Andy Warhol

From A to B and Back Again

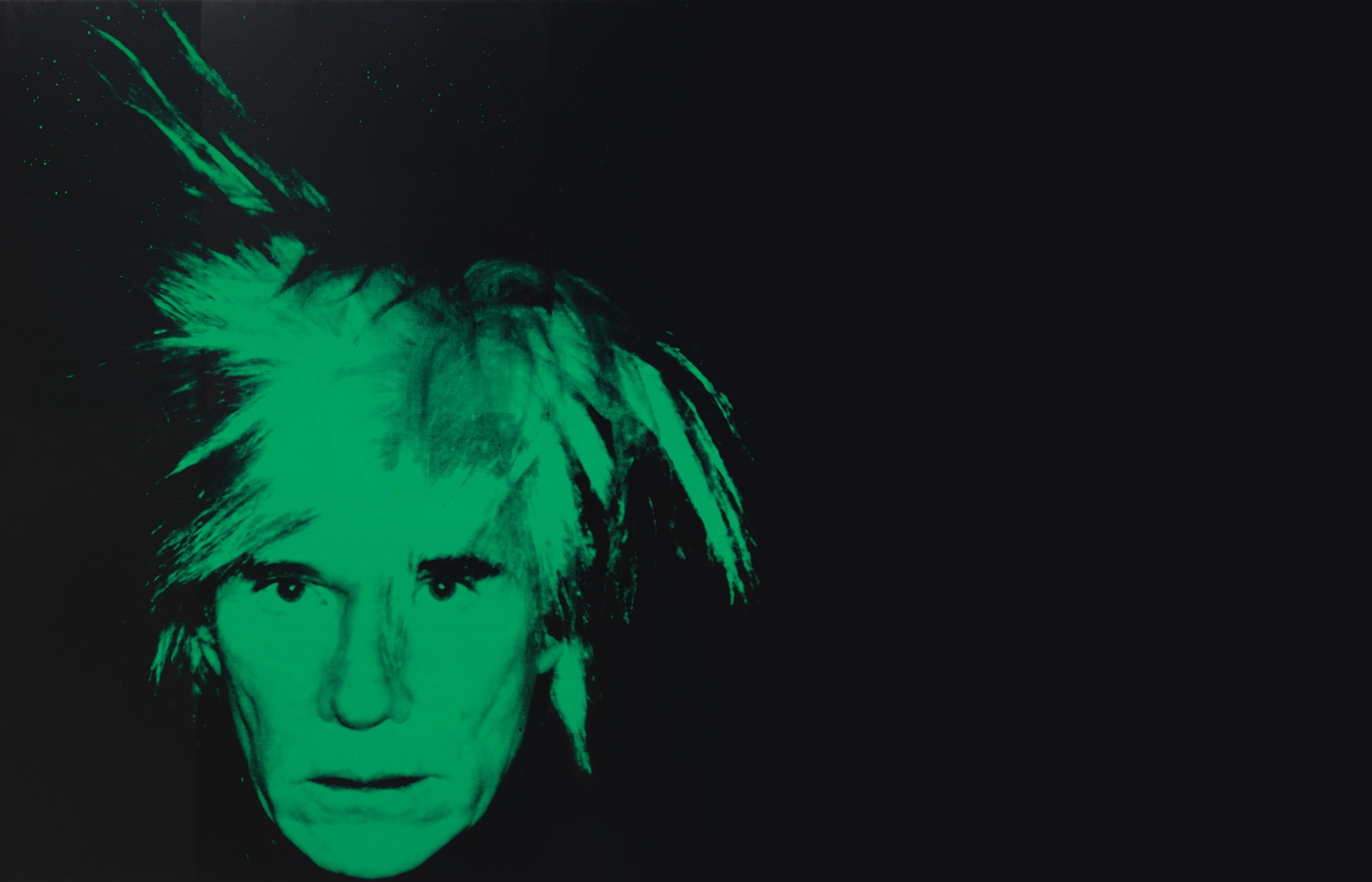

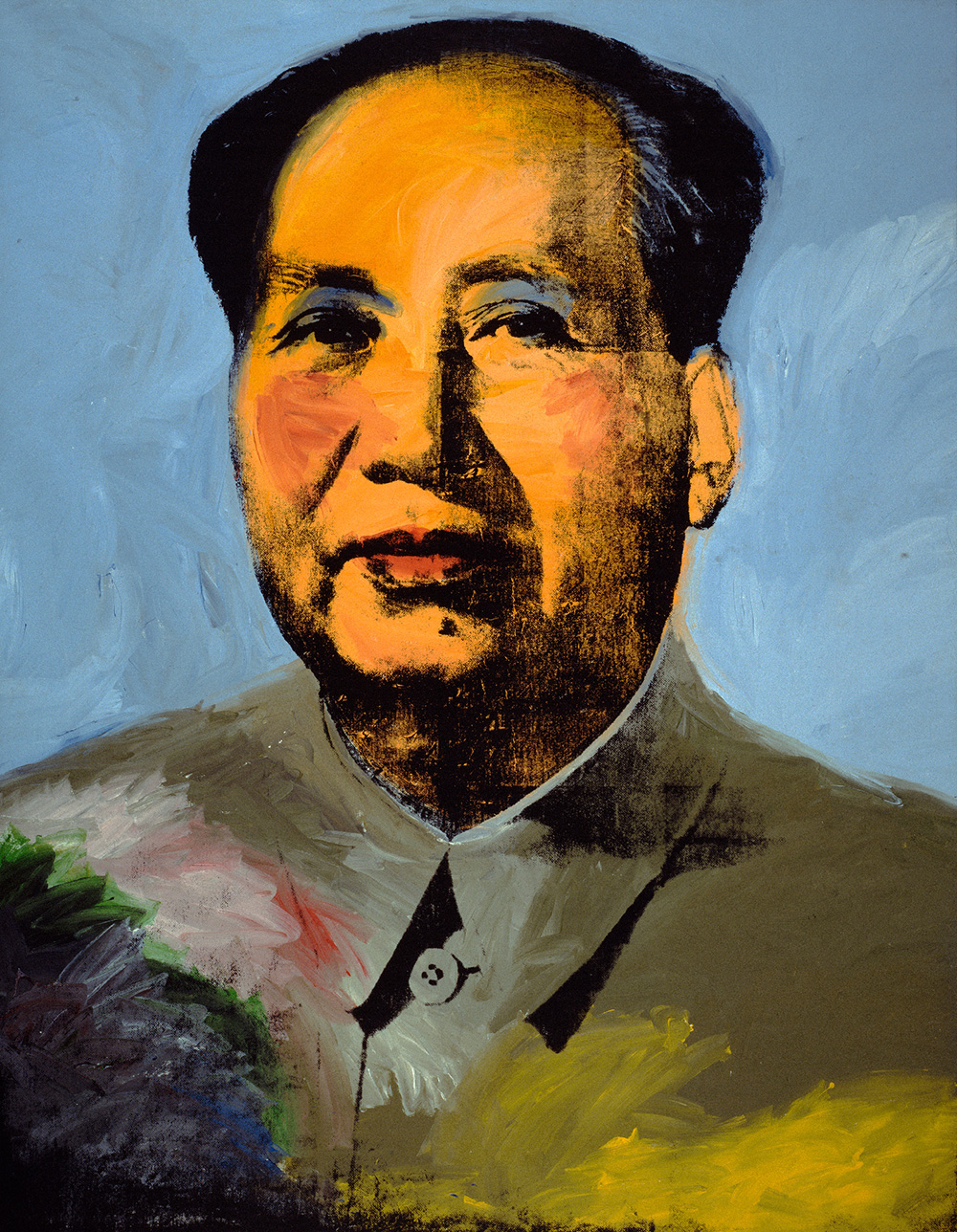

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by Andy Warhol

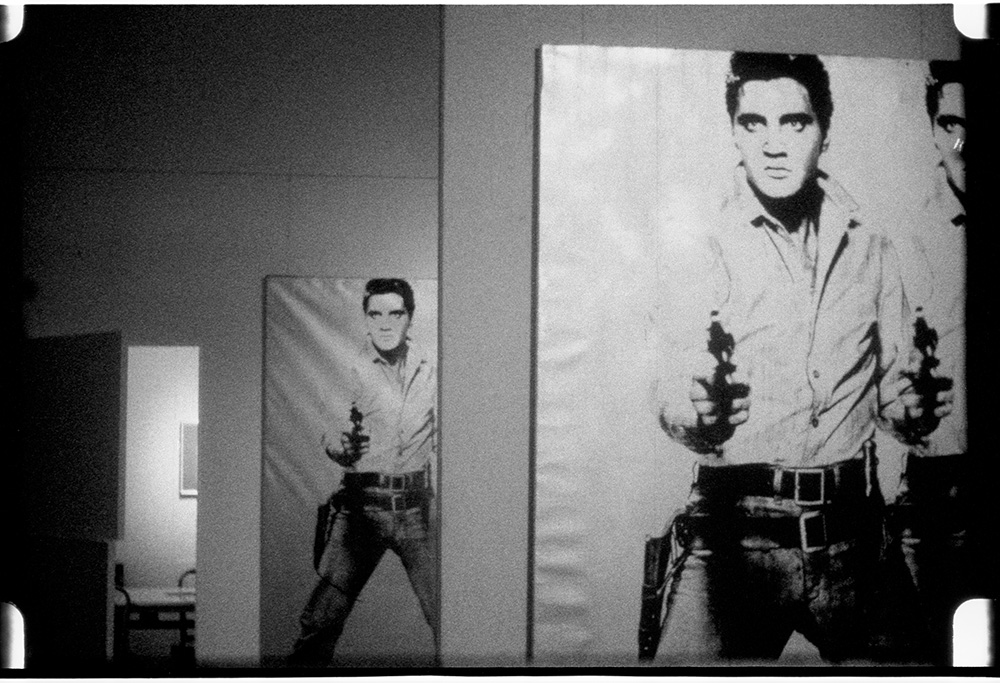

“I don’t think art should be only for the select few. I’m not the High Priest of Pop Art, that is, Popular art, I’m just one of the workers in it.” While it might be hyperbole to characterize a conversation with Andy Warhol as revealing, his 1966 interview with Gretchen Berg is considered the most expansive. In typical Warhol plain-speak, those words she extracted explain why his name is a universal twenty-first century art reference and cultural bellwether. Campbell’s soup cans, triple Elvises and The Factory spring to mind, and his methods of collaboration and production still inspire debate.

