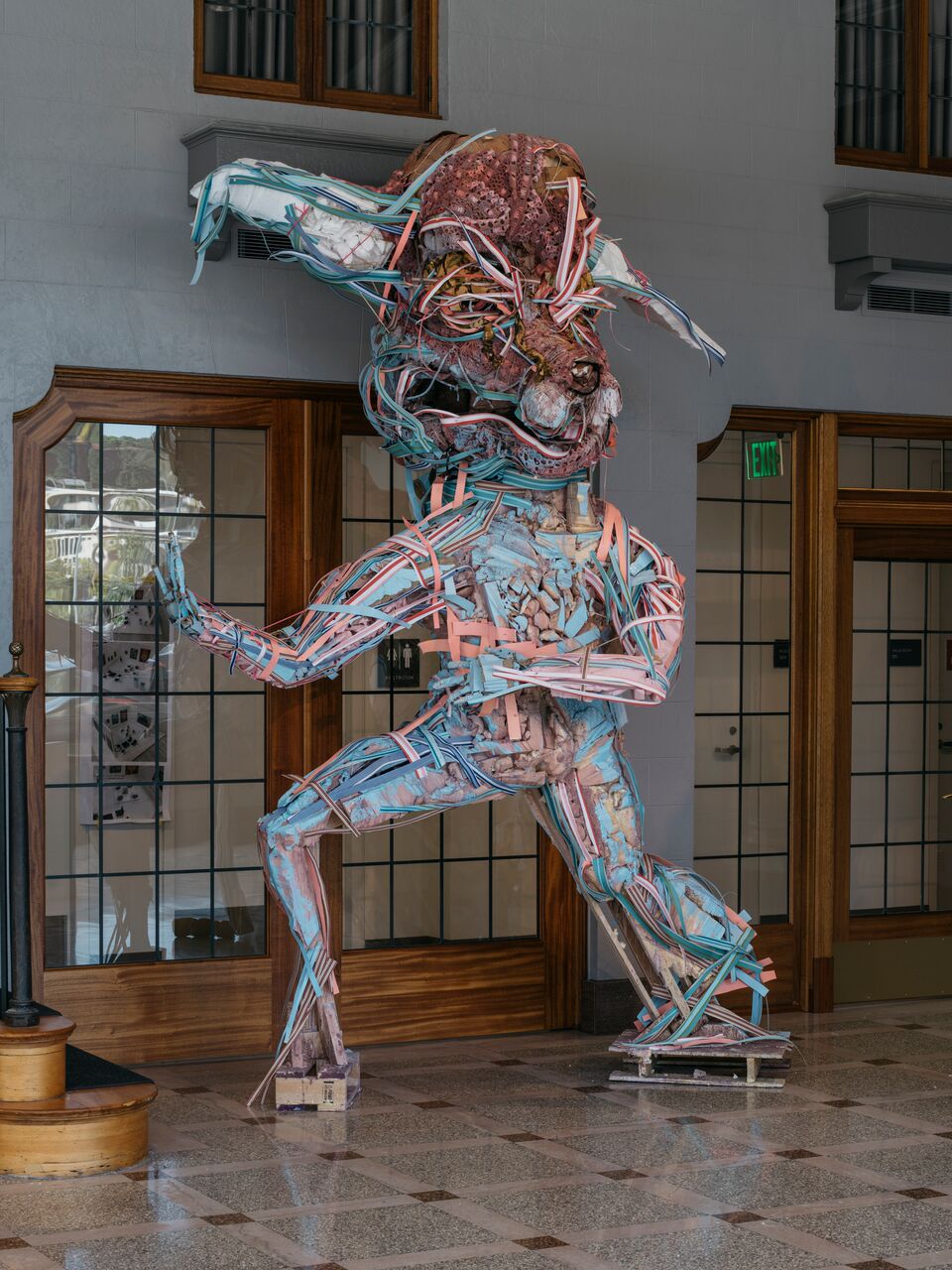

It shadows and hovers over the viewer and demands that one backs away from the work to take in its scope, but also, at the same time, up close, pulls the viewer into an experience of delicacy, specific intention, as well as a riot of formal encounters in the physicality and materiality of the processes that went into building the piece. —Elisabeth Higgins O’Connor

