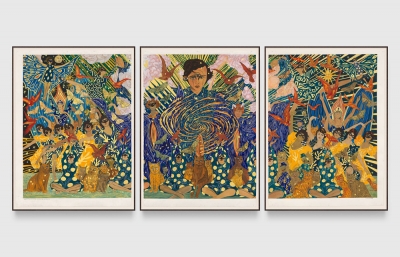

Debuting a new series of paintings at White Cube in Seoul, Tunji Adeniyi-Jones’s solo exhibition ‘Immersions’ explores the diasporic body, African subjecthood and autonomy. Born and educated in the UK and now based in New York, Adeniyi-Jones draws on his Yoruba heritage, the ancient history of West Africa and its mythology, as well as the Black American culture of his immediate surroundings. While his practice is grounded by these biographical details, Adeniyi-Jones uses painting to engage with what curator Ekow Eshun has referred to as ‘a broader, deeper sense of African possibility’. For his first exhibition in Korea, Adeniyi-Jones has created a new series of paintings that respond to the context of Seoul, and mark a new development in his exploration of the interplay between figure, environment and motion.

Citing painting’s ‘innate ability to capture form and physicality’, Adeniyi-Jones has established an artistic sensibility that places figuration in dialogue with the language of abstraction. His influences are wide-ranging, merging cultural signifiers to create spaces that are both fantastical and rooted in diasporic narratives and histories of exchange. For the artist, the human body serves as a vessel for storytelling, becoming a site for modes of self-governance, conveyed particularly through the elastic gestures of dance. His paintings are populated with highly stylised, genderless figures that seem to writhe, dip and dive across the canvas. They are rendered in free-flowing lines that are informed by Nigerian Yoruba practices of body painting and scarification, but with a ‘loosening of specificity’ so that they are free to move ‘across and between histories and spaces’. Abstraction, in turn, becomes a tool for representing ‘a different kind of Blackness’, a liminal space wherein the figure may exist as symbol, deity, mythical creature.

