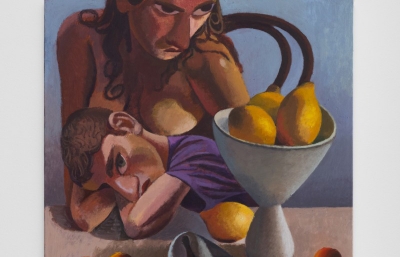

Peter Uka

ABC to XYZ

Interview and portrait by Sasha Bogojev

Coming from a culture where history is interpreted and passed on through an oral tradition, Peter Uka has decided to channel his talent by painting pictures that tell those stories in insightful, affectionate social chronicles. With classical training in realistic figuration, the images flow straight from memory onto the canvas, sometimes highlighting and necessarily glossing over idiosyncratic imperfections, his deft methods breathing life into dynamic portrayals.

Scenes witnessed while growing up in Nigeria, the bright, surrounding colors and patterns, as well as behaviors, mannerisms and local customs are all captured in vibrant, visual narrative. Driven by the imperative to introduce his homeland and culture to the rest of the world, Uka’s work also provides a personal, emotional link to the life he left behind after moving to Germany back in 2007 to study at Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. The mixture of oversaturated, tropical colors, exaggerated contrasts, and the graphic, journalistic feel of the scenes depicts a view of recent history that has been missing in the global narrative. Luckily, Peter Uka is determined to recreate those moments on canvas and tell those stories with brush and oil paint to anyone willing to “listen.”

Sasha Bogojev: I want to start with your introduction to art. How did that come about?

Peter Uka: It was more like a marathon, as I grew up around it. My father is a self-taught artist, and he ran his workshop in the little town in Benue State in Nigeria. And my father used to, well, he still does, have a lot of apprentices. He teaches sign writing, drawing and stuff like that. Back in those days, we didn't have printers and stuff, so he was doing all the sign writing for businesses. He made those, and I just grew up around it.

And at which point did you expand to an interest in fine art?

I was always in love with it, I always wanted to do it. But my father, like most African parents, didn't want that. They feel like you have to study to become a doctor or an engineer and stuff. They always want something which they think is better than what they have.

So I started first tapering towards architecture. But, along the line, I dropped that, and then I just went fully into art. So I started in Nigeria, at Yaba College of Technology, Lagos. I did my lower and higher diploma there. And that was my introduction.

Was there a crucial moment or point that you chose to commit to it as a profession?

I was already in my late twenties. I was a construction site supervisor for a construction company, and it was a good job. It was really good, so to say, in terms of pay and all that, and I was more or less financially secure. But I wasn't satisfied. I just felt something was missing. So I quit my job, and dropped everything, and went back to school.

How does it feel being in this situation now, looking back at that whole journey?

I'm one of those people who doesn't regret decisions. I just don't. Yes, I might regret certain things, but I don't dwell on it. Because I don't think dwelling on it is going to change the circumstances, I just want to make the best out of what I have. And also knowing that it is not a failure, it's just a lesson. So I just do it. I took that risk, and here we are. It was just more like a point in my life where I needed to make a point, take what I call "the quantum leap" and step into the unknown.

I knew, as a black artist here in Europe, it was not going to be an easy trip. Because, at the time, when I started doing this, I said, "Okay, I'm not going to do the general broad, whatever, fit into the regular art scene here." I don't follow the trend. I'm just doing my thing.

You never tried to adapt and blend in, so to speak?

I felt I wasn't meant to fit. It wasn't a decision, it was something that I’ve always known from the beginning. I just needed a sense of direction, so to say, in the sense of some sort of encouragement from somewhere. That came in the likes of Kerry James Marshall, as crazy as it might sound. There was an exhibition of his a couple of years ago, it’s been quite a while, in the Ludwig Museum here. And I saw it, and was like, whoa!

I was already doing something that was more in this direction, but it was more of me not being so sure of myself at the time. But yeah, I was trying to second-guess myself and then I saw his exhibition, and it was very much as if this guy just affirmed my belief. Just made it like, "Yeah, this is it." I knew what I wanted to do, but I guess I was just waiting for that small push. And it came in the form of Marshall. So, in my practice, I'm highly inspired by his work. The others I came to know much later. I didn't know about a lot of people. I guess, at one point, I realized that when you read too much, it's a plus, and also can be a minus to you.

