The Isthmus of Darién, the center of modern day Panama, is a geographical sliding door. What is vital about its location is obvious in the development of the Panama Canal to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, as well as the connection of the North and South American continents within Central America. Three million years ago a geographical formation created the Isthmus, separating the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans from each other, but by the narrowest of lengths. For maritime purposes, the Panama Canal being completed in 1914 meant, symbolically, the reconnection of mighty waters, but perhaps even more significant was the conquest of man over nature. This was a man-made creation that determined how, who, and what could be closed and opened, and at what time, and with what labor and with what money, and who the Canal would serve. As such, Panama acts as a symbol of what man can do when it decides what kind of doors and passages it wants to control.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow'd Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

—John Keats, “On First Looking into Chapman's Homer”, 1816

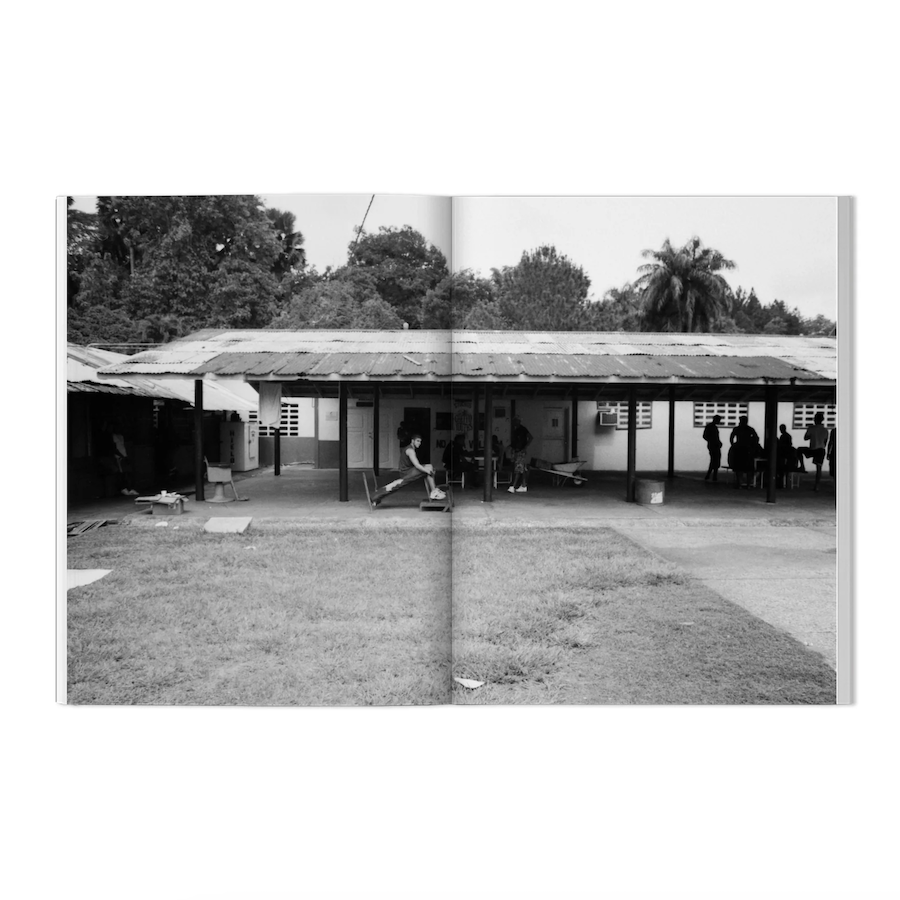

Perhaps these are the psychological conditions that make Panama’s incarceration rate one of the highest in the world, overcrowded with often poor conditions in the prisons themselves. The United States’ overthrow of Dictator Manuel Noriega in 1989 was a justification to combat growing drug trafficking operations, but in hindsight, what was to be expected? A canal built through a nation to provide easier trade routes for the East and West seemed naive to expect there would be no nefarious practices opened to the world. In turn, the prison system in Panama became a place to reign in, to hide, to overly penalize its population, a scar on the country that proclaims itself as a place where, literally, the world was opened up. So why close so many people off?

