Harper’s is pleased to announce Library, Massachusetts-based artist Eliot Greenwald’s fourth solo exhibition with the gallery. In chemistry, the law of the conservation of energy states that within a closed system, energy cannot be created or destroyed; rather, it can only be transferred. This foundational principle plays a critical role in Greenwald’s conception of the environment and how humans and other forms of life engage with their habitats. For Greenwald, humankind cannot be distinguished from the landscapes it occupies—though they shuffle through diverging cycles of existence, decomposition, and rebirth, all types of life are ultimately cut from the same cloth. Across the works that comprise this exhibition, the artist reckons with such metaphysical relationality both iconographically and materially.

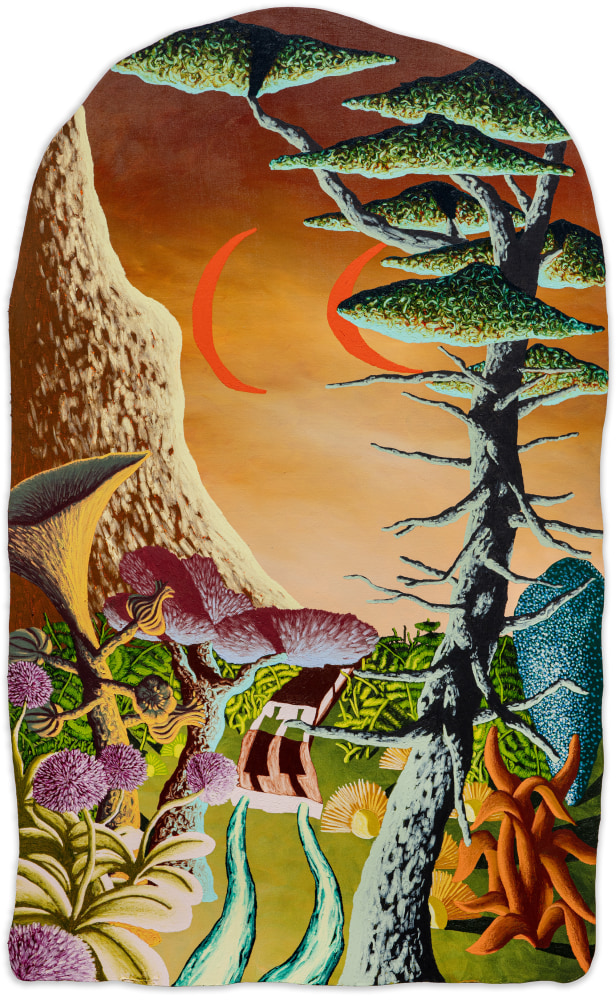

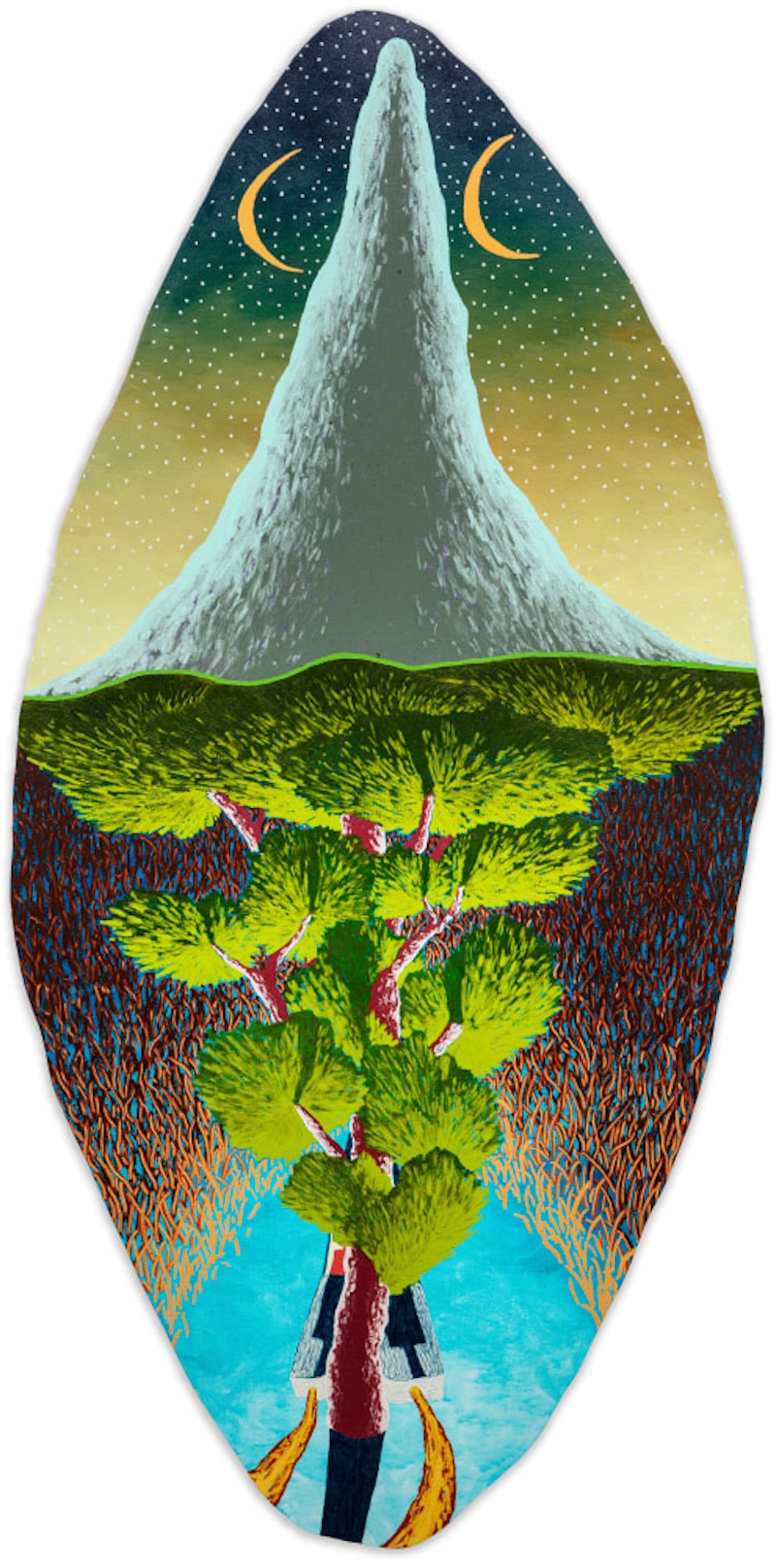

Visually, Greenwald locates the interconnection between natural and artificial worlds with an amalgam of richly saturated geological and botanical forms. In his surreal compositions, sinuous roads lead to towering mountains, often