A Tension Worth Keeping Because the Drift is Always There presents a group of new paintings by Nathaniel Oliver that follows a cast of characters over the course of a day as they navigate a single landscape. Combining imagery from his travels; figures based on friends, loved ones, and, in this exhibition, his own likeness; objects from his research into the material culture of West Africa; and elements of fantasy, Oliver layers references from our world into paintings that work like speculative fictions. This mosaic of interrelated vignettes offers only glimpses into his characters’ narratives. By allowing us to imagine what happens in the space and time between the panels, the artist invites the viewer into his story of a community fighting for self-preservation in the face of danger lurking just outside the frame.

We Need Our Paranoia to Keep Us Safe (2025) draws on the dystopian science fiction of Octavia Butler: the painting’s central subject, a woman pouring a jerry can of water on a fire to make sure the group she is traveling with cannot be tracked, comes from Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower, which imagines the year 2025 in post-apocalyptic Los Angeles. The painting is an allegory for the negotiation between the harsh realities of what it takes to survive and comfort, represented by the figures shrouded in blankets. Depictions of textiles have consistently appeared in Oliver’s work as moments of abstraction as well as references to material histories; here, their geometric patterns allude to Oliver’s family’s long history of quilting.

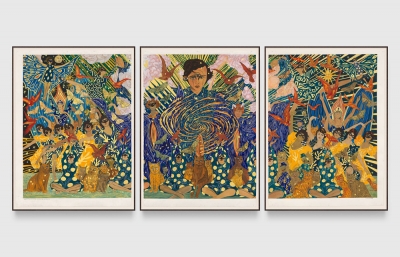

In The Break Off (2025), a group flees an unknown threat, their shadows projected by a fire onto a rock wall behind them like those in Plato’s cave. Figures move between canvases—Could It Be This Easy (2025) centers on the sibyl, a character whose presence here calls back to her appearance in Oliver’s previous paintings. Wearing a canary-yellow dress, she looks askance toward something beyond the bounds of the canvas, if lost in thought or the middle of a vision. A chorus looks down at her from a set of stairs: are these women judging the sibyl, who has spilled a glass of red wine on the perfectly kept lawn, or are they in awe of her composure? Throughout, Oliver plays with levels of realism, rendering some passages in flat color—the pink balloons, the yellow dress—and others in painstaking detail.

