Aleah Chapin

In the Flesh

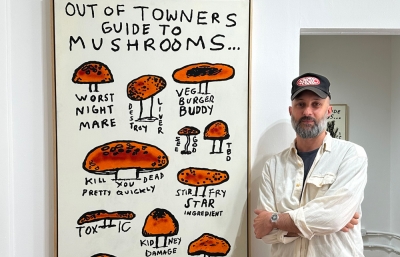

Interview by Doug Gillen // Portrait by Chris Rodriguez

When acclaimed figurative painter Eric Fischl declared Aleah Chapin “the best and most disturbing painter of flesh alive today,” the praise was like an inside-baseball reference to the way artists often appraise each other’s technical skills. Hailing from the Pacific Northwest, Aleah Chapin paints flesh with such hyperreal palpability that the figures seem to breathe through the canvas. With a series of abstract and bold brush strokes that reveal surrealistic visions, especially in recent works, it’s clear that Chapin is a rare and evolving master.

Shooting into the spotlight as the winner of the UK's 2012 National Portrait Award, Chapin quickly transitioned from New York Academy of Art graduate into one of the art world's most hotly anticipated rising stars. Her Aunties series was a celebration of mature womanhood, a brave and forceful portrayal of the female body in art. Within a traditional framework, these paintings, steeped in realism, invite insight into the lives of older women and their intimate, often playful relationships. When Covid-19 descended, our group engagement shrunk into selective cocoons, and with that, the creative direction of Aleah's work shifted. Through a series of streams of conscious, cognitive exercises, Chapin retreated further from the perfectly rendered forms signature of her craft in an attempt to re-examine and rebuild her identity.

With her 2021 exhibition, Walking Backwards, at Hong Kong’s Flowers Gallery, she debuted a new style that excised the characters and subjects that had populated her paintings as she drew inward in her journey of self-reflection. And here we find Chapin in this wonderfully complex evolution.

Doug Gillen: Clearly, within the last three years, though it feels like three decades, we have collectively experienced global, pivotal, historic moments. As you create, how does the rest of the world play in as a factor? Or do you instinctively try to shut yourself off and erect barriers?

Aleah Chapin: Definitely no barriers. No, it comes right in. I feel like it's actually my way of processing. I don't think I do it literally. I'm not thinking, "Well, now I'm going to paint paintings about abortion rights." I'm a very sensitive person and I really soak things in and feel things. I think beauty is a complex word, but if I don't create art from it, create some sort of beauty from that, if I don't create something from how I'm feeling, it's going to get stuck inside me and I'm going to get sick. It's going to be really bad. So I definitely feel like it's the responsibility of the artists living in this time to be a mirror, a sieve, I suppose. Things come in, and then something else comes out. That's what our responsibility is. At least that's how I feel.

This is the job that you seem to have taken on. When times get tough, we turn to artists for some sort of way to process what's going on.

I suppose so. I just feel like I don't have a choice. I feel like I've been an artist my entire life, so I have no choice. I've had moments where I've thought about doing something else, but this is the thing I'm meant to do. And this is just what happens; stuff comes through when I'm open in the studio, especially with the new work. I think the work that I'm more known for, like the Aunties project, felt a little less of an immediate, like, "This is what's going on, and I'm feeling these things, and they're coming out." But the new work I've been doing since Covid has been a lot more about that. It's very personal, but I'm a person living in this world, soaking in the world, so what's going to come out is probably going to be a reflection of what's happening. My hope is that, through me just trying to process everything going on, someone else might benefit and I could help them handle what they're feeling because we're all feeling it. Wherever we are in the world, everyone is going through some really intense times. So, I don't know, it doesn't feel like a heavy responsibility. It feels like, "Oh, thank God I've got this way to process it," because otherwise, I don't know what I would do.

I’ve been following your work for years and what feels particularly right to address now is the idea of this change. I don't see it as often as I would expect to. It's arduous for an artist to build a brand, for lack of a better word, to build an identity—and then to just be able to…

Shatter it?

Exactly, or kind of release themselves. Let's start with what was the catalyst for you moving away from this more traditional figurative work into your interpretations from the last two years.

First of all, thank you for wanting to talk about this new work, because this is really where I am right now. I think there wasn't one moment when it happened. I feel like it was just that this unsettled sense entered my own work for a few years before the change happened, before the work changed. I was just feeling… I have no words for it. It just wasn't feeling like me anymore. And I was feeling like I was literally painting myself into a corner. Let me just say, I love that work. Of course, I struggled, but I'm very proud of all of it. I feel like it's done some really good things for our culture, and I'm incredibly honored and humbled to have made it.

But as a creative person I need to follow my own inner “something.” And if I don't, I can't paint. I can't make good work. So what happened is that when Covid began I had been doing these really quick, sloppy, “bad paintings.” I just say that because they were coming from a very realist place. I don't think they're bad, but coming from such a realist background, I needed to have that in my mind. Like, "Aleah, just make some bad work here," to free myself up. I was just making these really loose painting sketches in my studio on paper, just to get something out because I was feeling so constrained by what I'd been doing and the way that I was working. So yeah, Covid happened, everything was canceled, and I had the freedom, space, and time as the world was ending!

