It has long been debated that Bob Dylan’s folk song, “Girl from the North Country," was written about Echo Helstrom, his high-school girlfriend from Hibbing, Minnesota. When we began our conversation with Minnesota-born, Kansas City-based Rachel Gregor, whose own work depicts a distant memory of friends and families in her childhood in the upper midwest, Dylan’s visual language in “North Country” lingered in my mind. Songs and paintings of memory, childhood, the life lessons of folk tales and ballads, are just some of the ideas that Gregor has been exploring on the precipice of her new solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary New York, Cruel Babes, opening on November 16th. Where do we retain our histories from? Gregor is getting to the bottom of it.

Evan Pricco: How do you perceive Kansas City as an arts community in 2024?

Rachel Gregor: It just feels like it's kind of cozy. We have great art museums, and the cost of living is low, so it's not impossible to find a studio space. There are a lot of people who have taken old buildings, transformed them into studio spaces. And especially, if you're starting up as a young artist, it's not impossible to get a show here either. There's a lot of startup galleries. It's kind of ebbing and flowing with the real estate values.

You were born in Minnesota, which makes me think of your Still Summer series. It evokes a hazy, humid, warm night, sort of my interpretation of growing up there in the summer. It evokes a warmth and mellowness that I think is really, really beautiful.

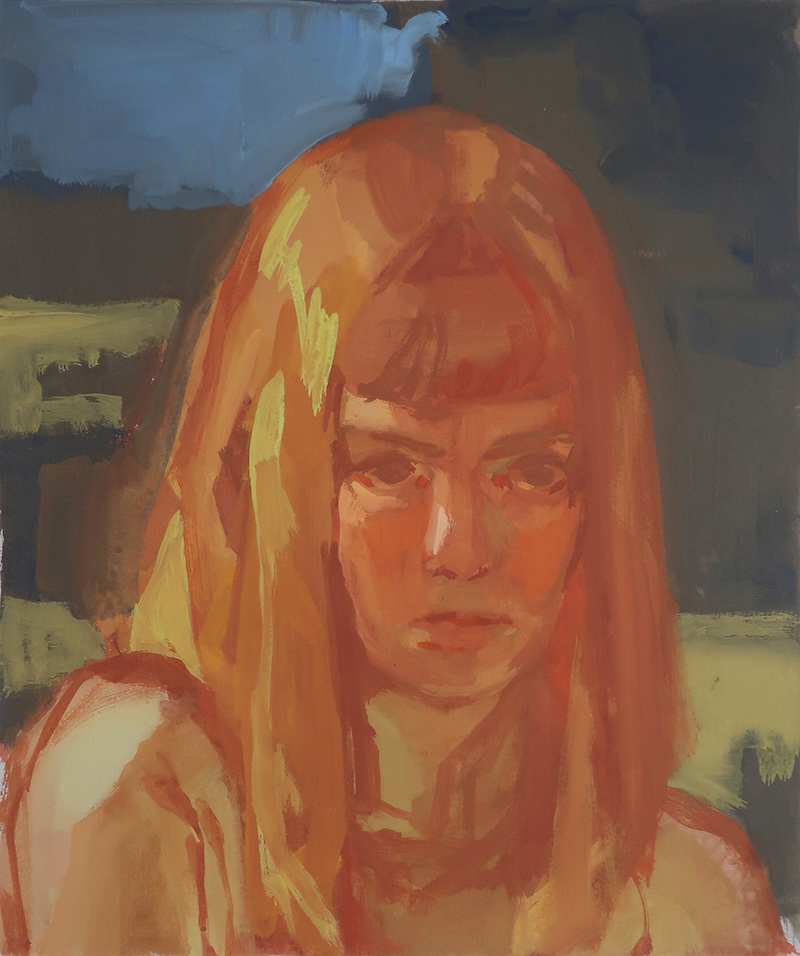

It's just kind of seared into my memory. I think the reason why I ended up using yellow ochre so much is because my bedroom growing up had a yellow ochre shag carpet that was from the 1970s and had been there forever. And so my room would always be cast in this really heavy, just overwhelming kind of melancholy, warm light.

