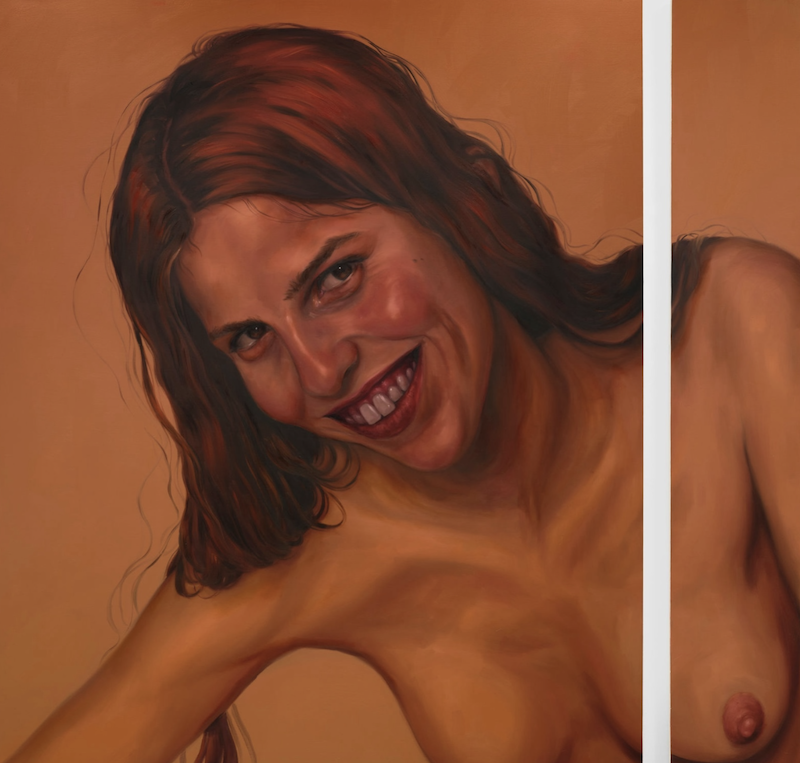

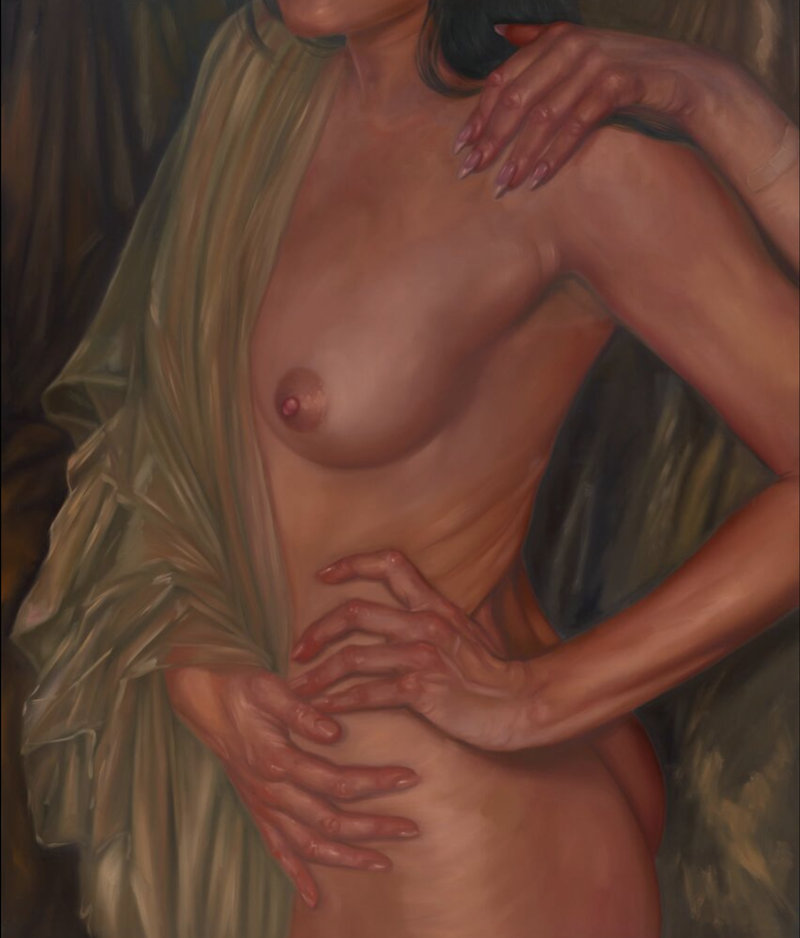

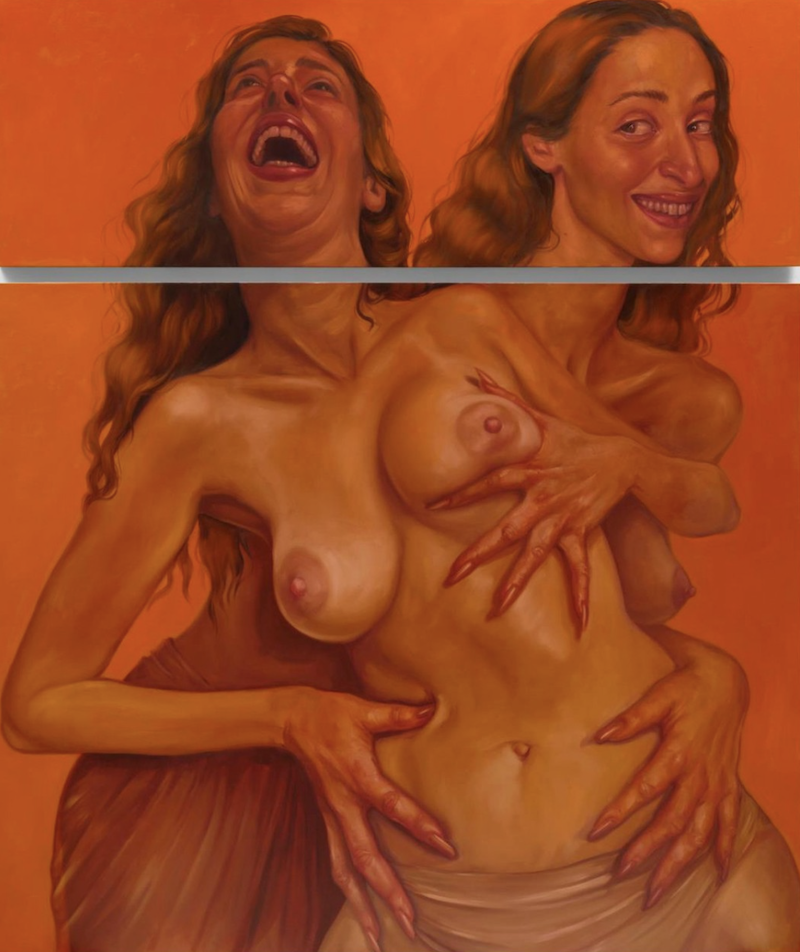

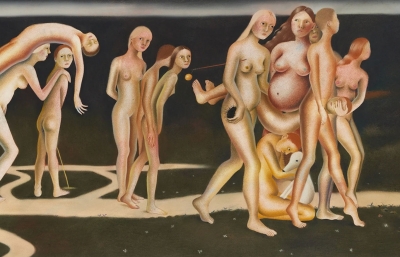

Almine Rech Brussels is pleased to present Torn Clean, Chloe Wise's fourth solo exhibition with the gallery, on view from April 24 to May 25, 2024. An ecstatic mouth, an elated smile, a tear-filled eye, a Baudelairean mane of hair, the sudden appearance of a breast, movements that seem to graze or caress the flesh—piece by piece, Chloe Wise makes bodies appear, coming to greet us, embrace us, then engulf us. We would like to be able to read their faces, and get to know them effortlessly, to easily categorize and digest their emotions at first glance. In response, the figures hold their poses, performing to perfection. We feel as if we are discovering a big, blended family, the artist’s clan of liberated figures, a band of sisters.

As we let our guard down, new details emerge. Everything seems too perfect, too smooth. A smile becomes a grimace. Tears of joy become tears of sadness. Through the artificially-sustained laughter and the superficially-relaxed poses, the painter quietly introduces an uncanny feeling, a disturbing current. At first it is minimal. Then, like a drop of perspiration running down an anxious spine, it triggers a sense of uneasiness in us. Despite the stillness of the figures, great dramas flash across the canvas. Like the calm before the storm, we see bodies suspended in the tense moment before extreme emotionality.

After welcoming us into her flawless world, Chloe Wise gradually introduces a latent, crushing fear. Even the dominant colors, lacking pigmentation and blurred with a suspiciously bright sheen, seem to warn us that danger awaits, lurking within us, in our own acceptance of a world that smooths out its surface to make itself presentable, and