Few things in life are as startling and oddly miraculous as a chance encounter with a spider’s web. These light-catching traps are constructed with impossibly thin silk threads linked together by a creature hell-bent on luring us into its space. It is not a benevolent invitation, but it is equalizing and necessary, and simply part of nature for the spider to sustain itself. The activity of building a web is decisive and tedious work, but it also appears to be creative to some extent, and in many ways the endeavor mimics the journey of an artist that is equally compelled and obsessive.

Hayley Barker and Shari Urquhart meticulously attend to every inch of their artworks using incredibly small gestures and repeating patterns, from corner to corner. Each artist drifts across large expanses of two-dimensional space using diminutive art tools made for detail and precision. For Barker, the same small paint brush used to apply oil paint onto giant canvases in irregular but repetitive strokes is used for her much smaller paintings, often creating a vibrating effect that helps define the energy and feeling of the spaces and objects she chooses for subjects. For Urquhart, delicate loops of wool, yarn and string are slowly hooked, one by one, to reveal complex narrative scenes that often span more than ten feet across.

Separated by generations, Barker and Urquhart both endeavor to speak truth about their existence and the immediate world around them through their crafts. As artists, they place themselves and elements from their private lives on public display for us, the viewer, even if these images are sometimes veiled with layers of fantasy, memory and personal mythology. Both artists engage with surreal moments in their artistic practices, but they each find their deepest inspiration in real encounters and settings, which have been carefully chosen to highlight deep threads of feminism and spiritual awareness.

