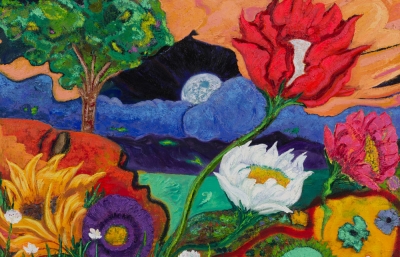

Jack Barrett presents Hammer, a solo exhibition of oil paintings by Philadelphia and West Virginia-based artist, Paul Rouphail. In his latest body of work, Rouphail masterfully interlaces the traditions of still-life and landscape painting, combining elements and techniques suggestive of a number of genres: the Hudson River School, American Regionalism, and European Surrealism.

Echoing Hermin Melville’s 1859 poem “The Portent,” Rouphail’s paintings conjure the image of John Brown, the American abolitionist famously tried for treason and hanged for the raid of the US armory at Harpers Ferry. In several works, Rouphail references Brown explicitly by inserting historical depictions of the abolitionist into his still-lifes, such as John Stueuart Curry’s 1939 painting titled John Brown, or Horrace Pippin’s 1942 painting John Brown Going to His Hanging. But as in Melville’s poem, Rouphail also evokes Brown through prosopopoeia––a literary device in which an abstract thing is personified––and likens him to a variety of objects set in scenes both real and fictitious.