partitioned by identical crescent moons. Such is the case in the diptych A Letter to the Center of the Lake. Here, forest green mountains peak out from the rounded edges of an obtuse canvas at dusk. The magnificent horizon eclipses eclectic plant forms with frizzled tendrils and Jurassic branches. One grand plant ascends from the center of the work with meandering limbs, conjuring the famed tree of life itself. And like a pair of beaming eyes, twin moons watch over it all in phantasmagoric twilight.

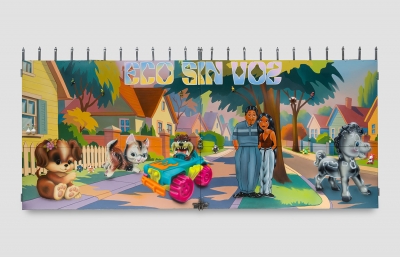

Greenwald returns to these celestial motifs throughout the exhibition, grounding viewers in the everyday ideographs of timekeeping that unite the world’s diverse ecosystems. But among these cavernous landscapes cast in whimsical hues, the artist also buries man-made inventions. Greenwald incorporates vehicles that cut through and illuminate the awe-inspiring terrain in these scenes. These miniature automobiles stand in for the human vessel itself—a subtle reminder that even the most engineered facets of the anthropocene are just one piece in the grander puzzle of existence.