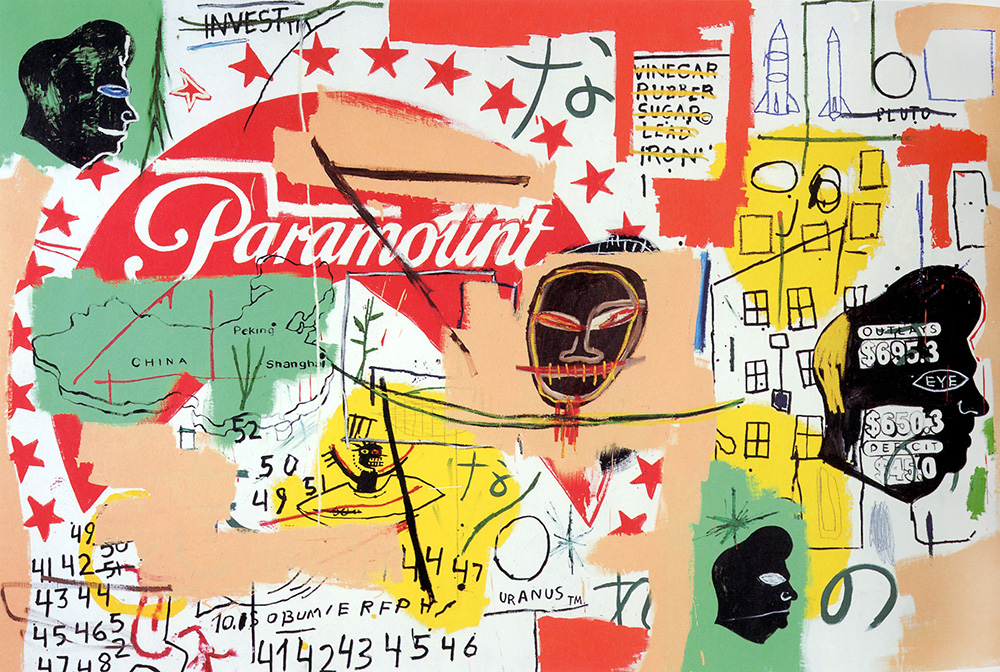

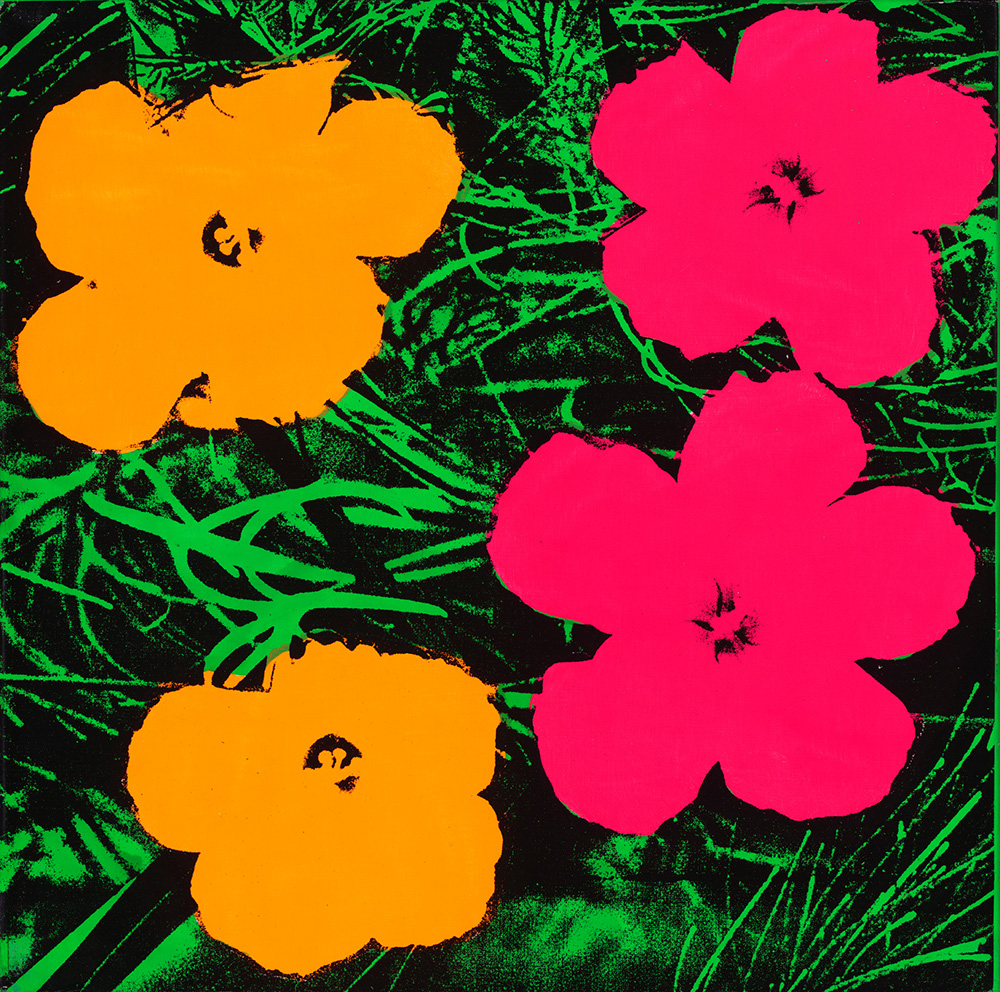

On November 12, 2018, New York’s Whitney Museum will open the encyclopedic Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again and, of course, display the greatest hits, in addition to cinema and early commercial illustrations, not to mention a gallery of the flower paintings mounted on his cow wallpaper, and a rare chance to see pungent later works like the hammer and sickles, skulls, and Basquiat and Haring collaborations. Warhol expert and senior Curator Donna De Salvo met me for coffee at the beautiful new Whitney and spoke with depth and affection about the Pioneer from Pittsburgh.

Gwynned Vitello: So, you’re the expert! How long have you been studying Warhol?

Donna de Salvo: Well, you know, I met Warhol in very late 1985 when I worked for the Dia Art Foundation. I actually worked with him on an exhibition of prints from their collection, so I had this prior interest, having studied so many incredible works he’d made. The Dia collection had many very early things from the 1950s and early ’60s, and more particularly, the works that he had made prior to making the silk screens. So I was interested in where and how he got to this point.

I didn’t realize he was such a talented illustrator.

He was a terrific craftsman, I mean, he had a really incredible hand for drawing and observation of people, something you wouldn’t automatically know know when you look at the silk screens.

Apart from The Factory, I think that’s what most folks connect with his name.

He didn’t allow any of that other work out into the world for the most part. People knew the silk screens were really revolutionary. I mean, to make painting in that sort of way was kind of incredible. I was lucky to see some of these early things and that piqued my interest. I was trying to figure out what was going on during this 1950s period and what was he doing while working for art directors and fashion magazines. That became very important in understanding the foundation of a guy whose work was so much about looking at advertising and desire, all of these sorts of things, about style and figuring out what the audience wants: to push the analogy, about pushing a product. It was the great rise of American advertising, so I was really intent on understanding his process.

