Luke Pelletier

The IDea Man

Interview by Eben Benson // Portrait by Brandon Forest Jenson

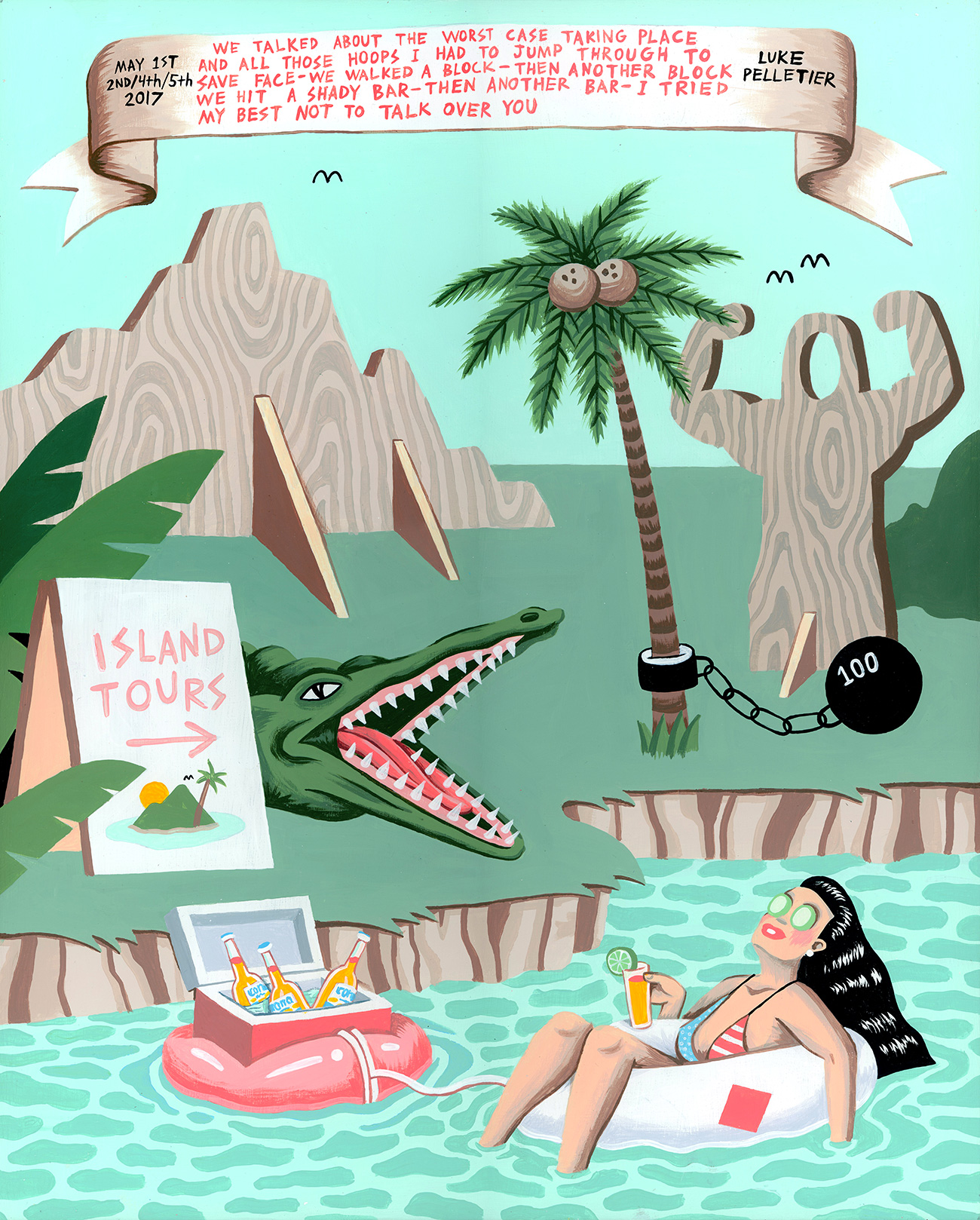

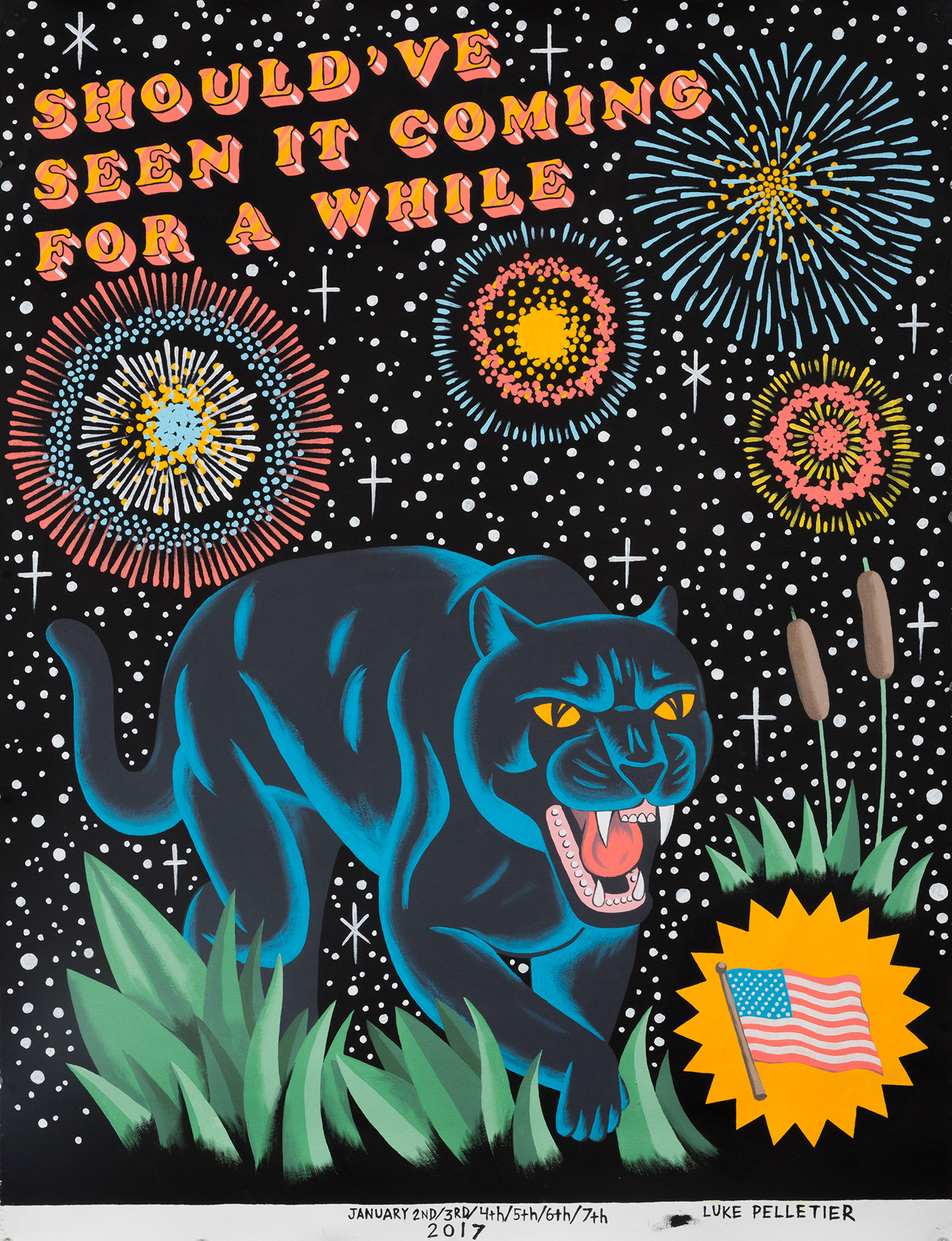

Nostalgia for youth is a potent force, a pure vision of what life could be if only we could return to that place. It disregards harsh realities, while embracing the joy, romanticizing the pain. It turns sensual memories into towering symbols that stay with us forever, shaping the values, goals, and hobbies that bring us joy in adulthood. Luke Pelletier unearths this world and these memories, tempers them, but ultimately invites us to hang out back there with him. Growing up in rural North Carolina, Luke’s reality was shaped and formed by the confluence of punk and skateboarding with traditional American values. His work playfully incorporates sentimentality and Americana, contrasting them with the inner conflicts of growing as a person and as a man.

Eben Benson: I feel like, with looming adulthood, there's this urgency to work tirelessly towards goals, regardless of whether they’re wanted or valued. You seem scattered, though in a good way, so no one can doubt your prolific work ethic. When did you realize you were unable to or simply unwilling to just work towards something for the sake of working?

Luke Pelletier: I think I’ve always had a similarly scattered and driven personality. I loved art, but for a long time, I didn’t really know where art came from or that people could be artists. There aren’t many art museums in the South and if there are, I wasn’t going to them. I never really saw anyone making art around me. It all just seemed really impossible. So