pt.2 Gallery is honored to present News from Nowhere, a collaborative presentation by Liz Hernández and Ryan Whelan for the 2024 edition of The Armory Show. News from Nowhere explores visions of utopia focused on the interconnectedness of humanity and nature, viewing utopia not as a destination, but as an ideal we strive for.

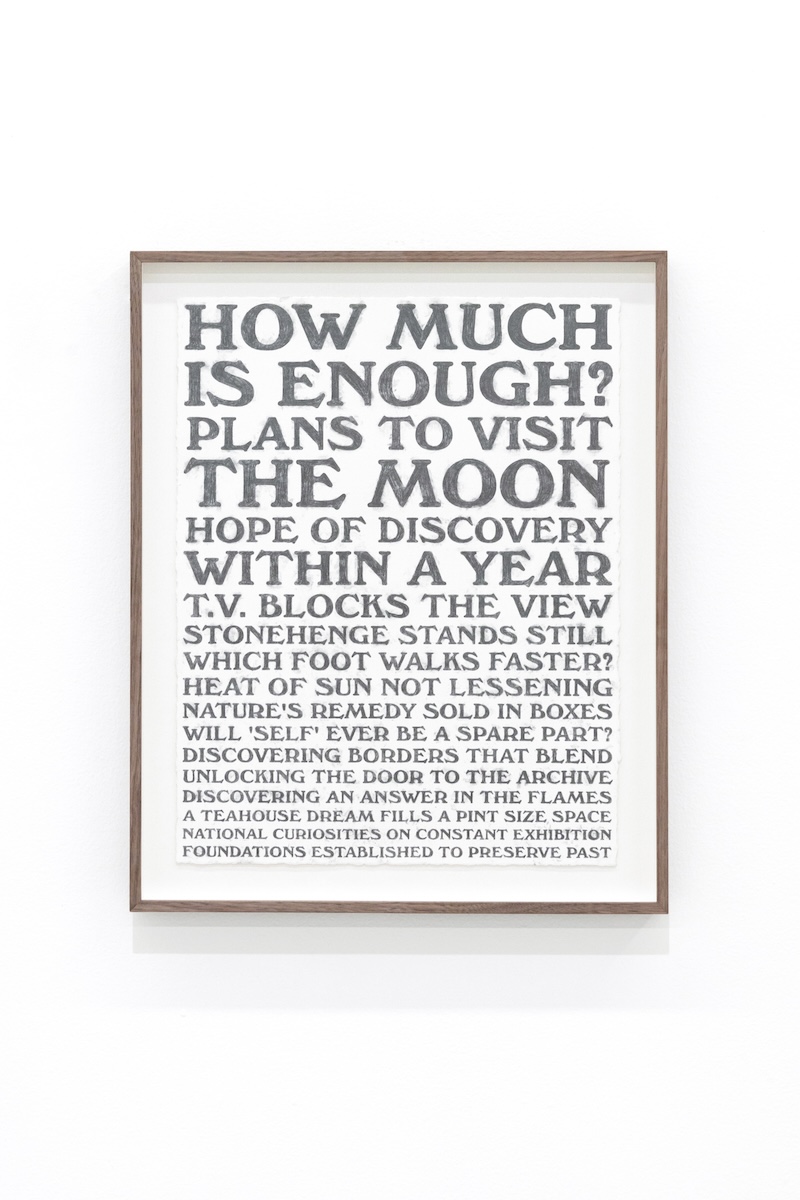

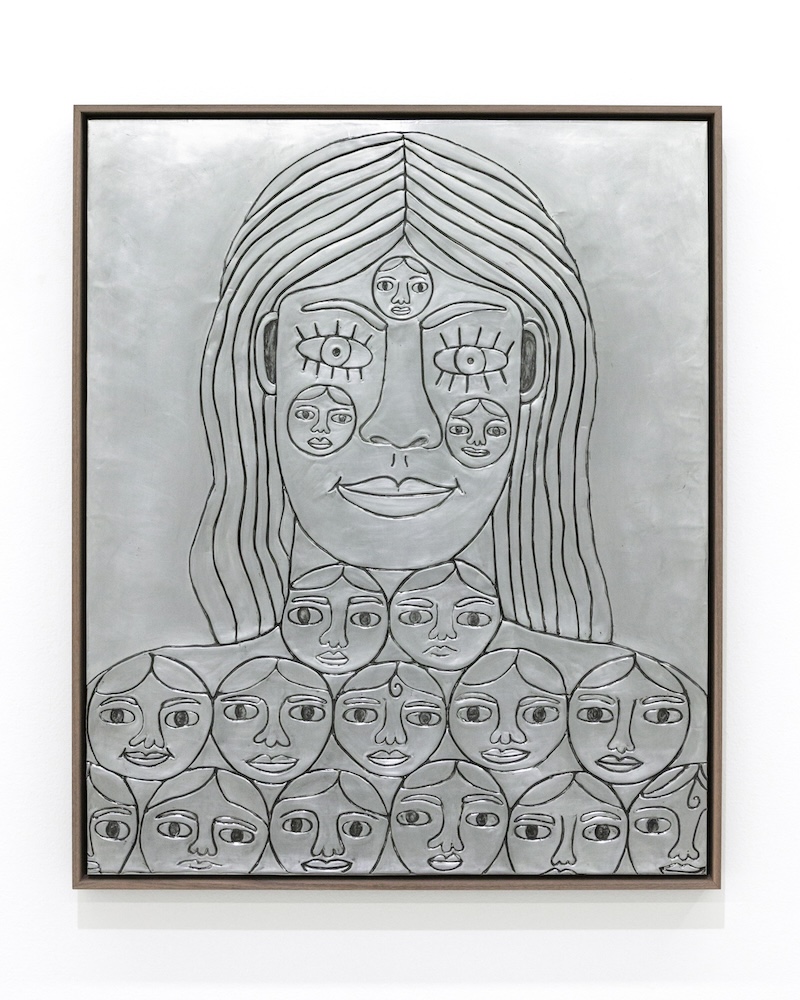

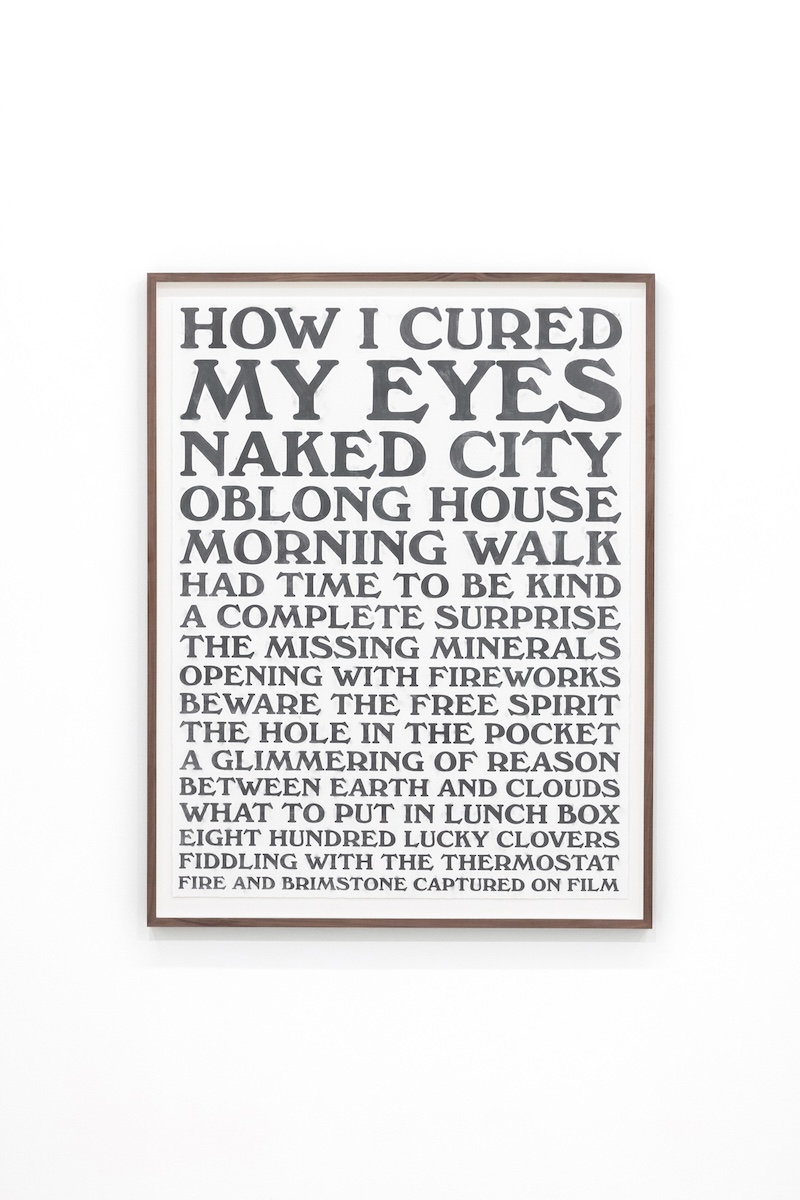

Hernández presents paintings on Amate paper, a handmade paper originating in pre-Hispanic times, and embossed aluminum reliefs portraying scenes of humans and nature in a reciprocal, communal exchange. The writings of Mixe linguist Yásnaya Aguilar, 15th-century herbal manuscripts, and William Morris’s ideas inform the utopian vision envisioned in Hernández’s imagery. For Whelan, pattern-based paintings depicting abstracted, organic forms, at once familiar and new, pose an exploration of utopia as an open-ended notion; a shifting horizon shaping how we reimagine the alienation and flux of the now. Grounded in the ideas of William Morris, Adolf Loos, Charles Burchfield, and the Hippie Modernism movement, Whelan’s focus on surface, texture, and light opposes the smooth object, expanding compositions intended to “fill the eye and satisfy the mind,” as Morris wrote. For a group of text-based drawings by Whelan, headlines from newspapers since the late 19th century become concrete poetry that, like the forms of his paintings, leaves mystery and room for imagination. Through their individual practices, Hernández and Whelan’s News from Nowhere recasts modernity and progress as an optimistic endeavor, connecting to nature, and drawing from past philosophies, to find space for the soul.

