Koak

Bodies in Muse and Motion

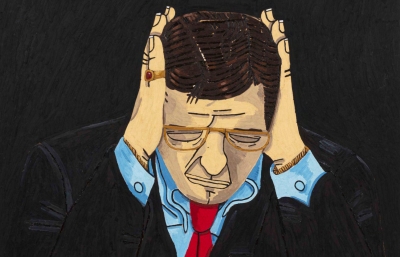

Interview by Jessica Ross // Portrait by Maria Kanevskaya

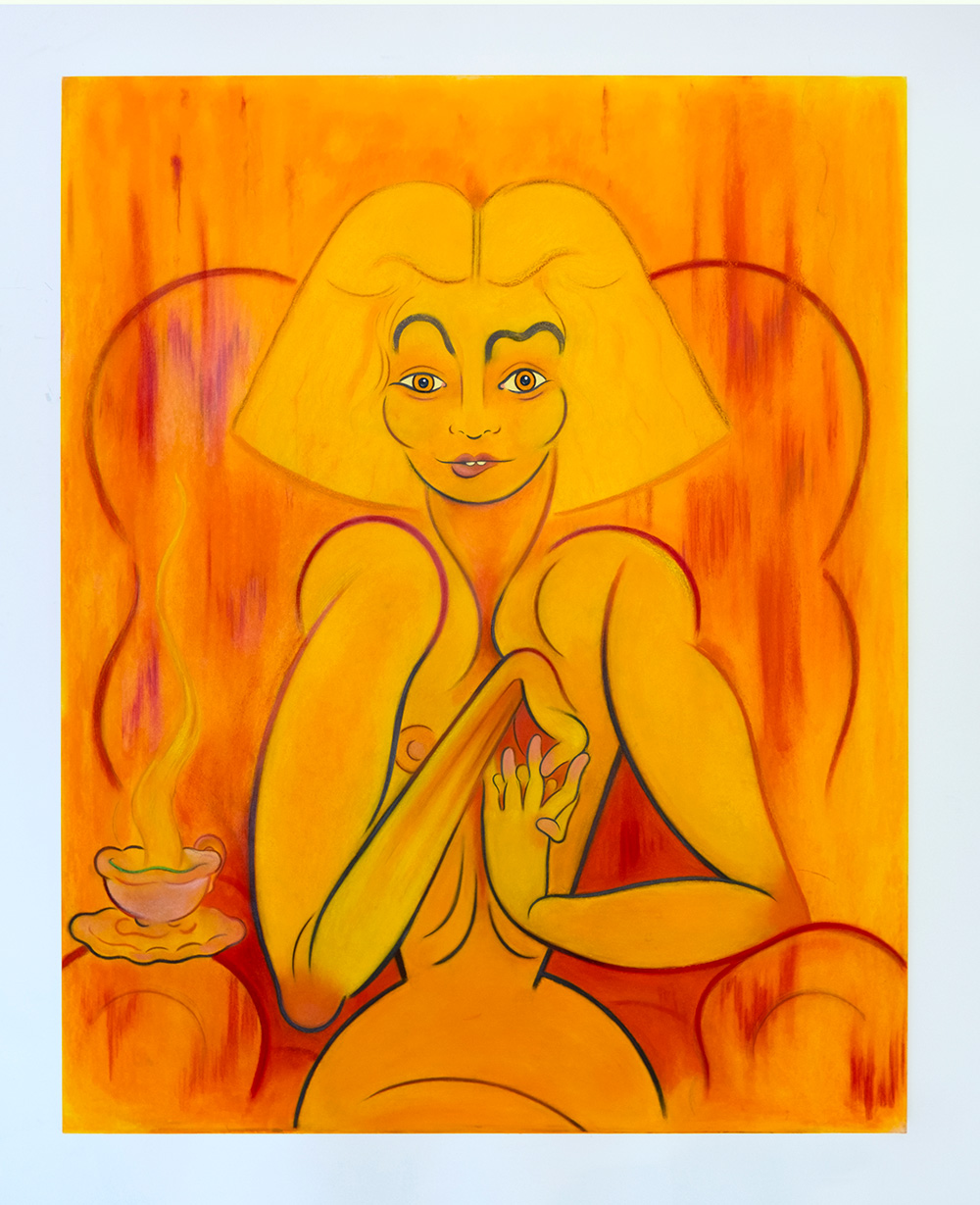

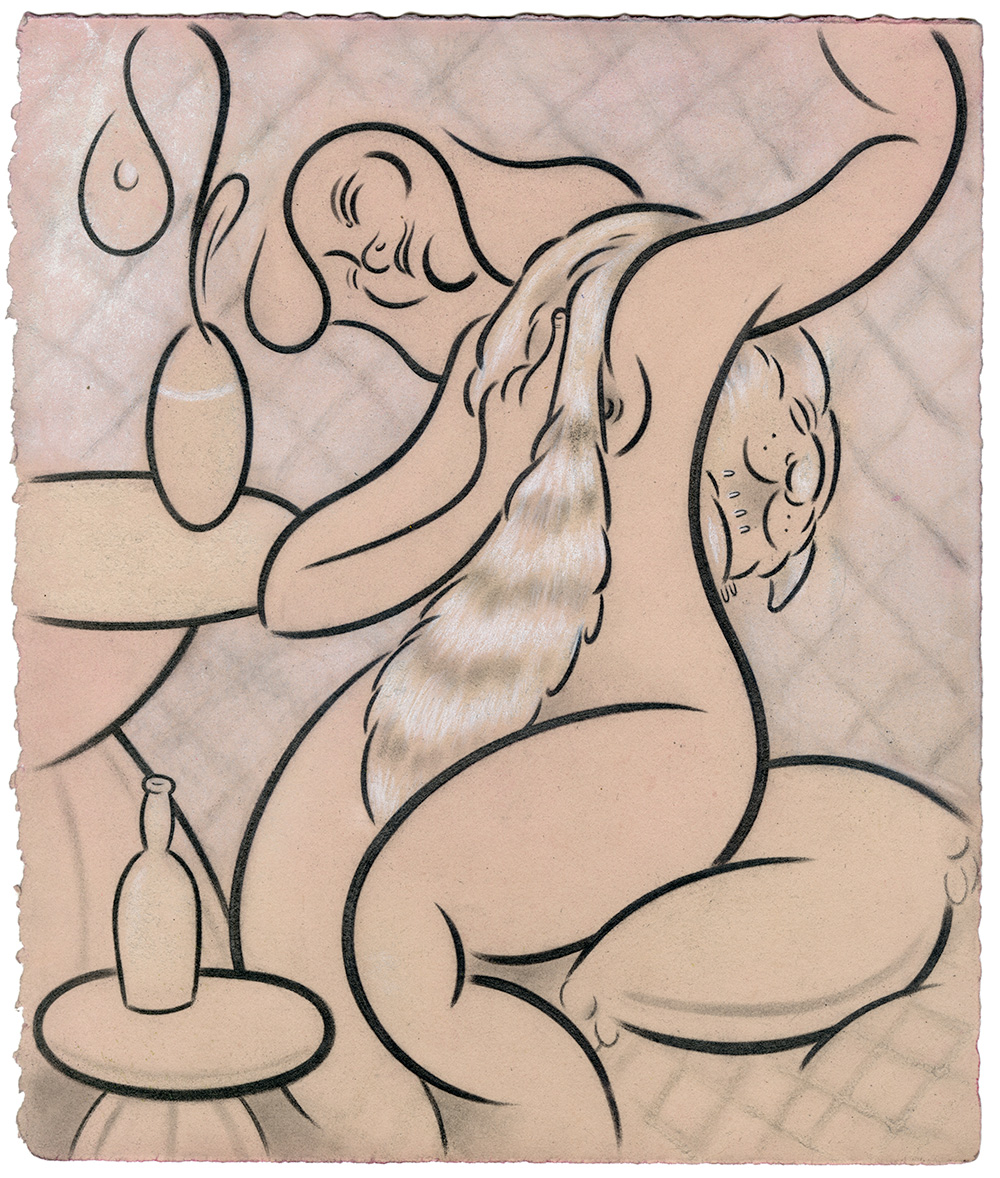

I’ll be honest, the whole “artist and muse” relationship is a little irksome. Wander the halls of any museum and you find countless classical portraits of women: women bathing, women dancing, women reclining—all demure and stylized, just as the artist intended. Created by men, for men. It’s these idealized depictions of female-ness that are antagonizing, making me resentful of this historical weight. San Francisco-based artist Koak, with her MFA in comics, liberates her women.