There are no better words to describe the impact of a colossal Elisabeth Higgins O’Connor sculpture aside from her own. Her resilient figures lumber into the world with a powerful clash of juxtapositions, comfy in their awkwardness and inability to hide, sweet and scrappy, steady and wild; they’re just like you. For anyone who’s ever had to bounce back or pull themselves up by their bootstraps, (e.g., everyone), these sculptures gently reach out and connect. They are alive with the history that made them, and their gestures suggest a triumphant rebound from whatever metaphorical pile of crap they’ve had to wade through. Constructed of familiar materials and towering precariously, you won’t know whether to hug them or run from them—an acute mirror of life’s everyday interactions.

Currently, Elisabeth Higgins O’Connor is likely singing and dancing to the music in her Seattle summer studio as she works toward her new crew’s debut in our Juxtapoz x Superflat exhibition at Pivot Art + Culture.

Read the full feature in the September 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Kristin Farr: What are you making right now? Seeing your process always makes me think of the lyrics to that Tom Waits song... what is she building in there?

Elisabeth Higgins O’Connor: Well, Tom Waits is definitely an influence! For this body of work, I have been working more from drawings and maquettes, building wood skeletal armatures and laminating foam insulation sheets into giant cubes, then carving them into the foundations for the bodies and heads. Previous work either accreted like a pearl, with bedding, cardboard and all manner of glues, drywall screws and paint, or were hollow, many-layered cardboard constructions, and had become prohibitively heavy, unwieldy, and after time, tended to deflate or deform during transport and storage. I normally work very intuitively, and will follow a form toward what it might suggest to me. Something that I perceive as dog-like might morph eventually into something sheep-like, for example.

Because of the time-crunch, new materials and processes, this work is forcing me to factor in more planning and engineering than ever before. The styrofoam may be peaking through in places, but will get layered with stressed or processed domestic textiles, scavenged cardboard and goo. It’s an aesthetic of buildup and erosion.

Portrait by Ian Bates

Is your use of the mule head shape mostly in relation to your fondness for Goya’s Los Caprichos?

The mule characters from Los Caprichos have been imprinted on me and I’ve been building a mule-headed figure in my work on and off over the years, ever since my undergraduate time in the early ’90s at Cal State Long Beach. I have always seen its use in my work as a way to describe a hybrid, something caught between two worlds, belonging to neither. I invite cross-cultural, universal interpretations of mule-ness, of course.

Was your recent sculpture of a mule creature falling down stairs a response to the space, or something else?

A mule-headed figure falling down an actual or implied staircase is something that I have built a few times in the past year and a half, initially as an installation response to the staircase at Suyama Space, Seattle in 2015. For me, there is an embedded element of the personal in the work, via psychological readings of posture, gesture or expression, but in the past few years, the work has become increasingly, although oblique and opaque, more autobiographical in nature... so yeah, it’s something else. The latest iteration may have this character splayed and sitting at the bottom of an implied staircase post-fall.

Do you call your sculptures creatures? Do they all have names?

I just call them “the work,” or sculptures! For many years, I referred to them and titled them No-Names, such as, No-Name #10, Blue Arm. This was inspired by Elliott Smith’s early song titles, like “No Name #3.” Then the titles evolved into words like Until, Because, and Otherwise—connector words in language that might allow the viewer to come up with a before and after.

The work is titled less generically these days and uses song lyrics, my own poetry or internal monologue, and pop culture references. They are fragmented embodiments or containers of my influences, intuitions, anxieties and history.

Photos by Ian Bates

Do the sculptures tell you when they’re finished? How much of your process is spontaneous?

There is a whole host of formal or conceptual considerations that need to be addressed before something is truly finished. Sometimes the work is “finished” because of a deadline! Sometimes there could be two or five “finished” versions of the piece layered and buried under what I’ve done. Art making for me is a process of finding and losing, finding and losing. I am happiest if both these events can be happening simultaneously in a finished work. The facial expressions are really important. When they read “right” to me, that part is finished. They need to elicit a certain pathos, and since I am generally using pretty clumsy, blunt materials to try to capture this, there is a lot of adding and ripping off of stuff. A piece is finished when it straddles a gap between opposing conditions; tenderness and the grotesque, lightness and darkness, sweet and horrific, and so on.