And so why not change? I mean, everything's changing, so why not change myself? That's where it all started. And then I've really just gone from there. I'm continuing and we'll see where it goes. But I have to say, I'm having a lot of fun in the studio, and that is amazing. Not all artists do enjoy all of it. I've definitely had times when it really felt like more of a job and I didn't want that to be my life; shatter what I had done with my career and continue on, maybe not shatter, but definitely shift.

How does the process in this more recent body of work, beginning to end, play out for you?

How these paintings start is me doing really quick, loose sketches with oil paint on gesso paper. They’re very intuitive, very quick. I might make twenty of them in a sitting. Then I look at them and see which ones I respond to. I'll take one of them and proceed to take photos of my own body in my studio with a tripod and a timer and take those. So I'm trying to get in the pose that I've found in the drawing, which is completely anatomically impossible. It’s actually part of the fun because unexpected things begin to happen with the photos. And then, I'll use something from that photo and I'll try to find some way that the photo reference can coalesce in an interesting way, and come together cohesively with the painting.

I sketch, play around a lot in Photoshop, and then dive into the painting, which is changing, of course, because I'm not trying to make it a copy of the Photoshop image, which is just my reference. I start with the really loose, painterly parts because I want the painting to be loose. This is where the paintings come from, more of an intuitive place. In the past, my work came from photo shoots I would do, and then I’d paint from them. Now the work comes from these sketches. I want the paintings to begin from these sketches so I begin with a really loose mark, and then build up the figurative and the realist elements, trying to find a synthesis in something that really works together.

You talk about trying to go back to something that was creatively pure, something untrained. Does that exist? Are these free expressive marks really untrained because of the way you make them, or are they, in fact, more informed?

I think that they can actually come from a genuine, real, untrained place. But they're not going to be that solely because I also have my eye which has been looking at art my entire life. That is definitely there. But when I'm making certain kinds of marks now, I'm, like, "I don't know what I'm doing. I don't know what this is, but this is cool." So it's definitely coming from a different place from the training. Using my non-dominant hand has really helped because something will come out that in the past I felt wasn’t good. But now I would say that it's great. Honestly, since I was a child, I was obsessed with realism.

Why do you think oils fascinated you?

Rembrandt, I think. I was just like, "Wow, look at that.” What I saw in museums was just the next level of realism. I wanted to get to that level, and thinking back now, it is the quality of paint, the surface quality, and what you can get… It's the most gorgeous material ever. I think I just wanted to know how to do that.

You're in Seattle, in your bubble, as you call it. I know you also lived in NYC and went to the New York Academy of Art. How do these city environments play out for you as an artist?

New York was amazing for me. I mean, that's where my career really got going. It was probably the best decision I've ever made, going to school there. I was in a small, amazing school full of figurative artists who were doing figurative work in very different ways. And then, being right in the center of the art world was an incredible experience. It was also overwhelming. I got very burned out. I was there for about five and a half years and by the end, I was a pretty anxious mess and had to move back to Seattle. But I graduated from New York Academy of Art and won the BP Portrait Award in June of that year, which completely changed my life. That was ten years ago, so the career just happened really fast and it was pretty intense. And after a little while I moved back to Seattle and still just paint, always paint, but less in the middle of the art world.

I was wondering earlier about whether you think it makes it easier or harder when there’s a personal relationship with your subject.

Well, it depends. Easier in certain ways because we both feel pretty comfortable. Harder in other ways because I don't want to hurt their feelings. I want to be sensitive to them and paint in a way that’s almost protective. And I definitely felt like, "I'm not just painting these paintings from me. I'm keeping my mom and her friends in mind." At times, that may have actually held me back a little bit because I wanted them to be happy with the paintings too. But they always gave me tons of freedom and they didn't want me to feel held back. I think that was a little bit of a struggle, as in, "They're going to see this. I hope that they like it."

One thing about the painting, Auntie, that won the BP Portrait Award, is that she is anonymous for good reasons. That reaction was pretty challenging for her and for me. Of course, plenty of what people were saying was good, but there were also a lot of pretty terrible things too that they said. It's the Internet. I mean, I'm surprised there wasn't more. And it was printed in newspapers. It was wild and we did not expect it. I should have expected it, but I live in Seattle. I guess I didn't know how big of a deal the BP Portrait Award was. It was challenging for the model, really challenging for her to be so vulnerable.

What have you turned to throughout this last period? Are there any particular references, artists, or otherwise?

I'm just always keeping my eyes open and seeing what's happening online, and also just in the world. I’ll always love contemporary art, as well as the past 100 years of work—and always, Rembrandt! But I'm definitely more interested in contemporary art these days. There's Agnes Pelton. I don't know if people know her. People should know her so much more. She was a desert transcendentalist painter. I’ve been really interested in female artists because there are so many good ones that just haven't been shown in art history classes, Judy Chicago, for one, I’m learning more about her. I just read her memoir and it's amazing. I’m really trying to educate myself on more contemporary art from the last 100 years and up until now, specifically, women. They have a lot to say and haven't really had the means to say it.

Does change feel less intimidating now?

Yeah, because the big change already happened. I took the plunge and now I can just swim where I want to swim and see what happens. It feels more exciting now. I feel like the world has opened up a lot for me creatively and that is the best gift I think an artist can receive from... who knows where? It's just the feeling of openness.