We are excited to share a preview today of Eric Croes' new exhibition, Monkey Puzzle, opening at Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica. Croes’ columns are to contemporary sculpture what a gourmet feast is to drive-through fast-food: More refined and customized and unique, they are also more demanding and satisfying and inspiring. Impossible to consume quickly, all repay, in spades, every bit of the attentiveness you bring to them, again and again and again.

At a time when art is trafficked in quickly, both online and in person, these handmade totems can be seen as old-school throwbacks: manually crafted objects whose physicality takes up space and time as they take us back to a world of face-to-face interactions, before so much of our lives were lived onscreen, at a distance from the real thing, in the anonymity of our handheld devices—heads bowed down, eyes focused 18-inches in front of our noses, brains in the ether, minds lost to what’s happening around us, IRL a distant horizon.

In contrast, the Brussels-based artist’s sculptures make you want to move around them—first to see if the sides and backs are different from the fronts, and then to ensure that your memory of what you saw first is accurate. While circumnavigating a sculpture, you also get drawn up close, so that you can savor every detail, which the artist has served up in abundance, and with more generosity than we are used to experiencing—in contemporary art, and in public life, which is anything but civil. At the same time, you’ll feel the need to stand back and take in an overall view of the whole sculpture, especially if it’s among the ones that tower overhead—and invite you to gaze skyward, toward the heavens above.

Even better is the opportunity to see a slew of these stacked ceramic heads, vessels, and other recognizable items—to stand, amidst pillars that support nothing but their own playfulness. It is as if you have entered a phantasmagorical forest, where you are free to meander every which way, setting off, on your own path, between and among the tree-like sculptures. That experience is nothing like staring at a screen in the palm of your hand. It’s 3-D. It’s sustained. It’s live. It’s participatory. And it draws the imagination into action. No two visitors interact with a roomful of these gregarious columns the same way. And no single visitor engages any one—or any installation—the same way twice. The experience is fleeting. It’s here and gone. Like every moment. And, eventually, like every one of us.

But before that happens, there’s plenty to enjoy at Richard Heller Gallery, where Croes has installed his third solo show in Los Angeles. Titled “Monkey Puzzle,” it refers to one of the most distinctive evergreens on the planet. The Araucaria Araucana is a hearty conifer with horizontal branches that grow in whorls and are covered, completely, with triangular leaves or needles, like the hide of an armadillo or the armor of an ankylosaurus. In terms of numbers, the monkey puzzle tree splits the difference between armadillos and ankylosauruses: neither as numerous as the former nor extinct, like the latter, it is an endangered species endemic to Southern Chile and Western Argentina. Similar species grew all over the globe before humans entered the picture, so the monkey puzzle tree is often referred to as an animate fossil.

That’s a pretty nifty description of Croes’ multipart sculptures. Ceramics, after all, have been fired in kilns—subjected to such extreme heat that they have been, in a sense, fossilized, like prehistoric bones and shells and plants. And, although these sculptures stand still, like unflappable guardians or implacable talismans, they are as lively as any animated cartoon, their eyes, mouths, and faces as expressive and engaging and filled with vitality as any human’s. Like movie stills or stop-action photographs, each feels as if it is part of an ongoing narrative, one we viewers stumbled into the middle of, and which implies so many previous and subsequent moments—so much backstory and so many future developments—that we can’t help but feel that there’s more to the story than immediately meets the eye, much of which we can discover if we simply pay attention.