In the early stages of engineering a piece, I am forced to be more logical. I build the armatures with lumber, a nail gun, chop saw, power tools and ladders, but once the wood armature is stabilized and steady, the layering of materials can start happening. This process is like painting or drawing for me, and I suppose I naturally fall into more of a flow state of invention, intuition and play, following the piece’s internal logic, and delighting in my own.

There are elements of my practice that can be very satisfying for the zen and repetitive-task part of my brain, such as spending an entire day cutting floral motifs or stripes from stiffened bedsheets, or an entire day painting cardboard. There is a lot of preparation in getting to that spontaneity or state of flow. It is something that takes a while to build. It is not something that can be visited one day a week. It is about building a momentum with successive days, weeks and months with the work.

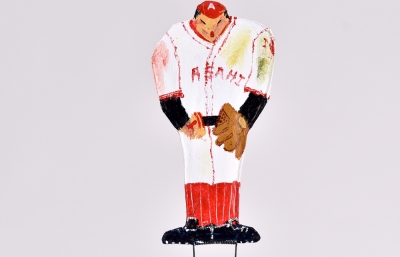

I do think of your work like drawing or painting; your paint is cardboard and fabric. Sometimes the materials seem thematic. How do you choose them?

I gather the fabric at thrift stores, and it is generally some form of bedding: sheets, quilts, pillows and afghans. There is an entire spectrum of texture, weight, pattern, fashion, era and color to be sourced, so there is a palette and an inventory of material. There is a language of the forlorn, the languishing, the out-of-step (style-wise and fashion-wise) in the castoff textiles. Like, really, who is going to buy that shit? That’s the stuff I gravitate toward. All the cardboard is found behind stores or on the street. Most of the paint is from the “oops” paint section at Home Depot or hardware stores, and then I might tint that with acrylic paint.

Since I generally work on a number of pieces simultaneously, I try to set up contrast in each one. One may be very floral, topiary, fecund, and its neighbor will be composed of only striped bedsheets, then perhaps the next will be composed of only doilies, afghans and knit materials. As well, an emotional component in each one will begin to emerge differently; rage, heartache, despair...

I do see it as drawing or painting: broad brushstrokes, graphic lines or pixels of color. Up close, a color field; step away, it comes into focus. I am doing a lot of restatement of lines or edges of forms and shapes with the material too. There is a lot of just looking at the work in the studio, having up close and personal scrutiny, affixing tiny elements with glue, thread or drywall screws, and then stepping back, walking around, or getting off the ladder to see how that passage “reads.”

Install for Juxtapoz x Superflat, photo by Ian Bates

Do you make big work to create a physical impact, or do you just love it?

I enjoy working, period, and I have been lucky to have gallerists, dealers and curators invite me to fill spaces. Could I work smaller and have the same impact on the viewer, and pack as much of a smorgasbord of content into the work? I don’t know. As the work decreases in scale, it becomes more precious, cute and doll-like, and I wonder about that. Does the small, cutie work diminish the power of the large-scale work? I do welcome the challenge of returning to working smaller. It’s a time thing.

The work that I am known for is large-scale, and has tended to be in the larger-than-life or twice life-size range, which is a disconcerting scale. It is a bombastic scale. It pulls on one gravitationally.

Did you have imaginary friends as a kid?

No! I have 3 younger brothers, we are all very close in age. We were a pretty bratty, rambunctious lot, we argued and fought a bunch, drew a lot together, made our own comic books, dug holes and built a treehouse among other adventures. We ran wild.

Were there any children’s books that thrilled or terrified you?

The original drawings by John Tenniel in Alice in Wonderland made me very anxious, very curious. They terrified me. That world looked intensely cruel. The illustration of the Mad Hatter and the March Hare shoving the sleeping dormouse into the teapot has stayed with me. It is so sadistic! And then my mother told me that the Mad Hatter had brain poisoning from the way the felt in his hat was cured. Ack!

We had that Time-Life Nature series and I pored over those, never got tired of looking through them. I loved things like Ripley’s Believe it or Not books and the encyclopedia. I was always reading things way beyond my years. I read Irving Stone’s biography of Michelangelo, The Agony and the Ecstasy, in fourth grade. I repeatedly read that. Also, all the Born Free books about the lioness in Africa, loved those. Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange in sixth grade, that was terrifying times a million, but I was fascinated with the language he invented.

