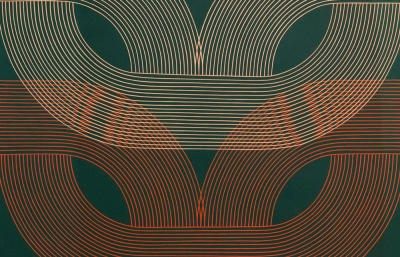

Richard Colman's work is known for blending figurative imagery and bold geometry. Typically constructing symmetrical compositions, he explores themes of human sexuality, societal hierarchies, life and death. Currently, Colman splits his time between San Francisco and rural Connecticut. The artist’s latest body of work was created in the latter at his farm-turned-large-scale-studio, where the generous amount of space, solitude, and slower pace of living provoked an introspective focus throughout the pieces’ creation, with compositions inspired by sensuous qualities of nature.

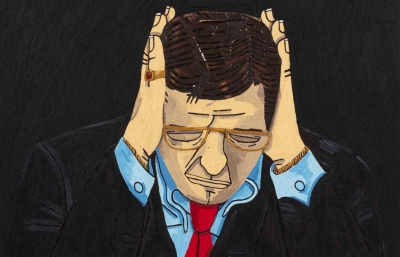

The paintings in Sometimes it’s a Flower, Sometimes it’s a Weed at Louis Buhl & Co. parade rigid, guarded figures that are secluded and closed in on themselves, as if trapped in a fortress constructed by their own body; each one is meticulously laid out in a way where it is isolated yet seamlessly interwoven into the composition. At first glance, the subjects are distinguishable. Upon closer examination, their seemingly boundless limbs gradually fuse into the work’s background, making for a complex visual narrative driven by a manifestation of color and texture. Colman intentionally neglects the explicit assignment of gender to his subjects, however, notes a subliminal draw towards the nuanced disposition of femininity.

Before Colman approaches his paintings, he prepares by creating stacks of drawings, sometimes hundreds, as initial guides. Rather than working to replicate the studies in his larger works, Colman views the drawings more so as agents in providing himself with the mental comfort and confidence to get the final products moving and uncover what is possible. As Colman explains, “one of the foundational aspects of the geometric figure paintings is the attempt at perfection, a goal almost impossible to reach. That, I think, is relevant to most of us as people, as we often want to give our best while being aware of our shortcomings and our imperfections. It is a very human quality, a quality I like these paintings to represent.” This statement attests to the artist’s process, where initial ideas shift and change throughout the paintings’ development as a result of his trust in intuition, allowing traces of the human hand to illuminate the canvas. More vastly realized is an overarching theme of balance: between measure and instinct; perfection and flaw; figuration and abstraction; chaos and peace—the concept is even materialized literally in the paintings, where bodiless heads rest upon the palms of the central figures. The act of harmoniously marrying opposing forces proves both a constructive principle of Colman’s work and an active element in its formation.