In the Juxtapoz Fall 2024 Quarterly, Charles Moore wrote in his survey on contemporary Mexican art, "Based in New York, the Columbia University professor Aliza Nisenbaum paints colorful portraits that humanize underserved global communities, offering an intimate look at diverse cultures and relationships. Through an often political lens, Nisenbaum gravitates toward the popular aesthetics of Mexico, such as the intricate textures, patterns, and bright colors of her upbringing. No identity is homogeneous, she notes, and this viewpoint is apparent in the artist’s paintings. Nisenbaum’s works showcase the plurality of humanity, our traditions, and micro-differences, with an emphasis on solidarity, sensitivity, and access."

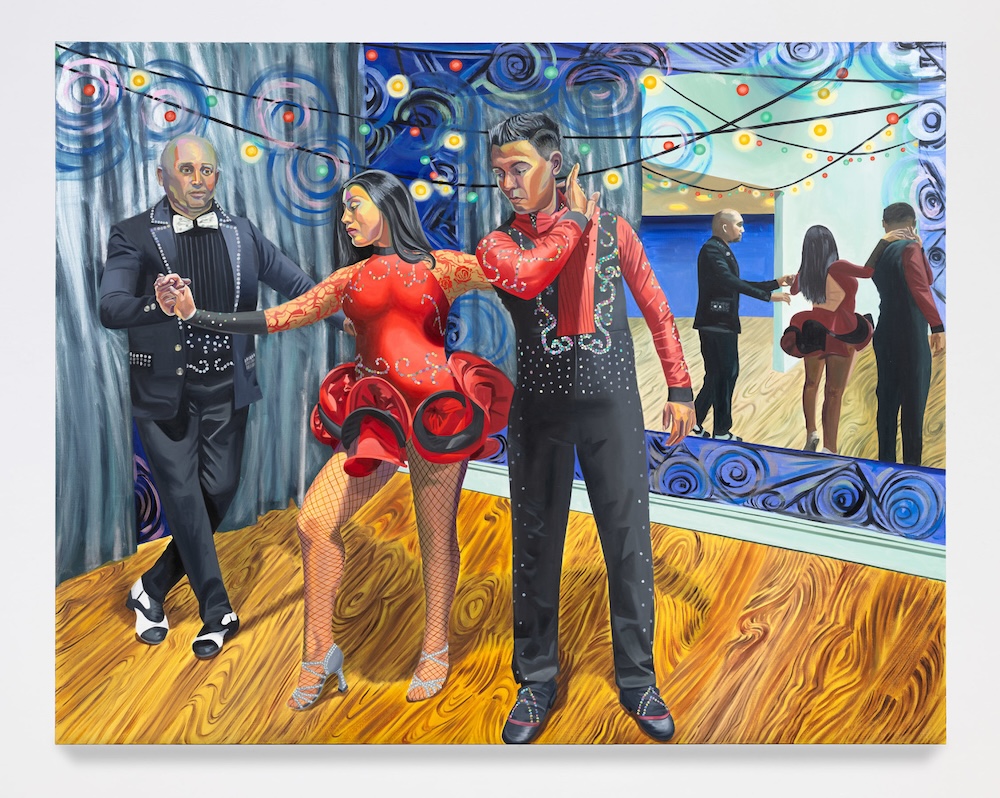

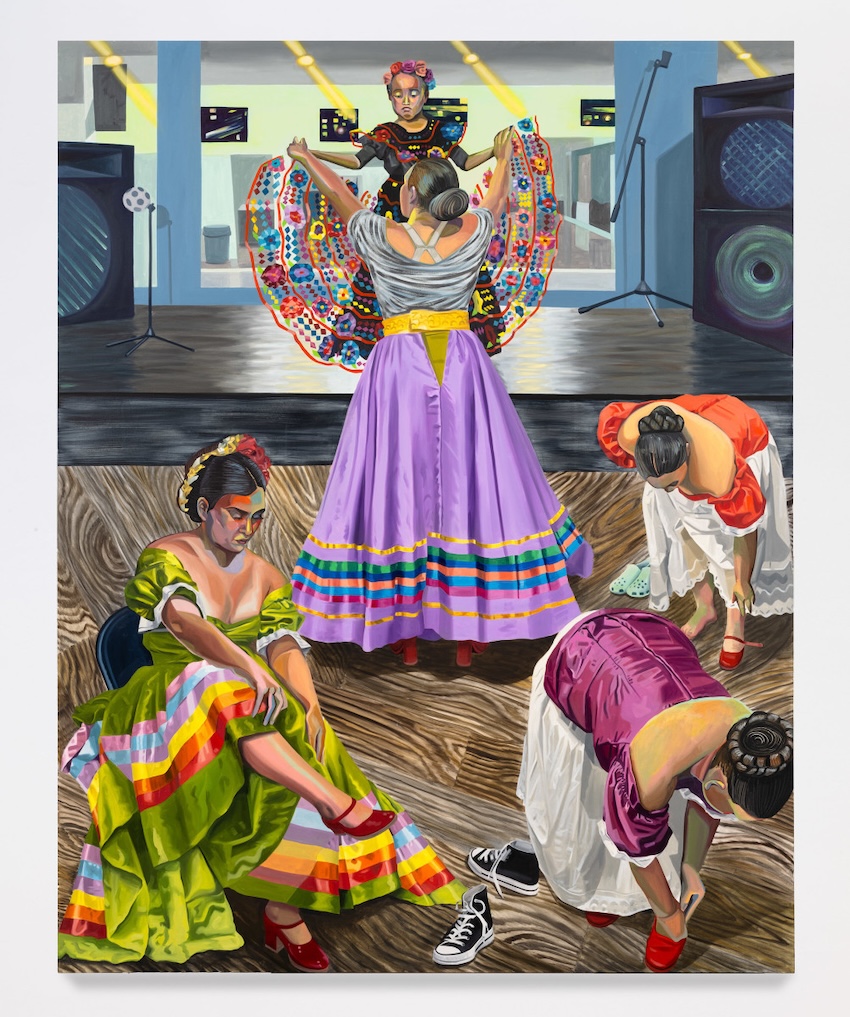

Regen Projects is pleased to present Altanera, Preciosa y Orgullosa, New York-based artist Aliza Nisenbaum’s first exhibition with the gallery and in Los Angeles. The exhibition will feature a new body of work depicting dance troupes, studios, and teachers local to Southern California, including Teresita de Jesús of Studio 10, Folklorico Revolución, Mariachi Tierra Mia, and Amelia Muñoz Dancers. Informed by her origins in Mexico and prior work with immigrant and diasporic communities, Nisenbaum’s lively compositions exemplify the artist’s dedication to fostering connection and community in the space of painting.

An early, leading figure in the centrality of representation and portraiture in the preceding decade, Nisenbaum develops vibrant, figurative paintings through a form of participatory observation. She forges relationships with her subjects and connects meaningfully to the complex communities they create together. Informed by a diverse array of artistic and political traditions, Nisenbaum’s pictures (and the process through which they are made) recall forebears such as Alice Neel, Sylvia Sleigh, and Diego Rivera.

From mariachi to salsa, the works give painterly shape to the fleeting festivity of these traditions. Exploring connections between sight and sound, they evoke music and movement in an otherwise static, silent medium by way of color, contour, and pattern. As such, they recall modernist experiments and visionaries such as Sonia Delaunay and Florine Stettheimer. Mindful of the ever-intensifying specter of technology that shapes our daily lives and recalling sociologist Émile Durkheim’s theory of “collective effervescence,” Nisenbaum’s paintings celebrate these spaces and occasions for dancing as consecrated moments apart from our screens and devices, reminding us of the pleasure of being more fully of and with our bodies and each other.