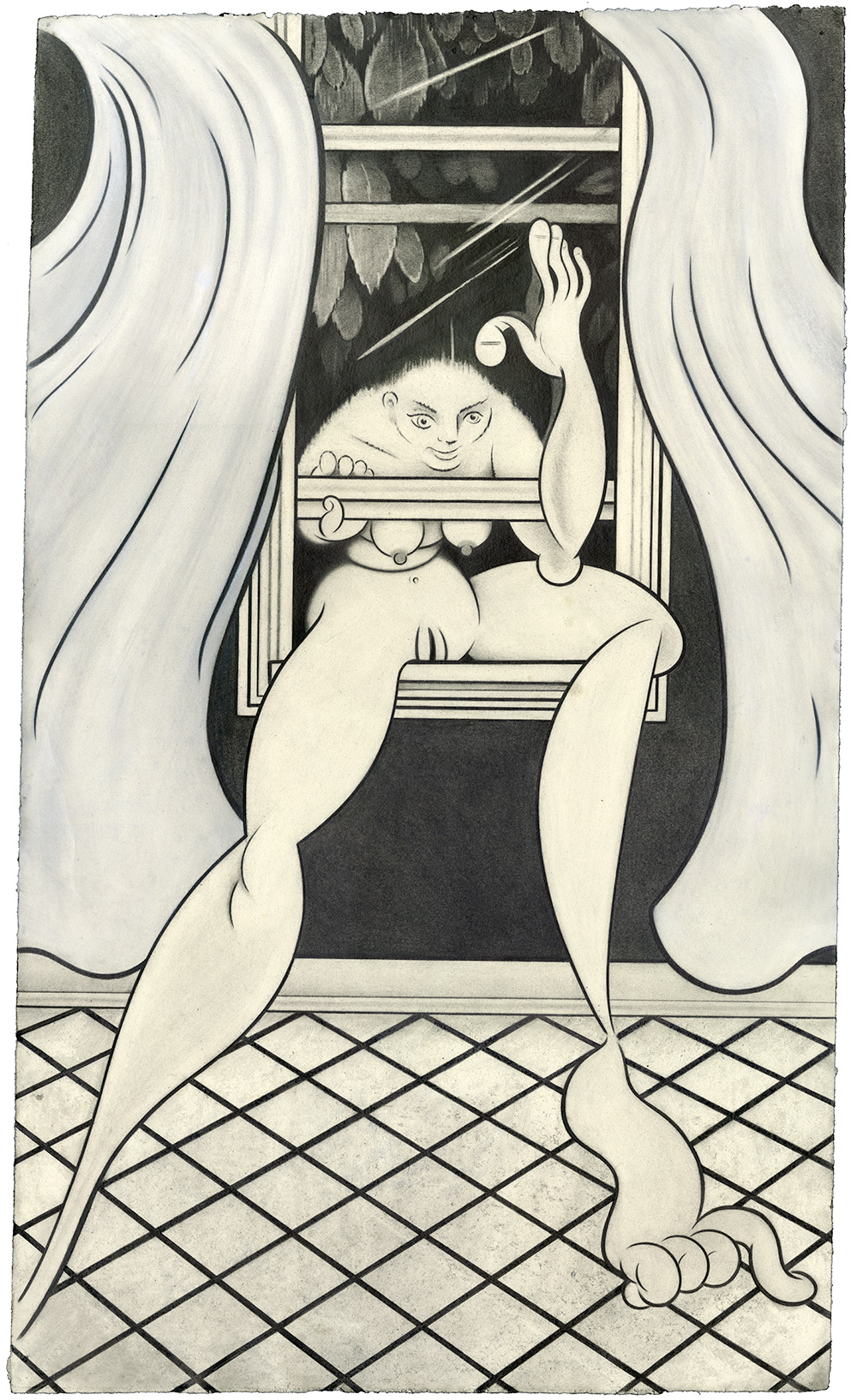

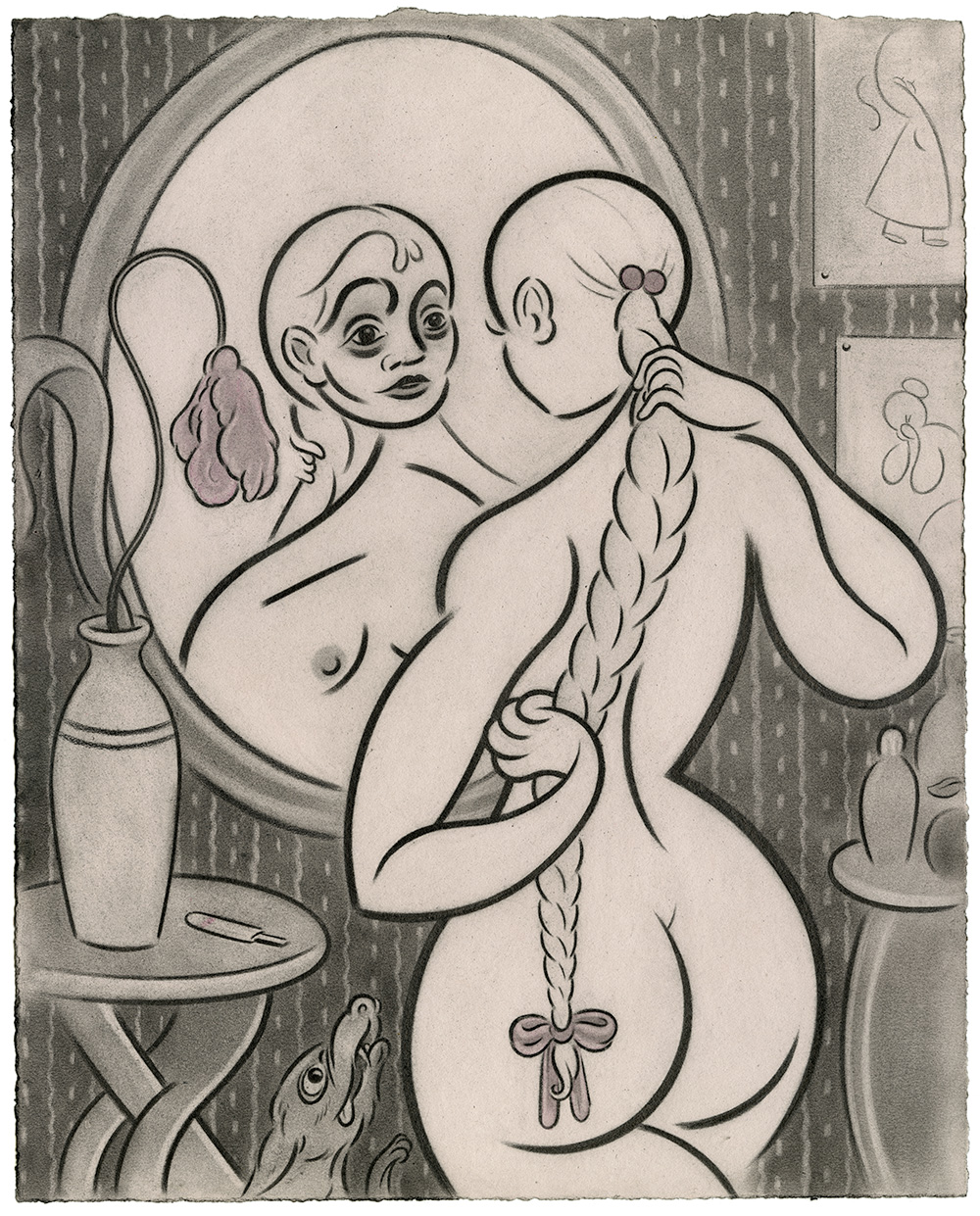

Working in a range of mediums, Koak’s paintings of women vibrate with hyper-presence, even in an abstracted, amorphous state. Reclaiming agency one brush stroke at a time, Koak portrays women through a more thoughtful, honest lens. In her paintings, she fleshes out her ideas and feelings, and with each twisting limb and irregular feature, communicates raw vulnerability and engages her viewers in what it means to be human. Following some killer shows and projects this last year, we sat down for a frank conversation about the inherent power play that exists between artist and subject, the ever-present stigma associated with comics, and the therapeutic nature of creating.

Jessica Ross: What are some of your earliest memories creating? Do you have a defining moment in your life when something clicked, or was it a more gradual process?

Koak: I was sick a lot as a kid and remember staying home from school and drawing from comics. The women of X-Men were my favorite, especially Storm. Looking back, there was probably a connection between the lack of power I felt at the time and what these women symbolized.

When I was a teen, I started making zines that I sold at Caffe Pergolesi, a coffee shop in Santa Cruz that was a sort of safe haven for local artists and musicians. It’s also where I had my first exhibition. There was something about the act of making work and then sharing it with others that gave purpose to what I was doing. I had always had an incredibly hard time communicating with people, and suddenly I had found this language where not only was I able to express myself, but people could understand, and, more importantly, they could connect. As a young girl, I didn’t really feel like I had any power over my life, so finding a voice that empowered both myself and others was a sort of magic in its own way.