Juxtapoz x Superflat installation, photo by Ian Bates

I’ve interviewed you before, and you talked about shantytowns being an inspiration, as well as the idea of being marginalized. What makes you relate to certain communities and structures?

First of all, I do not want to come off as someone who aestheticizes grinding poverty, but I do respect the ingenuity, absolute necessity and resourcefulness that go into building these structures. Making do with what’s at hand is a way of being that corresponds to how I work in the studio. I believe in a democracy of materials in my art making—materials that anyone can have access to. I save most of my floor scraps and studio detritus until I’m done with a body of work because the ideal scrap may be right underfoot.

I grew up and lived in southern California in working class neighborhoods for most of my life, El Monte, San Pedro and Wilmington, the L.A. Harbor. Right next to my grade school and junior high in El Monte was a 22-acre barrio called Hicks Camp. It was a dirt-street, farm laborer shanty town, torn down in the 1970s when I was a kid. I have very strong memories of looking through the school fence into Hicks Camp. It was a little island or vestige of rancho life encircled by our a barely middle class subdivision just east of LA.

I currently live in Oak Park, Sacramento, an area that was hit tremendously hard by the housing crash, foreclosure boom, and a surge in homeless encampments. A favela-style structure is not foreign to these neighborhoods where I’ve lived. It might be someone’s carport, shed or unpermitted home addition. I am translating my own surroundings. Perhaps they remind me of the cobbled together forts and two-story treehouse my brothers and I built as kids.

As far as the concept of marginalization, there is an implicit social justice component in the work. The figures’ imperfections, the layers, describe a condition of being burdened yet burgeoning, peeling and covering, armoring and exposure, disruption and mending, cloaking and erosion. On one of many levels, these competing aesthetic qualities are a place that I thrive in; a history of buildup and takedown. On a another level, this kind of visual language is the language of the street, of marginalized materials and brutal processes. They stand valiant, yet are gravity-challenged. They slump and trudge, despite whatever has happened to them. I would never claim that the work represents the pain, anxiety and struggle for dignity that actual marginalized communities have to live with constantly. But I attempt to invoke empathy in the push and pull of horrific versus endearing. I make sense of the world through a lens of cycles and circles.

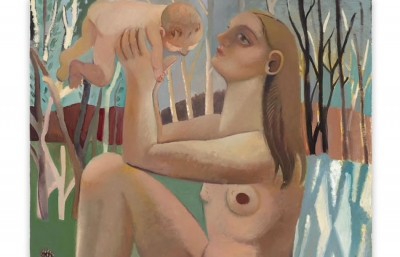

Through that lens, why do textiles hold meaning for you?

I respond to the embedded concepts these castoff household textiles carry: domesticity, comfort, childhood, familial history, birth, death, sex and dreamtime. They are all found at thrift stores, so it is very inexpensive material. I like that part! They hold different sets of meanings for other people as well. I like that certain fabrics could be compelling or repulsive, depending on who’s doing the looking. Textiles can describe droopiness and gravity easily. I’m interested in that kind of physical language. I think about the connotations of what verbs could mean in conjunction with bedding like ripped bedsheets, or patching things out of necessity or fashion.

Your pillow pile drawings are unbelievable. What role does drawing play in your work now?

Thanks! I had a studio right after grad school in an old gas station. It had a big space with two smaller rooms with large expanses of walls. I made sculpture in the big space, and hung paper up in the other rooms. I had berms of blankets, pillows and bedding piled up everywhere to put into the sculpture, and I had been making small drawings of thread and yarn and blanket scraps—the things that would fall to the studio floor—so I think it was just a logical progression that I started drawing the blanket heaps. Some of these drawings are small, rendered very tenderly in blue ball point pen, but there are also very physical, large-scale drawings, at least 80” x 100”, obsessively crosshatched in charcoal, chalk pastel and gouache. I have a desire to be really illustrative in my work, and the sculpture has been intentionally clunky, rough or awkward, so I think the drawing is a way to satisfy or dance with a certain crispness or clarity. I kind of see them as heroic portraits of really humble things.

----

Originally published in the September 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, available here.