Haroshi

The Building Blocks of Life

Interview and portrait by Evan Pricco // Translation by NANZUKA Gallery

There is probably enough evidence around the art world to suggest a working artist, with a schedule of exhibitions and resume full of projects is, in a way, living that dream you pursued at a younger age. I’m not talking about the stress and anxiety of creative output, because that is a beast we cannot ignore. I’m talking about that youthful energy to create something, envisioned by oneself as a working artist and doing whatever it takes to make that your life. In this idea, there may not be another artist quite like Tokyo-based Haroshi, who has taken a lifelong and youthful obsession with skateboarding and literally made it the backbone and infrastructure of everything he does in the art world.

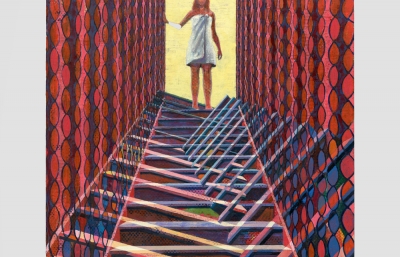

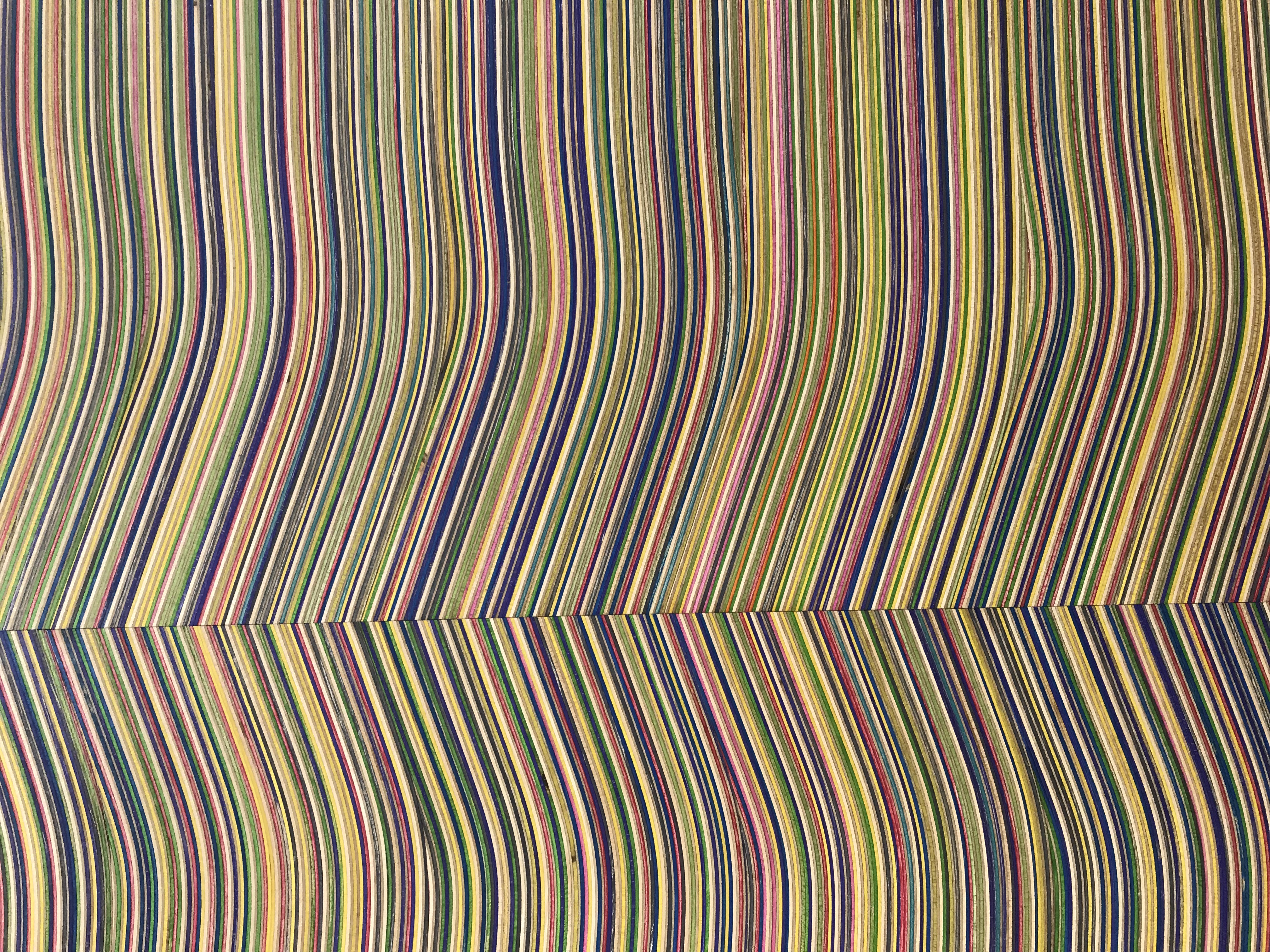

Calling Haroshi a sculptor seems too simple, because he is a collector, architect, painter and industrial designer, as well. What he has done throughout his career is take recycled skateboard decks, transforming and crafting them into sculptures that range from classic graphics, pop iconography, installations, and the present, where he currently recreates Japanese toys, including those from childhood. In a way, he is fashioning a toy within a toy, a collectible of a collectible, all with the incredible remolding of skateboard plywood materials. We visited Haroshi’s studio on the outskirts of Tokyo, watched his intricate new carving and shaping methods, explored his newly purchased, vintage Japanese toys… and watched him skate his studio ramp.

