A History of Jaz

Franco "JAZ" Fasoli

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by Todd Mazer

Trying to define jazz is fraught and elusive, and so is any attempt to pigeonhole the multimedia artist known as Jaz. Born Franco Fasoli in Buenos Aires, the painter-sculptor-collagist, bred in the tradition of opera, draws and draws from the fusion and confusion of life. We sat down together at the Juxtapoz Clubhouse during Miami Art Week and talked about the beautiful noise.

Gwynned Vitello: I have to admit I was skeptical when I read that you first studied at the Instituto del Teatro Colon. That’s like going to school at the Met or La Scala.

Jaz: I studied at the opera house right after I finished art school. It was like my secondary school, where you go between 12 and 18 years old, and I finished as a ceramicist. Right after that, I got interested in building props and stage design, so I got into the opera house. They have an institute for people to work in different areas of the theater, like music, dance, clothing and stage design, which is what I was interested in. It combined many skills I liked, such as painting and sculpting, but with a particular purpose. I was always interested in the theater because of my family; half of them worked at the Teatro Colon.

My husband’s family was from Argentina, and on one side, the children were named after operas.

My grandparents on my dad’s side worked at the Teatro Colon, one a piano player and one a dancer. Both uncles worked there, one a stage builder and the other, an archivist. My mother’s parents both paint, and they teach graphic design. When I was a kid, I was skilled in art and liked stage design because it was a good combination where I could put many skills in one direction. Then I taught stage design at Teatro Colon after I finished my own studies.

What an opportunity to work in such a gorgeous building, like an inspiration in itself!

It was amazing to work and study there from 2000 to 2008, when they started renovations. And, at the same time, I had a stage design company I had started with other students. For ten years, we did scenography for anything you can imagine: film, theater, parties and advertising. We would build anything you wanted, so it was an incredible ten years for a young man to work with the masters of stage design in Argentina. They embraced me, so it was exciting in terms of knowledge and different ways to work. Learning all those skills helped me create languages for each. So the art background, stage design and graffiti just mixed together—and boom!

Most graffiti artists don’t start out this way. How did your family react?

For me, it was a kind of self-rebellion, a way to clash against my background, a way to escape the heavy tradition. My family was fantastic, and my grandfather became a super fan. When I started to paint graffiti in the ’90s, there wasn’t too much information about it in Buenos Aires, and there wasn’t any danger around it, so I had their full support.

That was then, and…

It’s not like that anymore. Graffiti exploded many years ago, and now the government is everywhere, cleaning it up, giving big tickets, putting up barriers. Now it is really hard, not like when we started and they gave us walls and paint.

Did the ornamental style of Fileteado have an influence on you?

We did grab that emblematic culture for our graffiti and tried to create our own style; it was very naive. At the beginning of the movement, we got all that culture from Buenos Aires and put it in our own style. It was so easy, so cool.

Tell me more about how you started.

With graffiti, I started when I was a student, even before stage design, when I was fourteen or fifteen. I was really into skateboarding, BMX and hip-hop culture. In our city, it was a small scene, but I had my drawing skills and we all knew each other. Graffiti came from outside, especially from Brazil, because of that first generation of artists like Os Gemeos. They came to Buenos Aires because it was close, an empty city and easy to paint. They came, and we saw those crazy yellow things, and started to check the early internet, like Art Crimes and graffiti.art. We tried to understand what it was, and I remember that with my first, I knew to put my name. I would put bands’ names. We started out bad, but we really wanted to find out what it was.

I can’t imagine a more political and artistic place than Argentina, so I am surprised it started somewhere else.

The dictatorship finished in 1983, and I was born in the dictatorship. The ’70s were extremely violent and the streets were dangerous. Painting in the street was nearly impossible. Graffiti you saw in the street was extremely political, but you were risking your life. I remember presenting myself as a graffiti artist and having a conversation with some older artists, one of them an art historian. He said, “What do you know about graffiti, about a group who really risked their lives, and you, just going around tagging?” I realized I had started out in a democracy where everything is chill. I realized how strong it was, working in a public space in those times, and why it started so late.

Also, in Argentina. the hip-hop culture isn’t as big as in other countries. It’s more rock ’n’ roll, even now. In that time, even Chile was much stronger, and it was a connection we made because of the language and proximity.

Then you lived in the Palermo Hollywood neighborhood of Buenos Aires. What was that like?

Again, it was hip hop that influenced me. It was a very small district, and we knew each other so well. The first hip hop jams were super small, super ghetto, with only one place to party. Everyone was really connected, and for me, I felt a good vibe. We had a good relationship with all the artists and the scene, Then it exploded and became a different situation.

You were into hip hop, but at the time, you were painting classical musicians.

I was still working in stage design, and my next steps were to go beyond graffiti and use different materials. 2003-04 was when I decided to use the shittiest materials I could find, and that was, like, the real beginning.

Maybe that’s partly a result of your background in set building.