True connection is so vital when you’re growing up. Is there anything you want to say to your teen self now that you’re a bit older and wiser?

I wouldn’t say anything to myself as a teen. I have regrets, but that’s how we learn—navigating those difficulties is part of what shapes us.

I always get a tinge of uneasiness when I see your work. There’s a tension that seems to linger, something about the figures’ awkward physicality—beautiful but challenging. Was this an intentional move on your part, or am I just a weirdo?

I am always trying to create moments of tension in my work, because without conflict, it would be one-note. To me, it is extremely important that the figures do not exist in a single state of emotion, as I find that to be very rare in life. Most things are not easily defined or boxed neatly into their own distinct categories, so to make work without tension would be to make something that I feel would be very alienating and dishonest to life.

Sometimes I like to think of it as if we all contain a host of necessary archetypes within ourselves. Specialized roles, developed specifically for us, that bubble up to the surface when necessary. I think this sort of duality coming to light through a single figure is in part what creates that form of tension in my work.

But, luckily for you, you’re probably also partially a weirdo.

Providing agency to female subjects is a driving theme in your work. Since smashing the patriarchy is not an overnight affair, why do you think it’s important to shift the way women are depicted in art?

I don’t know if I would say it’s as necessary to shift the way women are depicted in art as much as it is to shift the narratives that are being told. When the overwhelming voice of stories comes from a small pool of individuals, we are getting only a very limited experience through art of what it is to be human.

Historical portraiture of women has overwhelmingly been framed by the male conception of what it is to be female, the same voice that for centuries has treated those muses as property or lesser citizens. Providing agency to the women in my work is important, not only because it gives them purpose and a sense of life on the page, but also because, without agency, I would not be able to be a creator. There’s a kinship between me and the women I’m drawing because I am not an outside figure looking in at them.

Are there any other women or non-binary artists who really inspire you at the moment?

I’ve been very lucky to meet and work with some amazing women through the gallery that my partner ran: Brook Hsu, Mattea Perrotta, Alexandra Tarver, Mindy Rose Schwartz, to name a few. My friend from college, Nicole Miller, just opened a show at CAAM in LA that I’m excited to see.

What is it about creating work that you find to be therapeutic? There’s definitely a lot of raw emotion revealed in your drawings and paintings. Is there a methodology or approach you take when fleshing out your own experiences?

When I was younger, my work was very much drawn from my own experiences, and that was an act of therapy. In those early zines and exhibitions, I was dealing with unpacking all the difficulties of being a teenager. Some of my closest friends were struggling with addiction and I felt helpless in giving them support. I was also unraveling the buried pain of having been abused by my biological father, who had been in my life only as a distant figure since I was two. Creating work that grappled with things that felt insurmountably painful, often with a layer of comic humor, gave me an outlet for this sort of pressure that otherwise may have caused me to explode.

Since then, my work and interests have shifted, evolving into something more detached from my own experiences. Recently, my focus is on universal narratives and archetypes that encapsulate the feminine—experiences heard from friends or caught through the news. There is still an act of therapy in creating the work, I have to be very present and allow myself the space to create the emotion needed to give over to the page. The method, I think, is to feel and tap into states of being, which can be very taxing sometimes. Our culture has strict, unspoken rules about when, where, and in what context emotions are appropriate, but I would not be able to make these things if I did not give myself the space to feel them. It’s funny—I think I would be a terrible actor. I have the worst stage fright, but I am very good at sitting alone in a room and conjuring up a flurry of emotions from my past.

What do you listen to in the studio? Is it podcasts or playlists for you?

Today, Victoria Spivey. Yesterday, Brian Eno. Tomorrow, maybe Shilpa Ray.

Since you and your partner, Kevin Krueger, opened the now-closed Alter Space in 2011, can you describe what it was like starting a gallery? And how might it have influenced your own practice?

Rough. Running an art space properly, supporting the artists you’re working with, takes everything you have. At the time, I was not exhibiting or sharing my work, so putting all of my energy into doing things for other artists that I wasn’t able to do for myself was difficult. But we went into it always knowing that I would leave and Kevin would take over. He’s the one with an eye for finding brilliant people to work with and curating great exhibitions. Watching him work, from behind the scenes, has given me so much appreciation for how galleries run and the dedication that it takes to make them work.