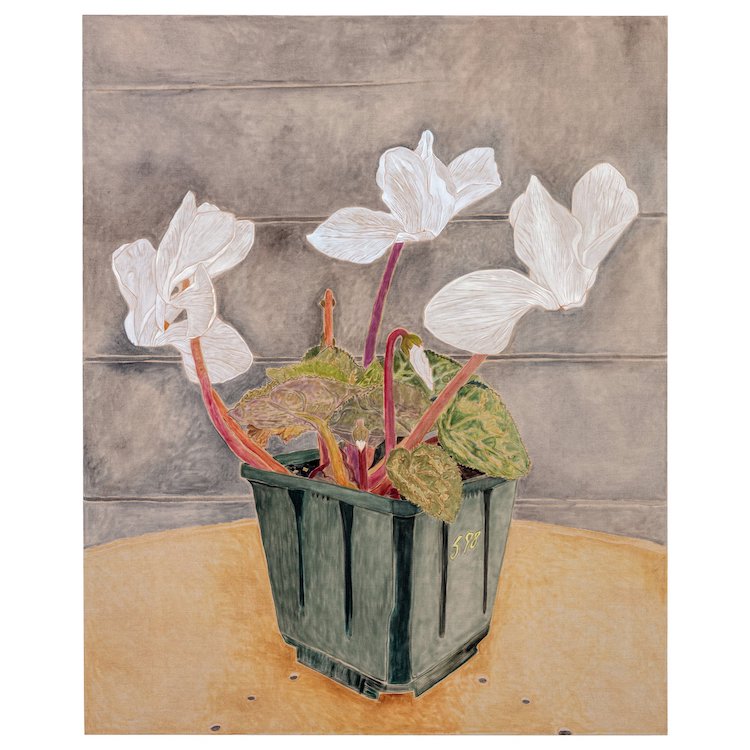

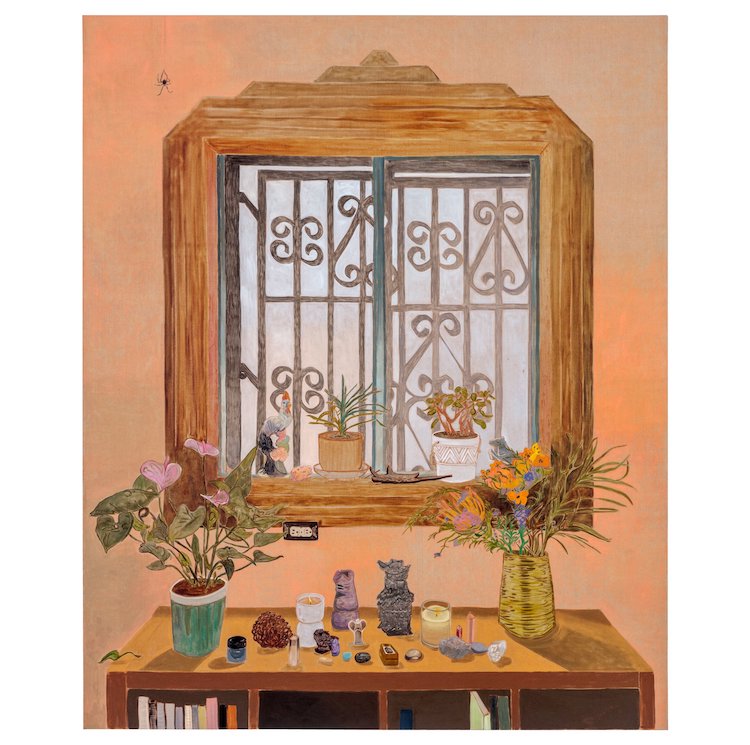

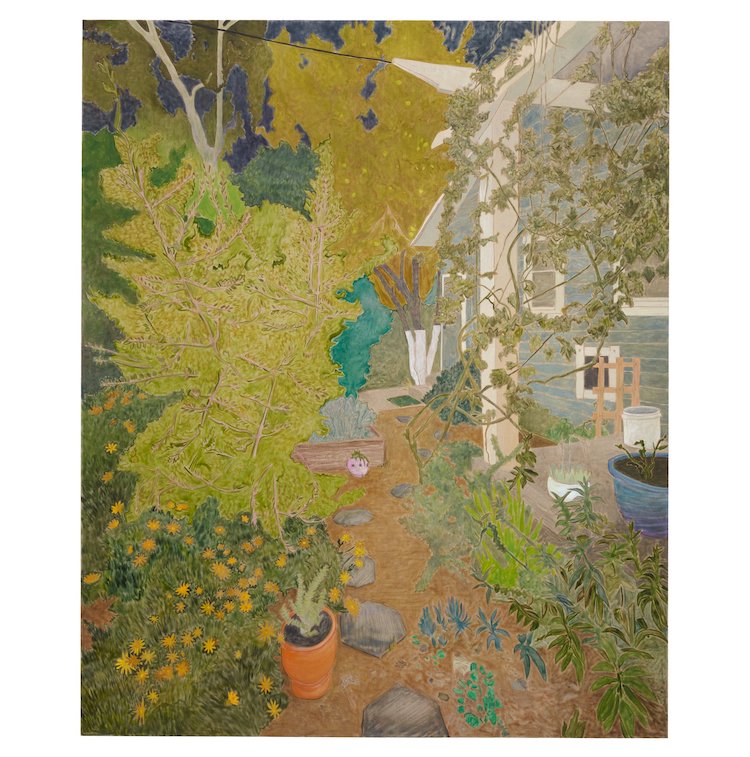

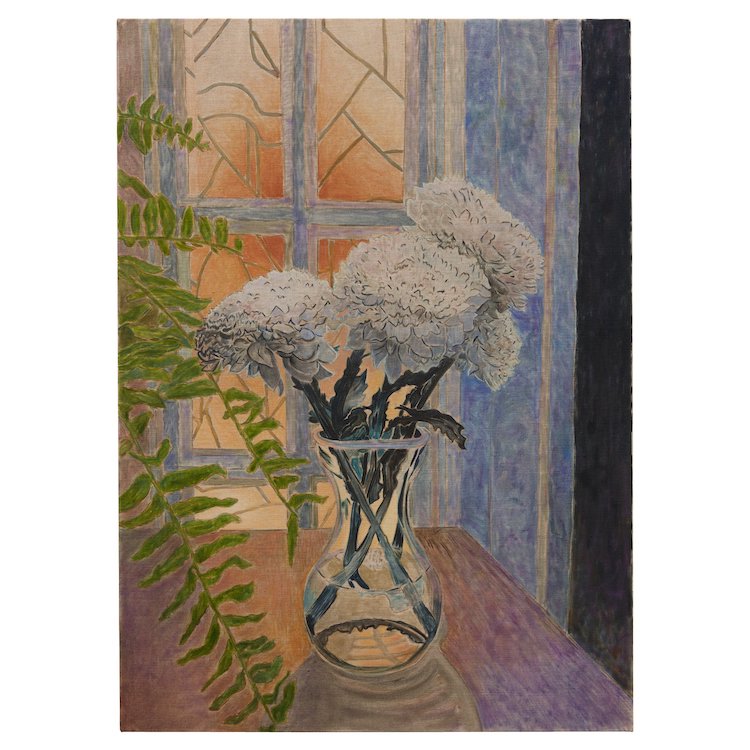

Realistic but otherworldly, Hayley Barker’s canvases explore rituals and humble day-to-day experiences, including her interactions with a garden that has become her primary muse. Maintaining this outdoor space is part of her daily art regimen, and the planting and care of these living entities is done with love and heartfelt intention. Each plant’s placement in the yard and how it is tended is viewed as a performance in Barker’s eyes, and the compositions she creates with plants and greenery are for the benefit of her home but also designed to suit her needs as an artist, providing the backdrop for intimate still-life and landscape paintings. In oversized-canvases like Cyclamen, the artist heightens the beauty and spiritual feeling of small moments and details that often go unnoticed. The rusted metal stool in the foreground of the painting almost seems to breathe, and the yellow handwritten price on the cyclamen’s green plastic sleeve was clearly applied at a small nursery and not a mega-store. It’s subtle, but intentional, and in its own quiet way provocative.