I always tried to stay with the concept. When you work in a public space, you should keep it like that, push that aspect. So I started to work with materials I would find in the walls or on the street, the least I could use and the cheapest. The spray can materials became super professional and specific, so I decided to use the shittiest stuff I could find. I wanted to go back, to find another language that fits better with a public space. In the beginning, I tried to use a simple style, more typical, like Fileteado, and realized I could use my chosen materials to show my relationship with my city. Gradually, I moved away from the streets and into the studio, but I used the mentality from the streets to have a dialogue with the pubic space.

Did you have any ideas that just didn’t cut it, any materials that absolutely did not work?

Almost everything didn’t work! I liked the fact that they had an ephemeral feel. Tar was one of the best because it was very cheap and disappeared! It gives a chance to work in a pictorial way. I remember going to paint with a bucket of tar for maybe two dollars. I would go to the gas station, grab the cheapest gas and dissolve the tar with it. I did a lot of pieces with just those two materials, including many big walls. With the sun and environment, the piece disappeared little by little. I would use dust from the ground, brick, a lot of coal, also a lot of limestone because, in Argentina, the advertising was done with limestone. There is a whole culture around the people who do political pieces with it, and I did a project with them. What they do is illegal, so they work at night, same as with graffiti. I went to their studio and did some pieces in that style. Little by little, the materials took over my work. That gave me the mood to work with paper, and now I’m also working with bronze.

And when you work in sculpture, you fabricate the whole piece, don’t you?

For me, I have no problem with other people’s methods. I understand how contemporary art works, but I’m an artist who really needs to be involved in the process. That’s the main thing driving me. I like to draw from my palette of skills and mix them to see if I can find my own language using them. My friend from Italy, 2501, asked me to make a sculpture with a machine he had. I had it in mind to work with bronze for a long time.

Which led to you moving to Spain.

I moved to Barcelona particularly for love. My girlfriend lives there. I had tried to work with bronze in Argentina, but it was too expensive. I asked some friends in Europe and the States, and especially Zio Ziegler from San Francisco, who gave me a hand and advised me. I found a place in Barcelona, and that opened another part of my brain. I continued to work in sculpture with other materials, fabric, polyurethane and ceramics, and had a dialogue with those materials. That gave me another problem in my mind!

But I know you’re still painting.

I’m doing more collage than anything, but still painting and sculpting a lot. Before, my work was divided between inside and outside. Now it’s more divided between 2D and 3D; so again, I’m excited about all the possibilities.

What’s the difference between working in South America and Europe? Of course, Barcelona is now a whole other story.

Before, Barcelona felt divided, but now it’s divided in a bad way. There are acts of violence between the ones who are independent and the ones who are extremely nationalistic isolationists. While it’s still a developed European city with the good vibe of Barcelona, it’s even more intense because it’s small and concentrated. There is the good vibe of tourists, but also police helicopters hovering overhead.

So you went from Argentina to this?

Ha, every time I put up a video of the riots, all my friends from Argentina say, “You went all the way there to see the same thing?!” But I like struggle. If you ask anyone from Argentina, it’s love and hate at the same time. Now that I live in Spain, I would miss that energy at some point.

