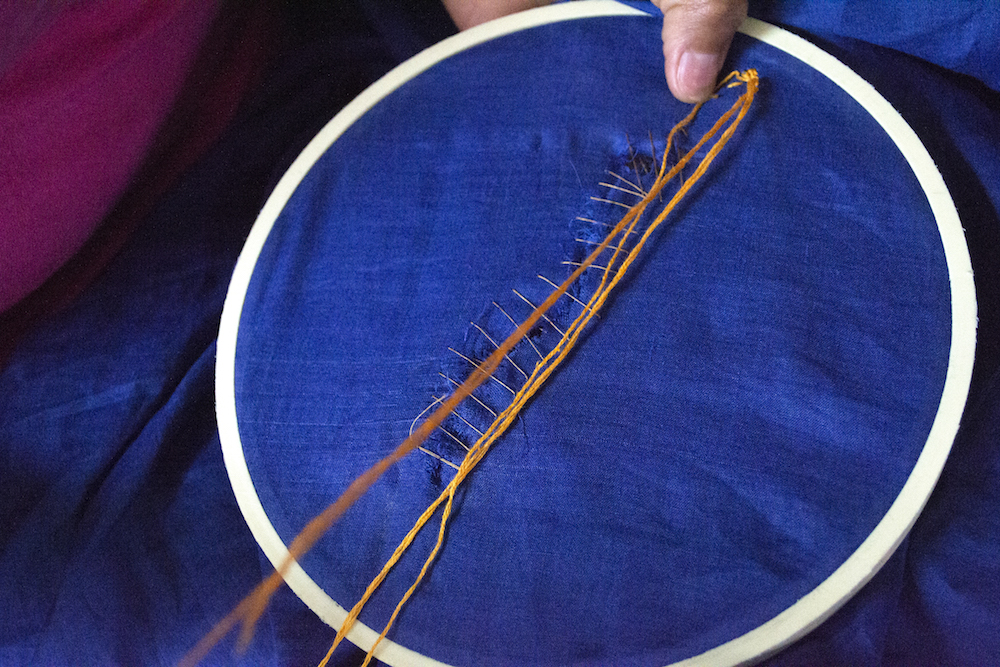

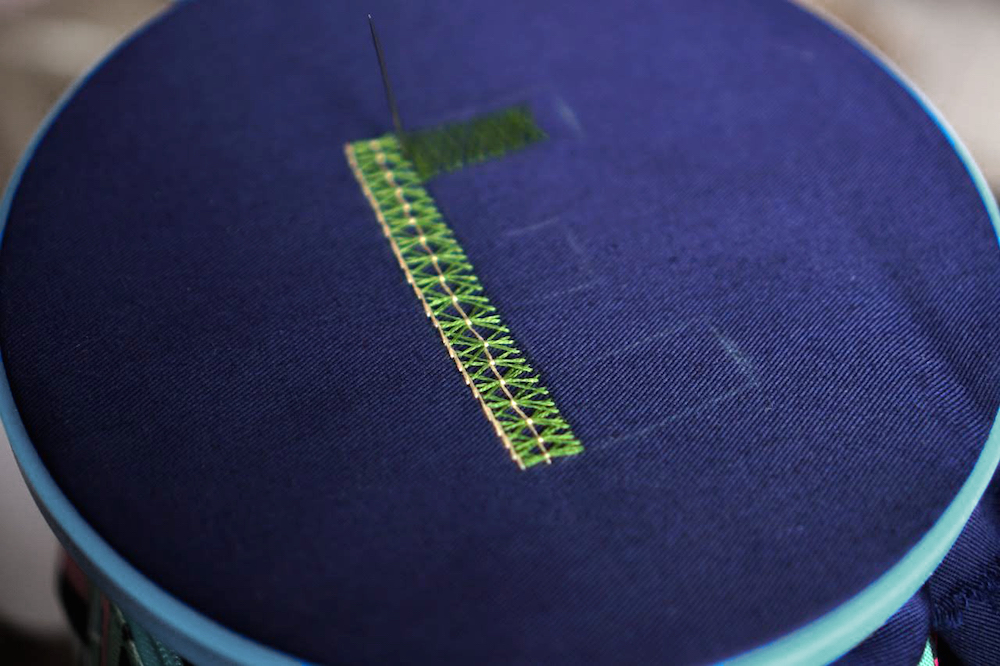

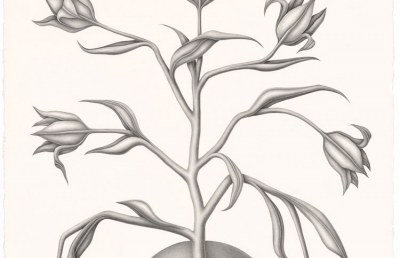

It’s not frivolous, and it’s certainly not fast fashion. Nor is it a uniform of basic black on black on black. In fact, the richly imbued indigo blues and carmine reds seem condensed from the sky and soil. Carla Fernandez designs with an ethic firmly stated in her Manifesto of Fashion As Resistance. The clothing she creates is modern in ease and adaptability but rooted in a tradition that respects land, workers, time and technique. From leather fretwork, to bead and Rococo embroidery, each piece is handmade by local artisans of Mexico, and “our clients become its custodians.”

Gwynned Vitello: This is kind of a chicken and egg question, but which came first for you, an interest in what we’ll call fashion, or a drive for social justice?

Carla Fernandez: Since I was very young, I was involved in the world of… I don’t know if I would call it fashion or not because, for me, my passion comes from the way of dressing in communities. Some people say it’s fashion, others don’t. It’s clothing, you know, it’s a way of expressing yourself through clothing. I think we work every day in our business to combine both, so I don’t really think you have to choose one or another. I do think it’s time that the fashion system be done in a more equal way.

