Alicia McCarthy

The Wonderful Weave That Binds Us

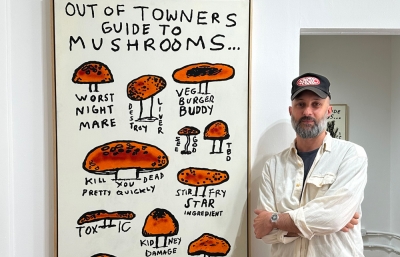

Interview by Sasha Bogojev and portrait by Delon Isaacs

This year, as we celebrate our 25th anniversary, Juxtapoz is honored to sit down and talk with a Bay Area artist who represented the scene surrounding the magazine when it was founded. Back in the 1990s, San Francisco was the mecca for skateboarding kids around the world, but also a vibrant underground art hub, spreading a colorful, contagious vibe around the world through zines, music and occasional features in print. The immediacy of the burgeoning scene connected with other rebellious youth cultures, creating a unique language of punks, surfers, and graffiti outlaws hanging out in the Mission that marked and influenced generations way beyond the Bay Area. Certainly among those artists is Alicia McCarthy, whose work fuses the honest energy of the scene. Folk, graffiti, punk, and abstraction all weave into a labyrinth of loose lines, unexpected visuals and spontaneous personal marks, and the legacy of the Mission School remains a model for many emerging creatives.

Meeting Alicia at the opening of her solo show with Copenhagen's V1 Gallery back in 2018 and having the opportunity to huddle together at the opening of her debut solo show with Brussels' Alice Gallery earlier in 2019 was like being granted access to a documentarian of that time and place. While I had a massive appreciation for her work for the reasons cited, as well as our mutual interests, this conversation revealed a whole new dimension of meanings behind her captivating colorful weaves.

Sasha Bogojev: With Juxtapoz having its 25th anniversary this year, my idea for this interview was to connect that with the early days of The Mission School...

Alicia McCarthy: What's that?

How do you feel about that term?

How I feel about the term is that it stems more back to when Glen Helfand originally wrote the article. So really, it's him and his take on what he observed in the '90s. For me, it was my life. It felt special, but it didn't feel like we were doing something.

Yeah, it doesn't really need a label, does it?

No, not at all, and the hilarious thing is that the people who are listed don't have an attachment to that and aren't the type of people that ever do anything like that.

But, you know, there's usually an urge, especially in the art world, to categorize things.

Right, that your guys' job.

Do you have any idea if there was a defining moment that made that whole scene so widely recognized and popular?

No, and I don't really think about it much, to be honest. But in terms of what resulted in that, I think the critical moment for me was meeting the first group of friends at Humboldt State, which is a college in Northern California. My boyfriend at the time and I transferred down to the SF Art Institute. His father is a Bay Area artist, Richard Shaw. He and Ruby Neri's father are artists in the Bay Area and taught at the Art Institute, and that's how I met Ruby. So, those two things changed my life forever.

Do you feel like the artwork started happening because of the friendships or were the friendships based on the artwork that you were making?

I mean, we were just young and excited to paint, Ruby and I. She certainly wasn't my only friend. I went to school with Xylor Jane, who's a really amazing painter, and you were in an environment where that's what everybody's doing. But Ruby and I painted on each other's things. We went out. We were kind of brats sometimes. We were troublemakers a little bit. Not really troublemakers, but pushing the rules or, just out of excitement, breaking rules without knowing it. So, sometimes innocently, and sometimes not.

And this was happening around the clock. I mean, back in those days, it was drug and alcohol free. It sure didn't help that the job I had was working in a produce department, so I had to be there at 6 a.m. It was rare that I slept six hours a night, and it burst out of sheer excitement and just being immersed in a lot of different communities—it was music, it was political, it was school or painting, it was painting on the street. It was all of it, having a job and being with other creative people.

It feels like you carry a lot of those elements to this day. There's such a strong sense of camaraderie around your show. Do you feel this is imperative in what you do, or should do, or is there just no other option?

Yeah, it's always been that way. So, for me, I think it's my version of the solo show. It's like a self-portrait of me, because I would rather go along with other people. And also, it's a little bit of addressing value. I happen to have a lot of opportunities and I know an enormous amount of equally, if not more, talented and hardworking people, but I also understand how value works.

I mean, even when I first went to college and took a Super 8 film class, we had to do a self-portrait. It happened to be winter and I went with my friends up to the snow and we had these big innertubes, and the self-portrait was handing the camera to each of my friends. I have my insecurities, but it's not that I don't have a sense of myself. It's just my sense of myself has to do with all the people I surround myself with. All of those things are, to me, the content of my paintings as well. So, it's just what I prefer and how I see myself in a lot of ways.