Let’s talk about your choice of images. Are they scenes from your memory, photographs, or are they made up?

A lot of them are things that I remember, and I just create them from my head. But, yes, I do have photo references for some things. Not everything, but a handful of them.

How does the process look once you begin to develop that sketch on a canvas?

If I have the basic sketch that I want, the rest I just add as I go along. A lot of it happens on the canvas. And since I don't have photos for the faces, I paint them according to how I feel at that moment. Sometimes I do go and search for things like the lips. I search somewhere for something that looks perfect for the composition.

So, I take it from here and there, and put it together. I could look for how I can create some scenes, remember the photographs in the 1980s when we were growing up. I remember the photographs usually had this fancy wallpaper, but nobody would put those things up in this day and age anymore. Then I'll look back to those things and try to create them in my own way. By doing that, I don't follow the exact thing I see, I just make them as I go.

So, do you recreate them primarily because of their visual appeal, or is it more because of the emotions they bring up?

I have that on one side, and secondly, I just have a storyline that I want to follow. I have ABC, but I need XYZ in order to complete it, so how best can I arrange it?

There’s one I’m thinking of, and I was talking about it with a friend. I remember a particular spot where we used to buy oranges and stuff, and I'm like, "Do you still remember that place, is that guy still there?" And he goes, "Oh man, you don't want to know. He's still sitting there in that very spot. Same little bro, still selling his stuff. But now there is a newspaper stand next to him." I'm like, "You're kidding me." And he says, "No, there is a newspaper stand next to him." I asked if he could just go by and take a photograph. When I got this photograph with four guys that he sent to me, I'm thinking, okay I'm going to do something with it. All that wardrobe there, I just put them in there from head to toe. Tomorrow, I’ve imagined putting a lady in the picture. But I'm going to have somebody come by tomorrow, so that I can relate the rest of the fingers to the apple. Since it's the closest figure, I want certain things to be right.

Do you think that painting from your mental snapshots might have to do something with reconnecting with your past, especially your homeland?

With my past and present, and the fact that I'm so far from home. Another thing that actually kicks this whole thing off is the fact that I was barely 16 years old when I left home and moved to Lagos. I lived in Lagos for a very long time and I’d say I spent most of my middle teenage to adult age in Lagos. In that process, I studied and all that, and I barely spent more than one week in my own place.

Do you get homesick a lot?

Yes, I do, quite often. But a good thing with technology these days, you can talk to them, video chat with everybody. Have a conversation as if you were right there. You can literally see everything. Everything that goes on there, I literally know it. Sometimes even before they tell me, I find out from people who are already posting stuff.

Not like in those days when it took forever to get that done. I remember there used to be this old British canister, our postbox, as they call it. And you’d have to go and drop your letter in there. It might take a couple of days or weeks before the postmaster came to pick them all up. Then it would take months before whoever you wrote would get it.

Do you think that it might be, to some extent, therapeutic for you to paint these memories?

Yeah. At the moment, for me, it's more like a therapy. I'm doing it for my own well-being, but also I come from a culture where we don't write down our history. Our history is passed on orally, but I am not so eloquent when it comes to the art of telling a story. I'm all over the place, to be honest. So, for me, it's always better to put it in pictures. I can tell you about certain things and certain times.

And that works well because storytelling can kind of digress from the facts with time. Same happens with painting from memory, I guess? What we see on canvas is not exactly accurate either, right?

No, it might not be the exact same, but I like to bounce stuff back and forth. I sometimes like to juggle certain times and places.

In the beginning, when I started going in this direction, I did a painting of myself, a self-portrait thing. I did it with the foreground as the grass in my garden here, where I live, in Cologne, and the backdrop of my painting was the backyard of my family life in my place in Nigeria. So I fused those two together to create that. And the painting depicts me more like taking a bow, so to say. In my culture, we greet people by dipping our head. It's a sign of respect. It's nothing to do with belittling yourself or anything. I wanted the best way to depict the fact that—okay I'm here now, comfortable with who I am, just as well as where I come from. And regardless of where I find myself, I am who I am. That's it. And that painting, I called it Consciously Bowing.

