There are certain films that become outliers for their cult status, films that can be esoteric as well as universally appealing. If searching for an era, city, or cultural convergence to equal the massive historical clout of the late 1970s and early 1980s New York City, one might have to go back to the Lost Generation of Paris in the 1920s. Those years in NYC are pivotal for a myriad of reasons, not all of them art, but to look at the impact of hip-hop, graffiti, punk, break-dancing, club culture, uptown, and downtown colliding is to recognize that moment in history as a sort of BC versus AD of influential expressions. And if you need a film to help anchor the latter stages of the era, Charlie Ahearn’s independent and inventive Wild Style is your visual vocabulary.

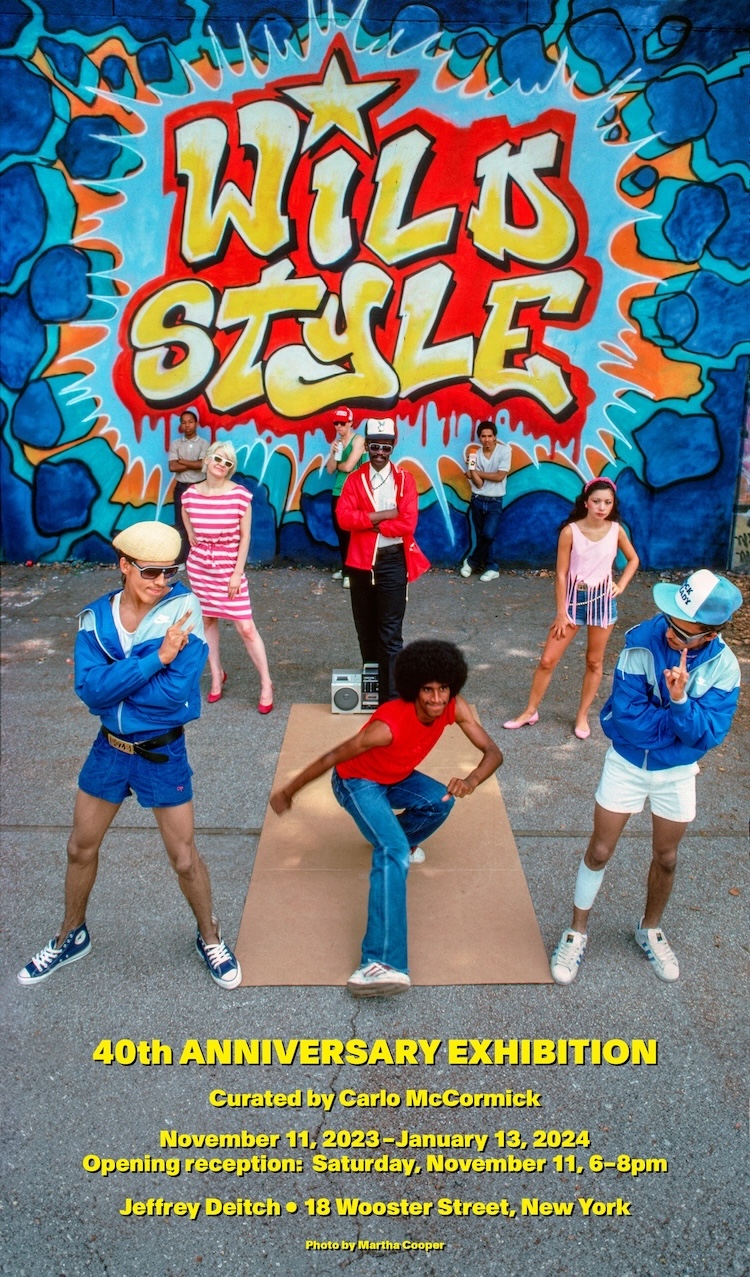

Hip-hop turned 50, Wild Style turned 40, and Juxtapoz turns 30. The significance isn’t lost here, where we look at the ways in which culture is disseminated, cherished, documented, and mythologized. Opening November 11 and on view through January 13, 2024, Jeffrey Deitch will host Wild Style 40, an exhibition curated by writer, critic, and NYC historian Carlo McCormick as both an ode to the film and a specific look at that particular moment in time. It’s a show about friendship and kinship, about a mecca of the arts at a time when the very definition was radically changing and evolving. “It never ceases to amaze me when strangers stop me in the street to try to explain how Wild Style changed their lives with their own personal version of coming of age,” Charlie Ahearn says.

