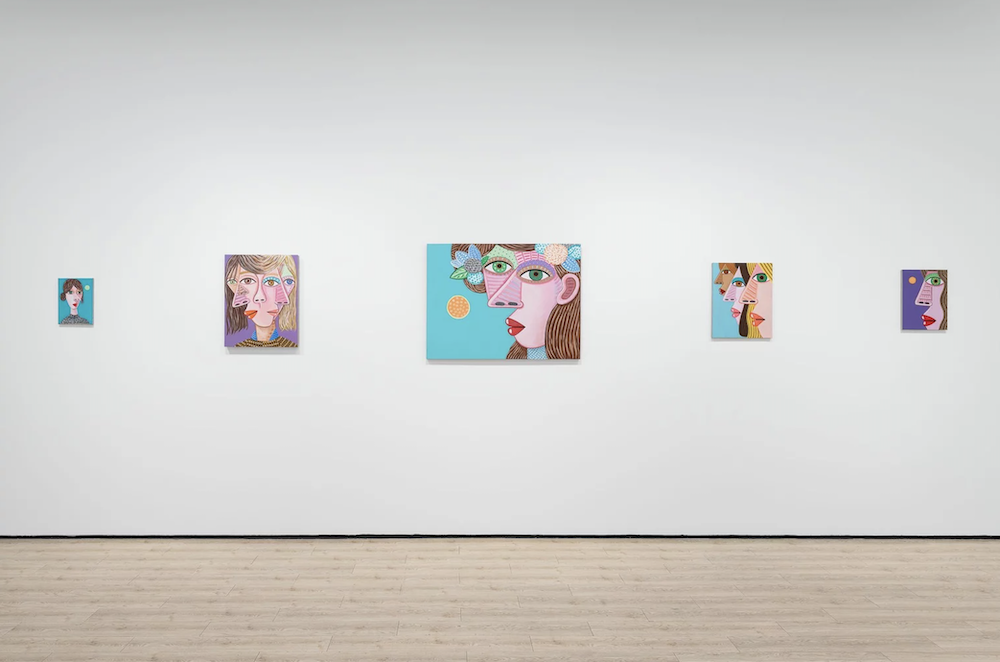

Almine Rech Shanghai is pleased to announce Crosstalk, Brian Calvin's eighth solo exhibition with the gallery, on view through December 2, 2023.