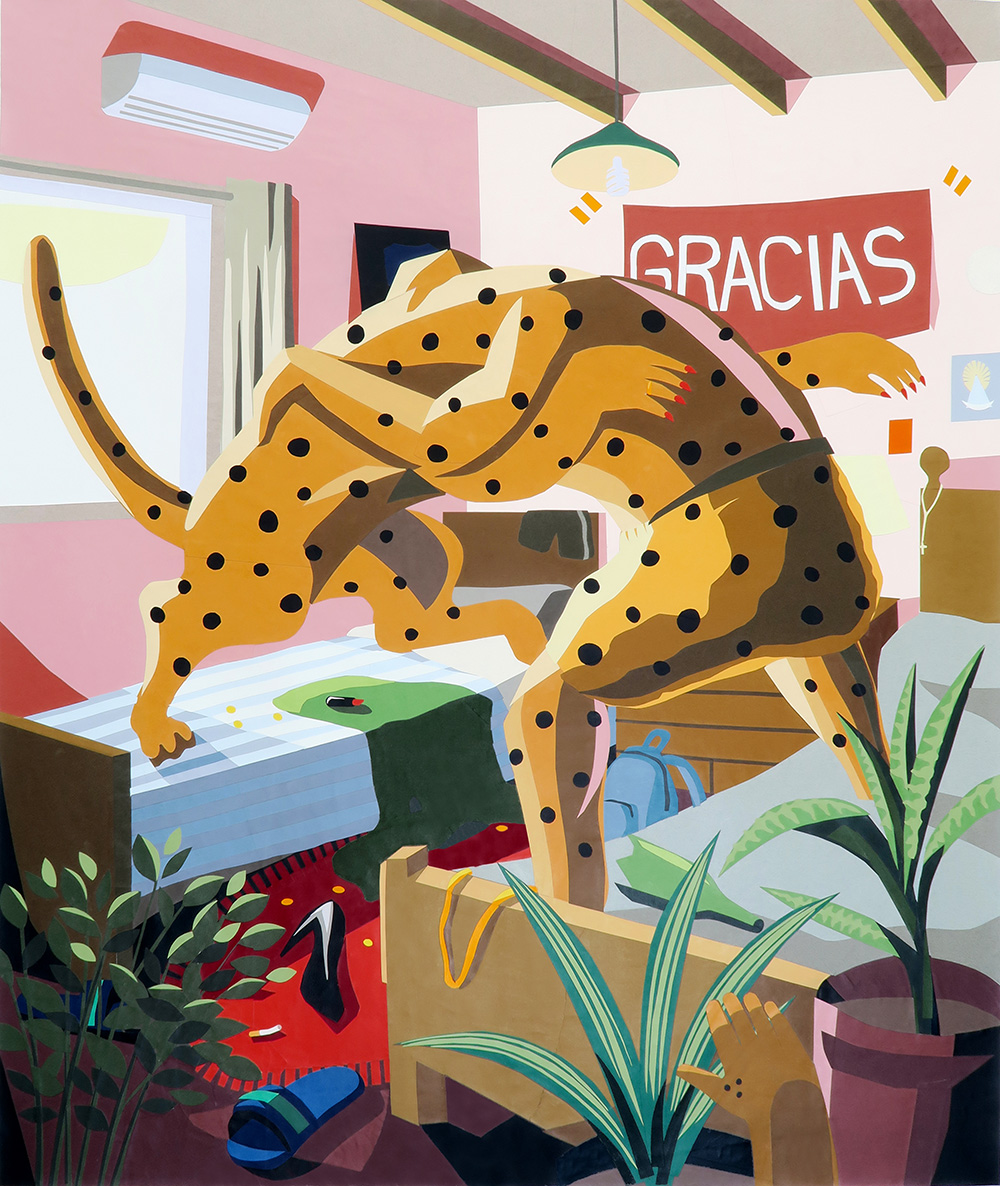

That’s evident in so much of your work. Constant struggle seems to be the theme.

I talk about society, as well as my struggle, personal struggle through societal struggle. As a mixed media artist who works in many different ways, I talk about Argentine society through my subjects. But it is extremely personal at the same time. I have always been interested in history and feel so lucky to have the chance to visit other countries and see the clash of the different realities. Geographically, Argentina is far from everything, so I see what is happening, but from a distance. I do feel the loss of the vibe that used to surround me.

Have you ever lived, say, in the country, some quiet, grassy, green place?

I was never interested in quiet places. I love those places to visit, but I love the mess! Mexico City is my favorite place in the world (next to Buenos Aires) because it is so insane, so bizarre. In just one corner, you have more information than any other place you could be. I was just in Mexico and spent some time with a documentarian. There are so many fascinating rituals. He told us about a procession for the sun, which involves a tradition of massive hammers mixed with gunpowder. In the middle of all this smashing, there is the interaction of religion and history. The Aztec and Mayan roots are so deep. Mix that with religion, and it’s insane. I could live my whole life in Mexico confounding about these things. In Bolivia, there is a tradition where they fight for the growing of the crops, a prehispanic ritual, where the flowing of blood is said to enhance the yield.

Despite the political turmoil, Barcelona is generally more calm, a city where every day I can see the same thing happening. I prefer living where anything can happen at some point.

The horses you paint show so much strength and energy.

I love the beauty and stamina of the animal. It is also related to subjects that my family of artists worked with. There is a childhood connection, and also with tigers, for example.

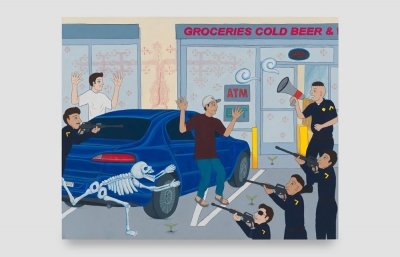

Your painting of the tigers in the bedroom, the one with the long red nails, tells a vivid, mysterious story. (Image at the top of this article)

Like someone looking through the plant into the situation, I used that to show the animal side of the person, as well as their inner energy. Also, it’s a naive way to talk through childhood, to make nicer the subjects of violence. The animals turn into metaphors.

I find collage as a juxtaposition of all these things, a more formal way to work with color, paint and scissors. I make the collage with paper covering the whole surface, then paint over in oil with the same colors. After several layers, I scratch the surface and remove parts of both. I’m still learning and recently worked this way on a massive scale, a 10 x 26’ collage. All these clashing situations, but at the same time, a fragile mural hanging by wires. So I’m exploring all possibilities of the collage.

How do you feel about working alone?

I used to share a studio with two other artists for ten years. We were friends, traveled together, shared information, shared a good vibe and grew up as artists. I miss that collaboration. The studio in Buenos Aires was a massive clubhouse with people coming by all the time. If someone needed a place to stay, needed paint, we would hook them up. The whole neighborhood got painted and embraced us.

Art is never removed from your life, is it? Do you ever go out and maybe paint a landscape? Do you ever have down time?

Art is where I find a place of calm. But I do have a singular project where I record every bed that I ever slept in since traveling as a muralist. It is totally different from any other part of my work, and not at all commercial. The act of photographing those beds is a diary of all the craziness, a way to see those places, to remember those places. I already have more than 100. I exactly remember all of them.

Franco Fasoli currently has work on view at Galerie Openspace in Paris through April 14, 2018.