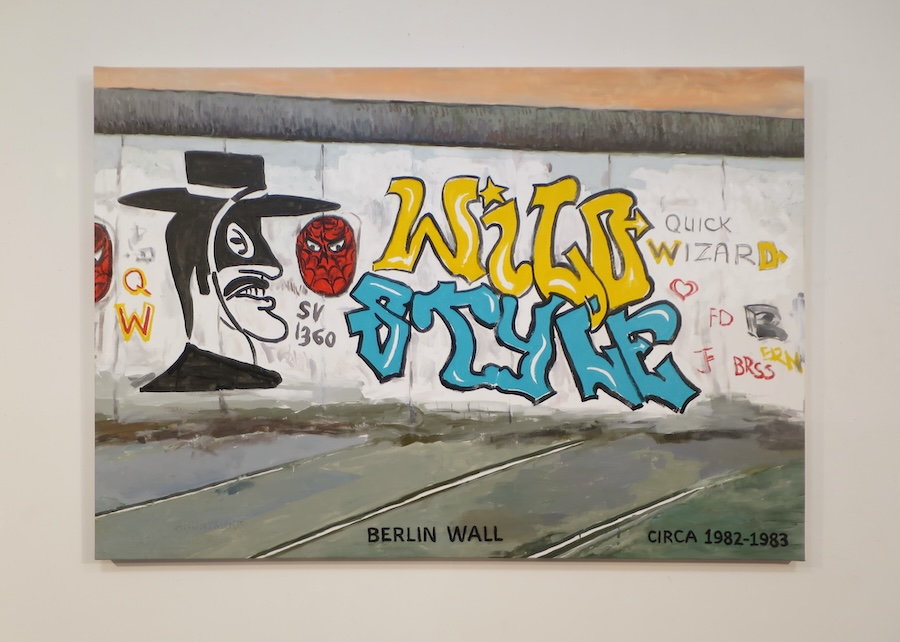

“Wild Style was not a documentary,” Ahearn told me over email recently. “It had to tell a story, and it had to be real. In the summer of 1980, trains were the cutting edge of modern art, such as FUTURA’s abstract Break car and FAB 5 FREDDY’s Campbell Soup homage to Andy Warhol. Graffiti writers were talking about wildstyle, a highly personalized lettering meant to be hard to decipher, full of sweeping blades and arrows, and the name ‘Wild Style’ seemed to fit the movie like a glove.”

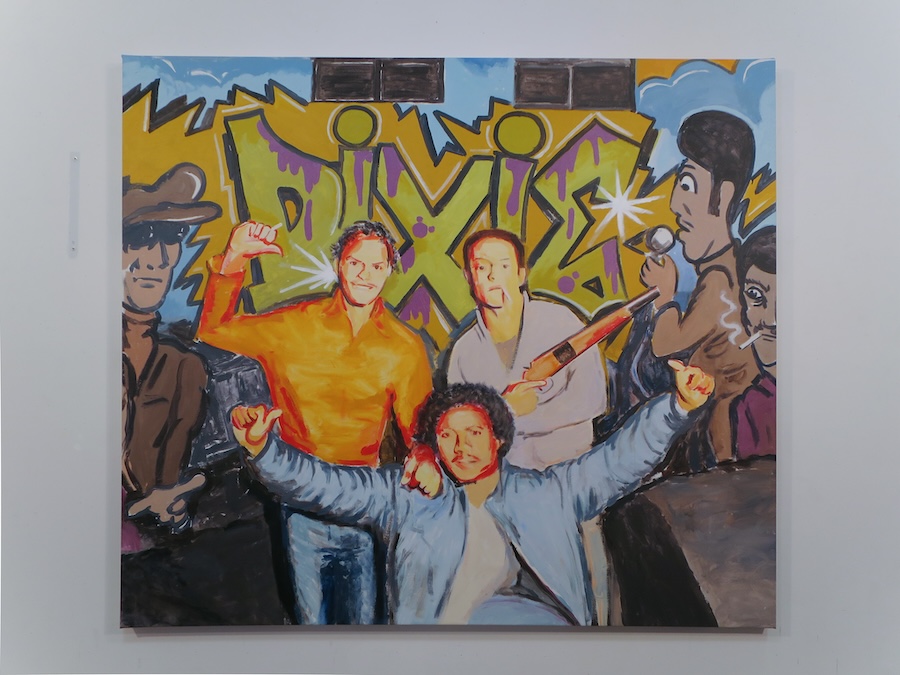

Real it was, but also proper cinema. What Ahearn was able to conceive of with Wild Style was something of an anomaly in the pantheon of films dedicated to street or underground culture. It was hip-hop, graffiti, and totally New York City. It was the 1980s, too, so it was very much a transformational decade for both NYC and America itself. Of course, there were actors playing roles, but those actors and extras have become household names in the arts community: LEE Quiñones, FAB 5 FREDDY, and Lady PINK, to name a few. Zephyr and Revolt helped make the opening animation. Ahearn’s wife, the artist and curator Jane Dickson, was key. As much as it was made for the screen, it was more than a film, as it helped create a personality for an entire generation that the rest of the world could identify and understand.

