When I ask myself to think of a brick, I quickly think of bricks. I see a wall— my mind’s eye fills the frame completely with the soothing geometry of brickwork, the patterning of deep reds and cement mortar— I can zoom in and out, but it’s all wall.

I’m seeing them in service, seeing the general functionality of an object without reverence to its materiality, to the umpteen trusted hands, processes, markets and social structures that enabled raw clay to arrive here in my mind as a vast and effortless wall. And there is thinking beyond this, to the delineations humanity has made, it’s keeping in or keeping out, and to the rubble of what is seemingly irreconcilable.

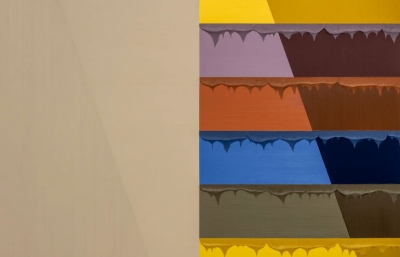

In our non-thinking and trying to think of bricks they rest in their purpose: stability. The art works in “Brick by Brick” subvert this notion in myriad ways, and in some cases, celebrate our use and reliance, dissident in bringing attention to an omnipresence.

In this deserving reconsideration of bricks, we could step our understanding all the way back to stars becoming meteorites and their contribution of iron in layers of earth— something we have in common with bricks, running in our veins. And yet we humans designed the brick based on our own bodies, making them the perfect size for a mason’s hand, freeing the other to trowel mortar. A unit built for human efficiency, yet showing the color of local clay in its body, a permanent reference to its soft, slick beginning in the earth.

Peter Hoffmeister begins as close to the beginning as he can get, is in the muck himself, doing the mining. At the sites of former and current brickyards he slipcasts from molds of the local bricks to create new ones. These bricks though, are hollow. As he distorts them, we still see where the right angles were, the contorted name of a manufacturer. The notations of usefulness are obscured and warped, and at first glance give a sensation similar to misbelieving there is one last step in the stairwell and letting your foot fall through air, unsure where it will land. These are unreliable bricks. Unreliable, Hoffmeister alludes, as the infrastructure that originally produced them on stolen indigenous land, building the mills of early capitalism, and cities that would reproduce the harm of marginalization. Should we blindly trust the brick? Matt DiGiacomo echoes the question in his solid, traditional brick, by simply inscribing it with the word “Chaos.”