therefore bearable. Chaos is not far away—it waits, lurking in the shadows just out of eyesight. We think of Alfred Jarry’s phrase: “The more I touch a circle, the more vicious it becomes.” With an unrelenting passion, Chloe Wise forces us to reveal ourselves. Innocence is deranged.

The artist discusses the “flesh” color of Band-Aids, designed to stick on the skin to both protect the wound, and to make it disappear from sight. “Until now, Band-Aids have had their own generic yet distinctive color – that of the ‘Caucasian skin tone’, a sickly beige that mimics the skin of some without attempting to convincingly be skin…Band-Aids are imposters, fake skin meant to take on the role of the scab – the scab’s scab.” Images, according to her, can create the same artificiality as ‘skin-toned’ bandages: masking, covering the unbearable through imitation. By gradually subverting her “perfect” paintings, Chloe Wise challenges our way of seeing. Every painting becomes the bearer of multiple meanings and profound emotions.

Georges de la Tour needed candlelight to reveal the secrets of chiaroscuro, the intimacy of an existence stolen by darkness. Chloe Wise prefers a neutral glow, seemingly without harshness, one which gradually reveals the falsehood and filters that we impose on our own vision, deceiving ourselves. Tearing away these artificial alterations, tearing off the Band-Aids of our preconceptions. She questions, right where it hurts: the scope of the sacred, bodily act, and the world around us, whose calls to order we are constantly trying to escape. As the poet René Char wrote: “Lucidity is the wound closest to the sun.” It is the painter’s duty to reveal the hidden side of images. And in a world of endless imagery, a painter must offer her most intimate and secret visions. This is how Chloe Wise teaches us to see anew.— Boris Bergmann