It also had the spirit of “indie” before the term of endearment became a staple of 1990s filmmaking. Ahearn actually adapted the screenplay as the film was being made. “The movie was always in flux, with me trying to build a stronger core to the story,” Ahearn says. “The whole film was conceived at one of the wildest art exhibitions, The Times Square Show, in June of 1980, with me huddling with Fred Brathwaite (FAB 5), talking about making a movie with hip-hop and graffiti and LEE. The idea was this story of an outlaw subway artist like LEE, although he didn’t agree to do the film until the last minute.”

There is an honesty to Wild Style that resonates, perhaps even more vividly today. That’s because no matter from which angle you approach the film, there is a camaraderie between the filmmaker and the stars that is palpable. One of the hallmarks of the early years of graffiti and hip-hop has always been that amidst the competition, there was a sense of a community growing and learning together while emerging into the mainstream as teammates. This was not lost on the curator. We spoke with Carlo McCormick before Wild Style 40 opened at Deitch’s 18 Wooster Street space to share his curatorial insights, Ahearn’s impact, and what living through the era of Wild Style meant to him. —Evan Pricco

Evan Pricco: As a curator, when you are approached for the 40th anniversary of Wild Style, how do you organize your thoughts and make “inclusions,” so to speak? There are a lot of things that could go into this show…

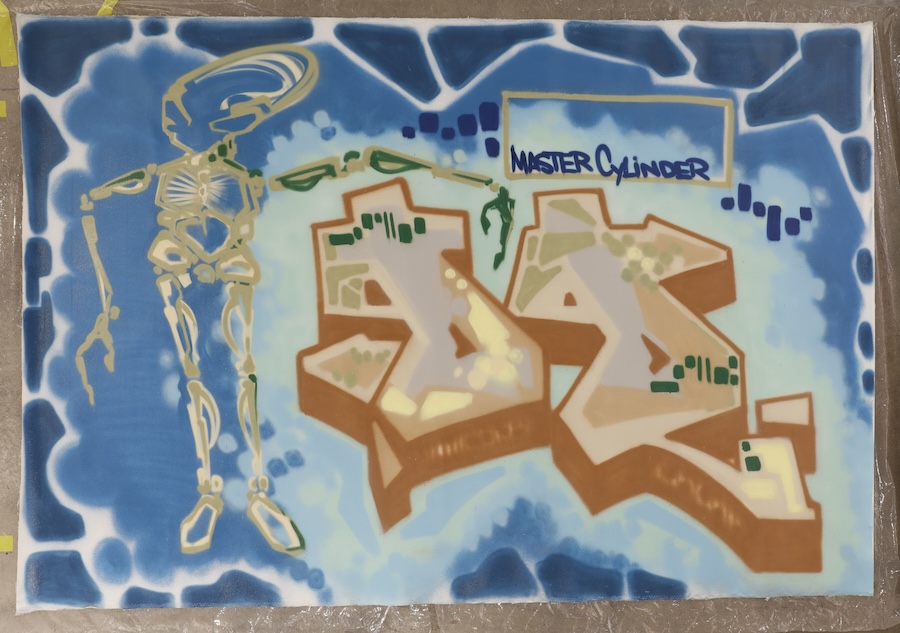

Carlo McCormick: It's kind of an obvious list in many ways. A big chunk of it is, “You were either in the room or you weren't.” I really wanted to kind of keep it friends and family. And then, you think about, "Well, how we're going to break those rules." So, we broke those rules by first of all, including both sides of the family, which is the Colab part, which Jane Dickson, Charlie, and John Ahearn, were part of. They did the famed Times Square show. It led to Fashion Moda—all these things that were coming out of the downtown artist community, which was politically and socially engaged. And then, putting it in with the people who are emerging from being writers into visual artists: LEE, FUTURA, DONDI, all that stuff. And then, how do we extend it beyond it? I really wanted to put Martin Wong in there because he was such a supporter of all these artists and of the whole culture. So, he's kind of foundational and really there in many ways. Which is why I wanted someone like KAWS in the show, as well.