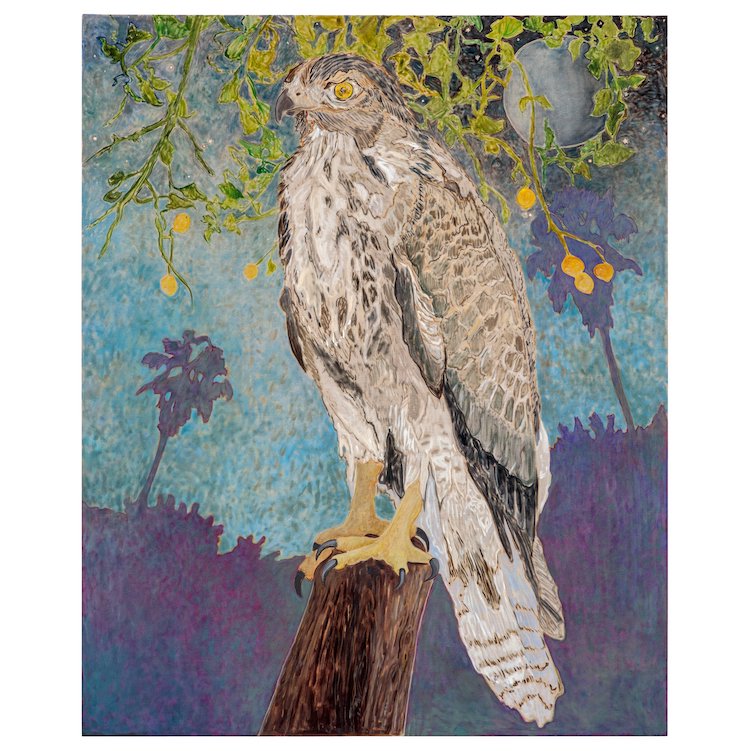

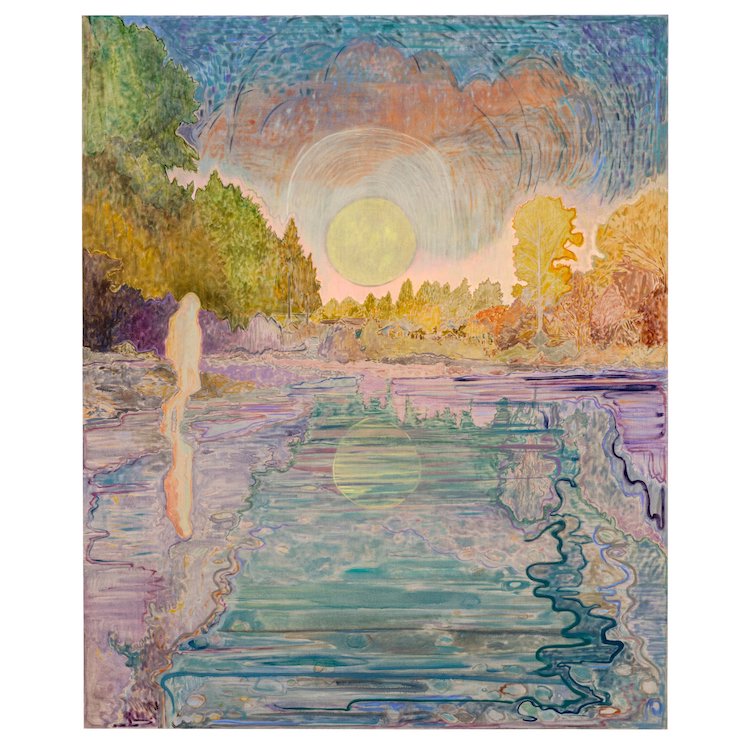

The underlying layers of sentiment, personal acknowledgement and meaning in Hayley Barker’s new works is simple and austere, and as an artist she brings us into her most sacred and personal spaces. We quietly join her during a magical encounter with a wounded red-tailed hawk and view an altar created in her new studio to remind her to respect her intentions, prayers and to always give gratitude to the universe even when it is not easy. In Jennie at the River (After the Fire), which documents Barker’s favorite childhood swimming hole and a year after a large fire destroyed the area, Barker shows us a visage of the forest and river coming back to life after tragedy. There are of course less trees and more sky than before, but the surge of growth and renewal is palpable. Hayley and her friends privately call this spot Riverwood, and the location has become one of her most explored and repeated landscapes in recent years.

Shari Urquhart (1940-2020) was a lifelong artist and teacher, and despite almost touching meaningful artistic success while living through her inclusion in Marcia Tucker’s ground-breaking exhibition, Bad Painting at The New Museum in 1978, her works still remain widely unknown despite the feverish level of artistic production that consumed her life. Born in Racine, WI in 1940, Urquhart later attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, earning three degrees including a teaching certificate that she would make use of for rest of her life.

Like many aspiring artists of her generation, Urquhart moved to New York City to follow her dreams. In order to pay the bills in a new city, she took a full-time job in the fine art workshop for prisoners at Rikers Island Correctional Center from 1978 to 1982. This job eventually led her towards the St. Francis Residence in NYC, where she became the lead of the facility’s art program for more than 25 years. St. Francis offers permanent housing to one of the most vulnerable homeless populations, individuals living with severe mental impairments and illness. Urquhart was a generous and compassionate instructor and inspired many of the home’s residents to discover themselves as artists over the years, but her true passion was her own art career which explored the traditional craft of hooked rugs made using Persian wool, satin, mohair, chenille, yarn and occasionally her own dog's hair.

