just putting my all into it, painting 15 to 16 hours a day for those first two years nonstop.

And I believed in myself—that my skills could develop. It took a while. It really wasn't until September 2020 that I had my first official show in Brooklyn. Going through that experience and seeing the response of people was when I really got drawn into the art world. That’s when I really started to feel that something real was happening to me.

We’ll discuss your work in a moment, but for now, I want to talk about your reference to painting for 15 hours a day for two years. I know you have a pretty rigid regimen even now. So, tell me about where you inherit that super-structured mindset. And then, could you describe to me those first two years and why you did it that way?

The hustle—the fight in me, if you will—comes from my whole family. We are a sports- and athletics-driven family, from my father to my siblings, cousins, and distant cousins who have made it to the Olympics. My sister is an assistant athletic director at University of Tulsa. My brother played basketball at Columbia in NYC. My nephew plays football at Princeton. His father played in the NBA. My dad went to Portland State University on a basketball scholarship, so that fighting spirit is in the genes.

I’ve always been competitive. I wasn't the fastest or the strongest, but I could always compete with the best because my nature has always been intense. Even if I was clueless, I knew that I would work like a dog until there was improvement. It was like wearing blinders, focusing on what was ahead and moving forward. When I did something and was dissatisfied with it, I didn’t stay there—I just worked at it again until I was satisfied.

And now, tell me about those first two years of working nonstop 15 hours a day. What was that like?

Well, there were roommates, and I was just in my room diving into anything I could find that moved me. I discovered Alice Neal—really drawn to just the life that was emanating from those portraits. And through Alice, I found Henry Taylor. I identified with Henry in so many ways, so it was easy to grab on to that inspiration in the way he worked. I saw how he painted with so much fervor painting nonstop, all the time, leading up to a show, still painting in the show venue, just insanely driven. That moved me. Yes, his work was outstanding, but it was also his pace.

I told myself that I too could expend the same number of hours practicing in order to get better. Those first two years were lonely. I chose to not get a full-time job and work as little as possible while still being able to handle my business. I would cook a big bowl of food with just the basics—rice, vegetables and a protein and I would eat that twice a day. It was a real regimen. And I would literally paint all day.

What were you painting?

I started with watercolors because that's the cheapest route I could go. My first paintings for the first couple of months were all small because I was working out of just one room. But gradually I began to paint larger pieces in watercolor. And when I moved out and got my first apartment, it was then I started painting in earnest.

Having my own space, I was going to immediately try and paint bigger. I wanted to move to acrylics. And so, it was in Crown Heights in my first studio apartment that the work really began to build up. The routine was a lot of the same: wake up with the sun, get to work, paint nonstop, pause for an hour, maybe, cook, eat, get back to it. Paint until basically I was falling asleep, and do it all over again the next day, literally. That’s how the two years went.

At this time my world was small. I had a few friends, but kept pretty much to myself. I wasn't really interested in getting my work out there at that point. I knew I had a long way to go until I was satisfied with the quality of my work. Every now and then someone would suggest, “Hey, are you selling or are you interested in this or that?” My answer was always, “No, I'm just working. I just want to keep my head down and get better.”

I note that August will be four years into painting for you. So how does it look today?

Today, it's a lot of the same. I have my own studio in Bushwick, walking distance from my house. There’s a little bit more room to work in. Now I'm in a relationship, so I try and take weekends for personal time. But Monday through Friday, I’m up with the sun and work till sundown. It’s five days a week at the minimum, though sometimes I can sneak another day in there. But, at the very least, it’s ten hours a day engaged in actual painting.

Painting is on my mind all the time. A lot of what I do outside those hours is dive into archival images. I look at a ton of imagery to find inspiration. But once I enter the studio, I'm usually so amped up I can get into painting quickly. I try and take care of all the prelims before I get into this space. This is tricky because a lot of my practice is front heavy, doing a ton of visual research. But by the time I start painting, it's straightforward. I pretty much know the direction I'm going. Of course, there's a lot that happens along the way, but I know I’m getting there. I handle all that in addition to having to manage the business—which has its own challenges.

I pride myself in being a kind of gym rat/studio rat. I just want my contemporaries in the art world to know, without a doubt, that Alvin is at work in the studio. That's just how I move.

Interestingly, you use the term that I normally hear with abstract painters: “mark-making.” Let's go into what you feel is your mark-making and the description of your signature brush strokes.

Well, from the outset, I always made sure that I practiced my live paintings with the subject in front of me, and really worked on getting that down comfortably in terms of time and technique. I call those my freestyle paintings, and really, the time dictates the style. It's not rushed, but I've done it so much that I'm at home enough to where I can move through quickly.

I try to give life to each painting, evoking emotion with the brush movements. And to give a visual example of my current work, I have a series I worked on all last year that people will see later this year. Each one is about four by six feet, and would take me about two days from beginning to end. That's fairly quick, but still in a discovery phase that I'm still learning.

When the paint starts to settle, I still ask myself what I am going after—I'm always open to further discovery. By the end of that series, that same size painting from beginning to end was taking me roughly three hours, compared to two days. It's not that I'm rushing. With the practice of repetition and rhythm of my movements, when it begins to flow, it can really flow, and, hopefully, people will see this dynamic at play.