Evan Pricco: I wanted to start with this question about growing up in Japan. At what point do kids begin to realize how much craftsmanship means to their culture?

Haroshi: Whether willing or not, as a child growing up in Japan, you have many opportunities to come into contact with things made from wood by the hands of craftsmen. When there’s a festival, you walk the streets carrying on your shoulders a Mikoshi (a divine palanquin for the deities) made by craftsmen, and at New Year’s, it is customary for people to pay a visit to the shrine. Japan has a culture rich in handcrafted things that are both traditional and unique, and I feel that perhaps that is why craftsmanship is so deeply ingrained within our daily lives. Also, many Japanese craftsmen in the past used to be covered in tattoos, and at the time, I found myself totally mesmerized by their coolness. It’s kind of like craftsmen have a world of their own and aren’t trying to please anyone.

Was there something in your childhood, specifically, where you made the connection of how well things are made? Because your work takes so much time and is really rooted in a craft of sculpture making, I wonder what you saw as a youth that helped shaped your process?

As a child, I was physically very weak. I always found myself in the hospital, and I wasn’t very good at sports. My only forte was handcrafts, and that’s why each year during the summer holidays, my grandfather and I would come up with different themes and read books about woodworking to make various things together. I even made a skateboard that came equipped with a handle. I remember it being painted black with a red lightning bolt motif on it. It wasn’t your typical elementary school kid design [laughs].

My grandfather was someone who’d make everything and anything, even from the point of crafting the very tools that he used. One day, I saw him carrying a really long stick on his bicycle, so I followed him to find out where he was going. He eventually stopped at the park, where I noticed that the stick was structurally made so that it could be elongated. He then used this stick and proceeded to knock down all the tennis balls that had been caught in places high up and out of reach. That’s when I realized why there were mountains of tennis balls in our house. The things my grandfather made weren’t perfect, but I had found them to be very fascinating. He was a great influence on me.

Before the skating started, were you into any sort of traditional or non-traditional art?

I more or less made whatever I wanted because we weren’t that wealthy [laughs]. When I told my grandfather that there was a particular colored bicycle that I wanted, he bought the same color of paint, and we then used it to paint my own bicycle. When I said that I wanted to make my Mini 4WD more lightweight, we went to the flea market together to buy a drill. Since I loved to make things as a child, my grandfather let me take lessons at a nearby craft workshop when I was in elementary school. I suppose that was both my entrance and exit into the world of art, because I soon had to quit attending.

At one time, there was this event at the workshop where all the kids made little wooden mazes in order to compete to see who could be the first to get the pinball to the goal. After thinking long and hard, I decided to secretly practice a way to make the ball jump straight from its starting position into the goal, instead of rolling it along the maze. On that day, while others took around 30 seconds to reach the goal, I finished first place in just two seconds. I thought I’d won by a landslide, but the teacher made me stay behind after class, and I was badly scolded for about an hour [laughs]. I was told that I shouldn’t cheat. I really didn’t understand what I’d done wrong, and figured that I could no longer stay in a place like this. That’s how my art experience had ended in a flash.

Also, I can’t exactly remember why, but when someone had given us free tickets so I could attend a museum for the first time, I got appendicitis and suddenly had to be rushed off to hospital in an ambulance. I guess art and I didn't really bode well.

I almost feel bad I asked! Okay, let’s divert to where you are now. I don’t want this to get too upsetting. I want to talk about toys a little bit because your newest work revolves around the finding of these vintage toys and reimagining them. Did you collect toys as a kid?

Yes, I collected lots of toys! They weren’t really a collection per se, because I was quite hard on them, and had played with them a lot. They were entirely consumable. After fierce battles, their arms or heads would break off, so in the end, I just threw them away. As I recall, the first toy bought for me was a Tiger Mask figure from the Chogokin series manufactured by Popy. After that, I had an obsession with Kinnikuman (Muscle Man) and Gundam erasers. I also got into plastic models of tanks, but the first military model I bought was of a German M24 hand grenade, which I really messed up in assembling [laughs]. I don’t know why, but at the time, my father seemed to be into making plastic models of temples, and although Kinkaku-ji (the Temple of the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto) had reminded me a bit of the MSN-00100 Gundam mobile suite, I really didn’t understand what it was about them that he found so interesting. My father and I were both into making all sorts of weird models.

How actively do you collect these toys now? Are you, like, on eBay all the time?