I mean, the way it works out, which is kind of funny, is that it's a group show of people who, in 2023, would never agree to be in a gallery group show. Every single one of them would say no to any other group show. I mean, to a museum, they would say yes. So then it was like, "Well, it's Wild Style. Of course, I’ll do it.”

They all, in some ways, acknowledge how important the film was. And it also seems like a good indication that these artists acknowledge how important this moment was, too.

They’re all really young when the movie's made, but a lot of them have a history already. Like that wasn't the first time LEE painted a subway, as well as DONDI or FUTURA. But one thing that strikes me is that this was a time, not just in hip-hop, but where we were all kind of inventing ourselves. At that time, identity had a very different role because people were shedding their identities and reinventing their own. One of the great things about graffiti and why it still strikes my memory as the only time I've been in a race-free environment was because most of these people worked anonymously. So you didn't know if they were rich or poor, white, black, or Latino. You didn't know any of that stuff. It was just about their skills and how much they got up and things like that.

Wild Style is very much a downtown-uptown film, so that's a really crucial bit of chemistry that happens. Like at the Roxy or at Club Negril, or at the Mudd Club, or Charlie making this movie where downtown and uptown meet. It’s the kind of a cross-pollination that really fucking kicks ass.

Were you and the people you spent time with aware of how much of this cross-pollination was actually happening at the time? Or is it more in retrospect?

We were more aware of it then than we are now. If you look at the whole arc of the early 1980s, if you look at the crime rate of the city, I mean, it's a kind of statistic that will never be matched. New York's getting really fun again now, but it was really fucked then. And it's like at this incredible nadir of economic and social, it's just a whole collapsing infrastructure. But between 1979 to say, 1984, is when you're getting the white kids moving back to the city where their parents are going, “You know how many generations it took us to get out of that fucking hell hole? And you want to live there?” So it is a turning point, but it's really also a real nadir. It's just kind of a special moment.

Thinking of Charlie, when he was making the film, was he already quite known by the artists in the film?

He was and is a huge fan and a huge advocate. I really think of Wild Style very much like a love letter. He had made a few films by then, one of which was The Deadly Art of Survival, which was a super important film in the New York late '70s about the mythology of kung fu. He was definitely part of the downtown fabric, and then there were only so many people who were venturing up there to the Bronx. He went in there respectfully and early and met the key people, and they gave him a blessing. I mean, that's really how any of these things happen. That's how Martha Cooper ends up making her photographs and Henry Chalfant, too. You start as an outsider, and how do you do it? You do it respectfully, and then you meet certain people who become FAB 5 FREDDY or DONDI—people like that who are real. They weren't gatekeepers; they were people who opened doors and brought people together.

Wild Style 40 will be on view at Jeffrey Deitch at 18 Wooster Street in NYC through January 13, 2024