My mark-making is what I think people are beginning to recognize in my paintings. In this series, people will be able to see how the mark-making changes over time. I like texture, right? So sometimes that's by adding multiple layers, one on top of the other. As they dry, I just continue to layer to give some more texture. I can also add form by applying less paint and letting the white of the canvas show through.

It's important to me not to be pigeonholed and known for doing one thing. I really am trying to allow myself as many tools and techniques as I can, so I have more options going into the next series. That way, my themes will always change because I want to keep things fresh and stay motivated, and I don't want to limit myself to the same technique. The way that I layer the paint or hold the brush will also vary.

Let’s start with the Malcom X series.

The production started that year on Juneteenth—June 19 is a special day to commemorate the emancipation of enslaved people in the US. In reminiscing on its significance for us in this country, I was inspired to paint Malcolm X, who has always been a hero of mine. I painted him on Juneteenth 2020, and when I stepped away from that painting, it felt right. I ended up painting him two more times that night.

The next morning I just continued and did more. When I got to nine portraits of Malcolm, I wondered how many of these I was going to do. In my daily dive into imagery, I had come across Andy Warhol’s 32 Campbell soup cans, which didn’t inspire me too much. But it did trigger something. “You know what? I told myself, “I'm going to paint Malcolm 32 times in response to those Campbell soups.” That's what I did—I just started painting him, without putting too much thought into it. And when I got to 20 Malcolms, I realized that if I pushed and painted three to four a day on average, I could finish the 32 by July 4th.

Did that date matter in your consciousness?

Yes. I look for other markers of meaning and significance in all of my work, and it just meant so much to me to push for that date. All 32 were painted in three weeks. I was painting three a day, sometimes four, during the last week. On that last day, I only had to paint two to finish. It was really a spiritual experience.

As for the imagery for inspiration, there are about six or seven black and white speeches of Malcolm that are available to the public. I looked at those speeches mid-speech, frame by frame, and from those hundreds of frames, I picked the ones that resonated with me the most. They were all black and white, and all the color for the pieces in color was added by me. Every piece was in color.

I really let go of my limits and just rode on my emotions. I'm extremely proud of that piece. Yes, it's my artistic response to Andy Warhol's 32 Campbell soups, but at heart, it’s a dedication to the black lives lost in America due to police brutality. Malcolm Has Feelings Too is in my studio right now and I hope to show it one day on an institutional circuit for kids to see and remember history and to take pride in.

The portrait of your cousin was in that show as well, so let’s talk about that piece, if you’d like to share.

Yeah, definitely. The portrait was the other large piece in the back of the show. In this, I took a cue from Henry Taylor’s desire for vibrance. This man literally had a show completed when it was just about to open and he was in this space, painting to give the audience the freshness of his mind. From an early point, I told myself that that's something that I wanted to do. And so for my cousin's piece, I painted right up to two days before. In the actual show’s space It was just something I wanted. It’s a large piece, 9-by 12-feet.

To be honest, I didn't know what I was going to paint. I just started putting paint down and I ended up gravitating towards my cousin on my father's side, who had recently died. He had a life that started in gang culture, and he got out of that and changed his life. He had really come a long way. What I depicted was a testament to black America, an embodiment of all the stories of black people in the portrait, of someone who had a rough pass, who I was proud of. Here was a loving man who really made something out of his life.

So I wanted to honor him. I have that one, as well as Malcolm’s in my private collection archive. They were just too personal for me to even offer at that point in time. I titled it Black Is, and I spray painted those words beside the figure—just kinda left it open ended as a surprise element to the show. People walk through the show and go in the back room and leave the show with their thoughts on what Black is.

Let’s come now to the equine pieces. What drew you to this subject?

With the horses, there are a few things. My maternal grandpa had a ranch with horses in Kingman, Arizona. Every time we visited him, we would ride horses. I was always taken up by how beautiful and intelligent they are—such grace and magic! My brother and his wife live in Naples, Florida, where she currently trains thoroughbreds who have retired from racing—saved them from slaughter. She trains and domesticates them so they have a second chance and can be adopted into private homes and become part of families. My niece rides horses for competitions too. The idea of painting horses started with one piece in the last show The Give and Take, where there are two boys riding on the horses in diptych.

Your work really meshes with the theme of this issue. Is there anything you wanted to talk about in terms of movement related to what you're doing currently or plan to do.

I'm very connected to movement as I practice. While not all my paintings depict figures moving, it always plays into what I attempt. I find that I enjoy painting most when I'm trying to depict movement and energy—I call them rhythm paintings. I really gravitate towards this type of kinetic energy appearing to come off the canvas. Because the paintings are two dimensional and flat, I try to create the illusion of greater movement from my brush strokes. It’s extremely challenging to paint in such a way that the movement is grounded and proportional.

You were saying you’re excited about things coming up at the end of the year.

Yes, I am. My year is pretty back heavy. I am looking forward to a solo presentation this year at the Armory show.

Awesome! Before we close, is there anything we didn't talk about that you’d want me to include?

I just want to add that, for me, it’s important to help others, especially younger Black and Brown artists,in the way I've been helped; sharing information and experience in order to hopefully help them along on their path and understanding. In that way, I can give back to society what others have generously given me.