A Revolution of the Ordinary

Nuart Aberdeen Captures Our Contemporary Mood

Interview by Evan Pricco // Photography by Ian Cox

When Martyn Reed of the esteemed and renowned Nuart Festival set the theme for this year’s Nuart Aberdeen, “A Revolution of the Ordinary,” I had a feeling of both elation and defeat. And to be honest, I wrote a rather ranting, sort-of-disappointed-in-the-21st-Century-and-all-its-social-revolution-mechanisms essay about what I thought was supposed to be our (the people’s) controlled destiny of how we communicate with each other. Our “ordinary” lives were going to become “extraordinary” through new platforms of communication, public art, and the democratization of critique and gatekeeper cultures. You can read that rant here.

But this is one of the beautiful things about the curation and themes surrounding each Nuart festival, whether in its original home of Stavanger, Norway or now celebrating its second year in Aberdeen, Scotland. The festival is not afraid to look inward, to understand the nuances and flaws in contemporary street art, and develop conversations that both tie street art to the historical interventionist movement, and also critique the prevailing corporatization and gentrification that the movement has fallen victim to over the last ~10 years.

That is where I get stressed out, or perhaps start to get up on the proverbially soapbox. Is Street Art, perhaps the most important art movement of my lifetime, going to lose all of its deviant qualities? Doesn’t its popularity mean that its own ability to democratize the art world has been wildly successful? As Reed wrote in his essay on this year’s festival, “Street Art’s call is to reclaim and broaden the terms ‘Art’ and ‘Artist’, and to remove the shame that those not privileged with an arts education often feel when employing these terms.” To a large extent, this has happened, and it continues to happen. There is a healthy place in our own inward criticism, once we actually get outside and take a walk around.

Another thing I found myself doing often in the lead-up to Nuart Aberdeen was question what I thought of the word “ordinary.” I mean, hell, for the past 15 years or so, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have made it so every single one of us seems so extraordinary that “ordinary” almost feels like an insult. How dare you call my life or my experiences ordinary? I had brunch this morning on a antique wooden table for crying out loud, and shared it with 51 strangers! But Nuart was clever here, placing the word ordinary in the context of hyper-sensitive, perhaps over-educated art history critics who have excluded nearly 99% of all people from enjoying what really is an incredible moment in Art. There is so many good things happening! And not just Banksy or Nuart or JR. I’m talking about Kerry James Marshall, Toyin Odutola, Jonas Wood, Yoshitomo Nara, Laura Owens… Museums and galleries have such great shows right now, but many people have felt like they can’t participate or enjoy the culture because the culture was only made for those who read the right books, go to the right schools, and eat at the right restaurants, inferring that these gatekeepers are right, and the average people are wrong. So, ordinary isn’t so simple: it’s just everyday life. It’s waking up and going to work at 630am. It’s eating your lunch on park bench. It’s going home each night knowing that perhaps you only have a few hours in your weekend to see the Walker Evans show at your local museum. “Ordinary,” in the Nuart Aberdeen sense, is finding ways to bring art into your life that is not dictated by the cultural elite, or as Martyn Reed notes, “A broadening and more inclusive definition of the terms ‘Art’ and ‘Artist’ which breaks down the elitism in visual art culture by challenging the notion that only a select few people with special talents and understanding can participate in its production and only the moneyed and cultural elite should own and define it."

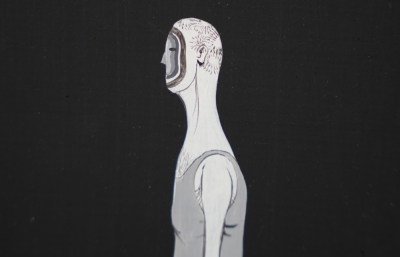

So, The line-up for Nuart Aberdeen included Street Art, Muralism, Wheatpastes, Sign-painting, Politics, Craftivism, good ol’ fashioned subverted advertisements, a broad spectrum of artists from around the world, accompanied by discussions and inclusive conversations about the current mood of contemporary Street Art. The artists featured were Bordalo ii, Hyuro, Carrie Reichardt, Bortusk Leer, Phlegm, Ernest Zacharevic, Dr. D, Ciaran Glöbel and Conzo Throb, Elki, Milu Correch, Snik and Nimi & RH74, all working off the theme of “A Revolution of the Ordinary,” but also integrating their own personal strengths in their respected mediums, with nods to Aberdeen and Scotland as the backdrop. Carrie Reichardt’s amazing tile work channeled the long and illustrious history of famous women in Scotland, with one particular mosaic work proclaiming, “We are the granddaughters … of all of the witches you were never able to burn.” Phlegm’s mural welcomes you into the city center, centered on the history of Aberdeen’s granite mining, while Ciaran Glöbel and Conzo Throb’s sign-painting work demanded a double-take to determine if it was an authentic ad.

Bortusk Leer added color and a bit of playful cartoon-style all around the town, while Zacharevic, Snik, Elki, Milu Correch, Snik and Nimi & RH74 all created murals that stood on their own as new monuments in the city. Bordalo’s recycled-trash-turned-Scottish-unicorn mural drew a crowd at its completion, and I even saw some members of the local police force snapping a few photos while on duty. Dr. D and Hyuro took turns with politically-themed works, Dr. D himself wheatpasting around the city with subversive works that at times caused a bit of a stir. You can’t quite place a fake ad with a Coca-Cola can that reads “Buy the world a God” across from a church, and not exactly go unnoticed. Hyuro’s mural reflected on the enduring and at times contentious relationship between Scotland and England, a work that was both a heartfelt and passionate embrace with the physicality of confrontation. As much as it explored the complexities of a particular relationship, the mural reflects a continuing international mood of bonds being taken to the brink of altercation, but imbued with the necessity for compassion.

I was asked on a few occasions what I thought was the difference between the 2017 and 2018 Aberdeen festivals, and perhaps that was what took me a few days to work out what that difference was. There was a sense of excitement in Aberdeen that was palpable this year, but there was also a bit of confidence from locals to analyze and think about what the works were doing to their city. Not exclusively discussions about art, but conversations on how to better utilize the local creative community once this festival leaves town. The city has strong institutions, including the stalwart Peacock Visual Arts, that only get more emphasized when the annual festival comes to town. That has long been Nuart’s strength: to reinvigorate a discussion about a city, how it’s used, how it can be creatively utilized by its citizenry in a more democratic way. Real community. Real group decisions. If that act is “A Revolution of the Ordinary,” this year’s festival was not only a success, but a continuing blueprint for our daily lives.