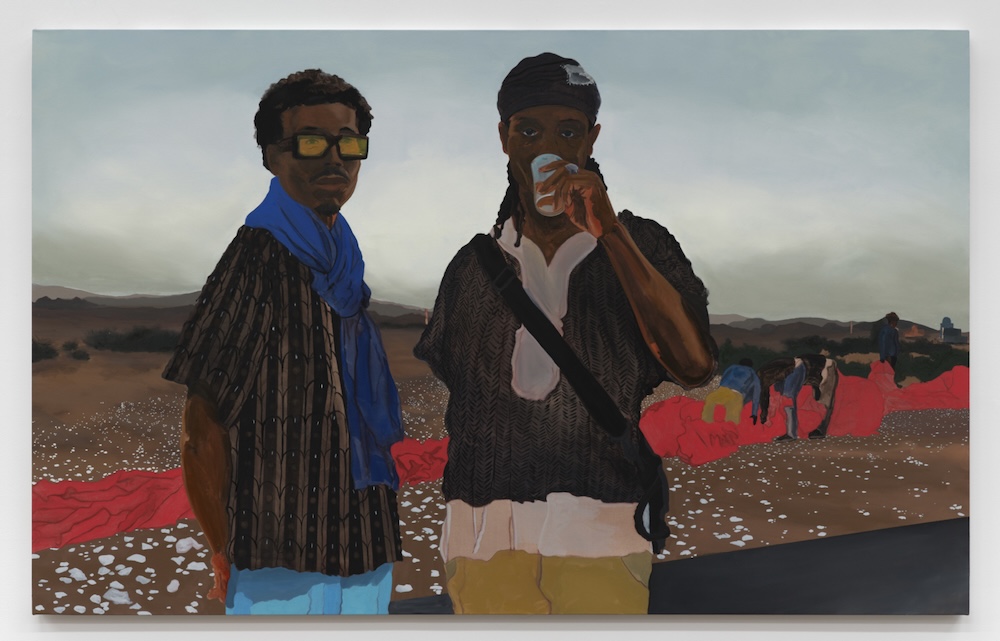

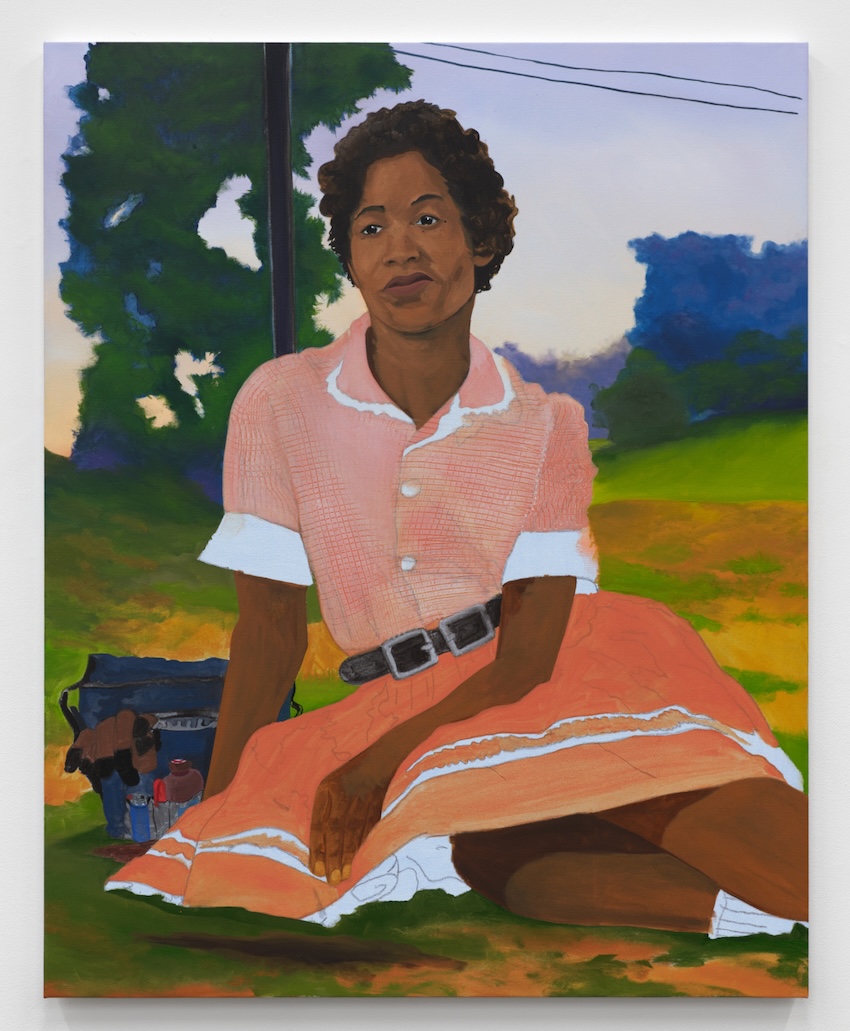

Many of Oliver’s recent compositions are at once portrait and landscape, deep spaces where wilderness is the setting for characterological studies occurring on the plane closest to the viewer. The horizon is omnipresent, most prominently in It Will Take Some Planning (2025), which juxtaposes a mountainous sprawl that recedes into the distance with two figures who seem to stand directly in front of the viewer. The work is a double portrait of the artist in two different guises—Oliver in conversation with alternate versions of himself. The woman at the center of Something on the Horizon (2025) is drawn from an old photograph of his grandmother. The saturated foliage and periwinkle sky behind her makes evident the influence of the abstract landscapes of Richard Mayhew, whose imaginary vistas challenge the historical genre’s claim to objectivity. Bountiful Blue (2025) shows this world once Oliver’s characters have left the frame: even without actors, the landscape tells its own story.