Plato is beyond excited to present Ákos Ezer's first solo exhibition with the gallery, Living Room Campout. The Hungarian artist’s signature long-limbed characters, both painted and sculpted, so beloved in Europe and Asia, are finally coming to New York, equipped with sports, camping and party gear and ready to teach us lessons in art history, politics and social graces.

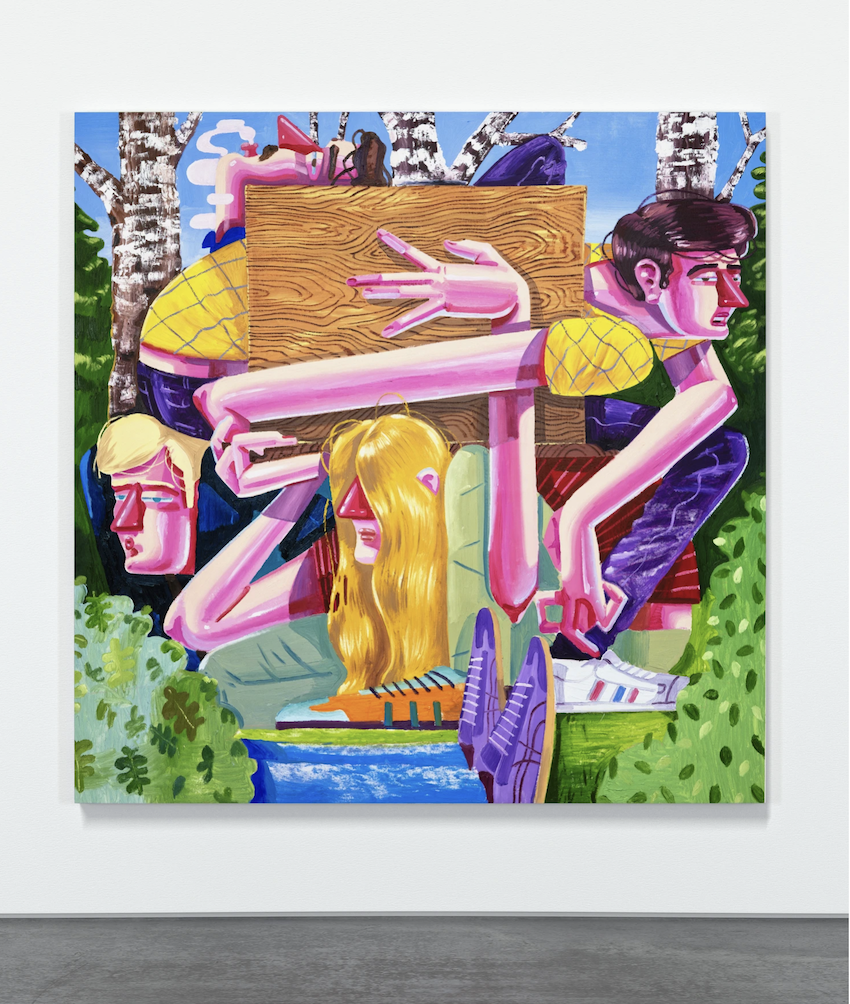

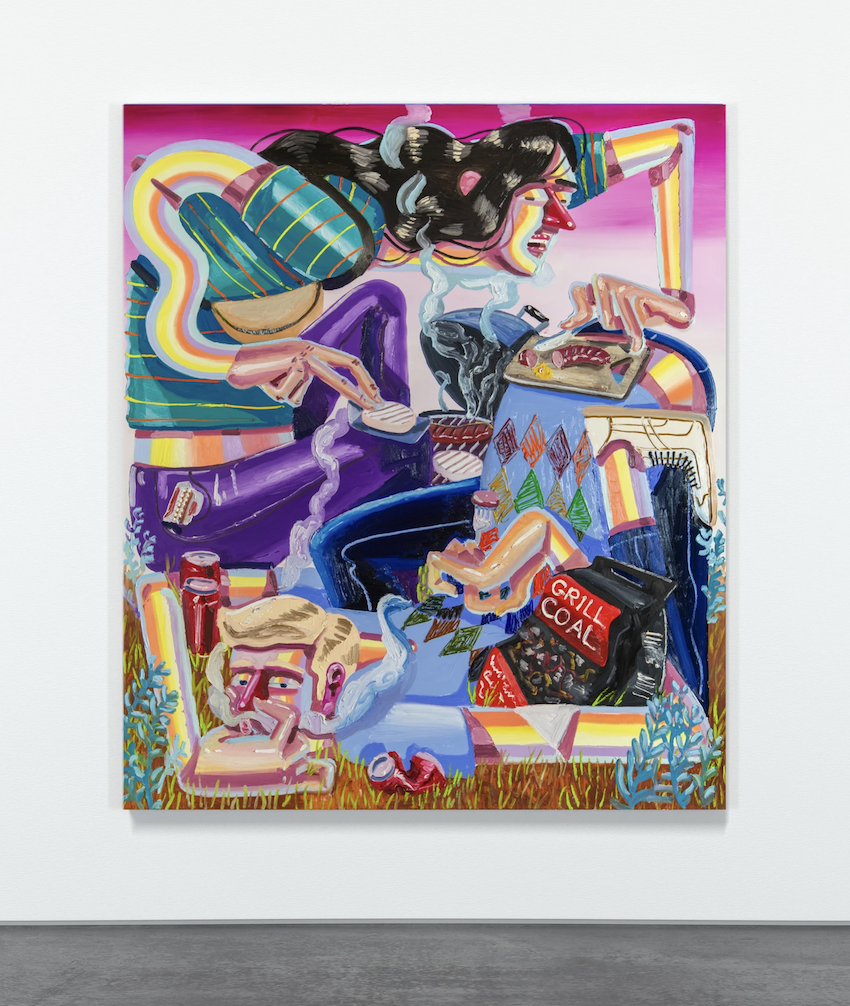

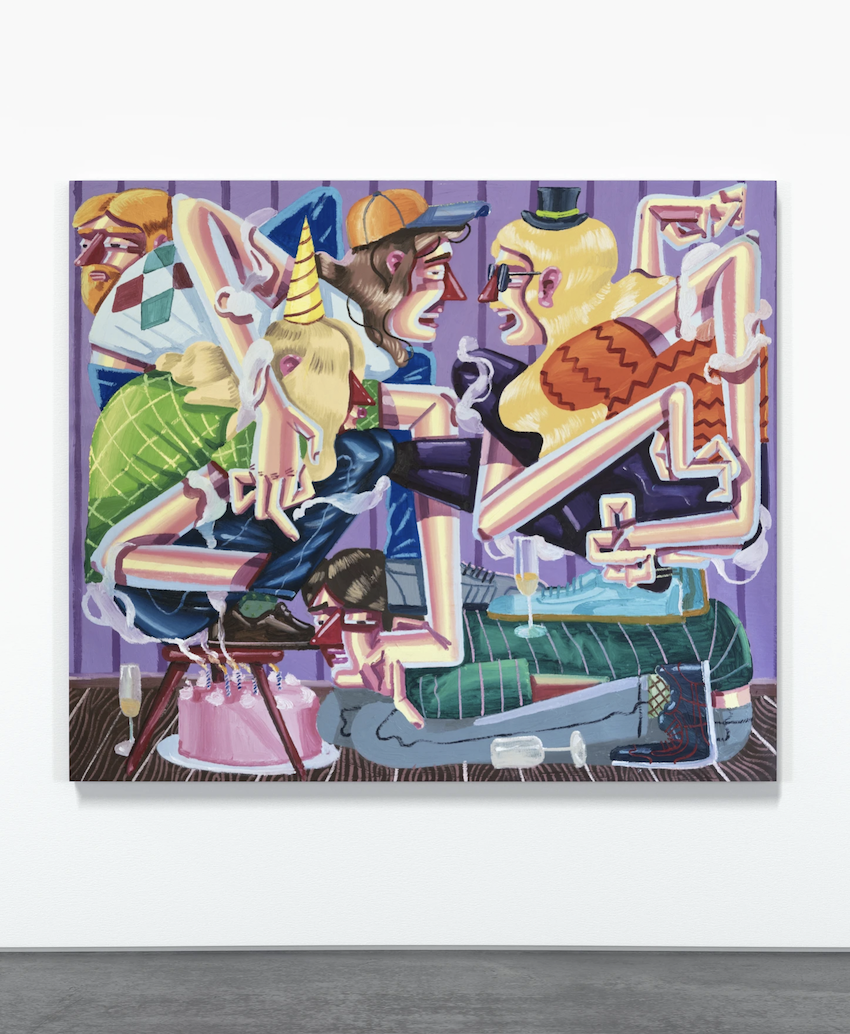

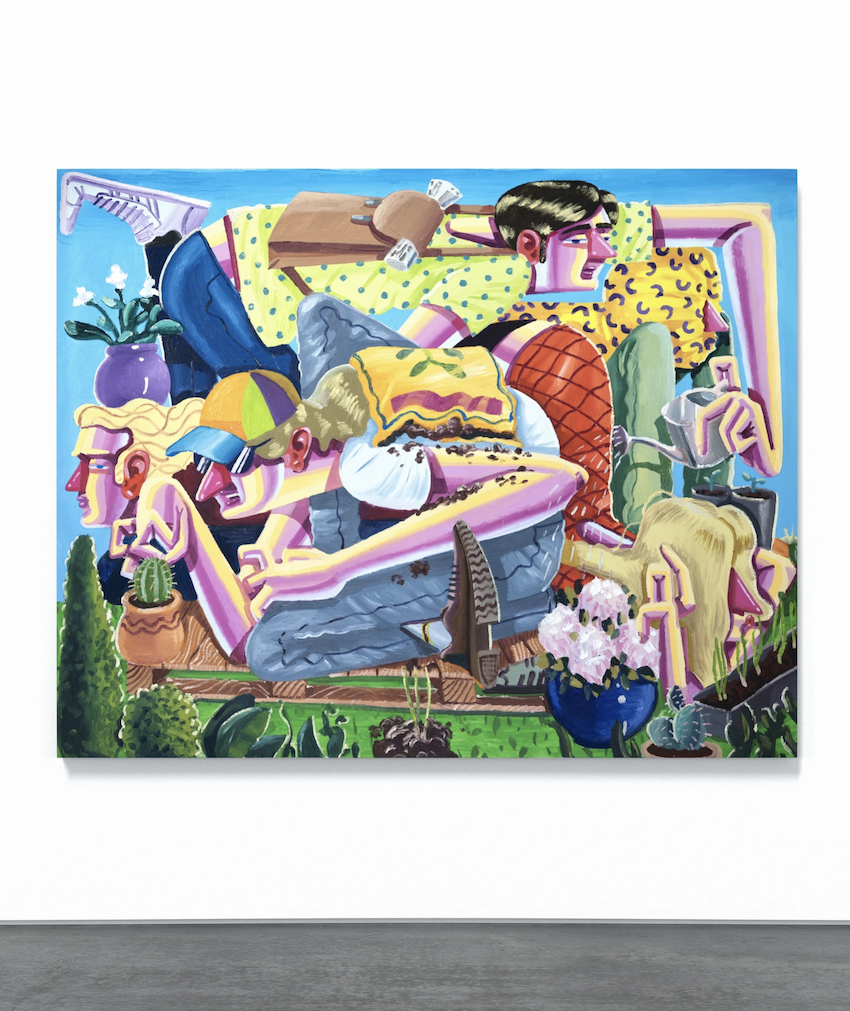

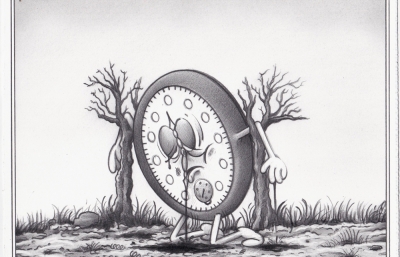

The brooding European hipsters in Ezer's works resemble masked actors in Italian commedia dell'arte. Yet contrary to the type-like Pulcinella and Harlequin, Ezer's twisted figures, being his own ever-evolving alter egos, morph and change roles and personalities from painting to painting. Shy wallflowers turn into the souls of the party and trampled losers come out on top. Golf-playing bullies and charcoal burning carnivores transform into garden-planting dreamers. Not necessarily bearing his characters' exact semblance, Ezer identifies