Now that you mentioned your self-portraits, I wonder if you were doing something different than these, let's say, abstract compositions?

Yeah, I worked figuratively for a while until the early or mid-'90s. I went abstract because I felt like I never worked narratively, even though there would be recognizable images and people or figures. I wanted to see if I could get the same emotional quality without it, and again, it would feel a little bit more universal.

Do you feel like you succeeded at achieving that similar atmosphere?

I don't know. Do you? I just don't know [laughs]. I mean, I know how I feel painting. I'm most interested in making the work. Once the painting's done, I'm done. I actually don't even want to look at it to be honest.

I've talked with other artists who shared that same sentiment about their work, too.

I'm very critical of it. I mean, even that last mural that I did was probably one of the things that I've done that has lasted the longest in terms of my enjoyment and the feeling of it. And I'm already at a place that...

You want to paint it over?

No, I don't want to paint it over, but I feel like, "It needs a couple more stripes on the side," you know? But luckily there's no option. Literally, if I finish a painting, it kind of needs to leave.

I was going to ask, are you one of those artists who, if given access to the work, are constantly going to touch it up?

Yeah. I mean, there's a couple of pieces in this show at Alice Gallery. One piece has two or three paintings underneath and showed up with a blank slate. It was one of the early ones that I did when I was working on all of them, and so it sat around longer in my eyesight, and I just... I'm not a huge fan of my work, but I love and need the process. It's a necessary part of my life.

