Grace Weaver

The Big Picture

Interview by Evan Pricco // Portrait by Eric Degenhardt

Every few years it seems, a critic declares that painting is back (!). And then, of course, painting is back! But seriously, right now, in NYC, there has been a renaissance of sorts in the figurative painting world, one that sees more and more under-30 fine artists finding refreshing and re-invigorating ways to paint on canvas. Seeing Brooklyn-based painter Grace Weaver’s solo show at Soy Capitán Gallery in Berlin in 2017 recalled all the reasons I love figurative portrait painting. In the ways that Joan Brown, Jacob Lawrence or Will Barnet’s portraits represented time-capsules of 20th century America, Grace Weaver’s works provide a discerning glimpse into 21st century life while maintaining the sensibilities of the classic American painter. I visited Grace a few times in Brooklyn over the past year as she moved studios. I observed her practice on surprisingly large canvases, and learned how she has evolved as a painter, readying for her upcoming breakout exhibition at James Cohan Gallery in NYC in the Fall of 2018.

Evan Pricco: I can't remember exactly what it was you were studying at university before art, but I know it was something that surprised me but seemed complimentary with your talent for drawing and painting. What was it, again?

Grace Weaver: As an undergrad, I was studying Wildlife Biology at the University of Vermont. I really thought I would be a naturalist as a little kid and then, at some point, that grew into wanting to be a researcher.

I’ve always been drawn to the idea of having a research project… a big endeavor that I could undertake on my own, gathering information from all over the place and synthesizing something, some new theory. I think that’s why biology appealed to me.

What made you switch?

I took an introductory painting class as a sophomore that kind of changed my life. It was with a super smart, young professor at UVM named Steve Budington. That was my first exposure to contemporary art, and everything was embarrassingly new to me. I remember watching a documentary about Walton Ford, and seeing him dig through museum archives to collect source material for his paintings. I started to realize that art could be a big, highly personalized research project. Art, however, has the advantage that the end-product is legible to almost anyone, which differentiates it from the work of a scientist in a specialized field. That combination of personal rigor and accessibility was what made me want to become an artist. It was my introduction to painting, but my time in the MFA program at VCU a few years later was just as formative. The faculty there was stellar—Arnold Kemp, Holly Morrison, Gregory Volk, Richard Roth—but it was the other grad students that really pushed me to be as ambitious and thoughtful as I could be.

I was thinking about this more after I first met you, noting that your work reminded me of some classic European illustrations, and I started to do some research. There was this era of 1920s, probably more of the 1930s, where I think your work seems to fit. I don't mean subject matter so much, but choice of color. Where do you think you found such color choices?

When I started painting—like so many other painters—I found my way to color through other artists’ work. For me, that definitely included early 20th century European painting. As you try to solve color problems in a painting, you can often find the answer in a Matisse, a Bonnard or a Vuillard. Their use of color just reached a height that I don’t think has since been met. The Fauvists and the Nabis painters are still very much a part of the DNA of my work.

Recently, I’ve become obsessed with the possibility for color to say something about this precise cultural moment. More and more, I’m trying to expand the sources from which I steal color and put it into the paintings. For example, I’ve always loved when a woman with a serious spray-tan (the kind that verges on orange) uses a super pale, baby pink lipstick. That color combination is kind of fascinating in how it treads the line between pretty and grotesque. It’s so temporally specific, evidence of a very 21st century approach to color.

You don’t have to look a lot further from the idea of “millennial pink” to see how much one color can say about a generation and a moment in time. Millennial pink is a muddy and uncertain color, cute without being juvenile, neutral without being serious. We’re living in a strange moment, color-wise. If you walk into any mid-level clothing store—a Zara or an H&M—there are so many odd quaternary colors on display—dusty lilac, dirty olive, rusty orange. We’re definitely not living in a primary-colored moment. Color has the potential to connect both to the distant past and to the current moment.

Do you have a favorite color at the moment?