As progress compresses time, time has begun to eat up space. The industrial process has reached an unholy key of abstraction: technological advancement is consuming the world’s forests to replace what imagination does for free.

Utopia is a funny idea. It’s an ideal that, if ever reached, vanishes. Its idealism is a propelling force, similar to the inertia of progress, in which the dream gets sucked up back into the machinery.

People in pursuit of utopia, of ungrounded pleasure, fall into the trap of “no place,” losing the world to nowhere. Utopia, progress, and the logic of technological innovation conveniently take away the real and its responsibilities. But what’s left?

In Mixe linguist Yásnaya Aguilar’s essay “A modest proposal to save the world,” Aguilar posits that a radical understanding of general reciprocity might undo the environmental ruin of insatiable progress. She argues that we must understand our neighbors as fundamental to our own lives and extend that definition of what it means to be a neighbor to include living, but non-human entities, like water, soil, or air.

“You are part of a place,” Liz Hernández says, “like it or not.”

There is a clarity in her work, a directness that personifies the animism of nature in drawings of telluric souls. Hernández’s paintings are not abstract, they depict the elements in allegorical scenes. Here water is a companion and the earth is a person sitting beside you. The depictions work against the sensorial numbness individuality invents, countering the technology of self-hood and insisting that each one of us belongs to many others.