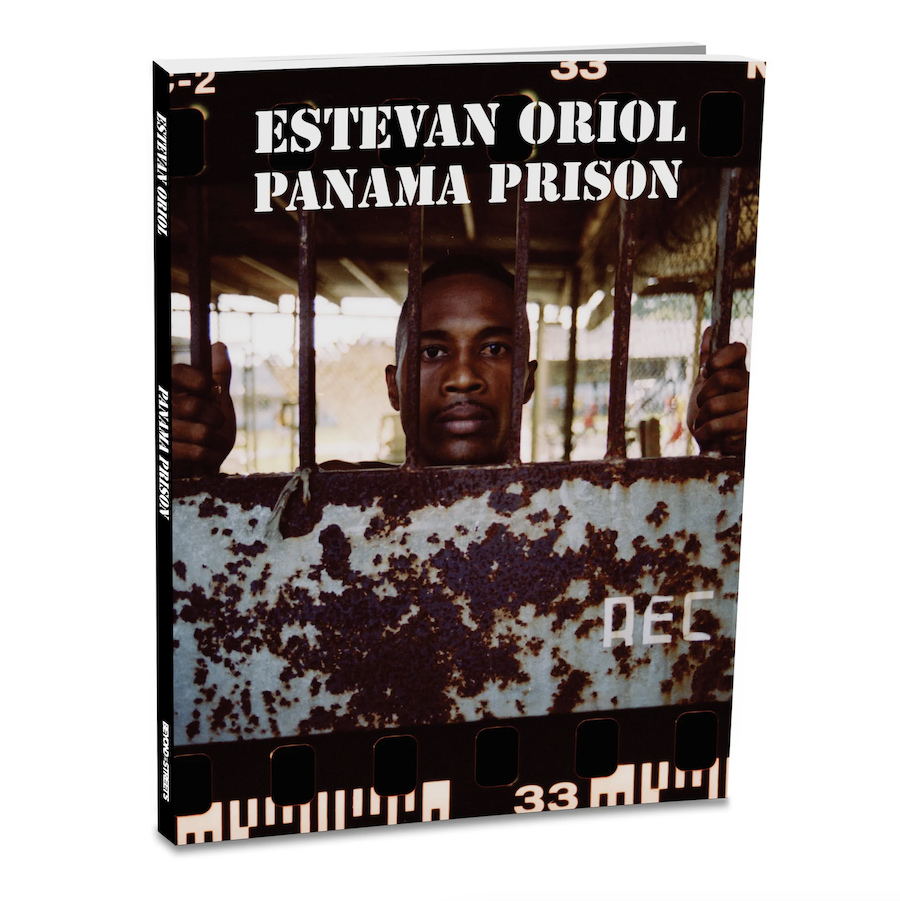

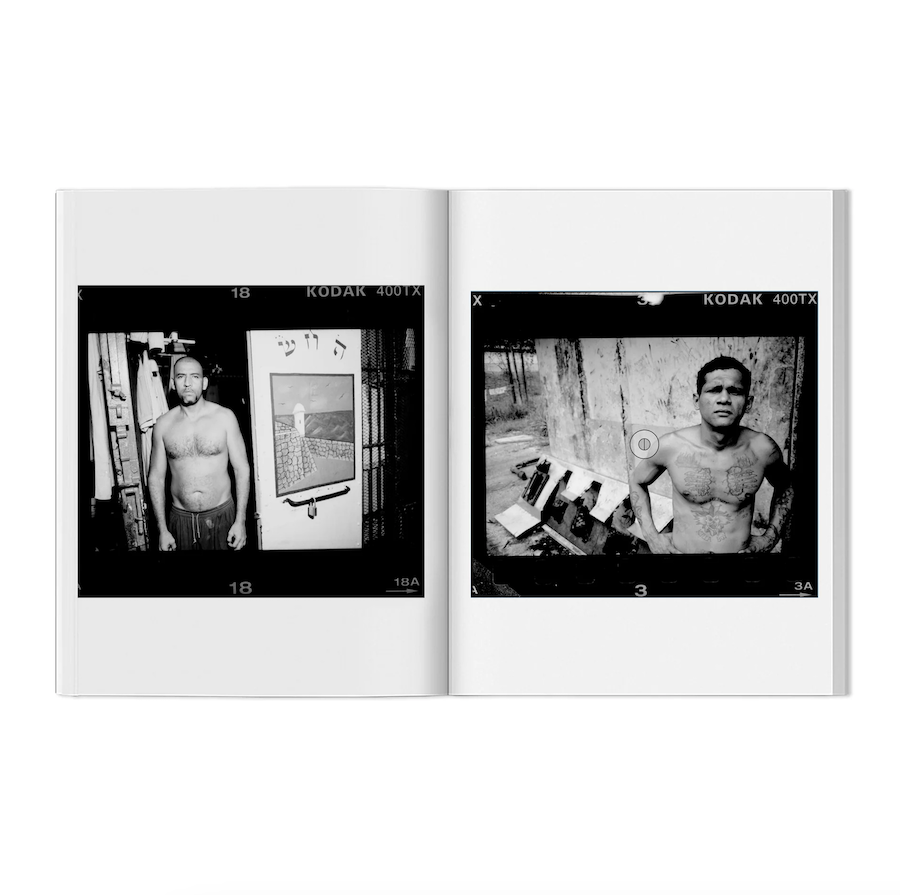

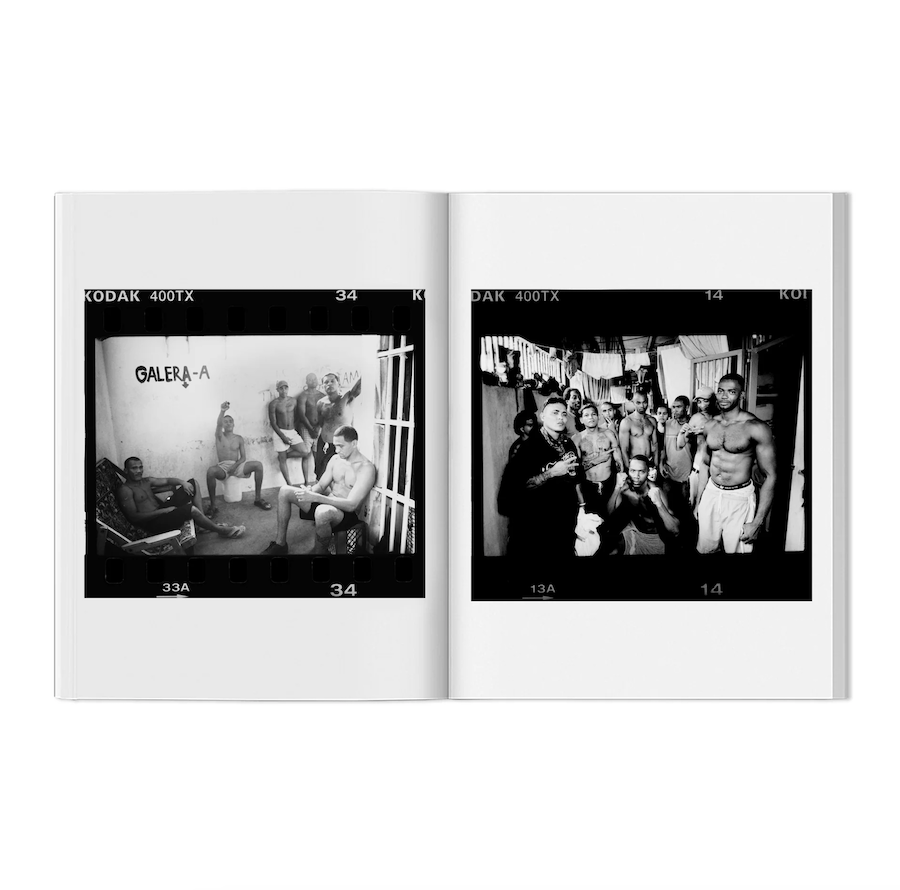

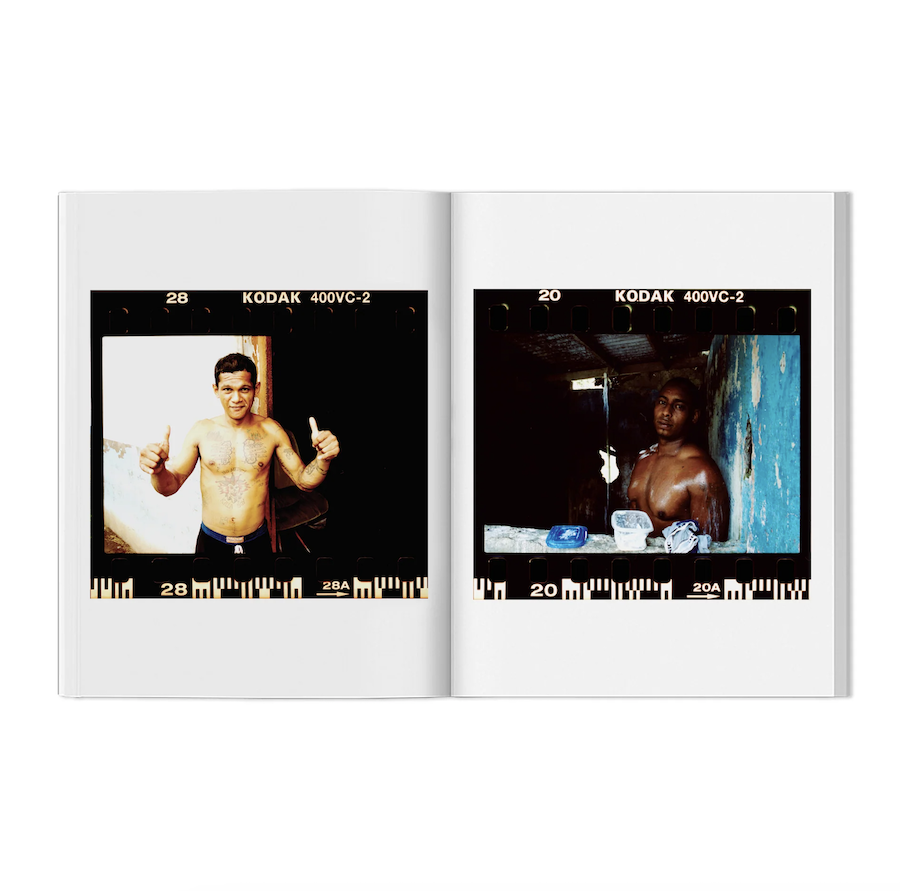

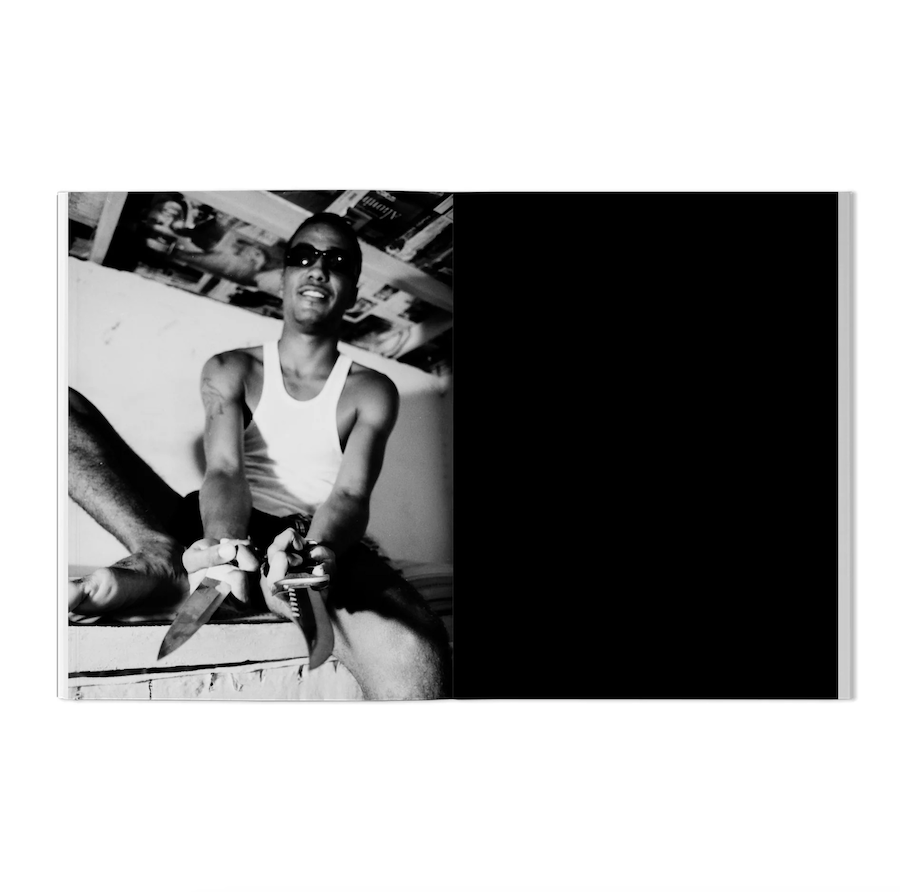

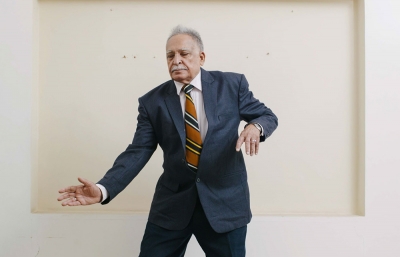

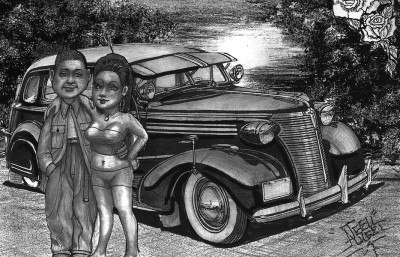

Estevan Oriol, long known as a renowned photographer who brings to light the unseen cultures around us, has captured the essence of life behind bars with his powerful and evocative Panama Prison series. The work sheds light on the harsh realities faced by inmates and offers a unique perspective on the human experience within these confines. What his camera finds is both captivating and disturbing. A quiet rawness, a subtle sense of pride, a hint of danger becomes the dominant visual narrative. These are the places we are often not allowed to go, that we have access to. Oriol goes there, opens up the prison walls without opinion or sentimentality: this work transcends the boundaries of conventional documentary photography.