I have a kind of unreasonable attraction to pink. My favorite color, if I had to choose, is probably a medium pink, as artificial as possible. Golden’s Medium Magenta is pretty close to perfect. I also love Holbein’s Brilliant Pink.

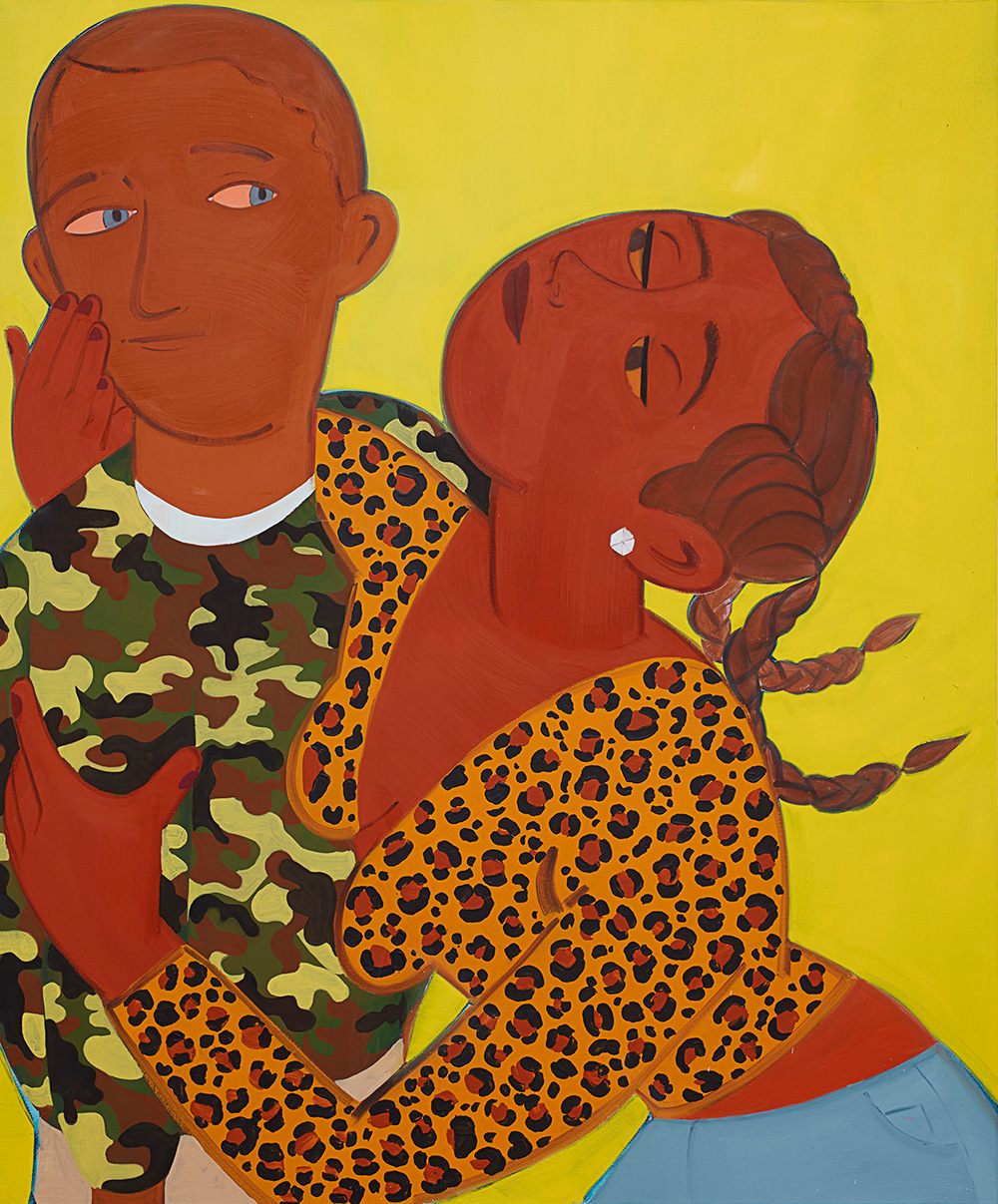

Variations of red, orange and pink have always held so much appeal to me. I think it’s because of their proximity to flesh tones; they come so viscerally close to flesh without being naturalistic. In a dumb way, literal warm colors are a way to make a painting as metaphorically warm as possible. I want the paintings to be accessible, and even attractive and inviting.