it’s hard for me to pinpoint when I realized I wanted to be an artist. Even though I didn’t know about fine art, I knew I didn’t want to work a normal job. So I’d come up with little schemes to make money. When I was a kid, like second grade probably, my school banned Pokemon cards. All the kids had their lunch money or whatever. I’d get a stack of notecards from the library and I’d draw some pretty alright looking trading cards and sell ’em for a dollar each, or three for two. The kids would trade them and try to pay extra for better cards. Pretty soon, I cleared a hundred dollars off of these bootleg Pokemon cards.

That was a fortune to me at the time. Then the other kids’ parents started complaining because their kids were coming home hungry after they blew all their money on my cards. I had to have a meeting with the principal and my mom. He told me I had to give all the money to this charity the school was doing. I agreed, but I never did. The little shit that I was, I kept the money and I felt like I outsmarted an authority figure.

I just liked all of it. The creativity. The hustle. Breaking rules. Making money. Once I started to realize that I could make things that were fulfilling to me but also operated as a part of some sort of culture, I became hooked. I got hooked on learning to make new things, throwing parties, blacksmithing, taking photos, expressing myself, opening businesses, printmaking, watching my ideas fall apart, coming up with new ones, watching my business fail, doing design work, coming up with new business plans, starting bands, pitching TV shows, learning new instruments, writing better songs, going on tour, making paintings, taking photos, working with my friends, getting fucked over, learning new techniques, collaborating with other people, curating art shows, learning how not to get fucked over, running an offset press, and throwing everything I’ve got into being creative. I’ve always done a million things at the same time. I’ve tried to narrow my focus in the past, but the boredom and restlessness become unrelenting. I don’t really have religion. At least not my parents’ religion. So if I find meaning in anything at all, it’s in the things I make and the work I do. I guess that’s what keeps me going.

How does your somewhat traditional background, coming from rural North Carolina, interact with your identity as a skate rat, artist, or idea man? Growing up, I always felt the tension there, especially with my parents. Where do you see elements of your rural upbringing in your work?

I think I always felt like an outsider in North Carolina because I wasn’t actually born there. I moved there when I was seven years old from Tampa, Florida. My parents didn’t know anyone when we moved to Brevard. The town is really small. Everyone knows everyone and they’ve known each other their whole lives. No one ever did anything specific to make me feel like I wasn’t a part of the community, but I always knew I wasn’t. My parents were always real cool about everything. They encouraged me to draw and they let my shitty hardcore band practice in our basement. I knew they thought the stuff I was making was weird and the music sounded like hell, but they just let me be weird. I never got much grief from them, but I got it from everyone else.