Of course, this what you do with any artist’s first works, although many don’t like talking about their early stuff. I don’t think they like talking about the things they were making just before things really came together for them. A lot of artists only really like talking about what they’re working on at the moment.

Are there many of his drawings as a young artist, say, dating before art school? Where are they?

Within the museum are some of his childhood drawings, and he did show when he came to New York in 1949. That was a show of drawings of Truman Capote’s writings, which was probably because he wanted to meet Capote. But, it’s really very obvious that Warhol made those drawings; the quality of the line is just so beautiful. In talking to him, I got really interested in the work before the silk screen. He was still hand painting, like the Coca-Cola bottle, with all these dripping marks on it. That’s when I did some interviews with him, and it was a good moment because he was also interested in the younger generation of artists like Basquiat and Haring. I, of course, was a younger person, so I think that I was picked at the right moment.

And he was also a product of that moment.

I think also, in a lot of ways, people don’t realize that, in the ’80s, when we met, he was not really seen as this major figure anymore. A lot of his work was just being shown in Europe. It wasn’t as if there was real cynicism about him, but the perception was that his ’60s work was considered his best. They didn’t know what to do with the Rorschach and Last Suppers, for example.

I know you studied his work, but wasn’t he a tough interview?

I did make a kind of rookie mistake the first time, and it just didn’t work out. He was quiet and I kept filling in the gaps, talking and asking dumb questions, the kind where you’re looking at things in a theoretical way. But he was very down to earth. In the second interview, I realized, “Okay, just stop and ask a question, have the awkward silence.” And then he really would talk, you know.