I did search for the American Buddy Lee dolls on eBay, although I buy most of the Japanese soft vinyl toys on a website which is like the Japanese equivalent of eBay. You usually don’t find any broken toys in the secondhand shops. Most of the toys I use are vintage ones from around the 1960s to the ’70s, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that they need to be old. Even if they’re a remake, I actually prefer toys that are broken and have been played with by kids. They’re cheaper as well.

You often find that Japanese soft vinyl figures from the 1960s have the name of the child who owned them written on the bottom of the foot. This is because monster figures were so popular, and most parents wrote down their kids’ names on the back of their feet so that they wouldn’t get mixed up with the same toys that belong to other kids. Although their vintage value diminishes, I personally love toys that have various scratches and bear traces of these kinds of things. These kids had played with these toys to their heart’s content back in the ’60s, and now, 60 years later, I’m playing with them! Don’t you think that’s interesting? That’s why, on the back of my works, I write my name, Haroshi, in hiragana.

What’s incredibly appealing to me is such craftsmanship and the heritage of the toys, all these things you combine into your work. How do you think this connects to your life in skateboarding? It's like you have made skating the root of your art, and all these fascinating ideas emerge. This passing of history, too, is a really fascinating part of it.

If you took skateboarding away from me, you get left with nothing. Everything, including my relationship with friends, as well as my work, has developed through skateboarding, and my first encounter with the work of artists was through the graphics on skateboards. The most important thing I learned from skateboarding is that so long as you keep pursuing something, there will always come a day when you’ll be able to do it. I suppose the other thing I learned is that we are all fundamentally free. I’ve been carving out of skateboards for over 15 years now, but the first work I made was really quite bad. The worst thing about it, though, is that I didn’t realize how bad it was, and I had felt moved by how cool I thought it was [laughs]. So that’s where I essentially started, and since then, I have worked my way through until today. That’s what I think learning is about. No matter how clumsy it may look, you feel over the moon when you manage to do your first ollie. So yes, I learned all the important things I need to know from skateboarding.

This may sound weird, but when did you begin to feel like your art career became a real focus? Like, when did it turn into something that you knew you could focus on all the time?

I suppose I essentially became an artist when people started referring to me as one. I have been making things since I was a child. When I make something now, it’s referred to as art, but things I used to make as a child weren’t considered so. I think that’s the only difference there is. In that sense, you could say we are all fundamentally artists.

You probably get asked this all the time, but when was the first time you ever created a piece of art from recycled skate decks?

When I was about 20 years old, I made a shelf on which to display a flower vase. I’d basically just made a hole in the deck, so it was pretty substandard. For a while, I forgot about this piece, and then, when I was about 25, I decided that I wanted to do something new. Not working under someone else, but completely on my own. It was at that time that my wife saw the stack of skateboard decks in the corner of my room and suggested that I should make something out of them. That was really the start of it all, and now it’s been over 15 years!

So, okay, going back to even just a few years ago, your work was focused on both creating a mix of skateboard objects, graphics and pop culture iconography. Now, looking at your studio, I see all these toy recreations. Can you talk a little bit about this transition, and how much you enjoy finding the toy figures, as well as the detailed and delicate work that goes into that?

Skateboards are ridden until they’re completely worn out, and in the end, are destined to be discarded. This is the same case for most of the toys. Since I love fixing things, and, as an adult, I’ve only collected broken things, I thought the way they were broken looked very cool. For me, it’s the same with skateboards, in that I prefer decks with lots of scratches and stickers on them, rather than seeing brand new ones displayed on a wall. I believe that this is, indeed, our reality. We skateboarders have the mind of a skateboarder until we die, and this is why it didn’t feel at all out of the ordinary to fix toys using skateboards. It is more or less the same thing.

I digress a bit, but the real reason behind me sculpting various things out of skateboard decks is because I simply wanted to improve my skills, you know, since I really wasn’t that good at it. That’s why it was all part of a training process to sculpt into worn out shoes to their very limits, in search of a realistic form of expression, as well as modeling other things like hands, feet, and faces. That being said, after ten years or so, I had, to some extent, become good at this kind of work. I think I then realized that the essence of what I really wanted to express was not within the context of pursuing this skill. I thought that my works felt more lively and vibrant when I sculpted freely out of a block without any preliminary plans or sketches. This is how I came to create the GUZO series. The toy series where I work with monster figures and such, more freely explores the ideas I considered in the GUZO series. Before then, I felt really caught up with the notion that I needed to make everything out of skateboard decks. I realized that I had become a slave to the skateboard! I want people to think that my works are cute, and I want them to laugh if they see that they look weird or funny. Right now, I just find great fun in making work. I’m really glad that I’ve continued to pursue making work for a long time over the years.

What do you enjoy about working on such a micro scale, as opposed to the massive sculpture you made in Osaka?

It had been a dream of mine to make something on a large scale. At the same time, however, I feel that I’m able to best demonstrate my abilities when working within the size of a skateboard. When working on a large piece, it’s necessary to have an assistant, but with a small work, you can do everything on your own from the very start to the finish. It allows you to enjoy a time of your own.

Haroshi had a sold-out booth with NANZUKA at Art Basel, Miami Beach, 2018.