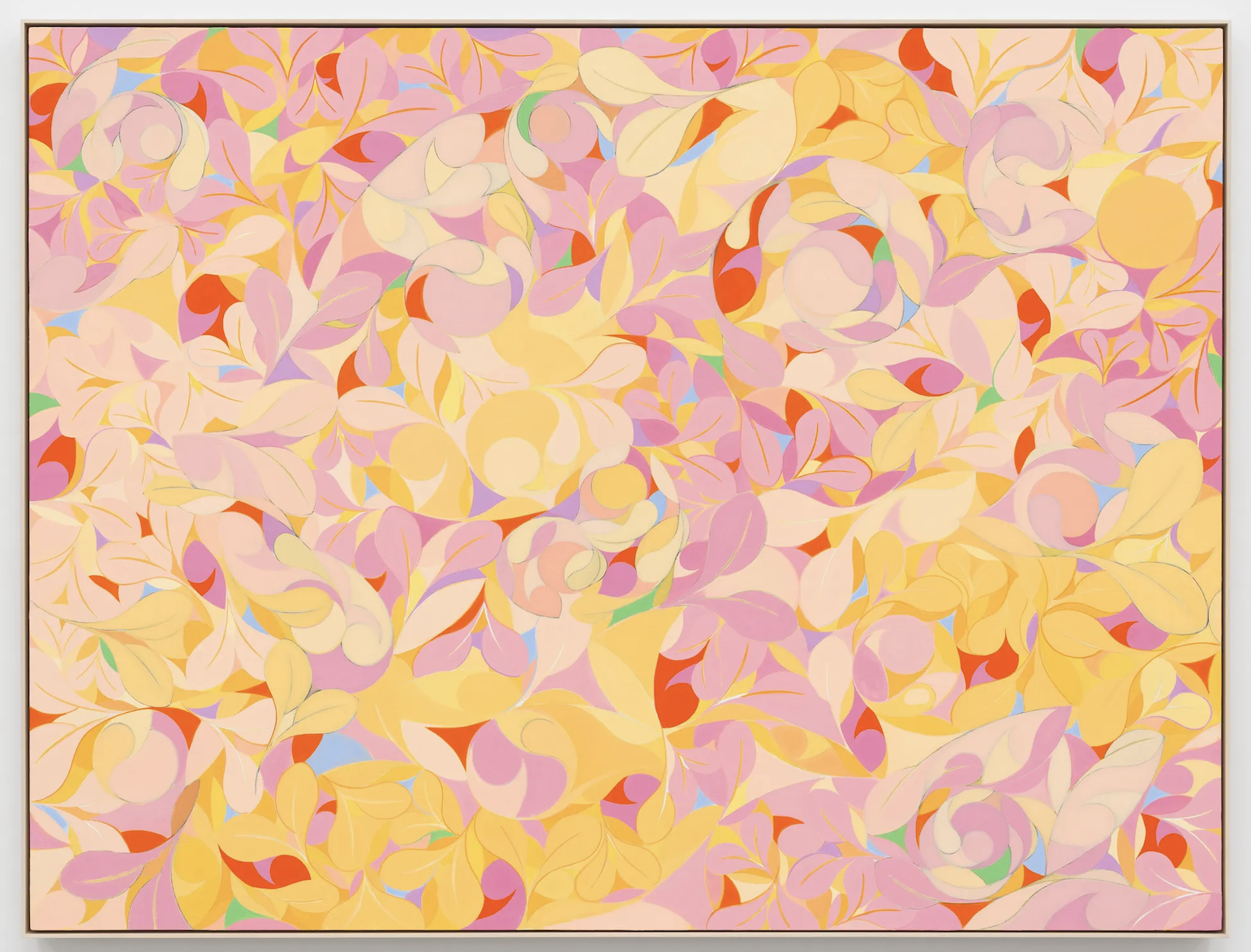

Adeniyi-Jones’s figures emerge from environments that simultaneously recall verdant undergrowth and the ornamentation of the Arts and Crafts movement. The sinuous, leaf-like forms that comprise these dense backgrounds complement the curves of the fragmented bodies, conjuring a sense of rhythm and motion. Adeniyi-Jones’s interest in dance also speaks to this notion, drawing parallels between the fluidity of movement and the plurality of selfhood – especially as a resistance to the projected desires imposed on Black bodies. Supported by the artist’s research into African dance practices during the transatlantic slave trade, Adeniyi-Jones examines how these traditions have been preserved and reimagined, and what role they continue to have in one’s sense of liberation and autonomy against the fixity of the ‘Othering’ gaze. Here, Adeniyi-Jones also makes reference to the work of African American artist Aaron Douglas (1899–1979), a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance who adopted the silhouette as an expression of multiplicity.

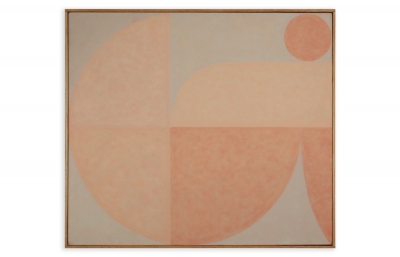

‘Immersions’ closely follows Adeniyi-Jones’s site-specific work Celestial Gathering (2024), which was included in ‘Nigeria Imaginary’, the country’s national pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale. Installed on the ceiling of the grand Palazzo Canal, Celestial Gathering represents a pivotal step in the artist’s exploration of spatial engagement between viewer and work. Produced shortly afterward, the paintings in ‘Immersions’ consider the relationship between the painted body and the space that envelops it, and see the artist developing his visual lexicon further still. Over the past five years, the subjects in Adeniyi-Jones’s paintings have addressed varying degrees of movement, from the performative gestures of dance to acrobatic dives, now culminating in what the artist terms ‘a spheric orbit motion’. This evolution comes in tandem with a challenging of the traditional gravitational anchors of painting, resulting in compositions without a fixed orientation or ‘true north’. Rotating the canvas while he works, the artist creates a space with an indeterminate horizon line, in which the relationship between foreground and background is destabilised.

In a notable departure from his previous works, here the artist shifts his focus to the surrounding space, such that in some paintings, the body is completely obscured. As he states: ‘I’m interested in depicting the reverberation and chromatic frequency that these bold characters leave behind’. Each painting begins with the figure as a compositional guide but through a meticulous process of layering, their forms gradually ‘dissolve into the picture plane’. In Blue Violet Tower (2024), for example, the curved forms that might have previously delineated a shoulder, spine or leg, instead represent a mere ripple in the fabric of the surrounding environment. As is typical of Adeniyi-Jones’s practice, the works in ‘Immersions’ employ distinct palettes: blue-violet, red and pearl white. The artist’s codification of colour can be traced back to his interest in the New York School, particularly the vast canvases of Lee Krasner (1908–84). In this series, the use of pearl white is informed by the prevalence of mist and fog in Seoul, as well as the significance of white as a symbol of the heavens and temperance in Korean culture.

In Adeniyi-Jones’s canvases, the almond-shaped eyes are the last element to be added, and their direct gaze punctuates his compositions. The bodies he paints are not passive: they take up, hold and move through space. They are looked at, but they also look out directly at the viewer. For the artist, this interchange speaks to W.E.B Du Bois’s conception of ‘double consciousness’ – of existing simultaneously in one’s sense of Black identity and the ‘Othering’ gaze of others. It is within this charged space – between autonomy and expectation – that Adeniyi-Jones’s abstracted figures celebrated the multifaceted nature of selfhood.