One of the advantages I had was working for the Dia Foundation, which was a big supporter, so it created a bond, and perhaps made him feel more comfortable and he could trust me. In fact, as we talked, it started to seem like gossiping, so I turned off the tape recorder. People either love or hate him, he’s the guy with the funny wig, he’s the freak, or he’s this or that. But I had respect for him and always addressed him as an artist.

Clearly, I had some preconceptions before researching Warhol, and, as I alluded, didn’t know of the range of his skills.

Most don’t, and at that time, in particular, to be seen as a commercial artist was looked down upon by the other artists. It’s been written that when Johns and Rauschenberg did window displays, they worked under a pseudonym, whereas Warhol always used his name. I think part of Warhol’s genius was the willingness to embrace that, so he set foot in all of these worlds. He loved art and he wanted to be seen as a serious artist, but he also had an understanding and respect for the people who worked within the realm of commercial art. In preparation for an exhibit of his early work, Success is a Job in New York, among others, I interviewed Tina Fredericks, art director at Glamour, Lou Dorfsman, head of graphics at CBS, and Steve Frankfurt, who, in the ’50s, was VP at Young & Rubicam, all people who had hired Warhol. In meeting them, I realized that they were total visual thinkers who could craft an image so that it would communicate. These folks were really knowledgeable about the history of art. Warhol admired them, and they were attracted to something about him and his work. I think he learned in those campaigns and sharpened his intuitive “smarts.” Keep in mind that Warhol came to New York in 1949, right out of Carnegie, the same year Life Magazine did a spread on Jackson Pollack, aka Jack the Ripper, asking if he was America’s greatest artist. That’s when Warhol came.

Will there be any Warhols from that period?

Yes, and you see the subject matter that he is really interested in, and you see it is very light, children dancing. Plus these boys kissing; it’s a very different kind of subject matter. I think that the ’50s were important because you see a Warhol that you don’t see again. But he’s still there and the choices that he makes, whether it’s Marilyn or Elvis Presley, any of those choices in the ’60s function on so many different levels. They appeal to multiple different audiences, and they’re very coded in that gay men got certain parts of the work, and the straight men or women would find appeal in certain ways. That’s where I think he was such a genius in that he always chose things that were very topical in the news.

He was really aware what would push buttons, but he was also in the right place at the right time, correct?

He definitely had that awareness, which you can see in his diaries or in his Popism book. He was really interested in Elizabeth Taylor, really obsessed with her. When Marilyn Monroe died, he had to do that tribute; she was so much in the news. Some of the paintings honed in on a particular tragedy, even tabloid news.

But his choices were deeper than that.

They had import, and he was attracted to them in many ways. He loved gossip, he loved all of that stuff. But it’s the smarts of picking a subject that also reflects something in the culture. A great example is when he does the electric chair. There was a lot of discussion in the U.S. at that time about the death penalty, so why choose the electric chair? It wasn’t an arbitrary choice; his choices where never arbitrary. They’re rooted in the history of art, rooted in the history of popular culture. And with any artist, you never really know the intent. On some level, there was something that had appealed to him as well as art. Great art, to me, is art that you can never really figure it out.

That chair was something I thought about with horrible fascination as a kid, imagining that something I sat on could kill me!

So, here is this post-war America, everywhere is this perception of optimism. The U.S. is in this real boom and then Warhol chooses the image of the electric chair, something so, so barbaric. I think this is where Warhol got to the dark side of the U.S., which we see is more with us now than ever before.

His pictures of Liz Taylor and Marilyn Monroe are glamorous, but yes, very dark.

Exactly, and that’s why you can’t pick out any one of them on their own. Raised as a practicing Catholic, he grew up looking at the icons in the church, usually adorned in gold, and he understood just how to crop that image. When you look at the image of the Marilyn Monroe painting, notice the cropping. It’s an image from the ’50s actually, of her in a film still from Niagara Falls. But he crops it really tightly to get down to the important visual information, so it has the greatest impact.

I grew up Catholic, and I remember the holy cards as little icons. They were beautiful but just on the edge of being so frightening, always enhanced with drippings of blood and a storyline of torture.