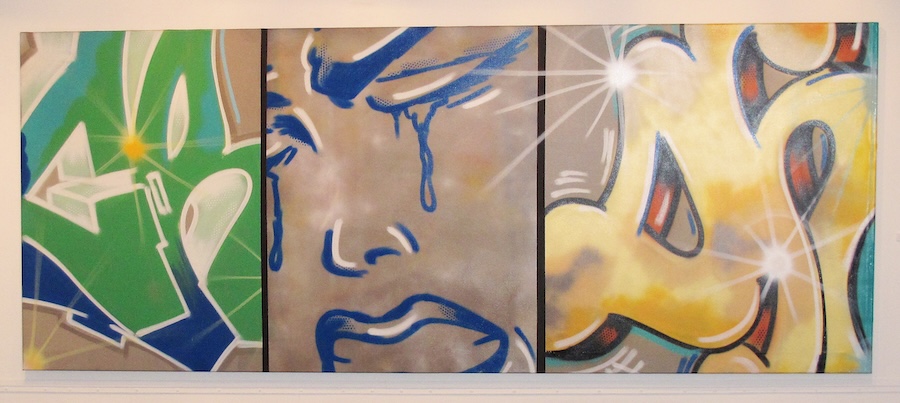

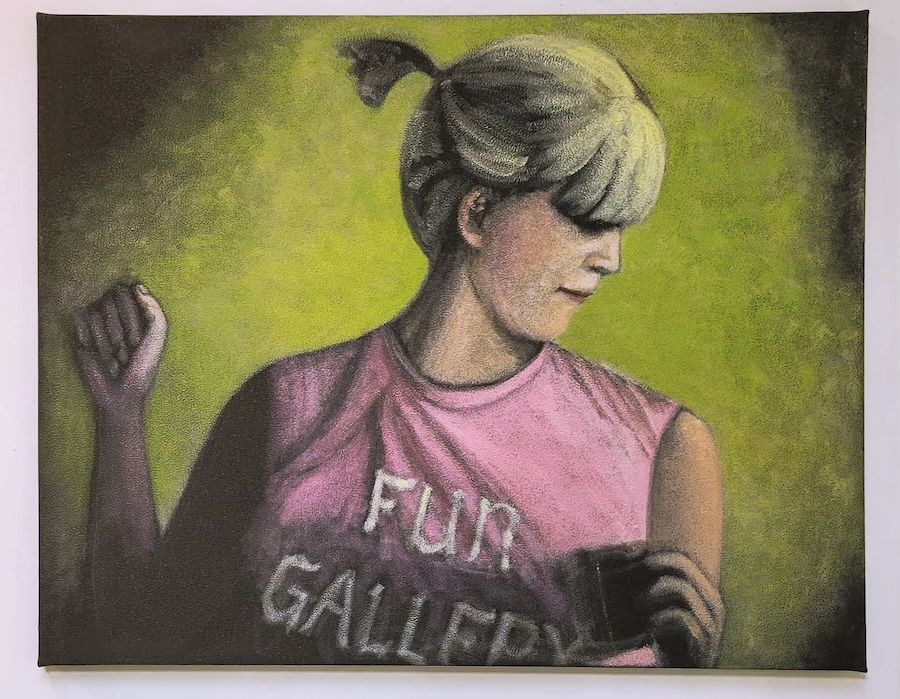

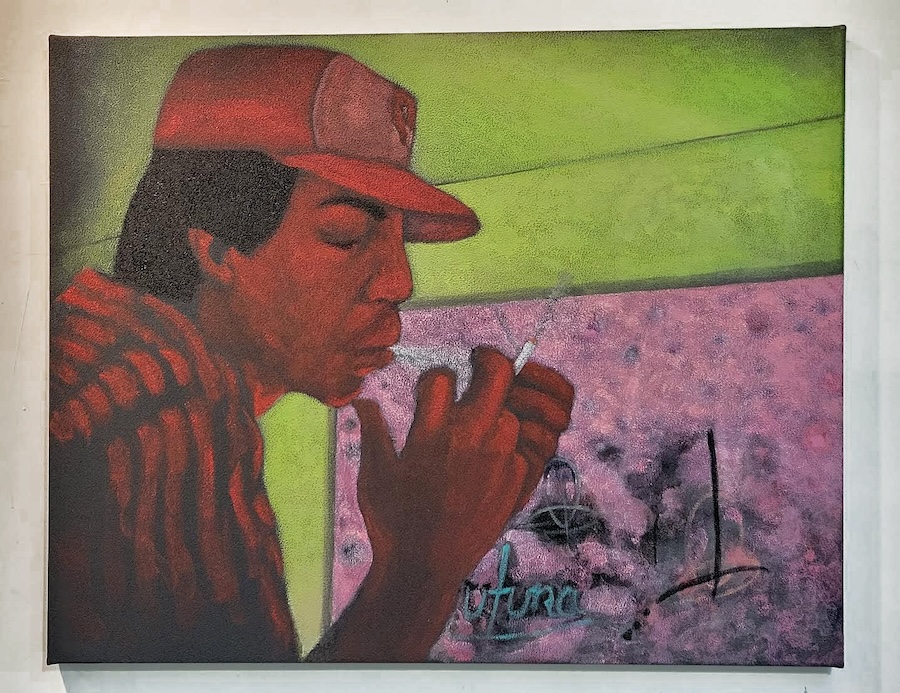

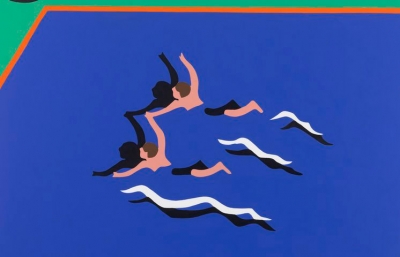

Artists included: Charlie Ahearn, John Ahearn, Janette Beckman, Fred Brathwaite (Fab 5 Freddy), Cathleen Campbell, Henry Chalfant, Joe Conzo, Martha Cooper, Jane Dickson, Brian Donnelly (KAWS), Chris Ellis (Daze), Sandra Fabara (Lady Pink), Aaron Goodstone (Sharp), Eric Haze, John Matos (Crash), Leonard McGurr (Futura), Osgemeos, Phase 2, Lee Quinones, Rammellzee, Revolt, Don White (Dondi), Andrew Witten (Zephyr) and Martin Wong.