Warm sun melancholy.

During the summer, you have this fantastic bright light, and the sun doesn't set until close to 10pm in July. I think that a lot of those landscapes have just become part of my visual vernacular. I think a lot about my grandparents' property when I'm thinking of landscapes because I spent a lot of time at their house when I was little. I always want my landscapes to have this Midwest Arcadian feel to them. I draw a lot from masters like Titian and Tiepolo, those kinds of Arcadian landscapes. But I don't want them to feel derivative because I don't want it to feel like a European landscape.

It doesn't feel like that at all. It feels very specific of a time and place.

I only know my own experiences. I am kind of more in tune with what botanical elements I put in my paintings, as well, because my parents own a nursery. They're growers. I am very familiar with what is growing around me and like to make up a vernacular of what plants mean to me as opposed to being, like, "Oh, this plant art historically is attributed to this saint or whatever.” So I'll just take that for granted and siphon off the redundant and whatever European art history you've been taught in Western Art 101, I think that kind of gets taken for granted a little bit. What does a rose mean to you? How does that fit in your own personal life? And so that's what I try to be aware of when I'm composing a landscape. And with the title piece for Still Summer, the background is that it looks kind of like a generic park, but it is actually a very specific park that is near my parents' house where we had gone to a lot in school. Even if it's just a park bench, to me, it’s a specific park bench. I hope that distinction then comes across to the viewer.

I imagine that growing up with parents involved in such a creative endeavor as a nursery, where the colors and arrangements of flowers and plants, as well as their size and proximity, needs to be orchestrated, would be a similar experience to an artistic practice.

My parents grow all their own material. And so one of my chores, as a kid, was we had this one greenhouse that was a smaller hot house where we'd start all the geraniums. It's just 30 feet of geraniums or more, and my job was to deadhead all the geraniums so that they would be in flower when it's retail time. I think about the color, but then the smell. When you're deadheading hundreds and hundreds of geranium stems, there's an orange oil that will just build up on your fingers, and oh, I hated it. That's one of the most visceral memories I have. I did a piece for the group show at Hashimoto, Lush, called Insomnia, that’s of a girl clutching geraniums because sometimes when I'm up there working, I can't sleep and have work dreams. I'm just moving flowers around and moving geraniums around, and that’s part of me, literally, my stress dream.

Is there an olfactory element in your paintings?

I think about that a lot, actually. Or what might my paintings taste like? I want them to taste astringent. At first you think this is bright and colorful, and oh, it's going to be a fun fruity cocktail. But then you take a sip and it's, like, actually, this is really bitter, and I wasn't expecting this. I was talking about that geranium oil, things like that, musty basements, or if it's just kind of so humid that just any smell lingers, and so you smell dead leaves, earth, whatever. Things like that.

What is the focus of the new show, Cruel Babes, at Hashimoto?