Do you have a favorite era of art?

I love Mannerism for its utter abandonment of anatomy. I love the perverse cuteness of Rococo. I love Indian and Persian miniatures for their calligraphic line and idiosyncratic color. Right now I’m obsessed with these folk paintings from Bengal, India, called Kalighat paintings. They have this pared-down elegant brushwork; everything is on the surface.

For similar reasons, I love the Chicago Imagists in general, and Christina Ramberg in particular. Her approach to mark-making is so specific, you really feel the distinction between flesh and hair and fabric based on how she applies paint.

My big painting hero, though, will always be Alex Katz. He has developed a way of painting in which the figure is almost secondary to muscular brushwork and stylization. He’s kind of the big one for me, the ideal that I’m always chasing.

If I called you a contemporary throwback, what do you say to that? No? Yes?

I guess it depends what you mean by “contemporary throwback,” haha! I don’t think any artist would want to be compared to an Elvis impersonator for instance, someone who is slavishly recreating artworks of the past and for the past. But painting is a medium with such a long history that anytime you pick up a paintbrush, you’re inherently connecting to centuries and centuries of painters that have come before you.

Whether it is through resonances in color or form or subject, I do hope that there is some connection between my work and the past. I think that painting’s real struggle is to figure out how a centuries-old medium can say something about the current moment. The truly great artists hold those two poles in balance.

Another terrific painting professor of mine at UVM, Frank Owen, would sometimes say, “Art history isn’t linear! It loops back on itself and leaves openings where you can jump back in!” I love that idea. I hope there is a way to weave together elements from both the contemporary world and the history of painting and arrive at something new. It’s something I think about every day.

I know you show up in your drawings and paintings, but who are the other people in your works?

All painting contains some degree of self-portraiture, especially in the case of figurative painting. That’s how I see the individual female figures in my work. They’re usually stand-ins or proxies for me, but on a psychological rather than a visual level. “Emotional self-portraits” is maybe the best way to describe their relationship to me.

The other figures in the paintings are just as imaginary, and the male characters are often invented as foils to a female counterpart. Certain “types” definitely recur—the absent-minded boyfriend, the eye-rolling sister, the good-natured dad—but they are not so much portraits of real people as they are psychological building blocks, inserted as necessary to complement existing characters. I suppose I am more invested in the relationships between characters than in the individuals themselves.

Scale in your work is important, and I think it really does allow you to have a lot of freedom in terms of creating a scene and exploring color. What do you like about working with bigger canvases?