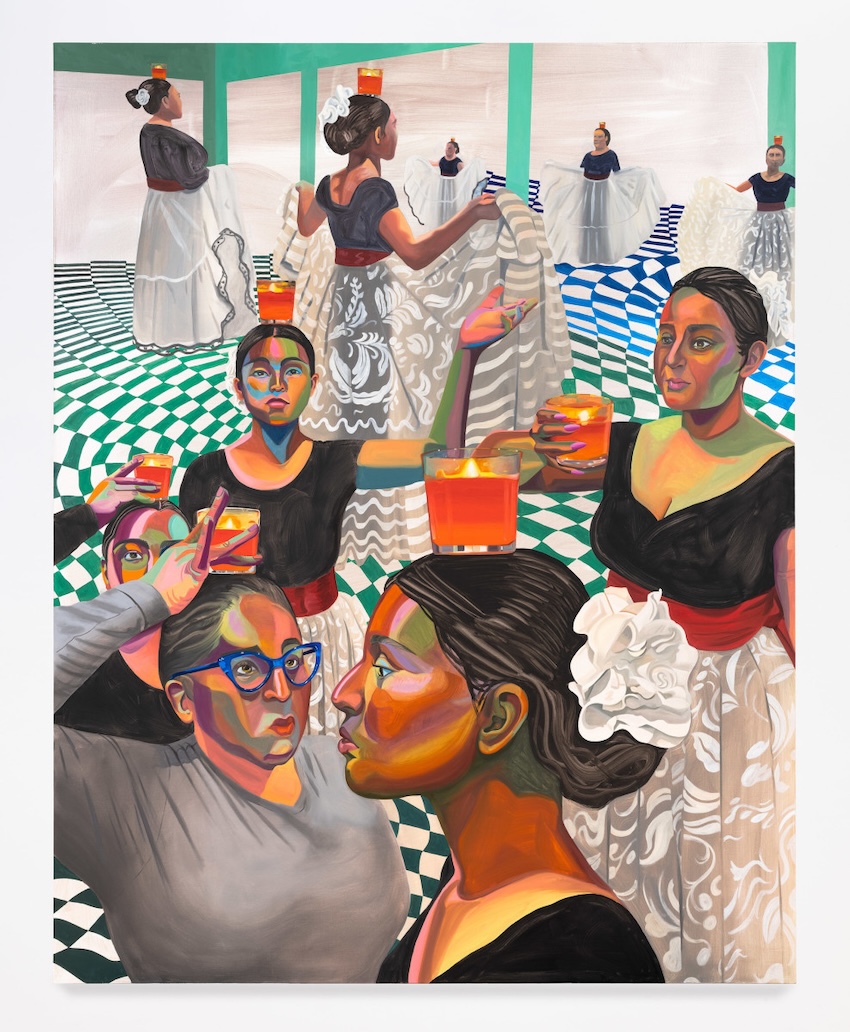

The exhibition’s title, Altanera, Preciosa y Orgullosa, draws from “La Bikina,” an iconic Mexican ballad, and describes the song’s namesake subject, a “haughty, gorgeous and proud” woman. As such, it alludes to the sounds and sentiments that might accompany the dancers and musicians pictured throughout Nisenbaum’s paintings, as well as her overarching interest in depictions of female power, independence, and self-assuredness. These themes recur in La Bruja, a painting of dancers learning to carry lit candles safely atop their heads as they dance to lyrics that describe a witch, or “bruja,” at work in the middle of the night. For Nisenbaum, La Bruja, like “La Bikina,” evokes a powerful mythology of strong women, informed by their own agency and control as they move through the world.

Poised and focused, Shine Arm Styling, on 1, introduces us to a duo especially attentive to the most decisive details. Likewise, Nisenbaum’s paintings orchestrate a carefully calibrated concert of humming patterns and colors, from the rhyming latticework of tights to the gauzy curtains that drape and cocoon the rooms, the lacey fretwork of leotards and costumes, and the pronounced grain of the wooden floors. Animating and unbridled patterning recurs across the canvases, a painterly translation of the energy of the dancers and the spirit of their music. Just as the women tap more and more frenetically in La Bruja—building and accelerating—the pattern that frames them expands through and beyond the figures, likening the sonic experience to this visual effect, as well as the pace of paint handling that produces it.

Similarly, as dancers slide and screech to a halt, the undulating motion of the wooden floors mirrors the movement of the figures via painterly gesture. Rehearsal mirrors and elevated bars occasion playful angles, geometries, and juxtapositions, expanding and suturing spaces and passages. They punctuate, frame, divide, and at times provocatively double or even triple figures and forms, creating and implying pictures within pictures. Such reflections liken Nisenbaum’s activity as a painter to that of the whirling dancers. Her complex tableaux reveal her deep awareness and clear delight in the possibilities of painting to narrate human experience and the relationships that sustain us.