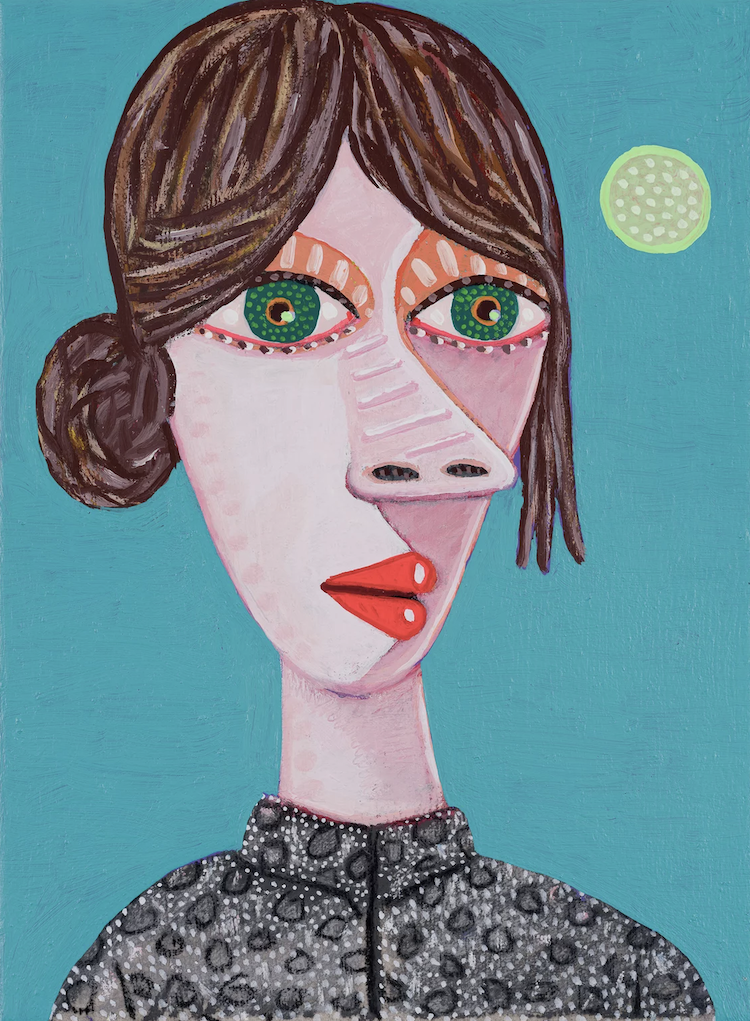

There are flatly colorful shapes, arranged just so and glossed with a highlight here and there, and we call it a girl—or many girls. She appears at different stages of life. She is becoming a woman, growing and maturing, changing before our eyes. In one painting, the parts of her face turn and point in different directions. Brian Calvin’s figures are in some kind of flux, oscillating between profile and frontal views, breaking open flat like a dismantled box. Small areas of dazzling dots and dashes encode the twinkle of an inner life, maybe a sadness, a moment of activity contained within herself and sheltered behind the sturdy graphic wall of composition. As we absorb her, face to face, she also slips away, temporarily elsewhere, in a touch-and-go relation with concreteness of form, line, and hue. I suppose change, growth, and evolution are perennial features of being, but in this pictureverse, such dynamics are hyperbolized and brought into focus by the fact that his subjects look to be in their second, third, or fourth decades of life. Often her features are stretched or swollen, with some of the soft, transitional awkwardness of adolescence. She is very wide-eyed. He’s interested in a perpetual coming of age. While his depiction of this figure of femininity extends back to his early works and predates fatherhood, the profound and consuming experience of parenting two daughters from infancy to, now, young adulthood has run parallel to his painting life in the studio, playing off the many pictures of fading girlhood like scenes from home flashing in close up. But Calvin’s girls and women are not specific people or even characters. They are not rightly portraits, they are both more and less than that. When paint coheres into recognizability at the same time that it bottoms out in flat color and pattern, there is a vital instability that builds the longer you look.

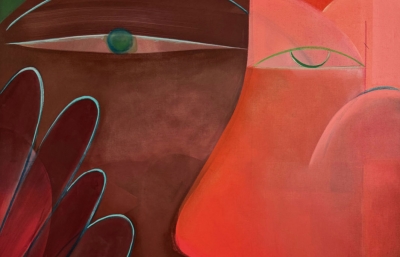

Over and over again, he paints the features of a face. Sometimes many times on one canvas and on one body. Because life is people and in the space of a human face there is infinite variation. The faces are so big, so vast, varied with flat and decorated expanses. They are made for falling into and floating on. There’s room in there, in each of them, even when crowded together up close, to see other things and find hidden worlds. Deep horizons and vortices, whole landscapes and high-rises with windows reside inside eyeballs, parted mouths, sheets of hair, and the side of a nose. She is monumental, containing and producing multitudes. Perhaps within the simplicity of her masklike features, she stands for the humanity of hundreds and thousands and millions of people. Repetition allows for play and recombination. The face—in certain prescribed views and mannered stylizations—is Calvin’s chosen structure within which he wants to dwell. It’s his way into paint, responding to the logic, wants, and needs of form and color. Often a visual stutter leads to two eyeballs being stacked one above the other, or lining up side-by-side and nearly touching end-to-end—the effect is mesmerization spiked by a jolt, an eye-rubbing double-take. The paintings, especially the many-headed stacked ones, are, in their way, a figurative take on abstraction, which is fitting because these specters of people do a good job portraying each person’s ultimate unknowability, opacity, and abstractness. The face is an excuse to make a painting, and that’s what he most wants to be doing, making a painting. And yet, a face is not just any arbitrary subject matter, it is, in fact, the most primary arrangement of shapes that we as humans are hardwired to make sense of and be engaged by from the start of our tiny lives. It is that thing we will never get over and that thing he cannot stop painting. Because life is people. — Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, art writer and curator