It sounds as though your childhood fostered empathy, an awareness beyond your own needs.

I was born and reared in the north in the frontier of Mexico and in the United States. My mother was quite a fashionista, so I knew pretty much what fashion was about. But from my point of view, I felt that the best dressed in my country were the men and women in the communities. They had a sophistication that I didn’t see in the shopping malls in the United States or Mexico. I had an eye for what I saw in the country—the highlands, mountains and deserts, not in the fashion malls. The way of dressing in the indigenous communities is amazing. It’s comparable to the haute couture houses of Italy.

Did you spend a lot of time in the countryside?

Every single summer, I would go visit my grandmother, then go visit the shopping centers in Houston and San Antonio, and became aware of what was going on there. On the other hand, my father was a national director of anthropology, so every time there was something at the pyramid, we would go with him, and there, besides the countryside, I was able to see this incredible way of dressing. So, being born in the north and with my father often working in the south, where the indigenous communities are based, and me living in the center, I have known my country pretty well since I was very young.

Were you taught, as a child, any handicrafts?

No! [laughs] I was just an admirer! I went to school to create my own clothing, but was not into embroidery or weaving. I wanted to create the clothing.

Did you have to wear a uniform to school?

No, and I was in school in the ’80s when everything was very dramatic and shiny. I was always fighting for my rights to dress as I wanted since I was very young. Always, always, I had very short hair, like pretty genderless. So I fought for my rights to have my head, my clothing and style the way I wanted.

Were there certain people, certain books, who inspired you to be more independent in expressing yourself?

Yes! I’ve always been fascinated by all the fights indigenous communities have regarding their clothing. In Mexico, there is a lot of racism. What’s very interesting is that when a person from the indigenous community comes to Mexico, they don’t want to be judged or to be victims of racism. The first thing they often do, as in a lot of countries, is they just don’t dress as they do in their communities. So that resistance from the people who want to be recognized and want to dress as in their communities, with their beautiful dress, was a very strong movement for me, to say, “I belong to this community and I will keep using my clothing. I’m going to the City but I will introduce my culture to this huge country that is Mexico.” In Mexico, we say that we have 68 living languages, which all have their own variations in dressing codes. It’s very interesting how this county has mixed and created all this diversity.

You must still travel very extensively. How do you go about choosing where to go and meet the artisans?

What’s fascinating about our project is that the communities we work with call us to collaborate with them, not the other way around. That changes a lot of things because, in Mexico, there are a lot of designers who want to collaborate with artisans. But then they do not make compromises and there are misunderstandings between one party and another. But when they call and ask you to come develop something because previous experiences didn’t work, or they want to be more innovative, it means you arrive as equals and sit down together and approach each other as equals.

I didn’t expect that they reached out to you, so that must mean that your company has a very honorable reputation.

A lot of time it’s through non-profit organizations. The community approaches the NGO to say, “Look, we are having problems, our product is not selling, and we want to do innovative things.” The NGO, or even the government, may know about our project, and sometimes the artisans themselves.

I admire your Manifesto of Fashion as Resistance and manual, “Creation and Justice: Steps to Avoid Fashion Waste.” You really do have a template.

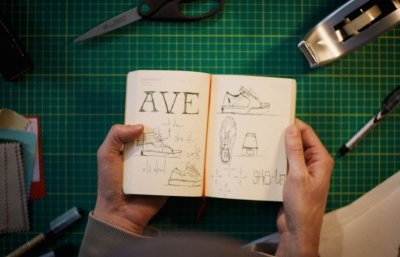

Yes! We have a manual, a book called The Barefoot Designer. It has step one, step two, step three, literally what worked for us and what hasn’t. Because I am a historian, I love to think in terms of how we can make these possibilities come true and that people will understand, in a very pedagogical way, this way of making alliances with communities.

Did you go to business school?

No, I wish! I keep saying to my friends that I would love to get an MBA, and they say, “Carla, forget it, you don’t have time.” But my business partner, she did it. I love her and she does all that part, so we actually complete each other.

Tell me about The New Denim Project and how it came about.

I met Arianne from The New Denim Project in Guatemala City during their Fashion Week when we both took part in a sustainability panel. I was very excited to learn about her method of using recycled denim that does not involve water or chemicals to weave the denim again. Since then, we buy her materials and incorporate them in our designs.

Speaking of simplicity, I see that many of your clothing designs are based on what you call the square root. Is most Mexican clothing based on squares and rectangles?

Yes, it’s amazing that we have an endemic way of making clothing in Mexico. When in University, there is a beautiful project where you go to work for six months without payment, for the government or an NGO. You go to school, but in your free time, like in the evenings, you have to work in order to graduate. You get to choose what you like, so when I was 19 or 20, I decided to go to a museum that had a very important collection of folk costumes, and you could see how they were made. I wanted to reconstruct all the patterns because I already knew they were made from squares and rectangles. I wanted to see how the patterning persisted through the very South and very North of Mexico.

It does and it’s incredible. When the Spanish came, even the indigenous communities tried to copy the western fashion with its tailoring all very suited to the body. They made darts, pleats and folds, but always kept the squares and rectangles. They never cut it, even when they knew how to do it. Mexico is very unique in that way. Guatemala, for example, where they cut and make curves, is much more tailored.

What’s really intriguing to me is how they add tailoring but adhere to the squares. We have such an emphasis on clothing that enhances, that emphasizes the body—and provides less freedom of movement.

It’s a different kind of beauty. In the communities, beauty comes from the face, the hands, the feet, the hair. Here, you also see the textile that is being used, it’s like an open book. It speaks, for example, to you being a good embroiderer and that you are an amazing artisan. Beauty also comes from knowing that you or somebody in your family made the dress, and you’re very proud of that.

The future is handmade.

carlafernandez.com