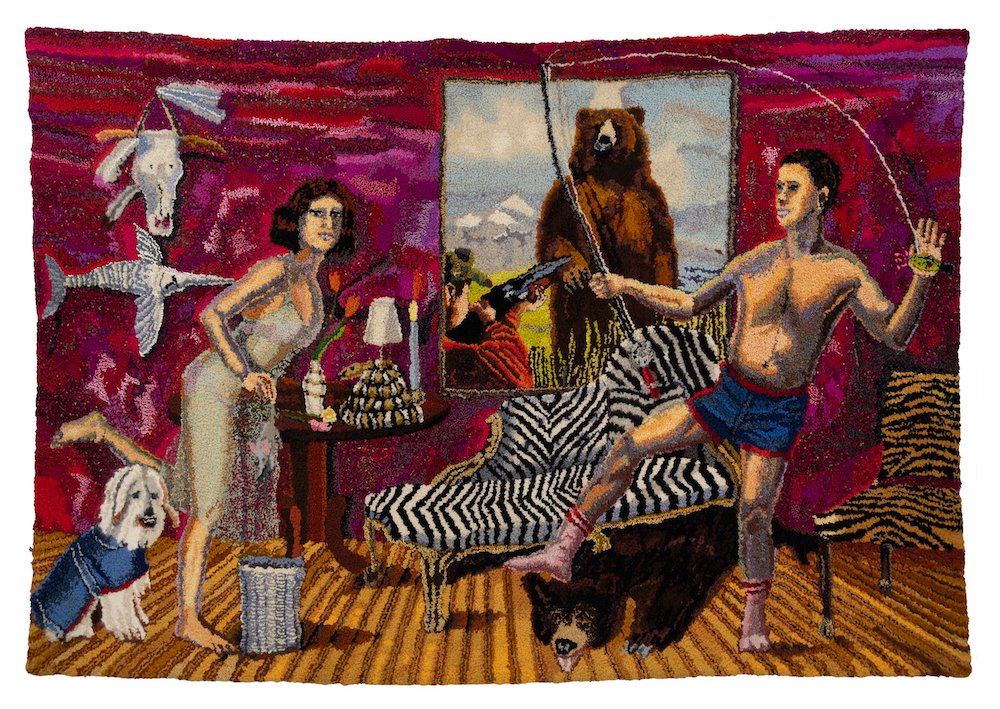

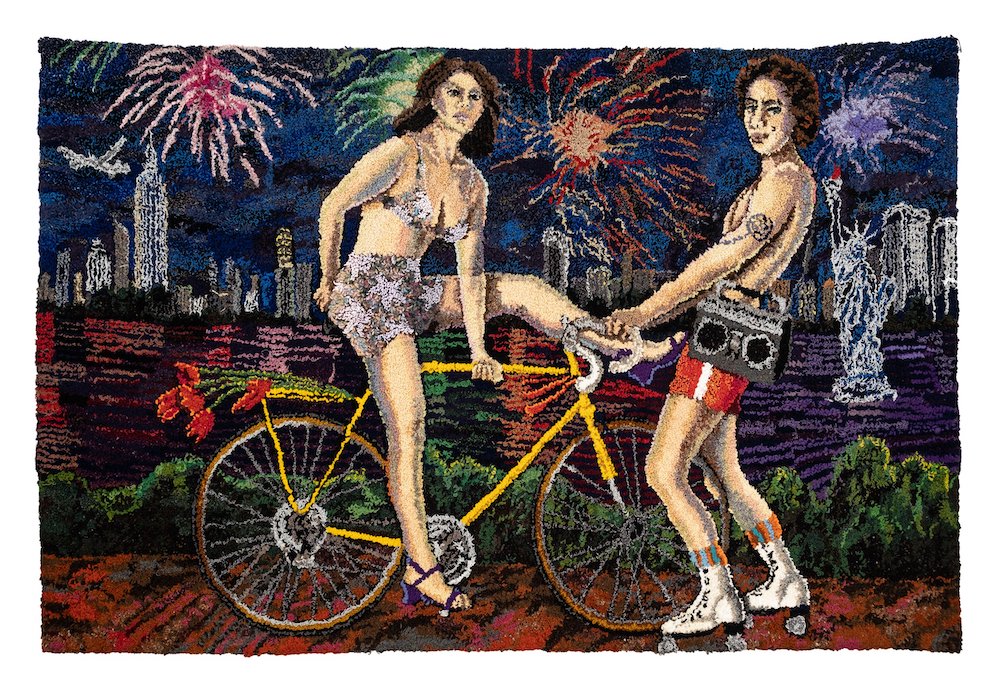

Urquhart deserves credit as a pioneering force in the history of art given she blurred the lines between the very traditional craft of hooking rugs and contemporary painting. Utilizing a medium not often associated with “fine art”, she created wildly-themed narrative hooked rugs that are epic in scale, with some measuring more than eleven feet wide. The process of creating hooked rugs is incredibly labor intensive, and the artist often spent an entire year creating just one large piece. In a sense, Shari Urquhart helped break painting free from its reliance on classical art materials such as brushes and paint, and her complex textiles all resonate as odes to both the humor and tragedy of human existence.

As an artist, Urquhart typically highlighted the disparities and conflicts between men and women. In several of the artist’s hooked rugs, a lone man and woman serve as archetypes for each gender, with both sexes frozen in time during surreal, interactive moments that have gone awry and feel ready to explode or right themselves. In the singular work, Woman I, Stage III, her sentiments are more direct– A female in a sheer black negligee is surrounded by a swarm of miniature nude men fluttering around her with fairy (or insect) wings. Distracted and amused by their own shadows, the small flying men are oblivious to the fact they are pests and that this giant woman is armed with a fly swatter.

Hovering in the background of this work is a framed copy of Odilon Redon’s famed smiling spider, both a nod to Urquhart’s keen awareness of art history and also a reminder that the smiling spider is only fulfilling its destiny when devouring its prey. In uncanny alignment, Hayley Barker wears the exact same grinning spider on her right arm as a tattoo. It’s a sign. As artist and friend, Amy Bessone, offhandedly mentioned, “I spy the Redon spider, that’s a common thread. And now that I think about it, you construct your paintings like a spider weaving a web.” The same holds true for Shari Urquhart and her threads.

The Spider is on view at SHRINE through May 21, 2022.