I had a real problem with a lot of the things I saw growing up in the South, and I had a hard time keeping it to myself. Most of the people I’d hang out with were down to earth, but you didn’t have to look far to see some dumbass with a rebel flag tattoo who felt like he was put on earth to build a wall and keep the government small. Even though I thought I was so much “holier than thou” because I didn’t have a “the south will rise again” bumper sticker, I’d never heard the word feminism until I went to college at SAIC in Chicago. So I had a lot of catching up to do as well.

A few years after we moved there, a lot of the factories in the town started closing down. It seemed like the whole town was out of work for a while, and that didn’t help ease any of the tension. But then the town started to rebrand itself as a tourist spot. They cleaned up the downtown area, opened up some bars, and built a bike path. After that, the whole town was operating on a seasonal economy. Every winter the shops close and the town dies, but every summer the tourists return and it comes back to life. I still make a lot of art about all of that stuff. You can hear it more in my music and see it more in my pictures, but I’ve always painted pretty heavily about seasonal economies and tourist culture. A lot of my inspiration comes from the flea markets I visit in the South, the hand painted signage, building materials, alligators, and hard work. The South is a complicated place, but it’s where I’m from. I think it’d be hard for me to make anything that doesn’t have some sort of reference to how and where I grew up.

I read that Tony Hawk's Pro Skater was a piece of your childhood that affected your view of the world a lot, and that nailed a huge feeling for me. I love you saying that your work aims to create the world that you kind of found out didn't exist. How is that going? How do you find that ideal world has changed?

Yeah! That game was huge for me. I was wicked young when I first played it, so it was sort of my first introduction to skateboarding and punk. The game created this whole world that was designed for skating. All of the music was so energetic and new to me. You’d be skating crazy impossible obstacles and smashing through windows. It was this perfect teenage paradise with no rules. It wasn’t long after that when I actually got into skateboarding and punk. I fully bought into all of it. My friends and I started some crappy bands. And when we weren’t practicing, we’d go skating uptown or hang out at the skate park. The people who owned the park gave my older brother a job and they let us play shows whenever we wanted. So that sort of became our second home for a while.

That game and a lot of my other interests, like flea markets, tourist towns, themed restaurants, amusement parks, mini golf, and things like that definitely got me interested in the idea of a constructed paradise—places where every detail seems considered. They provide you with an experience you can’t get anywhere else. I guess that’s what I’ve always been working towards. I’ve made some attempts at building my own world a few times. The last time I did it was at New Image Art for my last solo show. I was happy with how it came out, but it was only up for two weeks. In the future, I’d like to open something that people can enjoy for a longer period of time, and I’d like to find business partners that I feel like I can trust. I’ve watched a few projects crash and burn because I brought on people who couldn’t deliver what they promised. Whatever I’m working towards has never been a fixed thing. If I go on a walk today and see some really awesome shutters, I’ll go home and redesign the shutters on the bar I’ve been working on. I’m a scattered person, so it’s always changing.

It seems like you were meant to be in California. What made you move to Los Angeles?

I’ve wanted to live in Los Angeles for as long as I can remember. A lot of that came from being into punk and skateboarding because that’s where all my favorite bands and skaters were, but I had no reference for it other than what I saw in movies. So I always had this picture in my head of what the city was like. Most of that came from Beverly Hills Cop, Dogtown And Z-Boys, Fast Times At Ridgemont High, Boyz In The Hood, and Crocodile Dundee 3. But it’s been a lot more like a cross between Less Than Zero and an episode of The Beverly Hillbillies.

It’s a trip out here. There are palm trees everywhere so it feels like you’re always on vacation. People smoke weed outside of bars like they’re smoking cigarettes. Everywhere you go, it’s like having déjà vu because you’ve been there before in some movie you can’t recall. I’ve never seen so many people with so much money in all my life. They own whole streets and they pack them with mansions, but if you go a few blocks in any direction, you’re walking into another world. I’ve eaten food out here that looks like it’s out of a science fiction movie, and been introduced to a culture I’ve never even heard of at the same time. It’s not a very integrated city, but it’s very diverse. Every neighborhood is different and the creative communities are so energetic. There are a lot of really great DIY art and music spaces in LA, so there’s always cool art to see and good music to listen to, but, across the board, this city charges way too much for beer. When I tell the boys back home that people are buying eight-dollar beers, they lose their minds.