with their changing dilemmas and personal and group predicaments. Besides, in a world where the limits of freedom of speech are ever-changing, what and who you depict to express the truth has to be equally fluid.

Trained in the tradition of European art academies, Ezer eventually rebelled against photorealistic appearances and finish fetishes, yet his cartoony figures and candy-colored surfaces are steeped in centuries of painting tradition. The drama of the repeated diagonals and the contorted bodies squished within the picture frame follows the cues of Caravaggio and other Baroque masters. While androgynous youngsters involved in leisurely activities pictured in precarious poses with bright, often pastel-like hues harken back to Rococo painters. Propping the sky with a foot in Planting could come right of Fragonard's Swing. Watteau's Pierrot, another iconic character of the Rococo repertoire, is an obvious prototype for Ezer's theatrical figures, often lost in thought right in the middle of the action. The artist treats painting as entertainment, delighting in showing off his virtuoso brushwork. He freely switches from luxurious, sticky impasto to flatter areas and back again, while constantly prompting us to question whether what we see is a real world of dreamy youths or an agglomeration of abstract shapes and paint strokes of various length and thickness.

With their angst and doubts, Ezer’s clumsy characters playing sporting, table top, mind and other types of games, and navigating the changing rules in order to stay afloat — or simply sane — are infinitely relatable. Even their avoidance strategies of awkward yet balanced crouching while smoking, whistling or smelling the grass seem more like nonviolent action. Despite their existential struggles, these figures live in a world of vivid colors, sunny landscapes and cozy, well-lit living rooms equipped with all sorts of gaming accoutrements and consumer goods. They are youthful and loveable, endowed with superhuman flexibility that makes them formidable jugglers capable of withstanding all sorts of pressures. In the words of one of the greatest players of all times, Michael Jordan: "I've failed over and over and over again in my life and that is why I succeed."