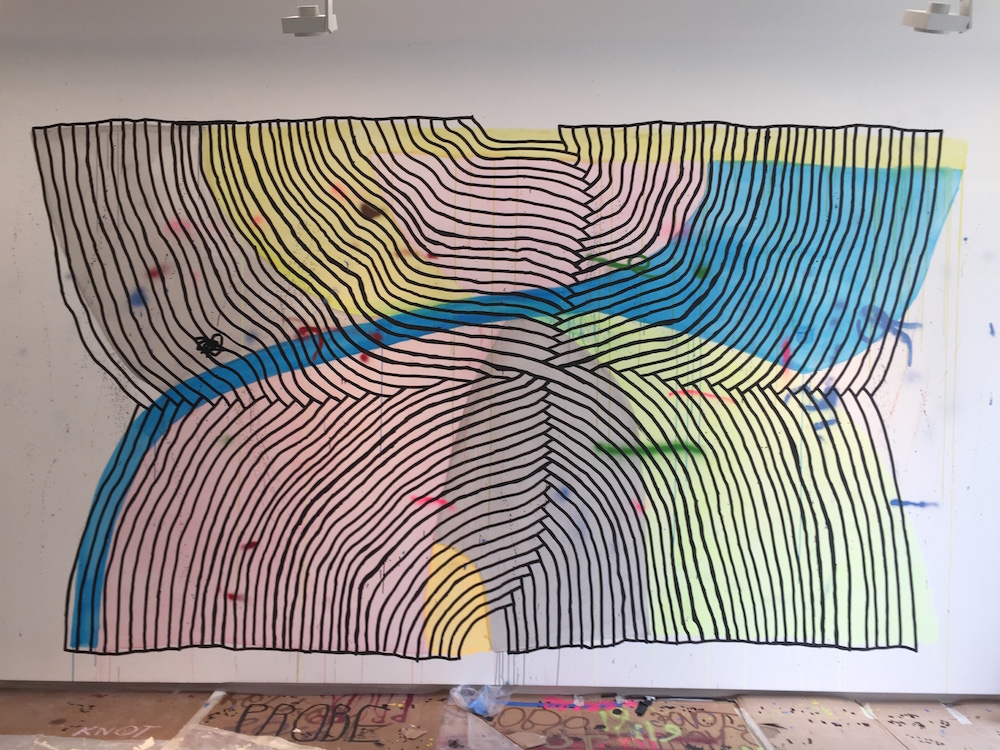

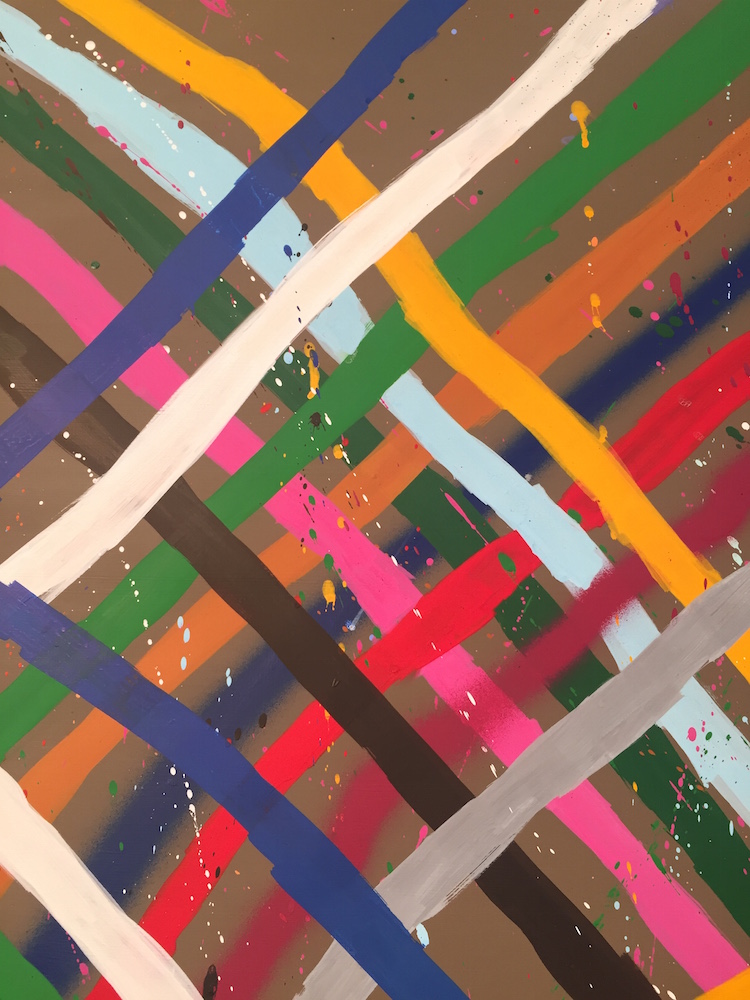

What does your process of constructing your work looks like? Do you pre-plan the motives, the weave, and all the elements that you incorporate?

There's a pretty simple pattern, but there are unplanned parts. The color bands, I start with one color, I start with one line. I mix a color for that line, then I go back and I mix another color. And I never use paint out of a tube. There are always unique colors. And again, they sort of stand for individuality and how things work together. Not just humans necessarily. To be honest, it's sort of like adaptation, in a way. Well, we are nature, so it's more nature-based, including humans.

The work comes across, at least to me, very honest and very direct.

It is what it is. That's what I like about it. And I have to accept certain parts. That really drives me nuts. But again, I think that's part of life. I always see one or two lines that really just irritate me, as the bad mood or the thing I shouldn't have said. You just have to move on, no regrets. The neat thing is it's just one line and as the piece grows, it gets lost in all the other ones. So again, there's that metaphor. I learn things about being out in the world from the work.

What about the use of found materials and different types of paints? Did that emerge as a necessity, as in using whatever was handy, or do you try to mix different things?

It came out of me not liking to shop, and I don't like new things. It just felt unnecessary to buy canvas and not very inspiring, to be honest. So, when I find wood, I never alter the sides or cut it. Also, I see it as a collaboration. I see all materials as a collaboration. So sometimes we can figure it out, me and the wood, we can figure it out quickly, and sometimes I have pieces of wood that I've had and I love for a decade.

I like the idea of working with something that somebody threw away. Not in an, "Oh, I'm going to make you special. I see you," way. It's not that. It's just more interesting to me, and I think I kind of relate to it. It's in that same way that I don't necessarily like shopping for clothes. I know I have to do it, but I don't want to have to spend a lot of time.

Is it, maybe in some way, kind of a statement for or against the modern technologies and modernization, in general?

It's not even that thought out. I'm actually not someone who's premeditated about anything, to be honest, except for commitments. If I commit to something, I'm going to follow through with it. Only recently, for the first time, I flaked on something that I originally committed to; it was a small thing and I just couldn't do it. So, no, I'm not somebody who had a plan or anything.

I was thinking about that because, in the early days, you were all activists and kind of punk-orientated, anti-establishment. I think that can still emerge in the works, but maybe you don't feel that way at all?