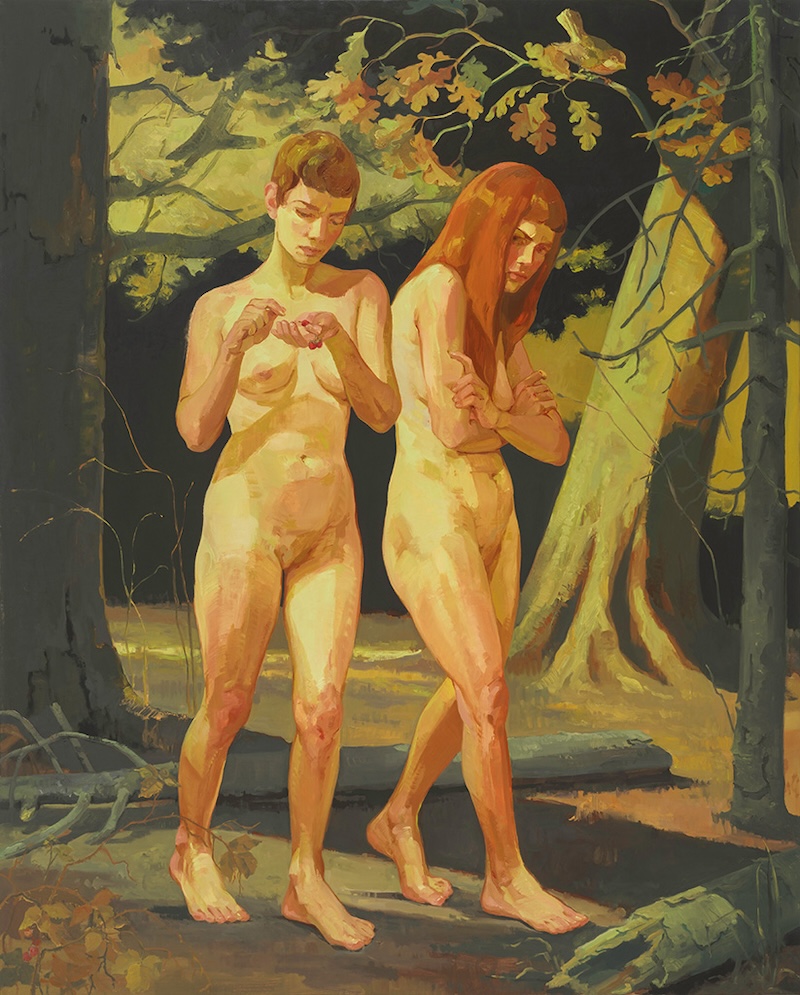

The previous show was kind of this Arcadian landscape of figures as nymphs. And so they're kind of these midwest girl nymphs who have weird social dynamics between them. With my new show, I wanted to lean into that a little harder. I have been listening to a lot of traditional folk ballads and just thinking about traditional folklore, narrative and mythology, so I'm going to draw a little more directly from that.

For one example, there's a ballad called “Babes in the Woods,” and I really want to depict the scenes from this ballad, just not in a very literal way, but in a way that relates to me. I have 3-part paintings that depict the story about children who essentially go into the woods, get lost and perish, and I read it as a loss of innocence. So I thought, who are these babes who go into the woods? Is it me and a past friendship? Why did they get lost? Did they start arguing? Was there such emotion, just a friction that they couldn't get through? And then for me, that song then became a narrative about lost friendships.

I think why I want to pursue these narratives, or folktales and folk ballads, is because a lot of these stories, especially the English and Anglo-Saxon folk ballads of the 12th century or earlier, have been told through Victorian times. They had a purpose. They had an educational agenda. But then the female ballad singers also took a lot of these songs and reinterpreted them and put in their own meaning. So a lot of these ballads became songs about inequality, or in a way, about women's rights, because women didn't have any other context or voice to express how they felt. But they were able to take these songs that were written by men hundreds of years earlier and represent them in a way where they could relate to them, they could feel empathy or sympathy and express their own troubles. And I think that's also why I relate to a lot of these stories too because; like, how do you re-examine this and find the empathy or the human connection in it? And a lot of these stories now, we have no idea about them or why they were told, yet throughout humanity they were teaching us lessons. I think it's important not to forget about a lot of these folk songs and folktales, and represent them in a way that demonstrates they’re still relevant because they are. They're still stories about human suffering and how to feel empathy with one another.

We seem to think that people from the ancient past didn't have the capacity to feel the way we feel today, as if they lacked the ability to feel complex feelings or something like that, or they wouldn't have been this way or that way because those ideas wouldn't have existed back then. And it's like, no, our brains have evolved very, very, very little since when we were cave dwellers. Our brains are the same. We had these complex emotions. We have always had these complex feelings.

Rachel Gregor’s solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary in NYC will be on view November 16—December 7, 2024. This interview was originally published in our WINTER 2025 Quarterly print edition.