It’s influenced me in that I’ve really gotten to see all the ways that different types of artists approach their work and problem solving. It’s made me hyper-aware of the ways I work, and taught me that some of my ingrained habits are useless. I’ve always been very interested in the ways different brains work, so watching how artists I admire think has been very influential.

You seem to utilize almost every medium (pastel, charcoal, oil, etc.) At the moment, what’s a favorite in your toolbox?

Tombow’s sanding eraser. It can cure anything.

I’ve asked this question before, but it’s worth repeating. I’m sure, as a female artist, you get a range of idiotic and downright misogynist comments surrounding the provocative and sexual nature of your work. What’s your response to those people, or perhaps other female artists working in similar subject matter?

Part of sharing your work publicly is relinquishing its narrative. During my first exhibition at Pergolesi, I built a comment box and put it out with the invitation for people to respond. Some of my favorite comments were from people who got really mad about the work, where it just got under their skin and they couldn’t let it go. I don’t say that from a place of cruelty—I didn’t make the work to distress people. But it meant that they were thinking, that there was something about the work that took them, however momentarily, out of their comfort zone, and in that way, it was a compliment.

I know this is a little different than dealing with creeps and misogynists online, and I don’t mean in any way to make light of some of the horrifying things female artists have to deal with. But for me, the best thing to do with people like that has been to give them nothing, because honestly, their opinion to me is nothing. Whatever anger or frustration I feel from their interaction with me, I put aside and save for the next time I want to make a piece that needs that anger. Using my voice to shout down some internet vortex is pointless; using it to make work that talks to other humans who have been through the same thing is the reason I make work.

You’ve been in the Bay Area for quite some time now, and the ubiquitous question is about how the tech scene displaced the art scene in SF. Instead, I’d rather know what cool new things you have seen pop up in the last few years. What’s happening creatively in the Bay right now?

There’s been so many wonderful artist-run spaces that have opened up over the last few years, ones that address the difficulties of running a space in a city with such high overhead. Cloaca Projects, which my friend Charlie Leese runs out of a shipping container behind his studio, and Nook Gallery, which is run by Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo out of her kitchen, to name a few. Kevin is also moving on from Alter Space to partner with Et al., an amazing SF-based gallery that has two spaces in the city.

Your drawings read as comics, in that you can follow each line and arrive at different narratives. It’s very approachable and understandable for the viewer. Obviously your MFA in comics, I’m sure, has something to do with it. Why do you love comics so much? What about them just pulls you in?

I’ve always been drawn to the underdog, or the thing that has the grit of being an outsider. There are certain constructs in society that are just so perplexingly “off” that they pull me in, like a math equation of social norms that doesn’t fit. The U.S., with its strange relationship to comics, is one of these. Here’s an art form that combines visual art and literature—two of the highest forms of art—and yet somehow, through that combination, it becomes less. This conundrum is fascinating to me, and even as comics are now becoming more of a staple, part of my love for them will always be their ugly duckling status.

There’s also the added pull that, at its heart, comics are the act of telling stories through a visual language, and storytelling is one of the most powerful tools we have to connect to others. They are entirely about how we convey narrative and emotion through the use of static lines, shapes, and tones—and their meaning shifts depending on those visual elements. Comics are a fascinating puzzle about the use of space and static imagery to create language.

What are some of your all-time favorite comics or graphic novels?

Bottomless Bellybutton and BodyWorld by Dash Shaw. Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life by Ulli Lust.

You’ve said in the past that you’re not necessarily flattered by being compared to Picasso. Can you elaborate on that a bit?

Yes, I think Picasso’s work is great, but I don’t believe that something in the realm of figurative abstraction should be necessarily lumped under his totem. There are too many brilliant artists that were just as talented, had just as significant voices. To look at figurative work that plays with abstraction and just see Picasso is a simplification of the world and a disregard of nuance. It also generally tends to come from men, and from men that only look at the surface of things, who are focused on style over substance.

To some extent, the term salt in the wound comes to mind. Here’s a man who told his lover that women were either “goddesses or doormats,” who referred to us as “machines for suffering.” I’ve read so many articles where his friends or family recount his obsession with submissive women, and this ability to take the life from those around him in order to feed his work. That’s the opposite of what I am trying to do. When I work, it is my intention to make something that sparks the feeling of life in the viewer, to empower women, not to capture and suppress them for my own gain. To give back something that maybe this world has taken away.

koak.net