I did too, and as a Catholic, you understand that use of imagery. Many of the other religions were a lot more modest and restrained. Then you have Warhol looking at history, even in his portrait making. He had this system at The Factory, so that, like the Renaissance, people were working as assistants.

For which he received a lot of criticism.

What he was doing was so different. Put into context what was happening in the ’50s and ’60s, and you look at a Nauman or Rothko, who were speaking of the individual and transcendence. Then, along comes Warhol. I remember this article written by Max Kozloff talking about pop artists, whom he called the “new vulgarians.” But by the late ’50s, Abstract Expressionism was in its second and third generation. Every new generation has to both honor and kill.

Warhol had an understanding of what constitutes originality, and that also came with process. The step he took was not to just make an image look mechanically produced, but to actually mechanically reproduce it! Once you do that, you move forward and go on to something more mediated. Some people argued he that he killed painting, others say he advanced it. But he takes the subject and marries, not only the subject, but the way it actually lives in the world. You know all these images live in reproduction; they’re all fantasy, all illusion, all constructions.

In some ways, he was challenging that romantic notion of artists in America that the ’50s were so much about. Many perceived it as completely separate from the commercial art, very high-minded in a yes-or-no kind of way. Warhol put forward a proposal of how you can be an artist in American culture. Think of the people who came after, like Koons or Murakami. Those artists created amazing enterprises. Warhol put something forward and a lot of people hated him for that.

Well, you can’t discount his youth as the child of immigrants, growing up with an illness, watching movies from his sickbed. He even called one of his films Poor Little Rich Girl from the depression-era Shirley Temple movie of the same name.

Think of him as a young gay kid growing up in Pittsburgh. I moved to New York because I loved Andy Warhol, and I think New York is a place to invent or reinvent yourself. So he’s part of a long line of creatives—but do you ever really leave behind where you came from? Some people never want to reference it. He, in fact, never went back to Pittsburgh, not even after his mother died, his mother to whom he was so close, who came to live with him in New York. I can only speculate that it was very painful for him to go back.

I know he traveled extensively, but somehow, I identify him so much as an American artist.

You always get that in one sense or another because so much referenced would be about, say, Coca-Cola or McDonald’s, the things that are very symbolic of the US and which all became global. He’s still one of the artists that people know. They know Van Gogh, they know Monet, they know Warhol. He still has a popular appeal that few other artists actually have.

Following up on symbols, how did he transition from growing up on glamorous Hollywood movies to making his unscripted, often gritty films?

His films really take apart the Hollywood essence. He looked at that star system which was increasingly coming to an end, and what he did was to make superstars—in films unscripted and improvisational. He was the consummate director in setting these things up and letting the film go. Sometimes he’d walk away. His scripts were improvisational, and as a great social observer, he didn’t force people to do what they do, but was able to create a situation.

He was so busy with so many people and projects, and sort of following up on that, didn’t he say, “the news belongs to everybody”?

He got his ideas from this person and that person, and at the end, was able to execute. It was like crowdsourcing. There’s an absolute communal quality, and he could recognize when something has currency in the culture, like Coca-Cola. The product could have a personality, and it becomes a kind of portrait. Designed by Raymond Loewy, this beautiful bottle is still so symbolic, ubiquitous and still one of the most advertised products in the world.

This is great timing for the show, after midterm elections and during so much class conflict.

Yes, America at war with itself. In one of his narratives, he talks about how everyone has their own fantasy of America, that theoretically, it is a great concept. There is something about the complexity of this amalgam of a country. It’s got dark sides, and some that were more hidden are starting to come to the surface. I feel that there was a sort of love and hate for those objects, even in the ’50s. Of American culture, the critic Holland Cutter wrote that Warhol either celebrated or skewered it. I’m so interested in looking at what his work means today. He had a way of making everything part of his art, it all became part of his art.

Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through March 31, 2019, and then travels to SFMOMA.