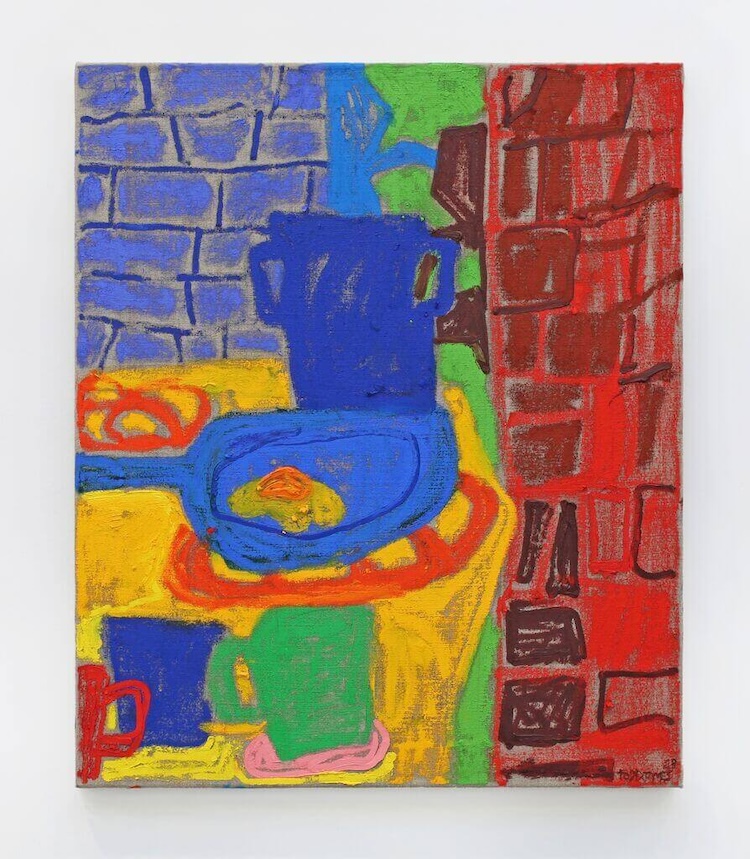

In one word, chaos returns us to nature, this place that’s been defined as separate from our built environment. Chaos is not a negative aspect of nature, but a reliable one. Ross Caliendo paints unmanicured landscapes in radiating colors of thick impasto, often cutting into the paint and making grids or straight marks that feel orderly and rigid in contrast. When the built structure of a wall or any reference to human presence enters his work, this is where we feel ill at ease, an interruption of a disorderly but working system, an intrusion on ecology. In Erik Parker’s psychedelic ecologies, where colorful forms interpretable as flora or fauna layer and intertwine, anything man made yanks us from his universe and is immediately recognizable as of our world. His use of framing gives depth to the wildness, and the feeling that it continues much further past our window into it.

Gustav Hamilton carries out a series of similar tricks. What looks like ceramic tiling is really a grid cut into a wooden frame for another frame, this one actually ceramic but organic in lush shapes of overlapping leaves. These glossy glazed leaves part to frame three separate spaces, two of which use painted brickwork to create dimension, drawing the viewer down into two respective holes— one the perfect shape of a bird, an impossibility for bricks, and the other offering a rectangular view of a canyon, another startlingly organic shape— each another frame for something beyond. In the third space, from a perfectly round hole, a flower grows from who knows how far down below, an iron red heart at the center of its petals. He alternately sets us up for softness or hard angles then delivers the reverse, keeps pushing us further. What is inside these pits, on the other side of these bricks, more tricks?

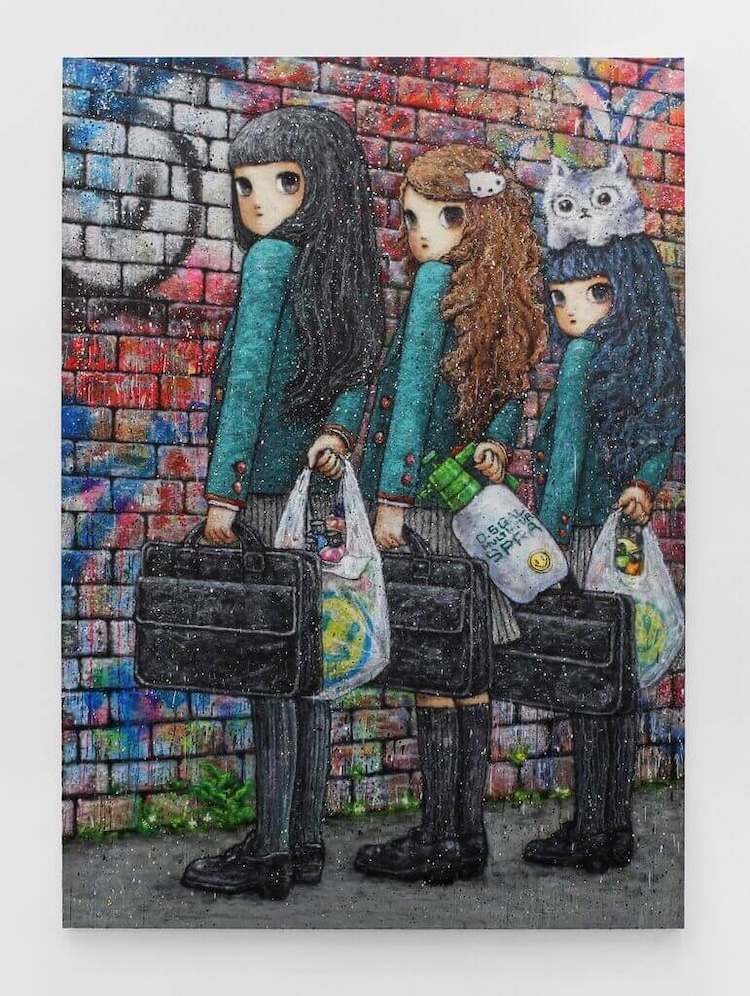

The trick of Nina Chanel Abney’s imagery is that it is “easy to swallow but hard to digest,” in her words. She embeds semiotics in her work, using the saturation of symbols in our visual culture to disarm the viewer. Known for large scale public works, there is an immediacy of messaging in her extremely clean lines, making for strong contrasts of color, the tool kit of graphic design keeping our attention and delivering commentary on race and gender. Before we’ve shaken the nonchalance of commercial imagery, we realize we are grappling with heavier subjects. Foregrounded in her compositions are bodies of color, and the tensions of representation and inequality. Like Stickymonger’s contribution, it is the human presence that gives meaning back to their setting. Three girls in their school uniforms, and uniform in their stance, stand in front of a colorful wall on which they’ve rebelled, paint in each of their right hands, opposing the briefcases in their left hands. The wall, the world; the question is how we will live in and with it.