Growing up skateboarding, what were some notable graphics you remember? Were there any companies or artists that really stood out to you in the skate world?

I don’t even think I was born when it came out, but my favorite graphic, hands down, is American Icons by Marc McKee. As far as companies I thought were cool, I really liked enjoi. That Jason Adams part in the Bag of Suck video was always one of my favorites. And I liked the way they did those funny intros with the bootleg special effects. Ed Templeton and Toy Machine, of course. We must have watched that Baker 3 video a thousand times at the park. And I know they weren’t a skate team or whatever, but the whole Jackass thing really resonated with my friends and me. We were mostly skating in parking lots and stuff like that. So we’d get bored and copy all the dumb shopping cart stunts they warned us against. We’d come up with our own stunts and film them while we were out skating. I was more into skating that seemed creative and fun rather than technical. A big part of that might have been because I was never all that good at it.

In the past, you've spoken about how the internet gave you access to so many things that influenced you growing up. Obviously, the internet has changed a lot, and so have you. How do you feel about the internet and Instagram these days? Where do you see it helping young artists and where do you see it hindering them?

Most of what I learned about skateboarding and punk came from the internet. There just wasn’t a lot of information about that stuff lying around the South. Other than my friends, no one was really into it. Not only were we able to find songs and videos, but if we wanted to build a quarter pipe or find out when bands were coming to our area, it had all that. Once my band started playing shows, we used the internet to set up shows and promote them. That’s when I started learning Photoshop, coding, and all that, so I could make my band’s website look cooler. As far as Instagram goes, I think it’s great! It’s cool to be able to keep in touch with artists from around the world. I feel like I’m a part of a scene that’s a lot bigger than the city I live in. My biggest beef with the internet is that everyone is looking at the same stuff. I feel like every artist uses Google images at some point or another to find reference images. And that’s fine, but you end up seeing the same breaching shark photo done in the style of twenty different artists. I’m trying to get away from that a bit, but it’s hard to justify going to the library for a picture of a shark or trying to take one of your own when you have 10,000 images of sharks on your phone.

Do you still like to build things? How do you treat building something for utility versus making something aesthetically pleasing?

I love building things! I try to do that as frequently as I can. How I approach it depends on what I’m building. If I’m building a bar, I have to take into account the lighting, the size, the materials, the fact that people will be spilling drinks on it, the possibility of people dancing on it, how people operate in the space, aesthetics, stability, and heaps of measurements. Making paintings is great, but there’s no better feeling than watching your friends get drunk at a bar you’ve built

When we met, you gave me a matchbook (also a business card) that referred to you as an idea man. What's a common idea that's been recurring for you recently? Do you find the same thought or theme floating around your head for months at a time, or is it always spontaneous?

If feel like I’m always sort of thinking about labor, competition, tourist culture, capitalism, vices, romance, moral dilemmas with romance, objectification, addiction, free will, masculinity, fun, and ultimately, Americana. When I wake up, I usually continue to work on whatever I was working on the night before. Ideas and lyrics come to me throughout the day and I try my best to write them all down. Sometimes I write them directly on the painting I’m working on and sometimes they end up on a list. I put the really good ones on a separate list so they don’t get pushed to the side. At some point, every day, I work on the lists I already have. Sometimes I just put similar ideas near each other so I can make connections and combine them into a single idea later on, or I work on developing an individual idea. Some ideas have been on the list for five or six years and have no chance of ever seeing the light of day. So there’s a spontaneity to how I come up with things, but it’s also fussed over for months.

Luke Pelletier’s newest solo show, American Fizzle, opens at New Image Art in Los Angeles in February, 2018.