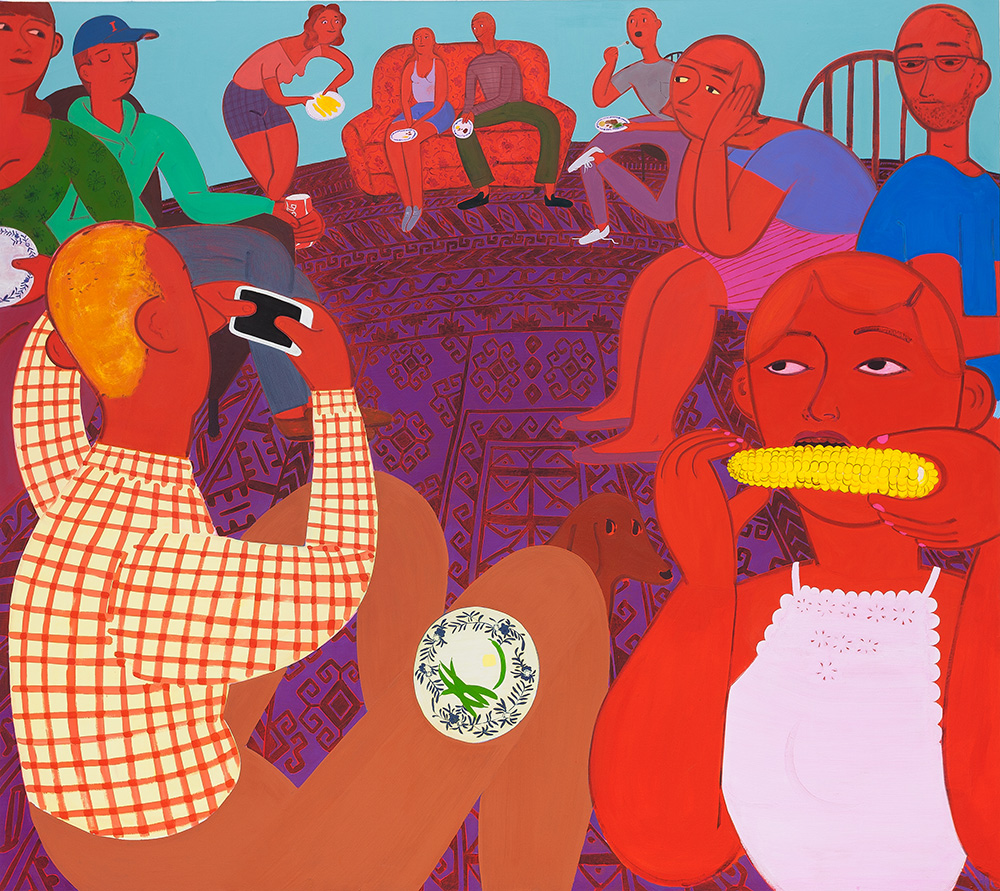

I love working with the biggest canvasses that I can. So much of what is important to me is gesture—dramatic brushstrokes and big shapes. I find that’s only really possible when the canvas is the size of my body or bigger. Some of the paintings for this show are 89 by 95 inches, which is the maximum size that we can fit out the studio door.

The paintings need to be as big as they are to have an impact on a physical level. Color depends so much on quantity. Even if the paintings have a politeness to the subject matter or a prettiness to the color, I want them to be confrontational in some way. Scale is one way to do that.

I really like something you said, something along the lines of painting for other painters, or these little details that you feel other painters see in your work, things that you notice in other artist's work. Can you elaborate? Do you have painters that you find you really relate to in that way?

I think a lot of the best painting is done with another painter in mind. It’s like that quote from Heidegger that, “one can learn to ski only on the slopes and for the slopes.” The thing done for the sake of the thing.

There is so much good painting out there right now. A few artists come to mind as being especially generous with the painterly information they reveal—painters like Trudy Benson, Katherine Bernhardt, Patricia Treib, Keltie Ferris, Charline von Heyl, Amy Sillman and Mary Heilmann. I don’t mean that they are all straight-forward painters, but that they leave breadcrumbs for the viewer to find their way into how the painting was made. That lets the viewer do a sort of mental reverse-engineering. I find that to be the most rewarding kind of painting to look at and it’s something I (very humbly) aspire to.

It’s an idea that goes back to my art history studies as an undergrad. I worked with an Art History professor at UVM named John Seyller, who is an expert in Indian miniature painting and just a ferociously intelligent person. His challenge for us was always to identify the artist’s hand in a painting. He would drill us on attributions, differentiating for instance between two brothers from the same family of Pahari painters from 18th century India: “Is this Nain Sukh or Manaku? Or (their father) Pandit Seu?” Over and over. In a way, his emphasis on close looking and the search for the artist’s hand taught me how to see. The pleasure is in those details.