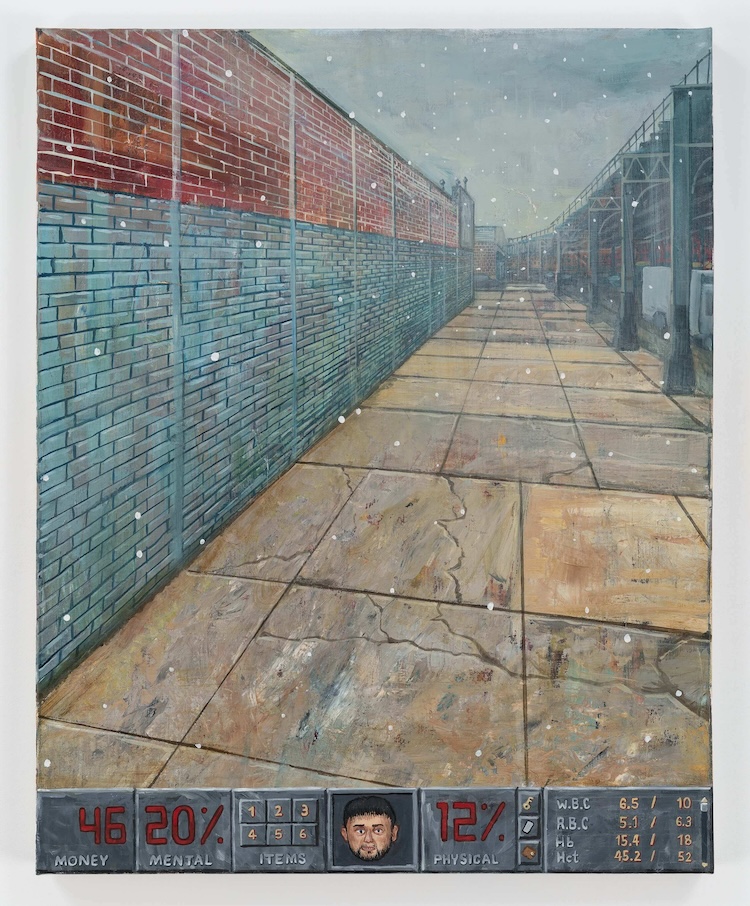

Figures in a cityscape can serve almost like a census, a recording of lives in a place, a recognition. Looking closer at an individual in a specific moment in their life, Stipan Tadic treats the brick like a pixel, building in paint a video game screen with a character whose stats show along the bottom. They are low. We see an icon of this character, and above his depleted units, we see what he is seeing. The cracks in the sidewalk echo the character’s vulnerability, as does the tall wall with no end in sight, the light snow and dusk. In this still from a traversion of a cityscape, bricks become ominous. The perceived permanence of the units that build the landscape are in reality corporeal, as withholding and impermanent as we. En Iwamura adds structure directly to a body like armor, wrapping his figure in bricks, from which it peers out. But even this resists permanence, a patina and graffiti tags on its exterior warrants the wary eyes of its wearer.

Masha Morgunova presents a more vulnerable figure, exposed, unsupported but lifted up on gray blocks at odd angles, broken from a whole. The artist admits to submitting to endless imagery of war, parsing through the rubble on her lit screen. Her figure cries from its entire body, letting one iron rich tear drop from the heart. There is care here, humanity bared but whole. The figure in Virginia Dudley’s (1913-1981) portrait is safe, enough so to pause at her window half disrobed, but with an air of melancholy. Dudley, a white woman from rural Tennessee, received a fellowship in 1943 to sketch and paint social and economic conditions in the South. The Black woman portrayed, painted in 1949, may speak to the challenges that persist even when housed in the seeming sturdiness of brick. Sixty years later, aptly named Real Estate Agent Going Crazy by Peter Saul from 2008, can speak to the subprime mortgage crisis, where millions of homeowners found themselves with property worth less than the loan they’d received to own it. We began with reliability, with a vow of the brick to protect. It is from this place that so many subversions are possible.