I mean, sure, in my twenties, I was often angry about a lot of stuff and now I'm pissed off and angry about other things [laughs]. I was just growing up. I was too scared to go out with Barry McGee and all of them. So, a lot of what I did on the street, in the beginning, would be just to go out with my beautiful dirtbag friends who never painted. But when I'd go out on my own, I would go to corporate buildings and do this pockmark. I considered it diseasing the building or exposing the disease that was this corporation. I was just immersed. I did a street theater festival in the Tenderloin for ten years with The Luggage Store, and I've done free workshops with kids and teenagers for years and years and years...

I think it was just part of life and the people around us; it was just always being active. We did political musicals, dirt bag style, in abandoned buildings. We took over a building in mid-Market Street in San Francisco for three months and had free meals and everybody painted on the walls and it culminated with a bunch of bands playing, just things that were able to happen back then. I assume the young kids do that still. I mean, I actually know that they do.

Maybe this is a bit too romantic, but do you think it is possible nowadays for something like "your scene" to rise up and happen?

Sure thing, absolutely. One of the things I will say that is different about my experience then and the kids that I work with now, and maybe it's a financial thing and partially gentrification, but there's no stability in housing for these 20 year olds. I mean, a room is $900. I have a bunch of graffiti friends who find these run-down places. It still can happen. But kids are really scared about graduating and real life. And man, I couldn't wait to get going, you know? It's a real stark contrast. And maybe I didn't have debt, I didn't have my parents pay for art school, but I had scholarships and worked my jobs. Some of these kids, when they graduate, there's a very quick separation. There are the ones that will work whatever job, live wherever to make their work and then there's the others who go back to mom and dad's place because rent is a hard. But, I never thought I'd have a different life than working a job and making my art, and not in a way that I wasn't seeking something out, but I like to participate in what I benefit from.

I didn't ever want anything different and I try to not to be as dependent on things to make me feel a certain way. So that, I will say, is a difference. Or they're freaked out about wanting to get a gallery. And I'm like, "Don't think about it. Make your work." If you create a strong relationship with your work, nothing else is going to matter, and that's honest work.

It's often mentioned that your work has these personal marks that you leave around, like coffee pot stains or shoe marks or fingerprints, maybe even some text written. How does that happen, and are they ever directed to someone?

It's the way I keep it loose. I literally just throw shit at it, but the ring marks come because I'm drinking coffee while I'm painting, or I'm drinking a glass of wine while I'm painting. People have given me shit through the years, like, "Why aren't you more precious about your work?" And I'm very precious about my work, but that doesn't mean I want it to be clean or not touched. I'm the one who's always getting yelled at if I'm in a museum because I want to look so closely at the work. I actually want to touch it because I'm a maker. I understand that can be disrespectful, but it's a very tactile thing for me with my own work. It's not just how it looks. It's literally how it feels to me.

I'm always sort of jealous when I speak to artists about their work and then they go over and really touch it. I'm always like, "Oh, I want to do that," but it feels wrong.

Yeah, you can always touch mine. I'm a total slob, but it's a part of the process. I don't mind dealing with things that are out of my control and seeing how to work with that. I don't want to be scared or dependent. I want to be flexible and be able, whether it's art or whatever, to just be open. I always say it's like my imagery moves embarrassingly slow; but I'm also personally satisfied. And I think because it moves slow, I've never been bored. Never. Not once. Not just in art. It goes right to annoyance, you know what I mean? That is a very elitist thing I think, to feel “bored.”

When I hear my friend saying, "Oh, I'm so bored," I think, "How the hell can you be bored in this day and age?"

These people are also very lazy about language. I'm a very literal person and I get bothered by people who use certain language, and it's getting worse. "I'm just so depressed." It's like, "Do you know actual fucking people who have depression? That's a very real thing. You're just a brat." You know what I mean?

"You're just moody."

Yeah. It's just another elitist thing. There was a time where I felt like I should leave the Bay Area thinking, "You can't be that person who stays here your whole life," and then a few years went by, and I was like, "No, I want to be that person." Why would I leave something? It was like that: "You should leave!" but I never wanted to. I never felt like I wasn't growing. I never felt like I was unhappy. I never didn't want to do what I was doing. I mean, there were times when I hid a little too much. I had a phase in my life where I had to work some things out with myself, but then I remember thinking, "No, I actually really want to be that person."

And there's nothing that's telling me I shouldn't be here, and to be honest, I've made... I'm going to cry again... I've made a really great life. I feel very lucky Sahar [Khoury] and I made a solid life for ourselves. We own a house now in a way that happens so randomly. It was a house that we actually rented for years and went through foreclosure. I feel very grateful and I kind of can't believe it. I'm also sleep-deprived.