You showed me a series of photo documentations of your newest works, and what stands out is how much evolution and underpainting is involved in each. Characters come and re-emerge, action shifts, movements totally change as well. Has this always been a feature in your work? Do you create inner dialogues about what the characters in your work are saying to each other?

In the earliest stages of a painting, I spend a lot of time working in one or two colors, figuring out the composition. I start out more in the mode of an abstract painter, concerned mostly about the geometry and rhythm of the painting. It’s kind of like piecing together a puzzle, working through trial and error until all of the shapes come together.

That happens before I’m even considering facial expressions or clothing or relationships. The individual figures arise as the residue of the activity of painting. I’ll need a big swath of blue and that requires a girl in the background to have an enormous blue-jeaned butt, for instance. I like when the figures end up surprising me, when my mind is more caught up with issues of color and form.

What do you like about seeing all these changes in one painting, even when you’re learning or being self critical?

My fiancée, Eric, is an amazing photographer and helps me out in the studio full time. He’s constantly taking photos, capturing all of the awkward stages as the paintings evolve. It helps me so much to look back through those photos and see what each painting has gone through.

There is always the experience of looking back and thinking “Damn, that was better the first time.” But painting is a bit like a choreographed dance: maybe you have a particular move right on the first try, but all of the moves have to fit together in sequence. So, when things go wrong, I usually wipe down the whole painting and start from scratch. The goal, in the end, is for the painting to congeal into one continuous surface, one flat image.

How important to your process are all the drawings that you make? You work in a large format, and you have all these drawings that you reference, so where do those end up?

One of the best feelings in the world is something that we all have as little kids. You know, that feeling of doodling with crayons or markers without an endpoint in mind and inventing something that makes you laugh out of sheer surprise. Drawing is a way to tap into that feeling, the feeling of invention.

Drawing is also the most direct sort of image-making, and a way to generate tons of ideas. There is no reason not to make a drawing because it’s so low stakes. That allows me to entertain the tiniest and dumbest of ideas, whether it’s someone painting her toenails or buying bodega candy or fixing her bra strap. Sometimes, though, one of these “dumb” ideas will have a magnetism or a poignancy that demands to become a painting.

Can you talk about your new show, because in the three large paintings that I saw, there is this really beautiful portrayal of mundane daily acts. You have been really tuning into these little acts in your paintings, and it feels like a very elegant look into some personal daily rituals. What have you been focusing on?

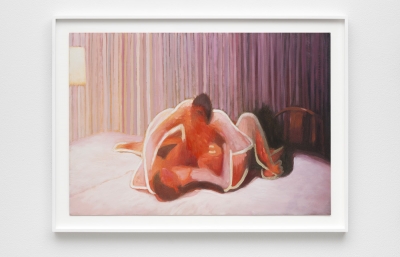

Yes, the subjects in the most recent paintings could not get more mundane. There is a girl applying makeup, a girl preparing a sandwich, a girl washing her face. To use a very 2018 term, they are all acts of “self-care.” They are also acts of self-improvement, re-invention and performed “thriving.” I’m drawn to these moments for their vulnerability, their precariousness. Just as these girls are trying to put themselves together, the painted surface is trying (also self-consciously) to put itself together. I think there is a funny resonance between an individual girl striving awkwardly towards some beauty ideal, and the act of painting, which is always alternately striving towards beauty: faltering, flailing, and reconsidering itself.

This is your first solo show in NYC in awhile, and it’s a big show at James Cohan. What are you excited about in terms of showing back at home, and does an extra set of expectations come with it?

This is my first solo show with James Cohan and it’s a huge honor to be working alongside such smart, kind, incredible people. I feel really lucky to be showing with them.

In general, there’s so much great painting happening right now in New York. Solo shows are always a little nerve-wracking, but I’m just excited to be a part of it all.

Grace Weaver’s new solo show, BEST LIFE, will be on view at James Cohan Gallery in NYC from September 14—October 28, 2018.