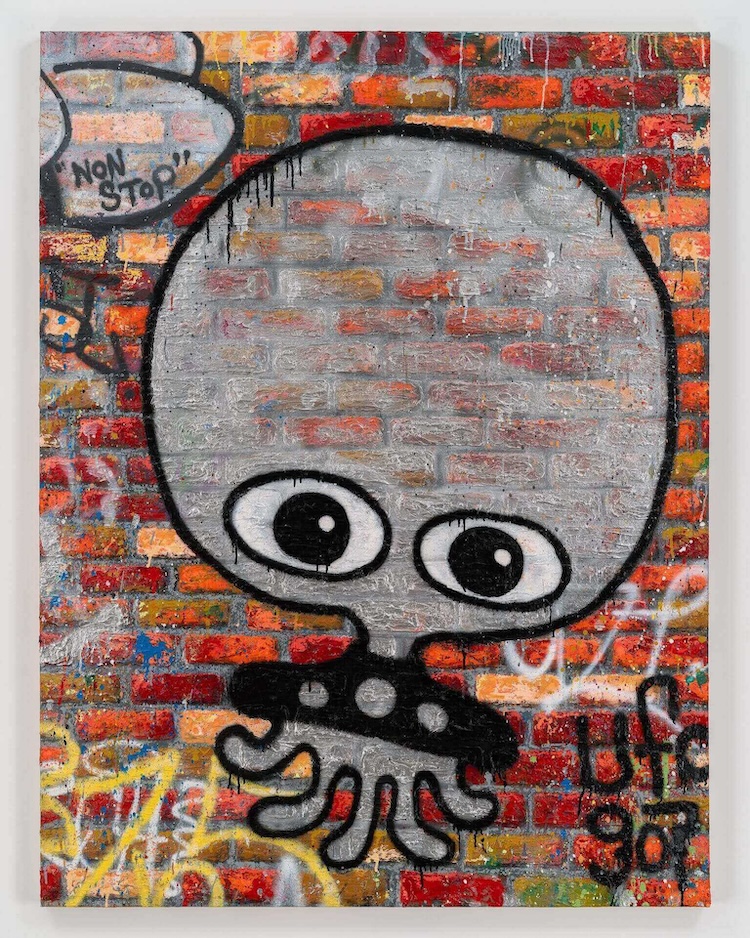

We’ve traveled from the seizure of nature, to the extractive process of mining, to commoditizing raw material, to building our cities and living in them. Artists like UFO907 stepped outside of structures and institutions to tag brick and concrete with graffiti, just to find their way back into the institutions of art, displaying that world on gallery walls. In the work of Todd James as well we see a reverence for graffiti culture and the effect of tagging, of claiming something for yourself that was put there for another purpose. The naming of your own presence in a place. It’s a celebration in Koichi Sato’s effortless neighborhood of soft brick street corners and facades, imperfect and curving, lived on, in, and around. The brick landscape envelopes a morning dog walker, all parties in warm tones at home with bricks, like the promise of hot coffee each day. Many of us rely on bricks, are grateful even, though the breadth of that gratitude may not touch specifically on the brick in their general prevalence, but broadly on the endless possibility of what brick can contain.

The life of a brick is not always linear, as stories most often are not. History is built year by year, but think of the wild variation in each increment. If that’s an analogy for a wall, then these standing histories all have their stories. So in the wall/time analogy, we must enter somewhere and embody ours. We remake, unmake, and include.

The artists in “Brick by Brick” each contribute an aspect of the brick to be considered as personal, a pause in the continuum of mining, firing, building, and rebuilding, to understand specific stories of a place, a people, or a person, as told through a ubiquity. Using paint, clay, and otherwise, these artists have made this magnitude of tellings visible, as artists do.

Inside of all this thinking I ask myself again to think of a brick. I now see myself, as you might yourself. We are singular units, perfectly and inherently unique, and yet mostly like the others. We come from locations, ancestry, traditions, are affected by processes and systems, and become a part of structures, of histories too. The brick teaches me about intention and about integrity. It also teaches me about potential. —Written for the exhibition by Emma Nicholas Young, contributing editor of the forthcoming Brick Journal