“I was contacted to do a documentary on a guy that was in prison in Panama,” Oriol says of the origins of the project. “He had made a library in the prison with the help of his friend that lived in Canada, and this interested me. The friend would visit him and take a bunch of books each time until they had enough to make the library. The head of the prison liked what he did so much, he asked what else he would like to do, and the prisoner asked if could make a studio where the prisoners could record music. So by the time we got permission to go inside and take some photos and scout it out for the documentary, the guy he knew had got out of prison, but the music program was up and running.”

“We never did go back to finish the doc, so, these photos were all I had from the trip and that's how the story goes.”

But the photos have a volume, a powerful movement to themselves. They are contemplative and loud. That iconic Oriol aesthetic, the stark black-and-white tones add a layer of intensity to each image, emphasizing the starkness of the prison environment and the lives contained within. One striking aspect of Oriol's photography is his ability to humanize the subjects despite the dehumanizing conditions they face. Through intimate close-ups and candid shots, Oriol invites the viewer to connect with the inmates on a personal level, fostering empathy for those who are often marginalized or forgotten. There isn’t despair here, but a sense of power and pride, an ownership of individuality. In this sense, these photos give a social commentary on the broader issues surrounding incarceration, justice, and inequality. By exposing the harsh realities of life within these institutions, he prompts viewers to question the societal factors that lead individuals to incarceration and the effectiveness of punitive measures in fostering rehabilitation.

But more importantly, Oriol’s work becomes the antithesis of the glory that Keats bestowed upon Panama some centuries ago and what the potential of a canal to connect the world could offer. The hope of a new world and the ingenuity of man’s conquest of earth was what Panama should have represented, that when we open ourselves to the potential of exploration and innovation we would give more opportunities for people to thrive. And yet, Panama Prison is the striking reality of progress, that we shut away and close the door on many so that the system of law and order can serve the very few. Through his masterful use of access, Oriol gives the viewer a chance to examine the complexities of the prison system, how many men we shut away from society. Maybe these works will advocate for a more compassionate and equitable approach to criminal justice, or serve as a reminder of the complexity of humanity in the most trying of circumstances. Camaraderie born in chaos, vital life happening behind closed doors.

“All my portraits try to capture some part of the person's story, all in that one photo. A sense of life. And in that, I think it causes some type of emotion in the person looking at them.”

Text by Evan Pricco

Estevan Oriol Panama Prison Book is published by and available with BEYOND THE STREETS