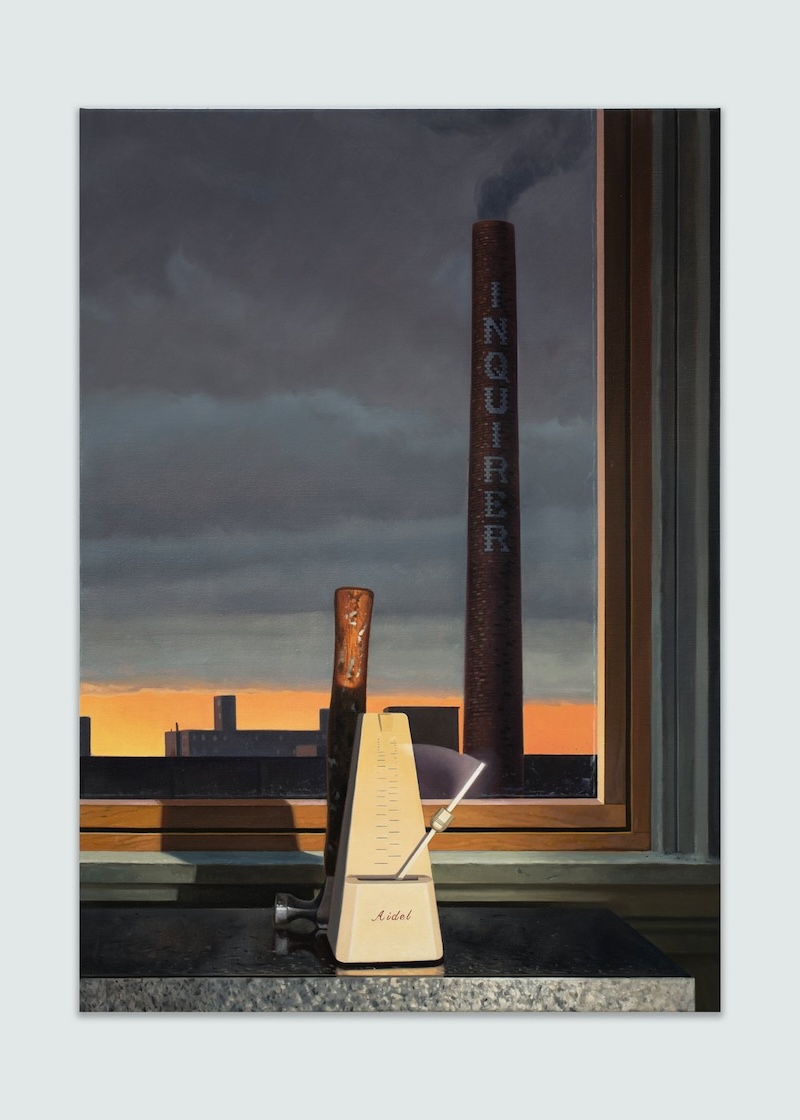

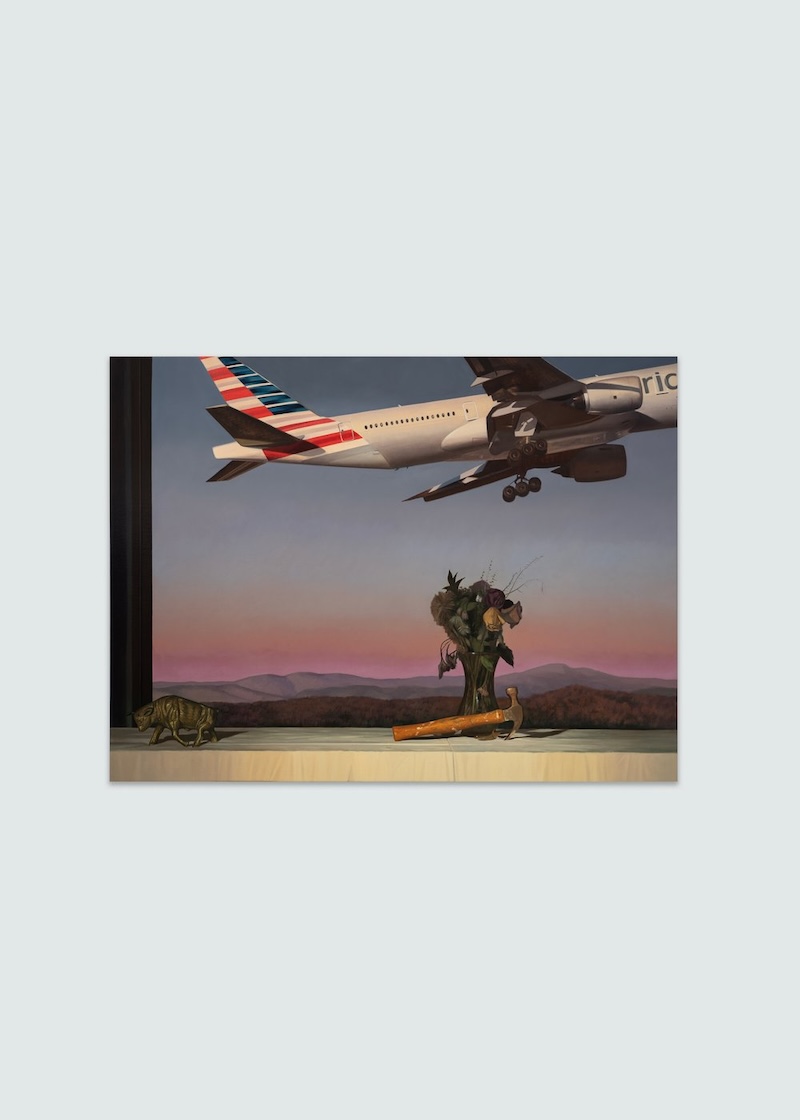

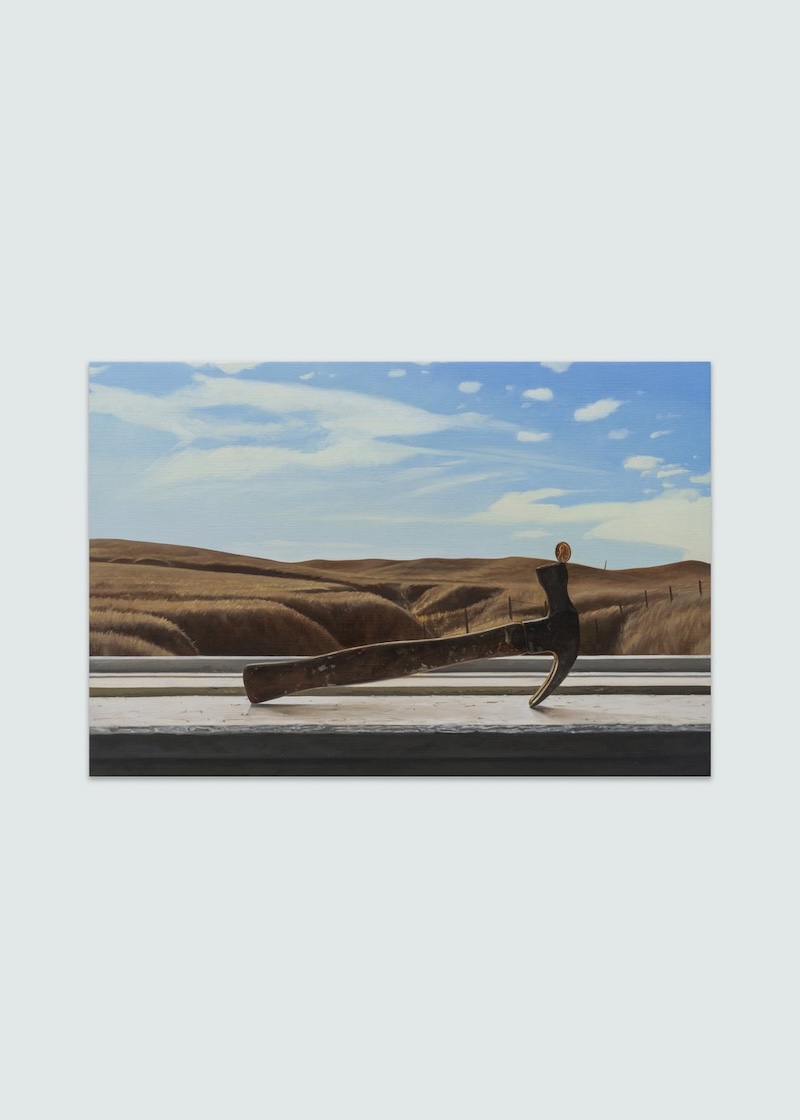

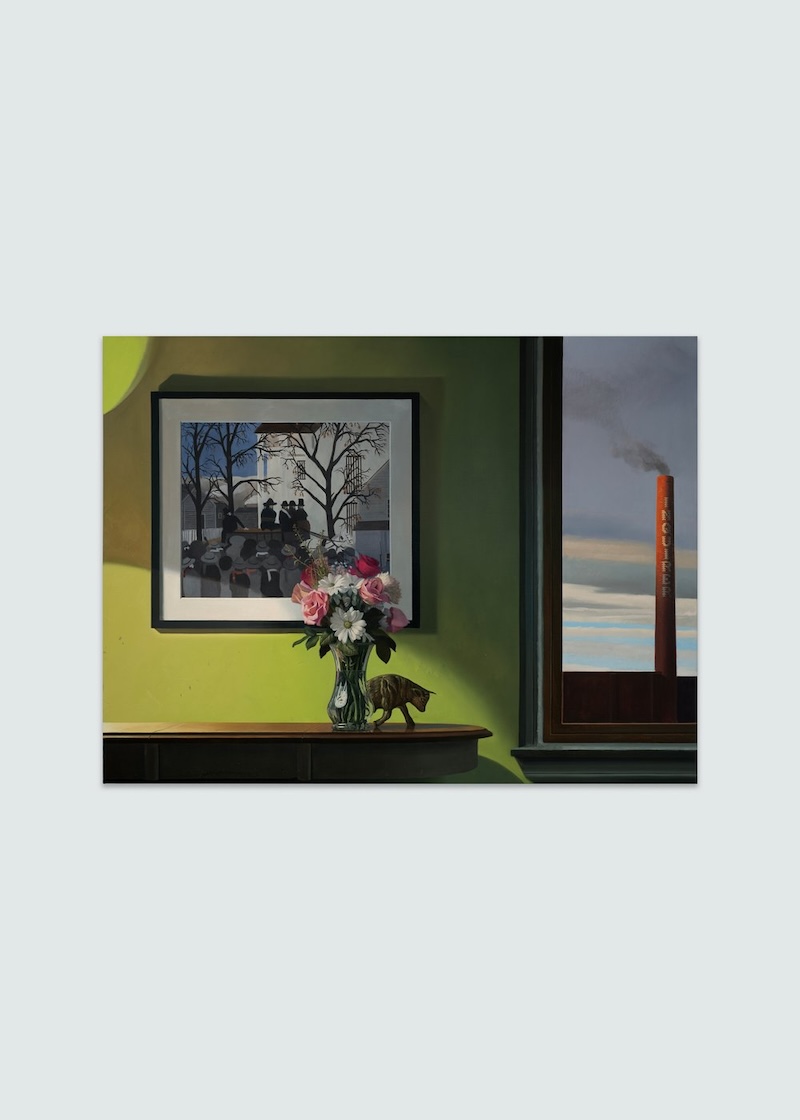

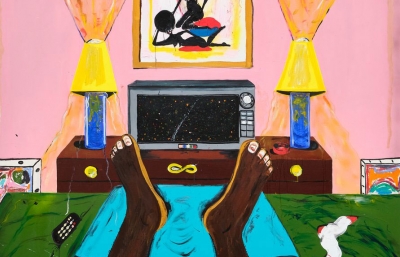

Virtually all of the works in Hammer depict varying combinations of five objects: a hammer, a miniature brass bull, a globe, a vase of flowers, and a smokestack painted with the text INQUIRER in white vertical lettering. These objects appear in divergent sets of interior scenes and landscapes that fold into each other, creating beguiling new associations and interpretations. In American Landscape and Pietà, two paintings that inventively reprise one of the most venerable tropes in Christian art, the pietà, the deceased Christ is suggested by a hammer, while his grieving mother is represented as a brass globe and a vase of flowers, respectively. The vase also appears in December Morning, where it sits like an offering before a framed recreation of Horrace Pippin’s painting of John Brown’s death. In Rhythm of the Setting Sun, a cream-colored metronome mimics the obelisk in Giorgio de Chirico’s l Sogno di Tobia, 1917, with text reading “Aidel” in reference to the Greek eidolon, meaning phantom or ghost.

Various landscapes and urban scenes from across the United States appear throughout the exhibition, as do such disparate objects as commercial aircrafts, which dwarf the other elements in the compositions. As in Melville’s poem, the effect is that the phantom of John Brown lingers, despite rarely being summoned explicitly. Thus, Rouphail’s paintings testify to the insistence with which the historical past finds its way inexorably into our contemporary moment, though its traces are not always direct or easy to see.