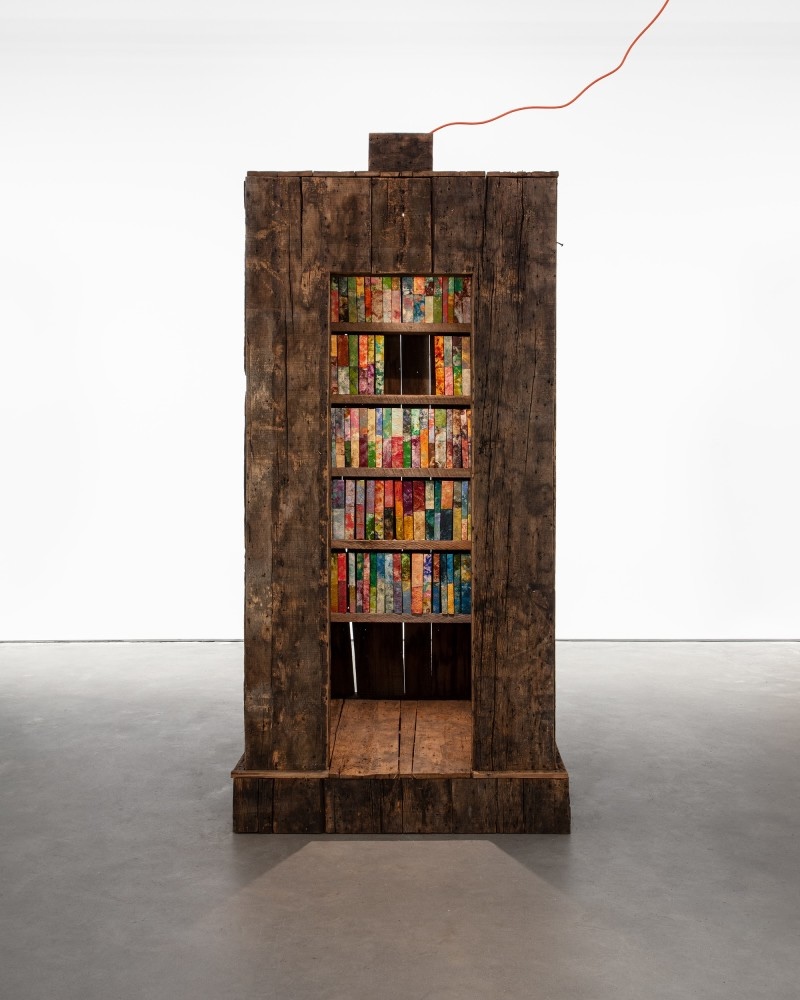

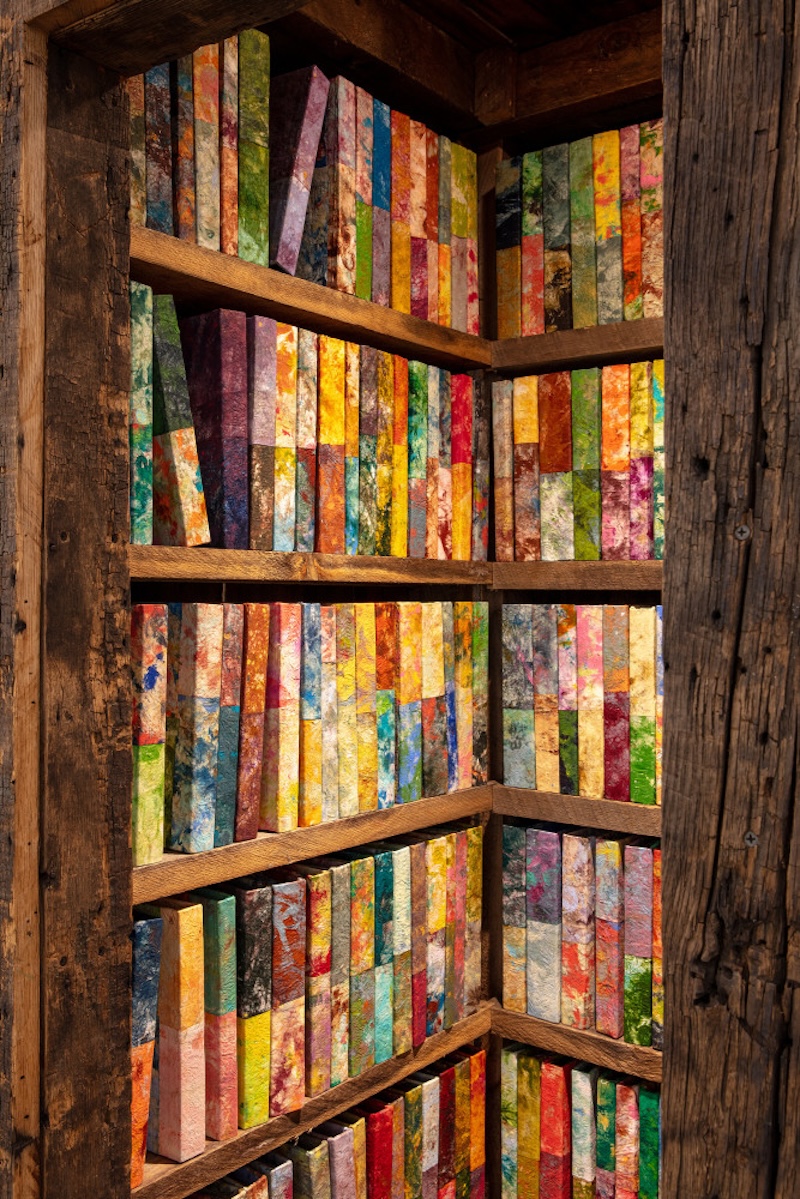

Library of Paper Towels furthers this existential reckoning by addressing the flawed yet enduring creations of human thought. Greenwald constructed this freestanding repository from reclaimed wood salvaged from an 18th-century barn in western Massachusetts. Inside, the hundreds of vibrant books that line the shelves are each hand bound by the artist, made from recycled paper towels used in the process of painting his Night Car series—a veritable index of artistic production. Together, the antique wood and fabricated books tease out the artifice of libraries themselves. With this sculpture, Greenwald probes at how knowledge is generated, disseminated, and archived.

Ultimately, Library is riddled with these kinds of playful provocations. Mining the tension between museal preservation and the byproducts of creation, the artist considers the ways in which cultural and metaphysical memory evolves throughout the passage of time. In this compelling presentation of new works, Greenwald embraces recycling and repetition as transformative rituals: it is through the act of reuse that one might uncover untold maxims obscured in plain sight—innate queries that speak to the confluence of communities and paradigms that erect life on Earth.