What’s more, these towers of ceramic artifacts are structured like monkey puzzle trees: Except for the topmost and bottommost components, each component is sandwiched between two others. The vast majority of the items and creatures and beings that make up his multipart stacks do double duty as stand-alone sculptures and stand-atop-me pedestals, simultaneously drawing your attention to it, and it alone—while it functions as the star of its own show—and serving as the base or support or structural underpinning for another, as if singing back-up vocals, as it were, and so on and so forth, up and down the curiously composed column. That’s how it is with monkey puzzle trees: All that’s visible are the leaves or needles—no branches or trunks. From base to tip, every inch of a monkey puzzle tree resembles every other inch. A model of efficiency, every square inch of the tree’s surface absorbs sunlight for photosynthesis. Upon seeing an Araucaria Araucana specimen in his colleague’s garden in Cornwall, England in the 1850s, a Victorian barrister remarked “It would puzzle a monkey to climb that.” The name stuck.

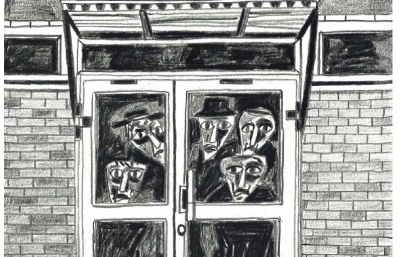

And imaginative puzzling is exactly what Croes is up to in his art. It’s what he does in the studio, when he’s sculpting the objects and icons and visages and figures and critters and personages that eventually commingle and cohabitate to form his funky, columnar, Brancusi-might-be-a-distant-relative sculptures. It’s what he does outside the studio, when he picks up his sketchbook and sets to drawing and doodling various versions of the figures and things that find their way into his works, whether they spring from his dreams—both waking and from the depths of REM slumber—or from his memories of everything he has ever seen, in a museum, a gallery, or a kunsthalle; in a book, a movie, or a catalog; in print, online, or in his mind’s eye. It’s also what his sculptures do to us: set us off on unscripted, improvised, and multi-directional journeys—scrolling through our own memory banks and recollections and reveries and fantasies and free-associations and half-baked thoughts to provide the narrative glue that might hold together his various menageries of evocative elements—so that each sculpture’s odd cast of characters and strange amalgamation of props form some kind of more or less coherent story, which makes some kind of more or less sensible sense.

Those narratives need not be limited to the rigors of rationality, nor be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. They are poetic, not logical; metaphoric, not literal. That’s because they are propositional. More focused on generating possibilities than wrapping things up, tying things down, or eliminating loose ends, these narratively promiscuous sculptures are all about stimulating ideas, starting conversations, seeing possible links between and among different times and far-flung places. Most important, they build upon those connections and echoes and confluences to form bridges between and among different histories and distinct peoples. All in all, these works are on the lookout not for similarities between and among all of us. Their goal is to find and forge unexpected connections across time and space, to concoct and cultivate bonds not based on identity or resemblance, which is kind of narcissistic, but on the capacity to reach beyond what you are familiar with, and possibly become someone—or something—other than whoever—or whatever—you were when you began looking at these horizon-expanding totems.

That’s why Croes’ sculptures traffic in vague resemblances. Maybe and kinda and sorta—rather than exactly, precisely, and certainly—are the operative terms at work when looking at any—and all—of his enigmatic yet oddly familiar figures, each stacked neatly atop—and below—one another. A quick glance around the two galleries in which “Monkey Puzzle” has been installed calls to mind sculptures from ancient Egypt, others from ancient Greece, and still others from Rome. Pre-Columbian vessels, both ceremonial and utilitarian, from Central and South America, come to mind, along with carved wood figures from the Pacific Northwest and what is now Canada. The same goes for prehistoric sculptures, including Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic artifacts and icons, whose purposes are mysterious and whose impact is all the more potent for being unknown.

That’s what Croes is after in his art: the sense of mystery that inhabits objects we don’t fully understand or completely comprehend, the spark of life that enlivens us when we are alert to—and in touch with—its vitality. “Monkey Puzzle” is a stepping-stone toward a future that takes viewers of all shapes and stripes off the path on which we have been headed for the past twenty or thirty years, and toward something different—not the Garden of Eden, to be sure, but a world populated by animate fossils, where lots more than usual is possible because the past is present—and monkeying around is the best way to go.