"I'm doing it for my own well-being, but also I come from a culture where we don't write down our history."

How do you title the works, and how important are the titles for you?

Some ideas I have in advance, sometimes I come up with them as I go. But yeah, the titles are important. There are some works that I started with the idea of a particular title, but when they're done, it may not feel like it works for that title. I like one or two-word titles and do that quite often. I feel like using the words that best depict that moment in time, the words I feel represent that particular moment is what I would like to express.

Now that you have described making a painting that fuses your life here and your life back in Nigeria, do you see that as something in your future work?

Probably. Sometimes, when I start a piece, when I come up with an idea, I usually say, "Okay, the art of rendering for this work will probably be two or three different versions." It's an idea. So I will probably approach it from two or three different angles. There is a work that I did that I call Right of Passage. It's about the passing on and how, in my culture, when an older person dies, we believe that the masquerade embodies the spirits, and they come to lead the spirit of the dead to the other side. I like to touch all these parts of my culture.

Because, for me, what I'm doing right now is a way of documenting myself, and my life and my culture, for my son, and for the unborn, for those to come—so that it is not forgotten.

Tell us more about what motivates you to document all of this.

We adopt western culture a lot as we grow up. Of course, I have comfort with it, but I also saw it too often. It's a beautiful culture, but it's not our culture. And so there is always a conflict of interest because certain things are not practiced. And, I would say, if you're putting a square peg in a round hole, it just wouldn't fit.

Our orientations are directly opposite of each other, and people don't consciously understand that. For a lot of Africans coming to the European culture, you have to actually kind of adapt to European culture in order to function in the society. So you will say, "Okay, I blend into the new society." But that is not often the case when a European goes to Africa. He is not changing, but the Africans are forced to change their way in order to suit his needs, which is wrong.

How do westerners or Europeans react to your imagery? Do they have a conflict understanding or accepting it?

There are several ways. I've been asked sometimes, "Why do you only paint black people, why don't you paint white people?" And I’ve said, "Right now, in my head, that's all I see." I want to get that picture out of my head. I have so much in my head that I'm not done with, ideas that are still rumbling in my head. Maybe when I'm out of ideas, I might shift. There will be points where there will be white people in my paintings, definitely. That's coming. I'm just not there yet. But right now my mental state is not present in this place.

Let's say I'm not a progressive person, I'm an old school one. I think old school. And so when it is time for me to think that this is now the old school of the near future, I might treat it.

I heard something similar when I spoke to Esiri Erheriene-Essi who reflected that she enjoyed going to museums but nobody in the pictures looked like her or most of the people in her life.

Yeah, Kerry James Marshall said that. The same thing happened when I came here, and I walked through the museums, and I couldn't see anything that I could relate to. The only time I see a picture of a Black man, it's the servant or something. I understand that you see us like this. But this is not who we are. Because that is just a fraction of my people.

Most of what western people see in museums is work that is familiar, and, for some, when they see the work of an artist who paints Black people, it's disconcerting. But many people didn’t notice for hundreds of years that Black people were missing from the paintings…

People ask about that question, and for me, the moment of that realization is an affirmation of my conviction that what I'm doing is the right thing. I'm going to continue doing it. Because I do question myself, “Is this going to be receptive?” In the beginning, yes, I did have that conflict. I questioned myself. But then I realized, “Oh no, man, I don't have to.” I don't have to justify why I paint the way I paint to anybody. Not at all. I don't owe an explanation. I'm just going to do my thing, and here we are.

Peter Uka's newest solo show, Inner Frame, is on view now at Galerie Voss in Dusseldorf, Germany through October 24, 2020. He is also represented by Marianne Ibrahim in Chicago.

Peter Uka's newest solo show, Inner Frame, is on view now at Galerie Voss in Dusseldorf, Germany through October 24, 2020. He is also represented by Marianne Ibrahim in Chicago.