Both Hernández and Ryan Whelan’s work has a physical quality. Whelan paints with the by-products of industry, populating his paint with sawdust and factory waste. Hernández carves into aluminum, a traditional decorative art in Mexico, where smooth tin is marked through with lines of concavity.

Here, the art works are imbued with animism, existing as an overt invitation to be taken up. The work extends beyond the point of its construction, finished only in context, in the moment of reception. There is a generosity to this suspension. The image is simplified. Something mysterious and novel lives inside that simplicity, waiting to be recognized.

In ‘Art: A Serious Thing' (1888), the British designer and socialist William Morris writes of the painting as a kind of window. The painter, as a window-maker. “A painting can be a mirror where you don’t see your face,” Whelan considers, “you see, instead, what you are searching for.”

His paintings put nature in a close frame, imagining a proximity textured by context, enmeshed in fauna. Nothing is just one color and the paintings exist in a provisional state, alive and animate, suspended just before they reach an ending. It brings to mind philosopher Timothy Morton’s description of nature as a “hyper object” that you are never aware of as a singular entity, even when its caressing your cheek.

There should be a miracle section of the newspaper, the smooth object of Austrian modernism should be decorated, flash for a second to the Hungarian artist Agnes Denes tilling a wheat field in a landfill at the edge of Manhattan.

There’s novelty to looking again at what has already been seen a thousand times; It’s avant garde to not need anything new — to be satisfied with seeing the already existing world.

Written by Theadora Walsh